Is the e-reader already dead? It seems like a strangely premature question. Only a short while ago, a Kindle or Kobo was the very model of shiny new technology. But after an incredible uptake among readers—that saw a million units sold in 2008 grow to nearly 28 million by 2011—according to a recent Pew Report study, growth of e-reader sales have already started to slow, and it’s likely that devices like the iPad are to blame.

Predictions are that the trend will continue in that direction, dropping to only 7 million units a year by 2016. It seems the market has spoken: when it comes to sitting down and reading an e-book, for many, the multifunctional, glowing tablet is the device of choice. And it was that fact that recently prompted a fascinating conversation between techno-skeptic writer Nicholas Carr and cyber-utopian academic Clay Shirky, each of whom had radically different take on the future not simply of the e-reader, but the book itself.

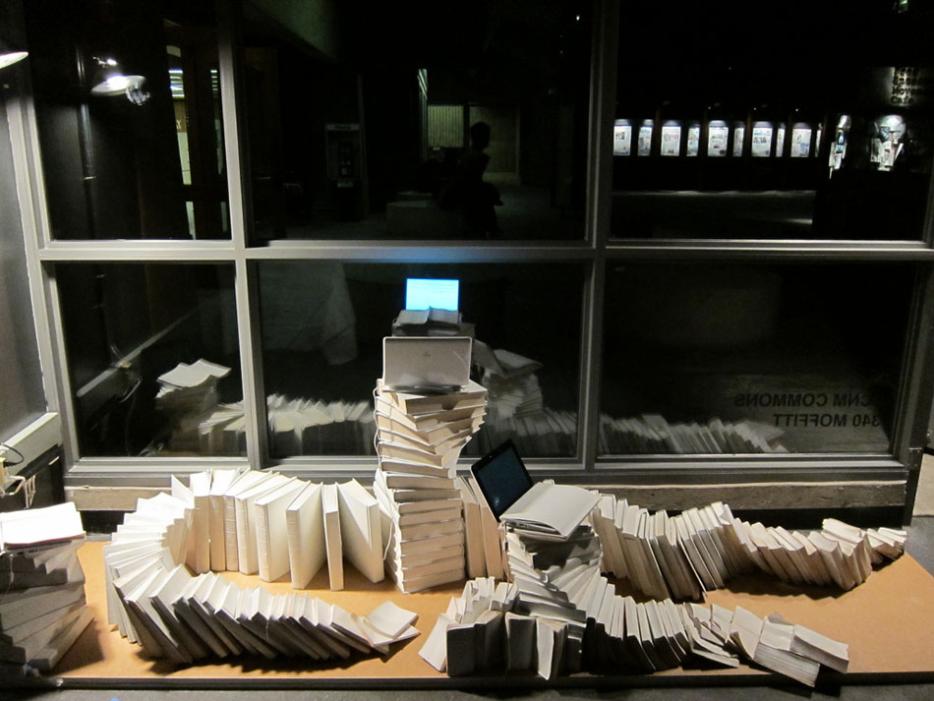

In response to the surprising information about e-readers, Carr argues that the advantages of the devices—their convenience, primarily—may be limited to specific forms, such as genre fiction or, specific situations, like being on a plane. What underpins the notion is Carr’s belief that serious reading is better suited to the focus, materiality and familiarity of the print book. The e-reader is one step away from that ideal form, and the do-it-all tablet an even deeper corruption. To Carr, the artistry and cultural significance of the novel and ‘The Important Work’ are indivisible from their bound physical form, and the slowing growth of e-readers is not simply a sign of the iPad’s popularity, but also that many people are recognizing that they like print for ‘real reading’.

For his part, techno-friendly Shirky objects not by defending the inherent worth of the e-reader or tablet. Instead, he suggests something far more radical: that “maybe books won’t survive the transition to digital devices, any more than scrolls survived the transition to movable type.” His point is that there is nothing inherently valuable in the form of the book, print or electronic; rather, it is simply an effect of the history of the technology and book production. For Shirky, what “half a millenium of rehearsed reverence have taught us to regard as a semantic unit, may in fact be a production unit.” What comes next may not even be a book at all, but the kind of multimedia experience that tablets offer, but e-readers cannot.

Strangely, then, for both thinkers, the grey screen of the e-reader is equally undesirable, if for different reasons. On the one hand you have Carr’s purely aesthetic argument, suggesting that we must fight to protect what is good and true against the forces of free-marketism and techno-fetishism; and on the other, Shirky’s idea that e-readers are less wildly popular because the form they peddle is itself only a temporary blip as we shift to something else.

To Carr, the artistry and cultural significance of the novel and ‘The Important Work’ are indivisible from their bound physical form, and the slowing growth of e-readers is not simply a sign of the iPad’s popularity, but also that many people are recognizing that they like print for ‘real reading’.

There is something important being elided in the debate, however. In the early 20th century, literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin suggested that the novel was not only the result of a kind of aesthetic ‘evolution,’ but also the only form that could take the new phenomenon of multiple ideological perspectives and place them in dialogue with each other. Thought of this way, the novel was certainly a response to advances in bookbinding and distribution, but its very complexity and artistry also had a cultural root and function specific to its time.

It’s this important idea that Shirky’s notion of a ‘production unit’ glosses over, which weakens his approach considerably. At the same time, Carr’s reverence for the work of art and authorial consciousness seems to resist the concept that these things too are historically contingent, suited to their age, but not necessarily to another. That the individual voice or novelistic whole was so important in one millennium does not necessitate that they will be in the next. As radical as it may seem, perhaps what humanity will need from art in the coming decades and centuries is precisely the sort of ‘post-book’ to which Shirky alludes.

The dedicated e-reader thus sits in a strange space. In effect, it simply does to books what the iPod did to music: it simplifies the delivery of the art we experience, but it does not fundamentally alter the nature of the art itself. And like those old classic iPods that carry vastly more music than a smartphone, the Kindle and Kobo and other e-ink devices may well become niche products for but a few people who value the convenience of digital, but enjoy the specificity of a dedicated device. It’s a fact that makers of e-readers have themselves seem to have recognized: Amazon and Kobo now push their own tablet-like devices as much as they do their e-readers.

Meanwhile, the e-book will probably find its primary home on tablets and phones. And it is likely there that the tension between Carr’s and Shirky’s ideas will play out. As the form of delivery changes, it is probable that the type of content will too. We’ve already seen the e-book branch off into a multimedia experience, or a series of tweets turned into a story. That’s just the start, and we could also see a new art form that supplants the book, a form of the novel or non-fiction work that is unrecognizable to us today, or even simply a recognition that print simply ‘works.’ At the same time, it will behoove us to remember what it is we ask of art and intellectual discourse: that they frame the world both as it is and as it might be, so that we might make both it and ourselves better. And, scary as it may seem, we must at least be open to the notion that such ideals will, in the future, perhaps not be best served by what we know as ‘the book.’