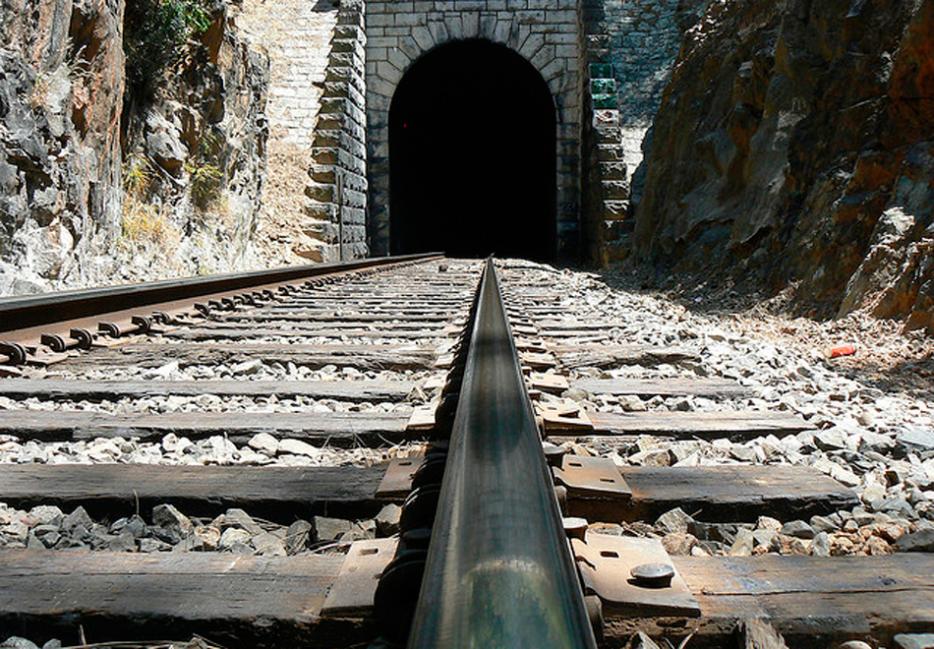

Imagine that you’re standing on a footbridge overlooking a train track. Beneath you, a small train is hurtling towards five unsuspecting people. The only way to save them is if a heavy object blocks the train’s path. As luck would have it, you are standing next to an extremely fat man. Do you push the man, killing him, but saving the other five? Or do you do nothing, spare the overweight innocent, but let the five others get mangled by the oncoming locomotive?

The dilemma is a variation of the “trolley problem,” a classic ethics thought experiment that has been used for decades, with various tweaks. What’s going on in your brain when you make this decision? You’re relying on some sort of moral code, but how exactly are you weighing your options?

In a study published last month in PLOS ONE, Albert Costa of the Pompeu Fabra University and University of Chicago psychologist Boaz Keysar argue that your response to these kinds of moral dilemmas may not be based on well-considered logic or deeply held values, but could be influenced by something as seemingly frivolous as whether or not you’re confronting the problem in a foreign language.

In one experiment, the researchers found a variety of people who had learned a foreign language late in life—native English speakers learning Spanish in the US, Koreans learning English, French or Spanish people learning Hebrew in Israel. They were all non-native speakers who were still able to speak the language well enough to understand the experiment. The test subjects were then divided in two and presented with the trolley problem, half in their native tongue and half in a foreign language.

The researchers found a startling difference between the two groups. While just 20 percent of people considering the dilemma in their mother tongue decided to push the man, 33 percent of those who read it in their second language opted to shoved him. In a follow-up experiment with 725 test subjects, the results were even more striking: this time only 18 percent of test subjects chose to push the man while reading in their native language, while a full 44 percent of the foreign language group decided to.

The results, according to the researchers, are due to the way that emotion is carried in different languages. When we need to make a moral choice, there are two different, sometimes conflicting forces in our heads: an automatic, emotional reaction to the situation, and a rational, carefully considered response. In general, this intuitive, emotional reaction makes decisions based on “the essential rights of a person,” while the rational, cold-hearted force takes a more utilitarian approach, favouring the greater good regardless of the consequences for any single individual.

According to past research, dealing with a situation through a second-language reduces emotionality. There have been studies in which researchers have found that people’s skin conductance is lower responding to emotional phrases in a second language rather than in a native tongue. Keysar, the co-author of this study, has done previous experiments showing that working in a foreign language made decision-making more rational. Assessing a situation in a foreign language, it seems, creates emotional distance; the dilemma becomes less fraught, more abstract and intellectual. Separating yourself psychologically from the visceral idea of pushing someone to his death, you think more clearly about the utilitarian consequences: sacrificing one life to save five. In their second experiment, the researchers found that test subjects who showed more proficiency in their foreign language were more likely to mirror the choices made by the native-language group. As people got more comfortable in their second language, the choices they made became more emotional, less utilitarian.

These types of studies are fascinating, and vaguely upsetting, because they begin to reveal some of the mechanics behind our decision-making. We may not know exactly what controls our moral compass, but we like to think it’s something important—the product of deep thought, learned behaviour ingrained in childhood, or perhaps a sense of morality deeply embedded within the human genetic code, the endpoint of an ancient evolutionary process. We like to believe that the way we respond to a moral dilemma, our sense of “right” and “wrong,” is a consistent part of our character. The reality—that our moral code might be so unmoored that a simple change in language could bump it off course—is a little unnerving. Especially for the guy next to you on the bridge.