Given the hoopla around the annual awarding of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, it’s worth remembering that the prize is still in its relative infancy. Not yet 20 years old, the award is widely considered Canada’s most prestigious prize, likely because of the $50 000 that comes with that sparkly tulip statuette. Unlike the older Governor General’s awards for drama, non-fiction, children’s literature, poetry, short stories, and novels, in both English and French language categories, there is but a single Giller. Only one. And it packs a punch.

As Mark Medley wrote, shortly before this year’s long list was released, “Despite the fact the coming months are filled with literary festivals, big books and other major prizes, the Giller shapes the narrative.” And the sales. It’s now a beloved literary legend that the small—heck, call it “artisanal”— Gaspereau Press couldn’t keep up with demand when their title, Johanna Skibsrud’s The Sentimentalists, took the prize in 2010. Gaspereau had to let go of the paperback rights to feed the masses, whose appetites are apparently stoked into overdrive by the phrase “Scotiabank Giller Prize Winner.” We readers have put a lot of pressure on this particular award, and publishers, other prizes, and the media have only encouraged us.

In the beginning, way back in 1994, it seemed like the award had to make up for lost time. The first five prizes went to Canadian literature’s marquee names: M.G. Vassanji’s The Book of Secrets, Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance, Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace, Mordecai Richler’s Barney’s Version, and Alice Munro’s The Love of a Good Woman—and each of these writers has since shown up on subsequent shortlists or juries. But not this year.

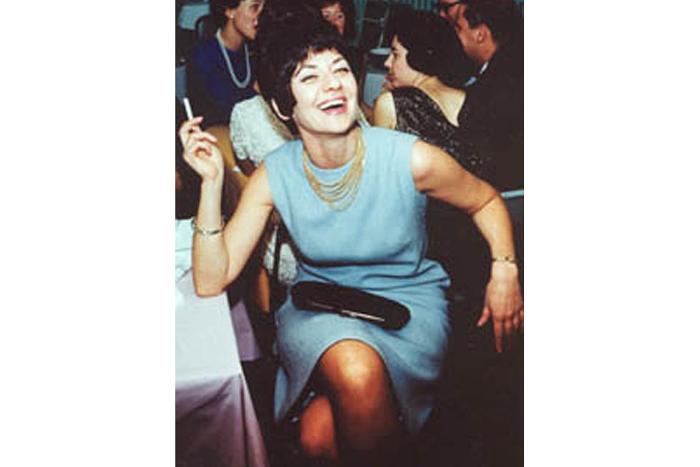

Even though heavyweights Vincent Lam, David Bergen and M.G. Vassanji all published high-profile new books in the past year, none made the longlist. The only Canadian writer on the jury, Anna Porter, is new to the prize as well, never having had one of her own books nominated. As it stands, the only person with any Giller experience this time around is Annabel Lyon (pictured above), for her feminist inquiry into the birth of western philosophy and Aristotelian logic, The Sweet Girl.

I do worry, though, about the lack of marquee names. Not because I’m particularity invested in the short history of Giller-Sanctioned CanLit, but because I wonder about the size of literature in the popular imagination. In 2010, there was noted celebration over the abundance of small press titles nominated, and last year Michael Ondaatje withdrew The Cat’s Table from the running for The Governor General's award, having already won the GG five times. Given the accolades that winner Esi Edugyan’s Half Blood Blues earned, including a nod from the Man Booker, it’s a safe bet that Ondaatje’s decision didn’t play a big role in the outcome, but I do wonder if perhaps the judges of both awards have taken Ondaatje’s hint.

But is it possible that, in trying to democratize sales in an ever struggling industry, Canada’s mightiest literary prize is spreading its influence too thin? Can it maintain its wide reach and its glitzy prestige, without relying on the well established credibility of CanLit’s historical top tier? Perhaps this is all just to say that the prize’s history is short, even though its reach is long. That said, we’re ready, I hope, for a fresh marquee. Even if it takes us the next 20 years to build it.

Correction: This article originally misstated that Ondaatje withdrew from the 2011 Giller Prize.