Until mid-April I had never read or wanted to read James Salter. In my head, he belonged to a class of old, manly American writers I knew to respect, but also to hate: Norman Mailer, of course; John Updike; Philip Roth. Someone I used to admire told me nobody writes sex like Roth, and after reading four pages of American Pastoral, I fucking hope that's true.

One day, a Saturday, I sat under the Williamsburg Bridge watching a guy play tennis and not talk to me. We had been friends for four months, the latter 10 weeks of which we’d spent having sex less and less frequently, texting more and more. He invited me because he liked to have one or more girls watch him do things, and although when I looked at him I saw a great friend and possibly a genius, he looked at me and saw a girl. Yet, I stayed. I liked watching the things he did: Sports, karaoke, the entire dance routine to “Dirty Diana.” I wanted to watch him have sex with someone else, but when I said so he seemed not to believe me. It was that kind of relationship. It was also the kind of relationship in which he would never, not once, have watched me do anything. He didn’t read things I wrote, which I felt was fine, a relief. But then he didn't read things I read, and that was not fine.

His tennis partner was older and had a wife and a kid. I played games with the kid that seemed expressly designed to bruise me, usually with yellow balls but also with shoes, a wallet, a small fist, and with the wife I talked about books. She seemed to like me because I was smarter than most girls who would spend a whole afternoon watching a guy play tennis, something I guiltlessly let her believe. I was reading Lorrie Moore. She was reading Salter. When I told her I’d never read James Salter, she looked like she’d found her purpose in life. She sat up straight. “James Salter is one of our favourite writers,” she said. I liked her anyway.

After the tennis game, the guy and I walked to American Apparel, where he did not buy anything, and to a juice bar in the East Village, where he was dissatisfied with his order. Two of his friends met him outside. I smoked. The seconds went by like minutes, and then he had to be alone. I turned and left without saying goodbye or realizing I wasn’t saying goodbye, just—it was a reflex, and in 10 more seconds he texted that it was rude of me to do so, that surely I hadn’t meant to be so rude, and then again maybe he was just sensitive, but also, I was rude. I thought about never texting back. Then I called him.

What I didn’t say on the phone was that it takes a particular kind of ego to make someone feel unwanted, then blame her for walking away. Well, what was the point. This wasn’t the first time I had loved somebody who would never know how to be my lover, not really, and what difference would come of teaching him, in the spring, just so I could leave in the summer.

I was early to meet Durga. I felt light and sick, like the light before a tornado. It didn’t rain. I found an old bookstore wherein the first Salter I saw was A Sport and a Pastime, in paperback, with the girl in her ochre stockings, the moss-coloured room, and I bought it. That night I went to a dinner party and fought badly with a very good friend. Dinner parties often make me feel murderous, but that night, I think, it was the other way around. I stormed out and went to sleep, but couldn’t, and so from six a.m. ’til the sky turned blue I read.

