In his acclaimed biographies of John Cheever, Richard Yates and Charles Jackson, Blake Bailey planted his flag in some very specific literary territory: the messy, furtive life of the alcoholic, suburban writer. His new memoir, The Splendid Things We Planned, reveals just how close to his heart the subject is.

The book is nominally a chronicle of Bailey’s complicated relationship with his older brother, Scott, whose drug and alcohol addictions are just the tip of an extremely self-destructive iceberg. But it’s also, perhaps more significantly, a pitiless self-portrait. For an uncomfortably long portion of their youth, the Bailey brothers of Oklahoma City were not so different, at least in affect—where Scott was wayward and volatile, Blake was feckless and dissolute. Equally arrogant and vain, they also shared a fondness for blackout drinking and strained, often heartbreaking, relations with their parents. “You’re gonna be just like me,” Scott damns Blake early in the book. “You’re gonna be worse.” If Bailey has made a specialty of anatomizing men who lead troubled double lives, here he depicts a pair of man-boys trapped in twinned despair. Despite many moments of dark, off-kilter comedy, it’s a harrowing, exhausting and unsettlingly candid account.

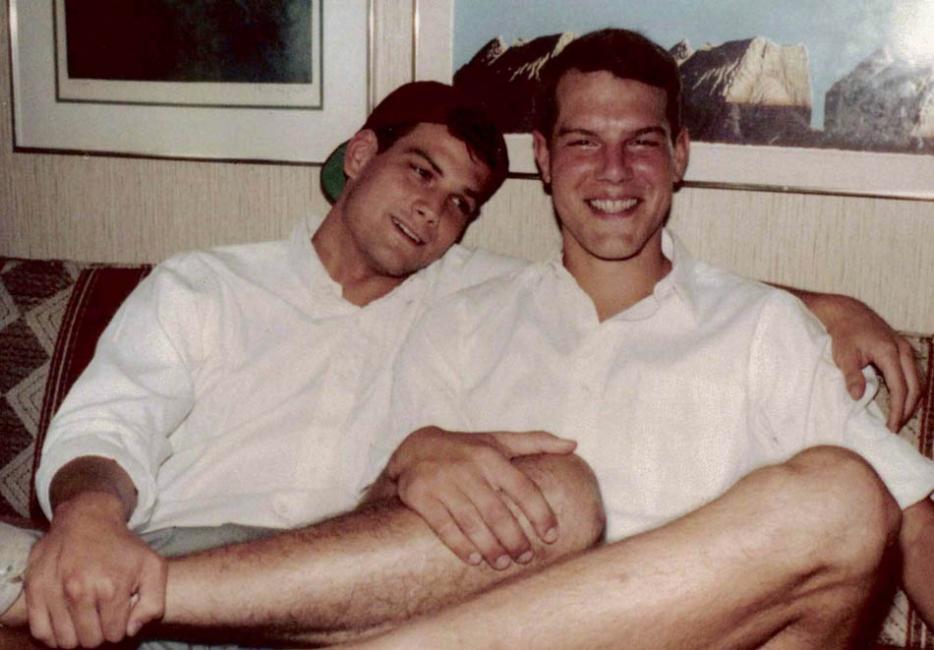

Before the drugs and alcohol become truly deranging and dangerous, Scott is a golden boy, handsome and charismatic, even if slightly odd. Blake meanwhile lurks uncomfortably in his shadow, his own vices and self-loathing a kind of sad, slavish imitation.

Scott Bailey was a problem from the beginning. In 1960, the year that Scott was born, Burck Bailey was an Oklahoma-born, NYU law student living in Greenwich Village with his bohemian, 21-year-old German immigrant wife, Marlies. Tortured by Scott’s incessant wailing, the couple head to the roof of their dorm room and contemplate a horrific choice—should they fling themselves to the street below, or the baby? A couple pages later, Bailey recounts another awful moment: suffering from debilitating postpartum depression and with Burck in the hospital with a bleeding ulcer, Marlies tries to stop Scott’s screaming by smothering him with a pillow. He, of course survives— “Even then, Scott had a knack for self-preservation in spite of everything,” Bailey writes.

