“Do you know what was going on here today?”

The man at the hot dog stand, bundled up in his beaten-up winter coat and ushanka hat, passed me the goods. As I handed him a pocketful of change in return, I told him about the Black Lives Matter march that started at Nathan Phillips Square here in Toronto and ended at Yonge and Dundas. His eyes went wide.

“You mean for that boy they killed?”

He was speaking, of course, of Michael Brown. But he could have been referring to over a dozen other boys and young black men killed by police since that hot afternoon in August. Darrien Hunt, a cosplayer chased down and shot to death by officers Matthew Schauerhamer and Nicholas Judson for allegedly swinging a fake sword at them in Saratoga Springs, Utah. VonDerrit Myers, Jr., shot by off-duty St. Louis police officer Jason Flanery not far from the spot where Brown lay dead and uncovered for hours. Tamir Rice, shot by Cleveland officer Timothy Loehmann for playing with a pellet gun in a park nearby his home.

The vendor could have meant Jermaine Carby, gunned down in September by a Peel Regional Police officer whose name hasn’t yet been released. And the vendor would be correct; the march was organized in part to demand justice for Jermaine. One of the speakers that afternoon was Jermaine’s mother, Lorna Robinson, who pleaded with the audience to demand more accountability from our police. “Because,” she said, her voice breaking, “I hope none of you ever go through what I’ve had to go through.”

I told the man at the hot dog stand that we were here to show solidarity with those families, and to send a message to our police.

“You people are so patient,” he told me as I splashed my hot dog with barbecue sauce. I know he saw me flinch as he opened that sentence, but he carried on anyway. “I bust my ass and work behind this stand all day to feed my kids. That man was working what he could to feed his kids.” He was talking about Eric Garner, who was allegedly selling loosies in the street when NYPD caught up to him. “Selling cigarettes, who cares? Is he hurting anybody? And they kill him for this?”

This man had obviously been waiting a while to have this conversation with receptive black ears.

“They kill a boy in the street like a dog. This is what they call serve and protect?” He pointed behind me, to a police cruiser parked curbside. The words were there, in bold cursive across the front fender. “How can you say you protect anyone and then take their child away?” He pulled a Coke out of the cooler and handed it to me with the styrofoam box. “I work here all day to provide for my boys. All day. I work, I make sure they do their homework. Those are my children, I provide for them. And you just come and take them away from me? I tell you, anyone takes my boys away from me, I kill you worse than you killed them.” He tells me about his home country, tells me that no one, law enforcement or not, could take a child’s life so casually without tasting the fear of family retribution.

I wanted to tell him that that’s not how we’re supposed to do things. I wanted to tell him that our responsibility is never to sink lower than our oppressors, but the unspoken words twanged discordantly in my mind—could I rebuke this man’s anger without making a hypocrite of myself? When I read the stories of these murdered boys and the tears boiled up out of my face, did the heat of anger not rise with them? Had a familiar old hatred—one that I’d been taught as a young man to suppress—not wormed its way back into my heart?

*

The killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012 introduced “The Talk” to mainstream audiences—the one black parents must have with their children. The one to explain that, when dealing with police and inquisitive white people, their lives could depend on being as unthreatening and compliant as possible. There’s another conversation that our parents have struggled with for generations, one for which we still haven’t found a name. The conversation that black parents use to help their children navigate a world that not only wasn’t made for them, but often seems formed to separate and destroy them. How to deal with a world that demands you perform twice as good for half as much. Where mediocrity is failure, and success is just managing to stay afloat. Where poverty, crime, and violence define you until proven otherwise.

In other words, how to deal with being treated like a nigger.

The spectre of niggerdom isn’t only summoned by racist people letting their masks slip. A world built on an unreconciled history of racism requires more of the nigger than to allow himself to be identified by name. That world requires the nigger to be its sin-eater; to allow his agency to be robbed, and his flesh to be mortified.

