When the NDP dropped candidate Dayleen Van Ryswyk this week for comments she made online about French-Canadians, the entire affair had a familiar ring to it. As has happened so many times, someone said something stupid on the web, was called out for it, and was punished shortly thereafter.

Now, I don’t want to sound like a baying spectator at a Roman gladiator fight, but it can be almost enjoyable to witness this. Whether sportscaster Damian Goddard losing his job for his anti-gay marriage remarks made on Twitter, or Microsoft’s creative director being tossed for his dismissive reaction to gamer concerns, it’s satisfying to see terrible people being asked to wash the taste of foot out of their mouths with a nice cool glass of Oh-Hey-You’re-Fired Soda. If in the past, public figures could smile and make nice for the cameras and utter their ugly, prejudiced views in private, the immediacy and very public nature of social media is one more way in which the pernicious ideas that still poison our society can be subjected to more scorn.

But perhaps there’s also another side to the relentless and often unforgiving nature of this surveillance. The pace and often unfiltered nature of online communication means that moments for reflection, consideration and judgement are often lost. While hate-filled rants are still fair game, maybe more minor online gaffes, like a needlessly harsh word or a thoughtless joke, require a more open-minded approach—one that recognizes that mistakes, failures and errors are much easier to make in public now. And it’s also possible that, in order to think about this correctly, we also need to think slightly differently about what it means to be human.

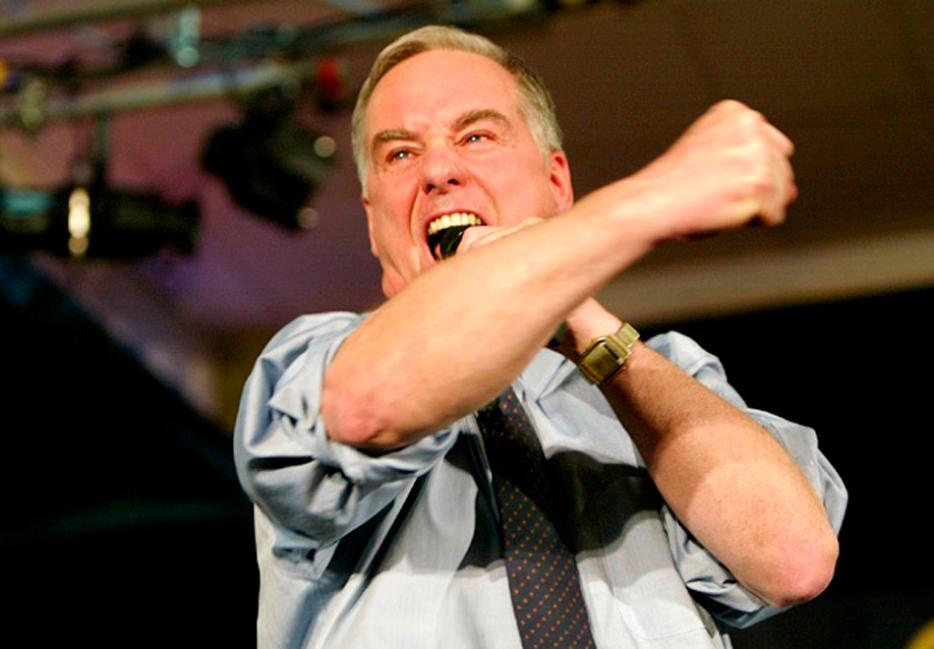

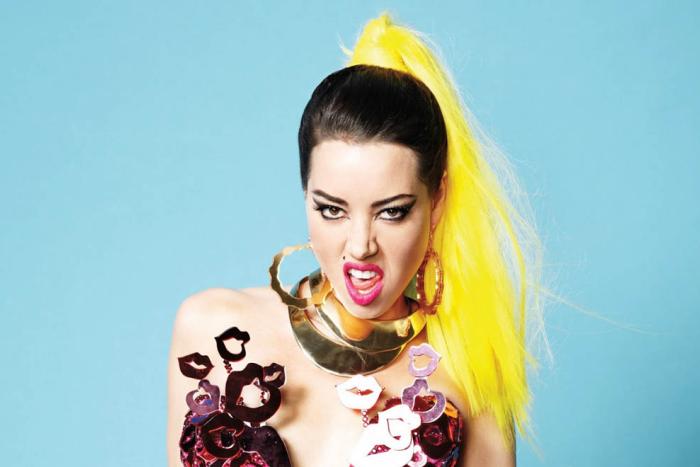

One of the things social media have done is massively expand the number of people who have a visible or public presence. In reaction, we’ve retreated to treating most people’s blunders like we do those of politicians: one screw up and you’re out. It’s like the Howard Dean Scream school of forgiveness—by which I mean that there is none. Maybe no example has recently made this more clear than the mess that erupted over Adria Richards, who tweeted a picture of two men she felt were making sexist comments. Not only did the men in question lose their jobs, but so did Richards. Though a very important conversation around sexism in tech occurred as a result, almost everyone agreed that the actual firings were probably an overreaction, a misguided quick fix to the sudden glare of public scrutiny.

It’s true that making a show of punishing people who express destructive ideas can have positive added effects. When comedian Michael Richards’ torched his career with a racist rant uploaded to YouTube, or Nir Rosen lost his job for a crass joke about Lara Logan’s sexual assault, they were public signals that such views are unacceptable. Despite the naive whining about “political correctness gone mad,” we still benefit from these very obvious reminders that hate and prejudice aren’t tolerated.

Still, what ideas about identity underpin the “gotcha” mentality that condemns people for one foul-up, no matter how awful? Usually, we tend to look at these moments as something being peeled back, or someone revealing their “true colours.” It’s a concept of the self that assumes a true, stable identity existing within us—one that, given the right mix of thoughtlessness (or alcohol) and access to Twitter, has a core that can inadvertently be revealed in a moment. Ah, we say, now we see who you really are—and we hate you for it.

But the same digital technology that enables these “revelations” also gives us another way to think about identity. Think of the many representations of yourself scattered over the web: Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, maybe a blog, and probably some comments here and there. Each of those expressions of self could be quite different: some very political, some very goofy, and maybe even some that represent some less savoury aspects of yourself. They might all be united by the body doing the typing, but even hunched over a keyboard, we are still large, and contain multitudes.

That self is a thing constantly in flux. Even a single Twitter feed can reveal someone simply grappling with the right way to interact with others, express thoughts, and be a good person. Maybe what we need in a time when media publicly express the way we put together our selves is a mentality that is more forgiving, more understanding, and more aware that “who we are” is never just one thing.

Because, beyond the simple fact that new social technology demands new social mores, there are also armies of people at Google and Facebook vying to tie down our identities to a single site, a single expression, a singular idea. That’s not what it means to be human, and especially when underpinned by a company’s desire for profit, it’s certainly not what it means to be free. People make mistakes. We change our minds, say awful things when we’re angry and then think to ourselves the next day, “Wait, that’s not really who I am.” Right now, there’s simply not enough room for the process of messing up and then putting ourselves back together to happen in public. But happen it will, which is why it’s time to rethink the popular idea of identity—and all cut each other a little more slack.