Over the next 250-odd pages, “everything” will include Burck and Marlies’ divorce, his own addiction to booze, heroin and crack, an unbelievable number of car crashes and arrests, several failed friendships, romances, and careers, and stints in the military, jail, and rehab. Most of this takes place in Oklahoma City—“hardly a marvel of cosmopolitanism,” in Bailey’s estimation—where the family moves so Burck can take a job as assistant Attorney General, and where Blake is born, three years after Scott.

Before the drugs and alcohol become truly deranging and dangerous, Scott is a golden boy, handsome and charismatic, even if slightly odd. Blake meanwhile lurks uncomfortably in his shadow, his own vices and self-loathing a kind of sad, slavish imitation. Sibling rivalry has rarely been rendered so acutely. When Scott takes the lead in the high school play, Blake picks up a bit part. When Scott writes a story that’s a terrible Salinger knock-off, Blake does the same. When Scott wrecks his Porsche, Blake totals his Jetta. When Scott’s antics anger his father, Blake moans that Scott’s still the more beloved son.

But as Scott grows increasingly alien and his life more lurid, Blake yearns for normalcy: genuine love, a respectable career, literary fame. He might read and admire A Fan’s Notes—Frederick Exley’s classic ficto-memoir of alcoholic self-loathing—but, at bottom, he doesn’t want to be Exley. Escaping Scott’s shadow, however, is hardly easy. “When a child is young,” Burck explains to Blake, “you can catch him if he falls. Then he gets a little older and falls from a higher place. Maybe you can still catch him. But finally he’s a full-grown adult and falls off the top of a building—then you have to decide: either get out of the way or be crushed.”

Bailey, who is currently working on the first authorized biography of Philip Roth, spoke to Hazlitt on the phone from his home in Virginia.

--

I don’t mean this pejoratively, but this is an exhausting book to read. I can’t imagine how exhausting it was to re-live these events while writing it—let alone experience them the first time around.

What made it possible to write this book, especially the more ghastly parts, was finding the humour in it. And that was actually fairly easy and curative given that that was precisely the sensibility that appealed to my brother. Which means that it was precisely the sensibility that appealed to my brother and me.

You worked on it for eleven years.

I had just finished my Yates biography and had no idea what I was going to do next. My brother was still alive at the time. But not for long, and I knew that. And I was already sort of grieving what was about to happen and I wanted to sort that out.

But you were obviously working on both the John Cheever and Charles Jackson books at the same time.

Yeah, those were bulky distractions [laughs].

How did that work? Was it difficult to switch gears?

No. Basically, I finished a whole draft between Yates and Cheever. And then, when I was done with one phase of Cheever, I went back and revised that draft. But it was always betwixt and between. I never worked on any of it simultaneously. And it’s a very different kind of writing in many ways. I had tried for many years to be a fiction writer and I think I became a good prose stylist and got a sense of narrative pace and structure. And that stands me in good stead as a biographer. But writing narrative was something I had worked on however successfully or not successfully for many years. It wasn’t wholly unnatural to me.

Did you try to explore this material in fiction before?

Yes. As a matter of fact, the first scene I wrote is the most dialogue-heavy scene in the book. It’s where my brother and I get in a fight in a parking lot in a restaurant—it’s in the middle of the book—and the reason I allowed myself the liberty of all that dialogue, which is usually kind of cheesy because no one really remembers what was said, was that it may have been the first fiction I ever attempted. Of course it was in much more apprentice form when I first wrote it but I wrote it very shortly after it had actually happened.

What did you find you could do in non-fiction or memoir that you couldn’t do in that story?

