Shelf Esteem is a weekly measure of the books on the shelves of writers, editors, and other word lovers, as told to Emily M. Keeler. This week’s shelves belong to Leslie Shimotakahara, a recovering academic and the author of The Reading List, an intimate memoir about the power of literature to reveal to ourselves who we are. Her shelves are shared with her partner, Chris, and take up the wall of their home office. The light diffuses perfectly through the space, and there is at least a small stack of books arranged on almost every surface in view.

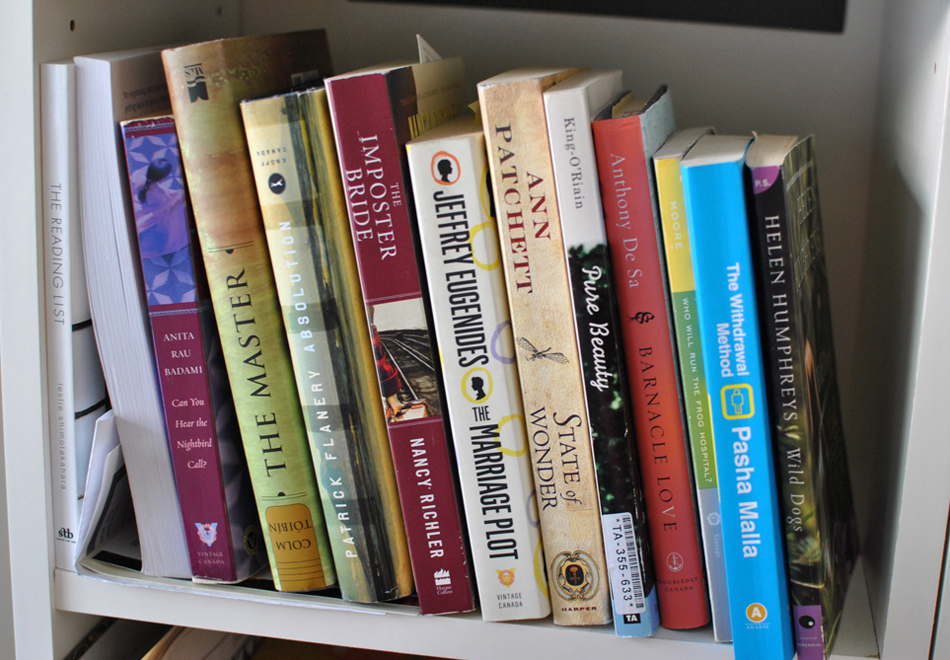

This is where I do my writing, and this is where most of our books are. They’re all jumbled together. We moved in together three years ago, and I’ve realized, just looking over my book collection, that a lot of my books, or books that I thought I had, are actually gone. I’ve had to unload them at various points along the way. I’ve moved so much over the past 10 years or so, from grad school, and I spent a year and a half in Berlin, and then there was research in Paris, and I taught in Halifax afterwards. Just at every stage, shipping books got more expensive. I had to let go of some. So I think a good portion of these are Chris’, and I’m like, Oh, where’s my copy of Absalom, Absalom!? There are certain books, like that one, that I’ve bought two or three times, and they just end up dog-eared and left in an apartment in Halifax or something.

Lucky Girls was, as I recall, a quite enjoyable collection of short stories. I think I bought it in Berlin, at a used bookstore. I think a lot of the stories take place in India. I read it during the period where I was in Berlin, falling out of love with my dissertation. I was supposed to be getting all of this work done, writing three chapters in the year that I was there—which might not sound like a lot, but they were academic articles. Instead, I ended up wandering the streets, going to galleries and plays, buying books at all of the English used bookstores, and becoming friends with a lot of the expats there. My mind rapidly began to wander from my dissertation to other creative writing projects that had been percolating in my head for a number of years. In a way, to be perfectly honest, looking back at that period, there’s a part of me that, in retrospect, kind of thinks, Oh, Leslie, you should really have just dropped out of grad school, thrown in the towel on your PhD and stayed in Berlin. There were a lot of people doing that in the mid-2000s—tons of Canadians, actually. It was such a cheap city to live in, and that alone makes it very suitable for living an artistic life. But I guess if I had done that, I wouldn’t have had my short-lived academic career, which gave me the material for my memoir.

Shelf Esteem appears every Tuesday.