One morning in August 2009, the Idaho-based writer Johanna Harness (author of the self-published novel Spillworthy) was sitting at her computer feeling “alone with my writing,” as she wrote to me in a recent email. “I wondered who was writing in the early morning hours the way I was.” So Harness, an active Twitter user with over 35,000 followers, appended the hashtag #AMwriting to a tweet as a way to reach out to everyone else engaged in their morning writing. The response was immediate. “I had people from all over the world writing back,” Harness recalled. One problem—it wasn’t morning in every time zone. #AMwriting, then, turned into #amwriting, a first-person declarative statement signifying entrance into a state of furious writerly activity.

Over the past six years, the hashtag has gone viral beyond Harness’s wildest expectations. There are hundreds of #amwriting tweets an hour, every hour of the day. The tweets express the frustrations of editing, collect snake-oil cures for writer’s block, and turn writing into a kind of endurance sport where the more words you write in a day, the better. (“Writing: like running, only the sweat is your tears. Read my blog for more!” as Jennifer Ammoscato tweets.) Tumblr’s version of the hashtag is home to a collection of image macros of writing advice and reaction GIFs about the joys and frustrations of creating fiction. (Do you feel like a Disney princess when writing fantasy?) On Instagram, writers post streams of #amwriting photos of their laptops perched on various cafe tables, perilously close to full coffee cups, ready for action.

#Amwriting makes it easy to take on the mantle of the writer, a historically elite identity that the growth of digital self-publishing has helped to democratize. Just tweet or take a photo, add the hashtag, and you’re a writer, too—no MFA or agent needed, those old signifiers of ever lessening significance. The more easily shared symbol of the hashtag seems to serve more in celebrating the very act of writing, building a community around what has traditionally been a solitary activity. Yet the meme may have also made being a writer that much more exhausting. Community is great for creating support networks, but it can also dampen diversity and lead to a sense of exclusion for those who don’t echo its norms. Constantly proving you #arewriting invariably leaves less time to actually write, but if you’re not following along with #amwriting, are you really still a writer in the eyes of the Internet?

Allow me to offer a simple formula: If you are tweeting about writing, then you are not writing. At its worst, the hashtag can be a slow poison that reinforces bad habits instead of creating better ones. The very same social media that hosts #amwriting also forces distraction right into the process of writing, as Jonathan Franzen has pointed out in his bilious attacks on Twitter. Franzen takes his critique to a needless extreme, but the point stands that once we’ve established our identities as writers online, we are forced to maintain them—to continue the public performance of being a writer—no matter how the work itself is going.

If you’re active on social media, suddenly going silent isn’t so much proof of work getting done as a hint that you might be dead and friends should check up on you. I freely admit that in the time I spent composing the first several paragraphs of this piece, I checked Twitter multiple times, posted an image of my own workspace to Instagram, and then looked back to see how many people liked it—repeatedly. My #amwriting-style social media output has become a part of my writing career, even though I often suspect it shouldn’t be.

A 2011 essay in n+1 called “#amwriting” by the novelist Dani Shapironarrates this experience of being a writer in the age of the Internet, when public writing brags can be instantly met with positive feedback. We get addicted to the validation. Shapiro tests out Freedom, an app that blocks the Internet for a set amount of time. After using it for an hour and finding it effective, she’s “tempted to go on Twitter and tweet about this phenomenon… or announce it as my status on my Facebook page.” Even when we’re offline, we’re online in our heads, constantly measuring the reality of our work against its Internet presence.

This gets at my central problem with #amwriting: its persistence encourages writers to think not about what they’re writing, but about the optics of their practice. We worry over how our tweets, Instagrams, and witty observations about the writing life play to our followers rather than what’s going on with the text in our empty Word documents. An ostensible sign of productivity has become an outlet for marketing and self-branding—a promotional tool for building an online presence that might ultimately sell books or articles, but in the meantime doesn’t contribute much to finishing them.

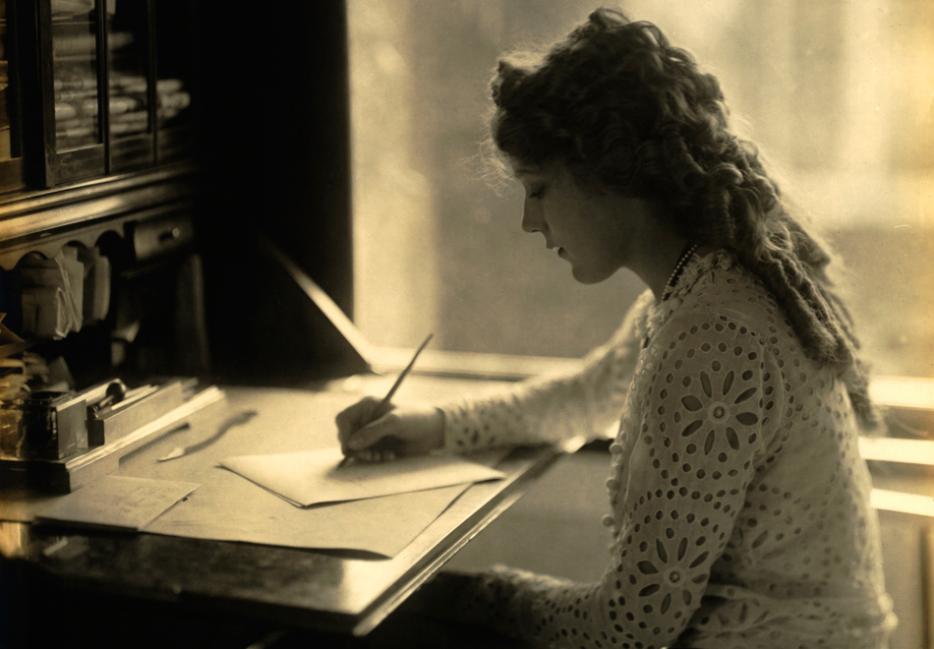

And while the community the hashtag inspires shouldn’t be discounted, a cacophony of voices at all hours of the day isn’t necessarily conducive to thinking independently, either. Though the image of the writer scribbling away in the lamplight behind closed doors may be a reductive stereotype, a certain amount of quiet isolation often is helpful. Another, perhaps more realistic stereotype of writers is that we are easily distracted, seeking out any excuse to get away from the task at hand. In reality, participating in the community is just such a procrastination tool, whether for a novelist navigating a fantasy world or a journalist trying to polish off a feature. Michel de Montaigne, a 16th-century writer prized by bloggers for his loose, meandering voice, had cats instead of social media to distract him at his desk, but he, too, realized the danger of worrying too much about other what other writers were doing. “There are more books on books than on any other subject,” he wrote in his 1580 Essays, “and all we do is comment upon one another.”

I don’t mean to dismiss the benefits of #amwriting; as a freelance writer, the online support group I’ve found through Twitter is what keeps me going on a daily basis, even if we don’t use any devoted hashtags. But it’s difficult to know how much to engage and how much to hang back, to prevent getting bogged down. For her part, Harness uses #amwriting not as a distraction but as a way to get to work, creating productive colleagues out of her online counterparts. “When I check in with #amwriting in the morning, it's like stamping my time card,” she explained. “It’s a routine that signals to my brain, ‘You're at work now.’”

At its extreme, though, the hashtag turns those stereotypical signifiers of the writer—coffee cups, crowded desks, anachronistic crumpled pieces of paper—into an unhealthy fetish for The Writer. “The truth is that no environment will ever turn us into writers,” Harness wrote to me. “That motivation has to come from within.” #Amwriting was originally designed to help writers not feel so alone in their work. Now, it might not let them be alone enough.