Collette

I fell in love with her before I read any of her books.

To my teenage eyes smeared in the black kohl I believed made me look nihilistic and wasted (it was the era of punk after all and we were all in mourning for the future), Colette had a self- possessed kind of beauty that I felt she owned and hired to the photographer.

Even better as far as I was concerned, living as I did in the suburbs of London where everyone looked the same and even called their dogs the same name (there were three dogs called Spot in my street alone), Colette was a writer who looked like a movie star.

I looked nothing like her. Her dog was called Toby-Chien.

I don’t know how I chanced upon her photograph. I do know it was a freezing December in 1973 and the central heating had broken down in our family house.

The doorbell rang and my mother shouted at me to let in the man who had arrived to fix the heating. He poked around in the cupboard where the boiler was and said, ‘I officially condemn this boiler. The law says you’ve got to buy a new one.’ Then he winked at me and switched it on. The pipes in the house started to whirr and clank like an old tractor. When I at last returned to my bedroom, I had to fight my way through the black smoke coiling out of my radiator.

Despite it being a very posed image, there was something about the way Colette had contrived its artifice that connected with me. She was a working writer who had a purpose in life. I could see immediately that she was enjoying the theatre of inventing herself to portray this purpose. This was of particular interest in that phase of my own life.

I was born in South Africa and grew up in Britain. When I glimpsed this photo at thirteen years old, I had lived in Britain for four years, not quite long enough to feel that I was English. Colette was presenting herself in a way that appealed to my teenage idea of what a European female writer might be like. Glamorous, serious, intellectual, playful – with a mean, sleek cat sitting on her writing desk amongst the flowers, all of them bathed in a glowing arc of French light.

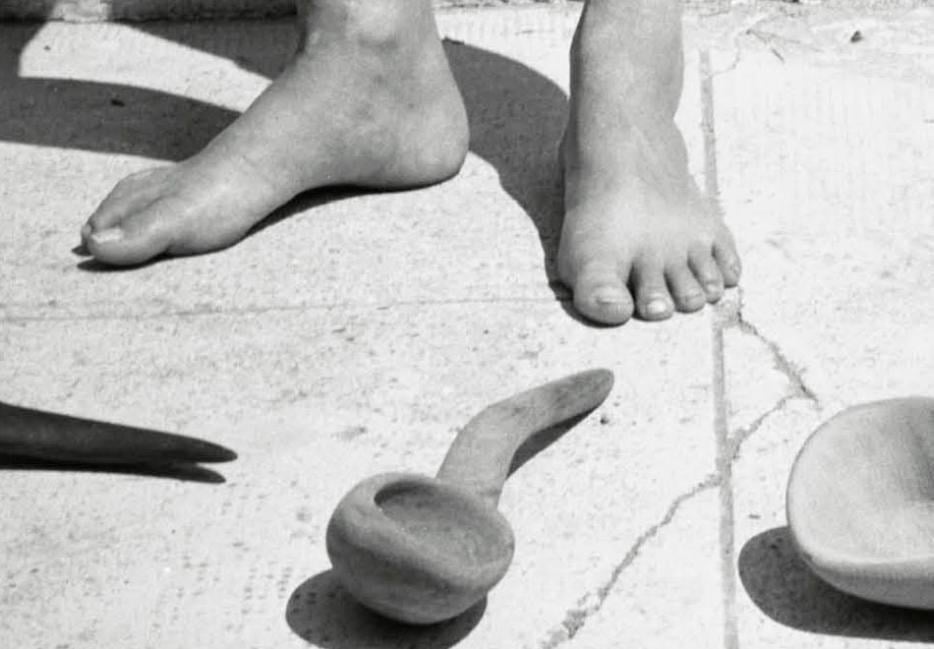

When I started to read her books, all that was transgressive and sensuous in her writing blew like a wind from Burgundy, Paris and the South of France into the damp suburban gardens of London. Her affairs with women and her three marriages (the first to a perverse and corrupt bon viveur who signed her early novels as his own) meant she had one foot in and one foot out of the bourgeois life of her era. She became arthritic in middle age and often wore mannish open sandals with her elegant dresses, much to the agony of her more conventional second husband.

I knew none of this when I first glimpsed the photograph, yet somehow I intuited she’d had an experimental life.

What is the point of having any other sort of life, I thought to myself. Outside I could hear one of the dogs called Spot barking at a cat called Snowy. Twenty years later, when I read The Vagabond, I had cause to agree with her light but slyly deep assertion, ‘I want nothing from love, in short, but love.’

Yes, what else is it we would want from love, apart from love?

Too many things, as it happens.

Marguerite Duras

The purpose of language for Duras is to nail a catastrophe to the page.

