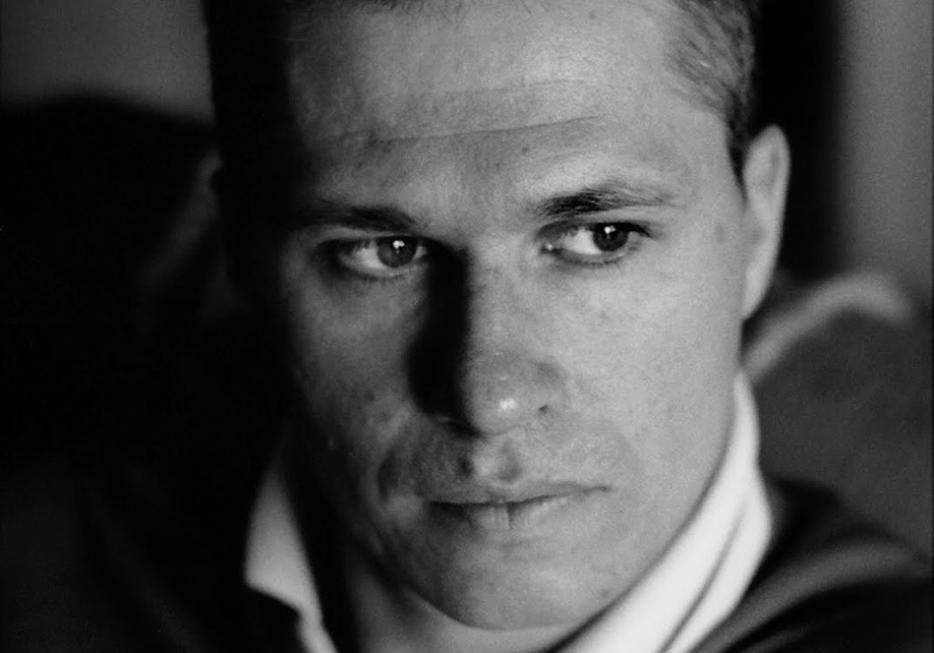

Aleksandar Hemon is a tall, athletic-looking man in a sea of nebbish Brooklynian tweed-and-sneakers types, although there are a fair number of women here to see him as well. He is bald and his glasses are wire-framed and small and he sat on the stool at McNally Jackson on Friday night like a man poised to make an escape. Opposite him was the novelist Colum McCann, who’d come to talk with Hemon about Hemon’s new book of “non-fiction” (that term is deliberate, more on it in a moment) The Book of My Lives. And as I was trying to get one of the last seats left I could hear people around me talking about just one particular part of Hemon’s work.

“That essay destroyed me.”

“It’s so sad, about his little girl...”

That essay, called “The Aquarium“ and detailing the death of less-than-two-year-old Isabel from a rare form of brain cancer, ran in the New Yorker last summer. A young friend of mine said to me after reading it he felt he “never wanted to love anything again.”

But this was not, it seems, the lesson Hemon took from it. He read from another essay, though, one about a professor he’d studied with at the University of Sarajevo, before the war, and before that professor became one of Radovan Karadzic’s yes-men.

This led nicely to McCann’s first question of his friend of “ten years” (“More,” interrupted Hemon) Hemon if he thought that literature could save people. The answer was an unequivocal no. “You can read all the Shakespeare you want, and listen to all the Beethoven, and still be a fascist,” Hemon said. But literature “provides a field in which people can have agency, which is not entirely political agency, but it is agency, the agency of connecting with other people, the agency of participating, even if imaginatively, in history.”

This is not the way novelists talk, typically, nowadays. I mean, of course you hear terms like “agency” tossed around, but in America, and Canada too, the agency novelists are currently interested in is typically exercised in a room with a closed door, and not one sought out for its bomb-shelter qualities, either. The social novel, Jonathan Franzen’s stabs at it notwithstanding, is not generally in vogue in white North American writing. Elements of war and strife always have to come from those who know the news from elsewhere, and listening to Hemon easily reel off his qualified belief in the power of books, it’s hard not to long for more of that here. More sense that there is a larger moral purpose available to us than the handwringing about the “totalizing” nature of moral purposes might suggest.

Still, the personal comes back after an abstract discussion about the distinctions between story, truth, and history. In Bosnian, apparently, there is no word for non-fiction, his translator’s been struggling with the question in terms of this book, because it’s all stories, in the framework over there. Hemon says he himself distinguishes between history as “what happened,” and literature as “what might have happened.”

It’s then that McCann, with the air of a man preparing to skip a rock across water, references “The Aquarium” as the most beautiful essay he’s read in “the last twenty-five years” or perhaps longer. Hemon tells the audience he wept as he wrote it, so much so that he found he could not write it in the places he usually wrote. He has friends in Chicago, he says, filmmakers, and they had a spare office at their studio. He would go there and write, them a screenplay, he his essay on grief, “and then we would have lunch.” (Hemon did not identify the filmmakers but one suspects they are Lana and Andy Wachowski, whom he profiled last fall for the New Yorker, when the film adaptation of Cloud Atlas was about to appear.)

“Were you saving your own life there?” McCann asked, the annoying pat-ness of the question covered by his amiable Dublin accent.

“No,” Hemon said, and mumbled a bit before he added, “The simple truth is that I couldn’t not do it, that I would be bailing on what I’d committed my life to, which is being a writer.” He didn’t want to “avoid difficult things, because if I do I’m a hack, and if I’m a hack I should have a lot more money.”

The audience laughs softly. I find myself thinking about agency again, the inadequate political-science sound of the word in cases like this, especially given that so much of “The Aquarium” is about helplessness:

One of the most despicable religious fallacies is that suffering is ennobling—that it is a step on the path to some kind of enlightenment or salvation. Isabel’s suffering and death did nothing for her, or us, or the world. We learned no lessons worth learning; we acquired no experience that could benefit anyone. And Isabel most certainly did not earn ascension to a better place, as there was no place better for her than at home with her family.

But Hemon referred, over and over that night, to his surviving daughter Ella, “the wisest person I know.” As detailed in “The Aquarium,” her way of processing what was happening to her small sister was the invention of an imaginary brother named Mingus. Mingus could have feelings she could not, and could also be subjected to the same health problems facing the baby. The fancy of the stories, as it were, served as a way for her process harsher realities. And, it seems, to help her parents to do so. I suppose, if someone had asked him, what he’d say is that the power of choosing not to “avoid difficult things,” to tell stories about them, feels like power to those who manage it.