The truth is I always preferred Siskel.

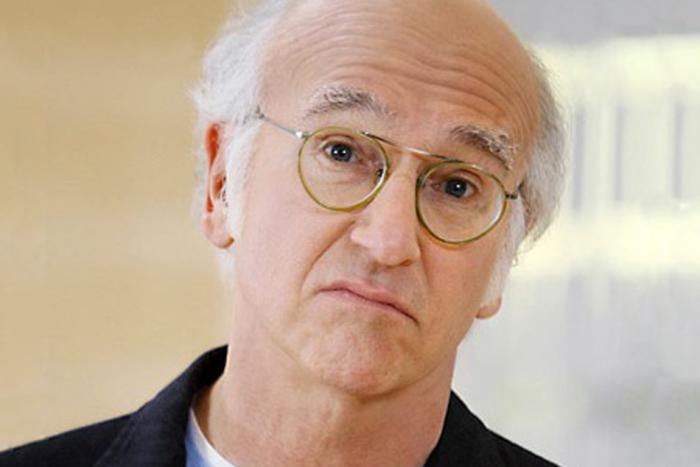

In him I thought I saw an intellectual, or at least what I imagined an intellectual might be. Bald, unconcerned with fashion and frustrated by the inferior world around him, he struck me as the sort of guy who played chess quickly and understood the complex mathematics of jazz. To me, he looked haunted by the fact that although he believed he was smarter than you, he knew that you’d always be happier and more at ease than he was.

And then there was Roger Ebert, his populist antithesis. Overindulged and overfed, he was the sort of guy who would wait in a three-hour lineup to go on a ride at Disney and, later, just love it when the twister spun a cow into the air of some Helen Hunt flick. He was too easily pleased, a creature that responded reflexively rather than analytically, and I decided that he didn’t have the intellectual capacity to see that that “serious” was way more important than “fun.”

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

The truth was that I actually knew nothing about the men. I’d never read a word either had written and my understanding of them was based exclusively on the hyped-up banter I’d seen them perform on At The Movies. They were nothing more than projections of what I needed them to be, blunt, oppositional symbols of tribal affiliation. Ebert was the suburban optimist, Siskel the downtown cynic.

And this is the way that I lived my twenties, dividing things into categories that were either good or bad. Life was simple, young and unhappy. And then I got cancer and things kind of tilted. I stopped caring about categories, and as tiresome as it might sound, I believe I grew up.

I didn’t think much about Siskel or Ebert in the ensuing years. The Internet had become the primary delivery system of my life, and the two men fogged into distant memories, like old baseball players I used to follow.

And then in 1998 Gene Siskel got cancer. He took a leave of absence to have brain surgery and then, eager to return to his show and life, came back to At The Movies to review films and spar with Ebert, only via telephone instead of in person. It was too soon and it was clear that he was greatly diminished. His disembodied voice was thick, slow and uncertain, and a boxed photograph of him hovered in the corner of the TV screen as if a ghostly foreshadowing. He could no longer keep pace intellectually and his presence made for very difficult, even cruel TV.

In a year he was dead.

Ebert continued along with a variety of co-hosts, and in each formulation it was clear to anybody watching that he was and always had been, the presiding spirit of the show. Maybe he’d changed (I know I had) but I saw more in him than I had before.

And then in 2006, Ebert got cancer.

It was brutal. He lost his ability to speak, eat or drink and underwent multiple, complicated surgeries that left him only a vague suggestion of the physical being he had once been. However, his voice grew stronger in the midst of this, not weaker. He became ever-present through social media, revealing the personal and spontaneous in an endlessly winding conversation that granted us access to the interior man and not just the projection we had seen on TV.

There was greater generosity and intellectual breadth to him than I previously thought. Complex, flawed and empathetic, he was whip smart and had an easy talent that he was only too happy to share. What I had aspired to when I was younger—as I imagined embodied in the Yale-educated Gene Siskel—was an intellectualism that was so keen that it practically existed outside of the body. But this was a failure of heart rather than a victory of mind, and in the last oddly radiant years of Ebert’s life, when he practically did exist exterior to his body, I saw in him a beautiful kind of coherence. In spite of the ruination of his physical form, he was bright, happy and useful. Occupying more of the world in illness than he had before in health, light poured forth from him until the very end.