She thinks as deeply as it is possible to think without dying of pain. It is all or nothing for Duras. She puts everything in to language. The more she puts in, the fewer words she uses. Words can be nothing. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing.

It is what we do not do with language that gives it value, makes it necessary. Dull and dulling language is successful. Every writer knows this, makes a choice about what to do with that knowledge.

It’s hard, sometimes even absurd, to know things, even harder to feel things – that’s what Duras is always telling us. Her films are novelistic – voice-over, interior monologue – her fiction is cinematic: she understands that an image is not a ‘setting’ and that ‘it has to hold everything the reader needs to know.’ Duras is never begging with words but she is working very hard and calmly for us. Her trick is to make it all seem effortless.

Translated European literature was once shockingly hard to find in Britain. I was twenty- nine when I first read Margue-rite Duras’s 1984 masterpiece, The Lover, translated from the French by Barbara Bray. A revelation and a confrontation in equal measure, it was as if I had burst out of an oak-panelled nineteenth-century gentleman’s club into something exhilarating, sexy, melancholy, truthful, modern and female.

If its cool, spare prose and flawless narrative design was somehow representative of the nouveau roman, largely associated with Alain Robbe- Grillet, it was clear to me that its major difference was that Duras did not distrust emotion. To write The Lover she drew on her early years living in Saigon with her impoverished mother and belligerent brothers. Structured as a kind of memoir, it is about a teenage girl living a peculiar colonial existence in French Indochina in the 1930s with her genteel but ‘beggar family’.

She decides to make something happen and starts to wear a man’s fedora hat and gold lamé shoes. In so doing, she suddenly sees herself ‘as another’. It’s a magic trick to separate from her deadening mother, and it works.

An elegant, wealthy Chinese man, twelve years her senior, is watching her on the ferry bus that crosses the Mekong River. When he risks offering her a cigarette, she notices that his hand is unsteady. ‘There’s the difference of race, he’s not white, he has to get the better of it, that’s why he’s trembling.’

She wants to make him ‘less afraid’ so that he can do to her ‘what he usually does with women’ and, perhaps in return, he might sometimes buy her brothers and mother a meal? In one of the most devastating and brutally truthful seductions ever written, the Chinese financier who, she discovers, owns all the working-class housing in the colony, drives her in his ‘funereal’ limousine to his apartment on the edge of the city.

She undresses him, notices she desires him, panics, tells him he must never love her. Then she cries – about her mother’s poverty and because she often hates her. The Lover does not just portray a forbidden sexual encounter of mind-blowing passion and intensity; it is also an essay on memory, death, desire and how colonialism messes up everyone.

I’m not convinced a book as incandescent as The Lover, more existential than feminist, would be published today. Not in Britain, anyway. Questions would arise. Are the characters likeable (not exactly), is it experimental or mainstream (neither), is it a novel or a novella? Fortunately for Duras, it didn’t matter to her readers. It sold a million copies in forty- three languages, won the Prix Goncourt and was made into a commercial film.

Marguerite Duras was a reckless thinker, an egomaniac, a bit preposterous really. I believe she had to be. When she walks her bold but ‘puny’ female subject in her gold lamé shoes into the arms of her Chinese millionaire, Duras never covertly apologizes for the moral or psychological way that she exists in the world.

Ann Quinn

I recognize some of my own influences in Quin’s writing. Her literary taste and aesthetic enthusiasms were European – Duras, Robbe-Grillet, Sarraute – and I’m guessing she must have read some of Freud and R. D. Laing.

I know how lonely she must have felt in Britain at the time she was writing. No wonder she scarpered as soon as her debut novel, Berg (1964), had earned her a ticket to travel to Europe and America. I know she understood she was on to something new and that she took herself seriously, in the right way; she had a serious sense of her literary purpose.

Quin had worked as a shorthand typist for a while, just like my own clever, book-loving mother. Both women were born in the 1930s, and again, like my mother, Quin (apparently) applied to enter university as a ‘mature student’. It was hard for a working-class woman to get herself an education. Even Virginia Woolf found it a struggle to achieve a formal education, though her father had a well-stocked personal library. Presumably Quin made use of public libraries – and she would have read everything that John Calder, her heroic publisher, might have slipped her way.

Quin was reaching for something new and bewildering in each of her four published novels – the effort and exhilaration of that reach must have sustained her when life was tough. It is not vulgar to comprehend that she was ambitious for her work. Obviously, she put in the hours to design composition and cadence, to find a conceptual scheme to hold her ideas, to explore new possibilities for satire, shifts of viewpoint and voice. That’s what writers are supposed to do.