Let’s put it this way: by the time I was ready to write this memoir, I was done as a fiction writer. I had given that particular ambition up. This was just the way I was going to do it. I didn’t know if it was going to be more effective or not, though I think it’s inherently more effective in that you’re writing about something that actually happened—and the reader knows that.

Does fiction still nag at you?

It does, yeah. My friend, Michael Ruhlman, who’s a well-known food writer and who’s in the book— he’s the guy I’m living with in New York when I brought the pregnant hooker home—wrote this nice piece on his blog about my Cheever biography. He said, of course, when we were in New York we both aspired to write novels. And to start out wanting to write fiction and end up a literary biographer is like the actor setting out to be the next Olivier and ending up like Wayne Rogers playing Trapper John on M*A*S*H.

You obviously interviewed friends and family when you were writing the book, but were there primary source documents that you used to? Did you keep a diary during those years or anything like that?

Not much in the way of primary sources. My mother wrote me a series of long memos. For example, about her drunk driving arrest. When I am not able to report a scene firsthand in the book, I make allowance for that. For example, I say, “I may be misremembering details, this is something my father told me, etc.” But my mother wanted me to get that stuff right. But what was funny about that was that her memos correcting my factual accuracy generally made things seem even more damning than they had been previously. She was a great help. I did consult photo albums a lot. My mother has an exhaustive set of those. And clippings like my grandfather’s obituary in the Vinita Daily Journal, that sort of thing. I couldn’t consult my father because I don’t speak to the man anymore. That’s why I say in the text, I might be misremembering things.

You don’t speak to your father at all now?

I do not.

I thought that there might have been a rapprochement towards the end of the book.

My eventual falling out with my father, which I hint at very elliptically, had nothing immediately to do with the story. And I was very selective about what I deemed pertinent.

You say in the book that, in many ways, your wife, Mary, saved you.

Yeah, the whole story is about how two brothers, who were in many ways quite similar, took very different paths in life. I only have two explanations for that really. One is that I found a good woman. And two, I just never had the relentless self-destructive impulse that my brother had.

Do you think if Scott had met someone comparable to your wife he could have been similarly saved?

If he had met someone comparable to my wife, that person would have had the sense to run the fuck away as fast as possible [laughs]. As I told my mother repeatedly throughout the book and in life as well, people like Scott’s girlfriend, Maryam, as well as his good friends, all turned out to be every bit as fucking crazy as he was. So, the short answer is no.

It’s not a very diagnostic book. Was it intentional that you don’t spend a lot of time speculating about what exactly is wrong with Scott?

Yeah, there is that part where Dr. Hauber, the shrink, says that he’s a paranoid schizophrenic. And I dismiss that with one parenthetical phrase: wrongly, I think. I elaborated on that in an earlier draft and it ended up on the cutting room floor. The gist of the elaboration is this: my wife is a psychologist, though I don’t need her to tell me this, but schizophrenics have serious psychotic hallucinations. They think they have transistors in their heads with the government telling them they’re the messiah or whatever. That was never Scott. Scott had the sort of delusions through which any addict fits himself into the world.

Is there a spectrum for schizophrenia as there is for autism? Could he have been slightly schizophrenic?

I think there’s a spectrum for everything. And I have a great deal of skepticism for any pat psychoanalytical categories of any sort. I don’t think anyone is entirely one thing or another. Scott certainly wasn’t, though he had some serious mental health issues. Without DSM IV-ing my brother, I think a lot of his problems go back to early childhood. After he was born, my mother was truly, almost psychotically, afflicted with post-partum depression. And that was not good. And he was a very strange, difficult, non-attaching child.

When you were writing the book, who was your loyalty to? To the reader, who wants a really great story? To Scott? To yourself? To some kind of abstract truth?

I don’t consider questions of loyalty when I write. I try to satisfy myself aesthetically.

There are so many competing truths, I guess.

If that’s going to stymie you, then you have to find a different genre to write in.

Maybe not stymie so much, but does it spur you in one direction or another?