There’s a particular flavour of anger that comes with being treated this way, spiced with hatred, and sorrow. None of us, no matter how young we are, or how high we might rise, are immune to this treatment, or to the anger. When the world heaps niggerdom on our shoulders, it has the audacity to demand we pay by performing a certain kind of nobility. That we disciple ourselves to its sanitized version of Martin Luther King by rising above circumstances—circumstances that no one created, and for which there’s no one to blame but ourselves—and carry on like tireless mules. And in carrying on, we must keep that anger hidden from everyone, including ourselves.

I have carried this anger since the day I played tag with friends, and a white man told us niggers to stop running across his grass. Carrying it for so long, it becomes easy to recognize in others. I recognized it in Joshua Ho-Sang, when his GM called him a “Harlem Globetrotter,” and a Leafs prospector believed he was “too intelligent for his own good.” His simmering anger at being treated as a nigger came off as hardly more than a curiosity to the Sun reporter who interviewed him. I saw it in Akio Maroon, the organizer of the Black Lives Matter march. She recounted for me over lunch that, while she crossed the street with her daughter this summer past, an old white man groped her backside. When she wheeled around on him in anger, onlookers came to the defense of the kindly looking man that had sexually assaulted her only seconds earlier.

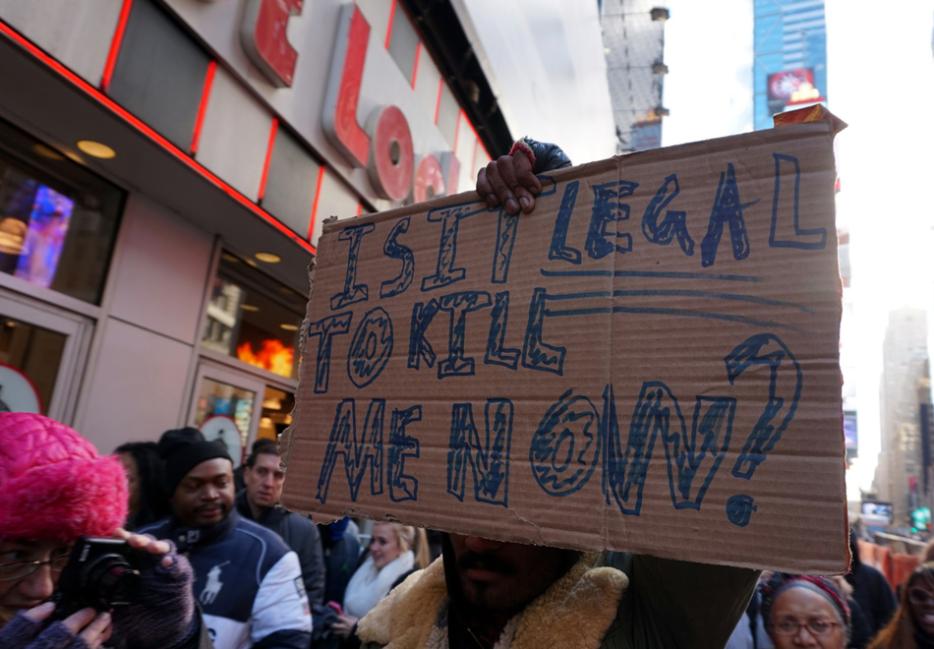

I see it in the woman who held this protest sign, reading “When I was a child white boys told me I was ugly and compared my skin to feces.”

I didn’t have an answer for the hot dog vendor. I don’t think he expected one. When he blew a sigh and called my people patient, he was telling me he couldn’t bear living inside the skin of a nigger. I thanked him and wished him happy holidays.

*

At this time last year, we were deep into the retrospectives and biopics on the departed Nelson Mandela, looking back at an era best left behind, and best unforgotten. An era of riots and burned-out buildings. Of the nightstick and the fire hose, of black bodies shredded by automatic weapons fire, all justified by doublespeak vomited from lying white mouths. When hatred and fear was covered with the gossamer fabric of tolerance.

For the sadness of seeing him go, I also carried optimism. I felt it while watching the deceased black President of South Africa eulogized by the living black President of the United States—a moment I could never have imagined that day I was baptized a nigger by a stranger, or that night when I cried myself to sleep. I heard this optimism in the outpouring of grief and condolences from everyone worth putting in front of a news camera. If Stephen Harper and Maya Angelou could be on the same side, maybe we were finally starting to get somewhere. Mandela’s life was a volume of struggle against racism, and his death the bookend. It was time to move on.