It would be progress if we could stop the rhapsodizing of Ann Quin and just read her books without having to defend them. It’s hard not to defend them, though. Few critics gave her books the respect of a close reading. It was as if Quin was culturally forbidden to actually possess a coherent literary purpose. The word ‘experimental’ kept her nicely in her place.

As it happens, I believe that if she had managed to swim back to the cold pebbles on Brighton beach that day she drowned, she would have gone on to write books that were nearer to herself. I want to know more about what it takes to want to swim home and I know Quin could have told me.

Reading Violette Leduc’s Autobiography, La Bâtarde

At the age of five, of six, at the age of seven, I used to begin weeping sometimes without warning, simply for the sake of weeping, my eyes open wide to the sun, to the flowers . . . I wanted to feel an immense grief inside me and it came.

La Bâtarde (1964) is a harsh title for an autobiography that is full of animals and children and plants and food and weather and girls falling in love with girls. It’s true that Violette Leduc was the illegitimate daughter of a domestic servant who was seduced by the consumptive son of her employer, but to choose such a melodramatic and reductive title, ‘The Bastard’, tells us how hard it was for Leduc to escape from the way her mother described her, and in that description gave her daughter an internal crucifix on which to nail her life’s story.

It’s not surprising, then, that the furnace at the centre of Leduc’s autobiography, and indeed all her writing, is stoked by her ambivalent steely-eyed mother, of whom she writes: ‘You live in me as I lived in you.’ Yet if the young Violette’s tears spill from eyes that are open to the sun, the older Violette’s words spill from the same place too. She is not blinded by her tears, nor are her eyes shut to the pleasures of being alive. Which is to say, Leduc was a writer very much in the world despite the distress she suffered all her life. What’s more, she was a writer who was going to give maximum attention to the cause of her distress and create the kind of visceral language that often irritates men and makes women nervous.

This is because Leduc experiences everything in her body:

As Isabelle lay crushed over my gaping heart I wanted to feel her enter it . . . She was giving me a lesson in humility. I grew frightened. I was a living being. I wasn’t a statue.

She doesn’t just (infamously) describe the physical sensations of sex between women, she describes the physical sensation of being unloved, the physical sensation of poverty, of snow, of war, of peacocks chuckling in a meadow – she is tuned in to the world with all her senses switched on. This is an extraordinary (and impossible) way of being in the world, but for Leduc it was ordinary. She is a writer who energizes whatever she gives her attention to, an orange shrivelling in the sun, an ink stain on a table, the white porcelain of a salad bowl. Leduc refused to bore herself. Nothing is decoratively arranged to suggest atmosphere or a sense of place or to set a scene. Everything on the page is there because the narrator perceives it as doing something.

Even as a young girl, Leduc knew she had to find her own point to life. Her mother wanted her to be a Protestant, the religion of her absent father, but every time Violette tries to hear God, there is only absence. When she describes watching her beloved grandmother pray in church, Violette is shocked to realize that although she is sitting next to her, she has lost her. At that moment her grandmother is not there; she is in communion with somewhere else while Violette is doomed to be here, to be present, to be in this world. This is no small matter if you’re poor, female, a bit bent, not that attractive (Simone de Beauvoir referred to her as ‘the Ugly Woman’), and have nothing but your cunning and your talent to buy you bread. We know that Leduc’s equivalent of the prayers that transported her grandmother elsewhere will be language. With words she not so much found the point to life as sharpened life to a point.

The French essayist Antonin Artaud, who was sometimes mad, wrote: ‘I am a man who has lost his life and seeking to restore it to its place you hear the cries of a man remaking his life.’ Is that why people write autobiographies? Are they attempting to remake their lives? La Bâtarde is not an attempt to remake Leduc’s life, although there is no doubt that writing books was her salvation.

It is probably an attempt to stage her life and in so doing witness herself as its main performer – and what a performance. By the time she wrote her autobiography, Leduc had lived through two world wars, had intense and volatile affairs with women – the end of a love affair, she says, ‘is the end of a tyranny’ – been married and separated, written and published a few novels (in between lugging heavy suitcases of black-market butter and lamb from Normandy to sell to the rich in Paris), worked as a telephone operator, secretary, proof-reader and publicity writer. She also had a relationship with the writer, Maurice Sachs. It was Sachs, a flamboyant homo-sexual, one- time reader for Gallimard, admirer of Apollinaire, Kant, Cocteau, Duras and Plato – not to mention fresh cream cakes, apple brandy and cigarettes – who encouraged Leduc to write instead of ‘snivelling’ all over him. Leduc portrays him as a sort of French Oscar Wilde, a man both bewildered and fascinated by women, who filled her with terror because of ‘the gentleness in his eyes’. Leduc became infatuated with him because she has a ‘passion for the impossible’. What kind of accommodation can be found, she wonders, with people we deeply love but who cannot give us all we want? What Sachs can do is tell her: ‘Your unhappy childhood is beginning to bore me to distraction. This afternoon you will take your basket, a pen and an exercise- book, and you will go and sit under an apple tree. Then you will write down all the things you tell me.’

