The other day I was riding a New York subway train—the G, I think it was—and it might have been raining. My boots were wet, in any case. But it was 5:40pm; I was headed home. Then I saw her, wearing a fuzzy hood and multicoloured socks, and soon after I composed these lines to post as a missed connection on Craigslist:

You looked at me oddly when I sat down across from you, Proust in hand. I'd have done the same thing if I'd seen someone so (seemingly) pretentious. We got off at Greenpoint, then started together toward the exit—that is, until I remembered I lived in the other direction and turned around. I wish I hadn't. I'd love to talk Proust-y to you sometime.

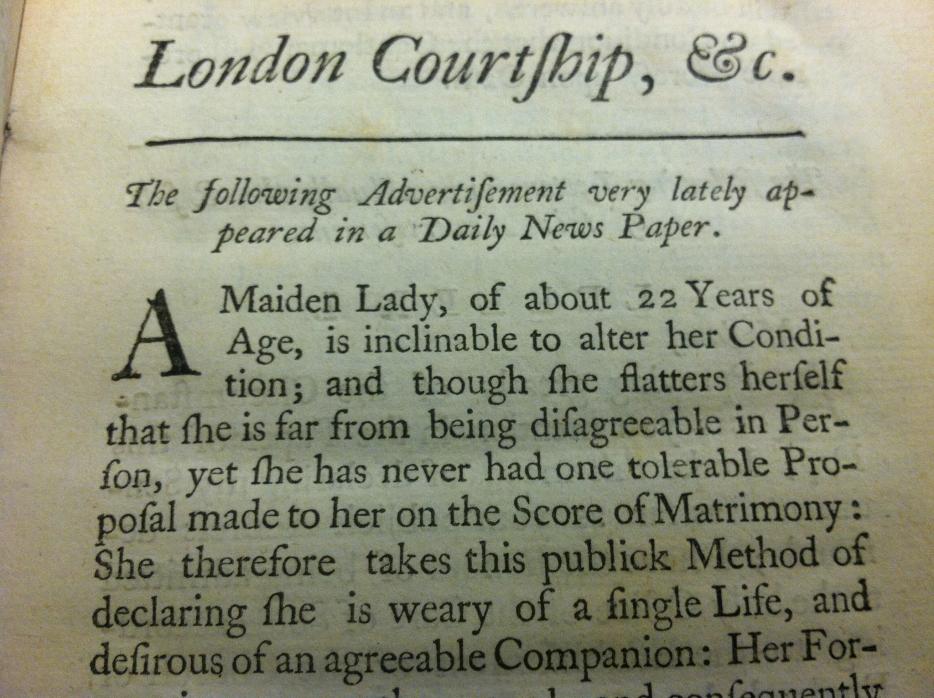

Wordsworth I’m not, though the G train does run some miles from Tintern Abbey. And yet even the poet himself might have recognized the form of my note. In 1841, nine years before Wordsworth’s death, a 70-year-old German aristocrat published an advertisement for a wife that feels remarkably contemporary, even now. “She must be from 16 to 20 years of age; she must have beautiful hair, handsome teeth and a charming little foot,” the lonely baron wrote, receiving 700 letters in reply.

Personal advertisements—known as “lonely hearts columns” in Britain—have remained largely unchanged since their beginnings in the 1690s, around five decades after the appearance of the first modern newspapers. Then, as now, men looked for women to marry and women for men; people of both sexes advertised for chaste companionship; gay men and women found each other through carefully coded sentences innocuous to the searching eyes of the law and those who would otherwise censure them. And on, over the 300-odd years between here and there.

Today, it almost goes without saying, we have more opportunities to connect with each other than ever. Over burbling jazz and bubbly art at a friend’s opening; over a mutual dislike of Nicolas Cage’s later oeuvre at a café; or as a simple swipe on a cute face. And so forth, so it goes.

Here is where personal ads differ, though, and why they’ve persisted despite the ascendancy of their varied spiritual successors, like OkCupid and Tinder and round after interminable round of speed dating: you can’t post a personal ad without feeling an element of wistfulness, of near-infinite possibility, a sense of throwing caution to the wind. You can feel it when you read them (the good ones, at least), coupled with a heady dose of voyeurism. It’s the self, commodified in yet another way: a personal is a meticulously crafted self-portrait that, like any good painting, reveals the future as much as it does the present—we’re seeing ourselves as we are while we reveal who we want to become, what we want to be seen as.