2014, in many ways, felt like a long, cruel object lesson in disappointment. We were supposed to be better than this, and yet, should we really have expected better? The reaction to Richard Sherman, surging on adrenaline from the Seahawks’ NFC championship game, labeled a nigger for his post-game trash talk. A very angry woman whose recorded run-in with a “racist fucking nigger” went viral. Justin Bieber’s comfort and ease with singing a ballad about reducing the world’s lonely nigger population by at least one. Donald Sterling encouraging his mistress to fuck black men if she really needs to, but drawing the line at bringing them to Clippers games.

I didn’t want to know these things, and I didn’t want to have to deal with them. I didn’t want to be dragged into in these conversations every time I turned on the television. I didn’t want to be approached by co-workers for my thoughts, didn’t want to be tagged into Twitter and Facebook conversations by friends and online acquaintances to debate the virtue of being treated like a human being. But the most intractable problem of niggerdom is its inescapability. It doesn’t allow you to just turn off a TV or cut a conversation short. It follows you everywhere, reminding you of its presence every time store security pays you too much attention, and store clerks none at all. It lurks behind every taxi that blows by your invisible self, and every police cruiser that homes in on you from afar. A nigger doesn’t get to not deal with these things.

But the spectre of niggerdom isn’t only summoned by racist people letting their masks slip. A world built on an unreconciled history of racism requires more of the nigger than to allow himself to be identified by name. That world requires the nigger to be its sin-eater; to allow his agency to be robbed, and his flesh to be mortified.

That world required the shooting of a teenager for having his music turned up too loud, a man carrying store merchandise inside a Walmart, a man following an officer’s instruction to retrieve his driver’s license, and a man walking down the hallway in the apartment building where he lived.

It required us to know the names of the dead, for their lives are autopsied in public, and the crime of their niggerdom to be prosecuted even before the bodies are slammed into the mortuary drawer. It required us to know whether their family, friends, and associates were guilty of the same crime. Within days, we knew about the rap sheets on Tamir Rice’s parents, about Eric Garner’s run-ins with the police, and of Jermaine Carby’s criminal history.

We did not know that, two years before he shot a 12-year-old in the stomach and watched him bleed to death, Timothy Loehmann had already been deemed unfit for policing by a previous department, and subsequently fired. We did not know that Daniel Pantaleo had already been sued twice for racial profiling—one of those suits alleging the humiliating search of a man’s genitals. We still don’t even know the name of the Peel officer that shot Jermaine Carby and cuffed his lifeless hands as he lay facedown on a Brampton road.

*

After the Black Lives Matter march ended, I walked over to the Yonge and Dundas entrance of the Eaton Centre. Protest signs had been arranged on the street. A black mother and her two sons stopped next to me to look at them. After I introduced myself, the younger one, about six or seven years old, asked what the signs were on the ground for.

“Because people were protesting the police shooting young black men.”

The most perplexed look crossed his face. “Why are they shooting black men?”

“Young black men,” his mother corrected. I noticed she hadn’t answered his question.

“Why?” he asked again.

She had no answer for him. The Talk had caught her unaware. A busy intersection, with a stranger standing next to her, was not a safe space to have this conversation with her son. Besides, too much of what he needed to know was laid out right in front of him. Arranged on the street was proof that his life could be judged to have no value. Proof that if, on some fateful day he crossed the police, his life and that of his family would be publicly examined long before the culpability of the officer who snuffed out his life. Proof that his people would be called on to explain why he should not be strangled and left to die on a piss-stained sidewalk. Why his height, weight, problems in school, medical history, or previous exposure to law enforcement wouldn’t be more responsible for his death than the officer who killed him.

The corner of Yonge and Dundas was no place for a black mother to teach her son how to avoid becoming another dead nigger.

“Sometimes these things happen,” she finally said. “So we have to show them it’s not okay.”

I watched as he turned that over in his mind for a moment. I knew he knew, and the anger would soon find him, too.