It was under that apple tree that she wrote the wonderful first line of her first novel, L’Asphyxie: ‘My mother never gave me her hand.’ Simone de Beauvoir read the manuscript and was so impressed she became Leduc’s mentor, using her contacts to help get it published in post- Second World War Paris. When Leduc’s editor, Jean- Jacques Pauvert, offered her 100,000 francs for the manuscript, she demanded the sum in cash, preferably in small bills.

By the time Leduc wrote La Bâtarde, she was going to return to themes she had written about before (her mother, the deprivations of her childhood, sexual passion, the erotics of everything, coffee, shoes, hair, landscape), but as a writer at the peak of her literary powers. In fact, she was uniquely placed to write an autobiography because she was a novelist who knew how to make the past and present seamlessly collide in one paragraph. Leduc also knew something that lesser writers do not know. She knew the past is not necessarily interesting. Eight lines into La Bâtarde she declares, ‘There is no sustenance in the past.’ This made me laugh, because I was on page one with 487 pages of ‘the past’ to go. She was clever, though. To observe so soon into her life story that there is no sustenance in the past is to give the past an edge. To make us curious about what the past lacks in sustenance for the narrator. What is the past anyway? What kind of place is it? Yes, it’s a series of events that happened before now, but the past, like writing, is mostly a way of looking.

Leduc’s cunning decision was to tell the reader that she is not unique, which is a relief – most people write autobiographies to persuade us that they are. She then goes on to wish she had been born a statue – presumably because if she were made from bronze rather than flesh she would not have to feel the painful things she is going to tell us about. Still on page one, she tells us she is sitting in the sunshine outside, surrounded by grapevines and hills, writing in an exercise- book. Suddenly she imagines her own birth. She is in a dark room. The doctor’s scissors click as he separates the child from her mother: ‘We are no longer the communicating vessels we were when she was carrying me.’

‘Who is this Violette Leduc?’ she asks. And then it’s the next day, she’s picked some sweet peas, collected a feather, and is now writing in the woods, staring at the trunk of a chestnut tree. Every moment has breath and every breath pushes the narrative on to a surprising place, to somewhere that matters because it matters to Leduc. When she steals flowers, ‘always blue’, from a park, she connects the action to a perception. She says the flowers are her way of ‘taking her mother’s eyes back’, by which I think she means she wants to find her mother’s image in something beautiful. And when she is convalescing from an illness in the countryside, she writes: ‘Whenever I looked round at the objects and furniture in the room I felt I was sitting on the point of a needle. So much cleanliness was repellent.’ Her prose is kinetic and it is poetic, but it never collapses into poetry. In fact, her books are much more grounded in the realities and uncertainties of everyday life than some of her existentialist contemporaries.

Despite being acclaimed by Camus and Genet, Simone de Beauvoir and Sartre, Leduc’s books certainly do not stand spine to spine with them in bookshops. Perhaps this is because nothing had taught her (or Genet) that life or literature was respectable. Literature for Leduc was not a comfortable sofa or a seminar room in a university – nor was it a place where flawed human beings undergo some sort of catharsis and emerge happy, whole, healed, miraculously cleansed of anger, lust and pain.

To declare there is no sustenance in the past is of course a half- lie. What sustained Leduc is that she wrote out her life with an audience in mind. It is for this reason she ‘bit into the fruit’ of her ‘desolations’ – that’s what many writers do, and Leduc is no crazier than them for having the audacity to believe they might be interesting. I disagree with Beauvoir, as-tute as she is, when she describes ‘the unflinching sincerity’ of La Bâtarde as written ‘as though there were no one listening’. Beauvoir certainly did not write her own books believing no one was listening to her, and she must have been aware that even in an uninhibited autobiography such as this one, there is no such thing as an absolutely true memory – all writing (except for diaries, but that too is debatable) is shaped with an audience in mind. Leduc, who addresses the reader through-out as ‘Reader, my reader’, felt more entitled to be listened to than perhaps Beauvoir unconsciously thought she should feel.

Violette Leduc had to spend a lifetime unlearning how to see the world as her mother saw it. Most of us choose to be less alert to the things that grieve us. This was just not possible for Leduc.

Excerpted from The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy, Hamish Hamilton 2024.