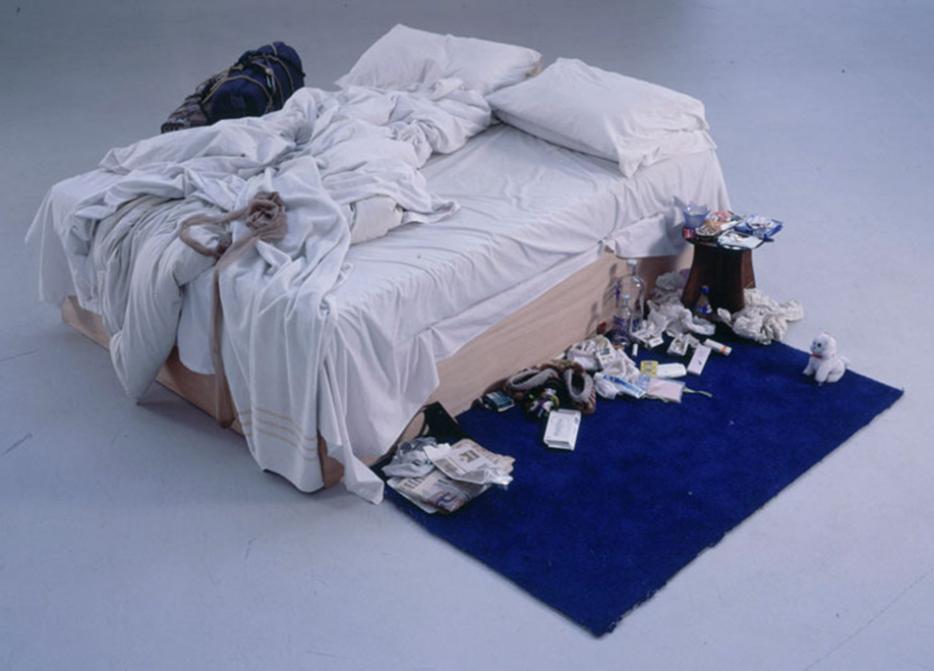

Blue is the thingness of the novel. Was I reading it because I was blue, or was I blue because I was reading it? This is the wonder of a book you love, that you can't know; it’s like a horoscope. It is true, but you don't know whether it would be true had you not read it. Had you not been looking for the thing. In mid-April, on a Sunday, A Sport and a Pastime made clear and true and blue as blue water my desire. I didn’t want to be longing where I wasn’t gonna stay. I wanted to be desirous and whole, like the book, which left its lovers with no choices, and so, although in the stream of three hours I stopped only to cry, at the end I was completely un-depressed. There's no ecstasy like this kind of reading. Suddenly I had loved this fucking Salter book since I was old enough to be a virgin. Less important was the idea that I should give it to this guy, who was like, so busy and so tired all the time, so that before I walked away for good, for better, I would have let him know—if he wanted to know—what I had wanted from sex: Not another game, but a sport.

I had already begun underlining sentences I felt the most and the sentences I thought the best, and they were the same sentences and I was thinking of him.

Sentences like: “With a touch like flowers, she is gently tracing the base of his cock, driven by now all the way into her, touching his balls, and beginning to writhe slowly beneath him in a sort of obedient rebellion while in his own dream he rises a little and defines the moist rim of her cunt with his finger, and as he does, he comes like a bull.” And: “These atrocities induce them towards love.” And: “Nothing.”

These and 100 or 120 more I underlined, and I underlined every instance, no matter how pale, of “blue.”

The narrator in A Sport and a Pastime is a photographer, 34, living in “green bourgeoise France.” His subject is the beautiful, shiftless Philip Dean, 20 or 24, I forget, but anyway being 20 in 1967 is like being 24 now. His other subject is the girl, Anne-Marie Costellat. Salter’s style is consistently described as imagistic, to which I’d add “similistic,” the book’s best simile—on a train ride, “it’s as if a huge deck of images is being shuffled”—being also its best descriptor. It’s so good. When I read it I put my hand over my mouth. And yet the feeling is not of a still image, a photograph, but of a painting of a photograph, the way paintings used to be done, when reality was more truthful than we know it is now.

My own reality being generally a little suspect, I wondered again if I only saw so much blue because I was looking for it. The other day I re-read, played paint by numbers. And I was right. Nobody notes more colours than Salter’s narrator. On the first page alone, we have the dark green of the coach seats, a grape-coloured birthmark, and then the blues of a suit, the blue jacket and blue pants, “blues that do not match.” After black and white and dark and pale—almost nothing is grey in A Sport; it’s all soft, flashing chiaroscuro—the colour of most things is blue. Carpet, the car Dean drives, and the sky, of course, but also things that don’t have to have a colour, like cities. Light is blue. Flesh is blue. After blue there’s green, seen often next to black; there’s more gold than silver, more red than pink; yellow comes sometimes unexpected. It’s the palette of a forested road trip, the destination a lake. You swim in this thing. I’d add another word, if I could make one up: Surfascistic. It will not let you drown.

Maggie Nelson made a whole book, of something like poetry, about blue. Of course the blue is about other things: Sex, love, lessening.

Nelson: “Goethe describes blue as a lively colour, but one devoid of gladness. ‘It may be said to disturb rather than enliven.’ Is to be in love with blue, then, to be in love with a disturbance? Or is the love itself the disturbance? And what kind of madness is it anyway, to be in love with something constitutionally incapable of loving you back?”