From what I can glean from Google and his Twitter profile, Dr. Harry Cocks—a lecturer at the University of Nottingham—is a pair of handsome terriers. Nevertheless, his book Classified: The Secret History of the Personal Column gives an insightful glimpse into the occasionally fraught history of the personal ad.

“Advertising for love has always been disdained by the mainstream press and commentators on social mores, but has also been a consistent presence in Western culture since the rise of print,” he wrote me in an email. “There are not many figures—though there were about 30 matrimonial newspapers in Britain in c.1900 and one editor claimed in 1893 to deal with 300 clients a fortnight while another claimed credit for 20 marriages a week and over a thousand a year.” Ads placed for platonic companionship came later, around 1913, most notably in The Link (1915-1921), a British personals paper whose editor was censured for “corrupting public morals.”

In terms of genre, personals work like any other literary form. There are a few constraints—pithiness, a sprinkling of wit, an extra helping of need, the stating of one’s desire—but they remain remarkably consistent across publications and platforms. Personals have been a feature of The New York Review of Books since 1963, The London Review of Books since 1998, the WORD bookstore in Brooklyn since 2010, and n+1 from 2011-2012 (RIP). (That’s not to mention, of course, the occasionally beautiful Craigslist missed connection.) All this said: though I’ve heard apocryphal success stories, I don’t believe there’s any hard data available on their efficacy. Which perhaps adds to their mystique.

For his part, Dr. Cocks assured me that linguists and other assorted social theorists do, in fact, study personals as a form. My own interest is less scholarly and more desultory than the theorists’—which is how I found myself on a patio in Brooklyn speaking with Kaitlin Phillips, the mind behind n+1’s regrettably short-lived foray into offline dating. These personals attracted the hopelessly pedantic and hopelessly erudite, the neurotic self-styled intellectuals of all stripes; like many others I was a voyeur—and boy, was there a lot to see.

1. Might pay to see this one chain cigarettes

Woman seeking former child prodigy fluent in Middle English and oral sex. Under 150 pounds; height is not immaterial, must be over 6 feet. Smokers only. I’m not particularly caring or generous but I have cool friends and good taste in film.

2. Pretty casual with those modifiers, bro!

Mid-40s, casual hero, somewhat unconventional, taller than you in heels—likes Formentera, absinthe, Orwell, and long walks. Seeking curious female, late 20s, recovering Communist or Anarchist, non-scene whore for adventures of mind and body.

“To understand n+personals, you have to understand n+1,” Phillips told me over a glass of red wine. “It’s not very top-down.” I wasn’t sure what she meant, but I took it to mean the operation was, in those days, more haphazard than it appears to be now. Wind brushed past the flock of sunflowers beside us, and she took another sip before she continued. “I started it as an intern, in my sophomore year of college,” she told me. “I think everyone thought it would just die or it would be a non-starter. It got out of control very quickly.” She’s right; in the short time it existed, the site managed to take on a life of its own, with even the venerable New York Review of Books offering to swap ads. And then, suddenly, there came the announcement that the site was shutting down:

At the best of times, an n+personals mixer was even entertained—dance me to the end of love, etc—but who are we to externalize our readers’ discontent? At this rate (responses average 5-6 a week; more than 50% of ads get one contact request), we could continue the personals into perpetuity. If, well, we had some perpetuity.

My theory is that the site shut down because it became too much for one intern to handle. N+1’s audience—pedantic, erudite, literary, youthful—is considerable, and connecting people with putative love is exhausting. Which is why we’ve got computers to do it for us, now. But algorithms, though beautiful, miss the nuance of the literary; no code construction can convincingly emulate need (yet).

The thing about personals that spins them out of control—the thing that keeps us coming back to trawl Craigslist’s missed connections, day after day, week after week, the thing that encourages us to post them in the first place—isn’t complicated: We are built for electric connection, and nothing gives a charge quite like risks with an equally high chance of failure or reward.

When I think of personals, I come back to the image of Voyager 1, our lonely emissary to interstellar space. The probe carries within it a record, a golden disc engraved with our shared memories of Earth. What’s a personal ad if not a probe shot out into the deep space between people, carrying a tiny kernel of your story?