I know what my own point-of-view is. You know, there’s a Hemingway adage for every department of life, from making a good daiquiri to you name it, but the one that stood me in good stead is: don’t describe the way you were supposed to feel, describe the way you really felt. So for example, when I heard of Scott’s suicide, I felt nothing, or something very close to nothing, but relief. And the grief that came unpredictably, and comes unpredictably to this day, is an entirely separate phenomenon. I just tried to get things right, and right even when they were profoundly counter-intuitive.

Not to overstate things too much, but you are the foremost literary biographer of our day and the Blake Bailey in the book in such a loser. That heroic transformation isn’t really in the book very much. Was that again a conscious choice of selection?

That would have been really egregious self-aggrandizement. Anyone can look at the book flap and see that I’ve written these other books, well, good for him. I let the reader know that I got my shit together and that’s all they really need to know.

Frederick Exley comes up a couple times in the book. I know Jonathan Yardley’s written a biography of him, but is he someone you’ve ever considered writing a book about?

In a word, yes. Because Yardley’s book stinks—he interviewed only a handful of people and not very in-depth. It does not do justice to what is, for my money, an endlessly fascinating subject. I mean, you want someone who was a colossal fuck-up? The real mystery is how did Fred Exley write that book [A Fan’s Notes]?

So, you might someday?

Dude, I’ve got Philip Roth on my hands! For years and years. Forget about it, I can’t think ahead at this point.

Speaking of Roth, how different is it to write a biography of someone who’s still alive?

There was a New York Times piece in 2007 by Rachel Donadio on whether it was wise to write about living subjects. And it was primarily about Ross Miller’s arrangement with Philip Roth. The person they primarily interviewed for that piece to address the other perspective—that, no, you should never write about living subjects—was me [laughs]. It is hard enough to deal with a subject’s estate, their family, their spouses—in Cheever’s case, that was wonderful—than to have the actual person looking over your shoulder. All that said, so far it has been almost miraculously easy going.

When people nervously call Philip to ask if they should speak to me, or whether they should give me letters that he’s written them, he abides by our written agreement, and he says, you tell him whatever you feel like telling him, or give him whatever you have. And in terms of my relationship with Philip, it could not be more jolly. He’s a wonderful, charming person.

When you were writing this book, were there any other memoirs that were particularly inspiring or you looked to as models?

As models? Geez Louise, nah, not really.

Are you fan of the genre per se?

You know, I like the usual ones. I like Frank Conroy’s Stop-Time a lot. J.R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself. I like Brooke Hayward’s Haywire. It’s a terrific book; I wish more people knew about it. And Darcy O’Brien’s A Way of Life, Like Any Other is putatively a novel but it’s really a memoir about growing up with two washed up Golden Age Hollywood actor parents. And it’s wonderful. That really captures the tone and sensibility of how I aspire to write.

What does writing a memoir give you, as a writer or thinker, that writing a biography doesn’t?

The downside is learning all over again how brutally unglamorous a biographer’s life is. Some of my closest friends have read and enjoyed this memoir who would never dream of going beyond chapter one in one of my cinderblock literary biographies. Which is a shame. I hope it doesn’t seem too smug to say that I’m immensely proud of those biographies. But they just don’t have the same readership a more slender volume does. I’m very pleased with the critical reception for this book. I think it’s selling okay, better than expected. The main thing is that people I know are reading it and that has not always been the case. They’re just not literary people.

How difficult has it been for you to have this in the world?

It’s not been difficult at all. Unless my stepmother sues me [laughs]. No, let me answer that with the gravitas it deserves. Six or seven of my closest friends in the world, who I am very much in touch with to this day, are in Oklahoma and grew up with me, and I would not discuss this stuff with them. It was just too painful and humiliating. And now I can discuss it. Or rather I don’t have to discuss it because I put it in a book and they can read about it. That’s been very important to me. It’s truly a load off my mind.