But for years I’d been used to madness and to a state of longing and could more easily reconcile that than straight desire. I’d been infatuated with the bluest-eyed boys. Finally, one of them had been good, very good, and I’d quit him after less than a year because I didn’t want—I didn’t know. In the summer we drove. We lived, like Salter’s lovers, “in Levi's and sunlight,” and lived apart: He in Toronto, me in New York. Like Salter’s lovers, too, we’d never make it all the way to living here, in America, together. I guess that’s what I knew. I would not let a year of happiness turn to one of ash. And I was heartbroken, but for that I found I was prepared. I was less prepared to be in love again. I was and am in New York and what did Vivian Gornick say? I’d rather leave a man than leave New York. No, it wasn’t Gornick who said that, although I’m sure she would mean it. Susan Miller said that. Queen of horoscopes, she’d understand about the Salter. In any case: I was ready for heartbreaks, one after the other, crystals slipping off a string. I wasn't ready to be held tight. I didn't think.

When everything in A Sport I loved most was underlined, and when I could breathe again and get up, I put on a cheap black slip and Converse and a varsity jacket and Nancy Sinatra in my headphones and went to this guy’s. I didn't text him. It was like elementary school. I just rang the doorbell and when he didn’t answer I rang again and then I snuck in behind someone with a dog and left the book at his door. When I was at the end of the street, he texted. I went back. I was happy, wearing less makeup than usual, a little tanned.

“I’m sorry I’m such a freak,” I said.

He said I wasn’t. He glanced at the inscription, which told him, precisely, nothing but what day it was. Then he held me like he knew I would leave, but I didn’t want to, and I wasn’t sure what to do about it except kiss his neck ‘til there was nothing else we could.

Vivian Gornick reviewed Salter’s latest, All That Is, in Bookforum. She spent much of her essay talking about A Sport and the sex in it, calling it “mythic” in a way that implies not “unreal,” but “untrue.” Which is wrong. I’m inclined to side with smart, disaffected bitches versus old established men, but I know from many-splendoured experience that Salter isn’t making this shit up. Gornick notes that Dean is always entering Anne-Marie from behind. First, that doesn't mean fuck-all about a relationship between two people. Secondly, it’s incorrect. The lovers fuck in every single, every last position. Some are less picturesque. Sometimes her breath rots, or his middle softens, or she is distant, or he’s repulsed, but always they find each other naked. A Sport has that Fitzgeraldian diamond quality, but in sum it’s not nearly as clean or improbably beautiful as Gornick, and other critics, think. It’s only that if you describe light as well as Salter does, you can also describe dust and it’ll glitter.

After it I took a picture of him in the cream-curtained sun, with a cigarette, more naked because he wasn’t wearing a hat and he always wears a hat than because he wasn’t clothed. It was a picture of a lover, but not mine, and I think it made him laugh but not out loud. I had never taken a photograph of him naked. I would never take one again; I knew that, or I wouldn’t have taken it at all.

“I am creating him out of my own inadequacies, you must remember that,” says Salter’s narrator, to whom Dean is as mythic and infuriating as Angela is to Clarice Lispector’s male alter ego in her last, consummate novel, A Breath of Life. “I am afraid of him, of all men who are successful in love.”

I did remember that, later, when I saw how this guy looked at me from the photo. It was unlike how he had looked at me in life, and not at all unlike how he looked to other girls. Well, anyway: Photographs become images, and images get discoloured in time.

Two weeks later I walked away, and in two more weeks I would spend 20 minutes or more telling this guy who wanted me to watch him do things why I was his friend, but we could not be lovers, but I loved him, expecting not to be understood. Why weren’t there synonyms. It was impossible. I just wanted to say finish that fucking novel. If there are no synonyms for love, that’s why Salter has similes. Plus, I know you read the inscription and I know the postscript said I’m sorry, I should have done this in pencil, and I should have, but also you should just finish the book. One, it’s not that long. Two, you would be sad, and being sad is more accurate than being sorry. It really is.