I’m not precisely sure why, but it seems like everywhere I look lately there are the shadows of a past that doesn’t belong to me. On Monday night I went to Trampoline Hall, a beloved non-expert bar room lecture series in Toronto. The final speaker, actor and writer Vanessa Dunn, was very funny on the topic of her survivalist fantasies: “I’m a thirty-three year old woman,” she told her audience, “who always asks for a coke on the airplane, and I make sure I hold onto the can.” This because a quick weapon can be fashioned from ripping apart the aluminum, which would come in handy should a hijacking occur. While we were mostly laughing, amused by the absurdity of her paranoia, we in the crowd were also perched on a perilous edge: Dunn opened her talk by describing where she grew up, and when: Scarborough, in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Where Paul Bernado lived and killed.

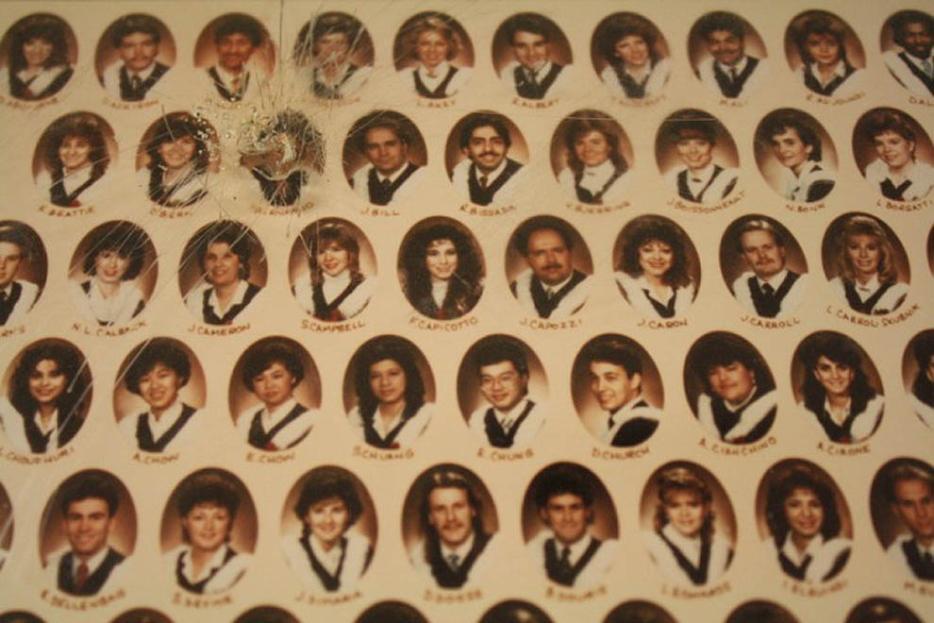

Even though I’m a bit too young (and originally from a city too far away) to have first-hand memories of what it was like to live during the time when Bernardo was serially raping women across the GTA, or the time shortly after when he and his wife, Karla Homolka, tortured and murdered three teenaged girls—Tammy Homolka, Leslie Mahaffy, and Kirsten French—there remains a lingering echo of that terror. The world may be a different place now, and Bernado is behind bars, but lately it seems like this two decades-old story is underwriting some aspect of the present.

Earlier this year, Stacey May Fowles wrote an essay for the National Post. The piece is woven together out of a few shimmering threads—on writing as an act of personal revelation, the recent rash of sexual assaults reported in Toronto, and the legacy of gendered terror that remains across the GTA, nearly 20 years after Bernardo was convicted for his crimes. The crux of Fowles’s essay was this: in July she was invited to work on a long-form non-fiction piece at the Banff Centre, after submitting a proposal in which she “pitched a memoir about growing up in Guildwood during the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, about coming of age in serial rapist and murderer Paul Bernardo’s hometown during his crimes as the Scarborough Rapist.” Once the project was underway, once editorial eyes were involved, giving feedback as Fowles tried to shape her narrative, the piece’s scope and focus shifted: “What was supposed to be a coldly reported, near-anthropological study of a specific community during a specific time, instead became a forced visceral purging of my own violation.”

The ethics and the boundaries of writing the horrible down are unclear—in both a personal and social context. When Lena Dunham cracked a tasteless public joke about dressing up as one of Bernardo and Homolka’s victims this past Halloween—another example of this story rippling onto the surface of today’s culture—there was a righteous backlash. When Lynn Crosbie published a novel imagining her own correspondence with Bernardo, in 1997, there was backlash. Profiled by Taddle Creek shortly after the controversial novel’s release, Crosbie described her intent in turning something so horrible into fiction: “…who is the truth teller? There is no one. Which led me to fiction. The only compelling truth claims could be offered by the girls who are dead, and they can’t offer them.”

Here’s the part where I tell you I haven’t read Paul’s Case. I have circled around the book. I took it out from my university’s library in 2007, but it sat unread on my desk for four weeks. I meant to bone up on the facts, to do the responsible thing and arm myself with something resembling the truth beforehand. The distance between 1987 (the year I was born, and the earliest known year of Bernado’s run as The Scarborough Rapist) and 2007 seemed so great then. But the facts were absolutely horrifying; I never managed to turn to the art that Crosbie had assembled out of and around them.

The morning after I heard Vanessa Dunn talk through her early fears, I happened to read a Q & A in Poetry with Michael Lista, who is presently at work on a book of poems called The Scarborough. He describes the work in progress as one “that isn’t about Canada’s most famous rapist and serial killer, Paul Bernardo.” Lista is interested in examining Bernardo’s particular monstrousness, and the poems, from what I understand, evoke and explore the mood and place of the time (Fowles on the same: “living under a pervasive and hysterical fear of violation”) within a formalized schema of cold dignity and even more chilling psychopathy: “You can hear the crimes, the perpetrators and the victims, but you can’t see them.” Frankly, I’m not sure I’ll be able to will myself to read this book, either. The anxious memories aren’t mine, but they still seem incredibly vivid and fresh.

Somehow 1987 doesn’t seem as far away any more, and so I’ve become warily but perversely interested in the reflection of the past on the present. What does it mean that Fowles, Dunn, and Lista are airing these ghosts? It’s been said that telling stories, that making art, is a way of forcing life into coherence—a means of taking control over the traumas that have damaged and reshaped a person, or a group. It’s a way of handling and owning the truths, such as they are.

But the thing is, I’m afraid of the truth, and how much I wish, in this instance, that history hadn’t bequeathed it to me, to us.