What were we obsessed with, invested in and plagued by in 2023? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the issues, big and small.

I recently stepped back into an arena that, in truth, I had not fully left. And yet I had needed that distance, whether to have my eyes opened again or, at least, to open my eyes again and look at things seemingly unrelated.

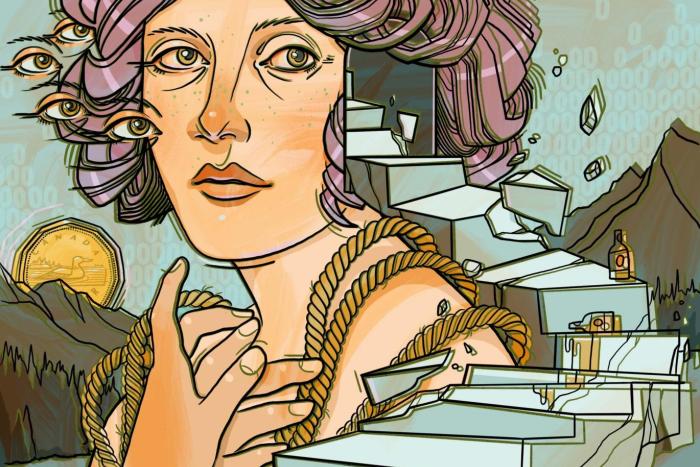

I am an intimacy educator and researcher. I teach rope bondage, and I try to expand its range, definitions, and options.

Another thing one must know about me, especially in the context of my work, is that whenever a term or concept is used in an authoritative way without a satisfying definition, I become skeptical.

I am, one could say, a deconstructivist—not in the sense in which that term circulates widely, as some sort of destruction and reconstruction, but similar to the concept of copy and paste. I take a concept or term and cut it out of its environment, then paste it into another. There I see how it behaves and whether it offers some surprising new insight or “solution.” This technique is not universally successful and often leads to nothing but confusion. Sometimes, though, I discover something unexpected; I hold in my hands a revised concept, or I am suddenly able to look at a term from a completely different perspective.

As an example, let us examine identity. Identity as a concept is so laden with interpretations and meaning that it is hard to say anything about it without stepping into the trap of cliché. I have my issues with many of its interpretations, but I am hard pressed to provide a better or more succinct explanation. How does one handle such a term effectively? In my case, I examined how it behaves when we enter a totally other space, a Foucauldian “heterotopia.”

When he introduced heterotopias—spaces societies have constructed as counter-spaces to our everyday life—Foucault had in mind locations like cemeteries or holiday villages—places we enter through the utterance of a promise; we promise that we behave such-and-such, once we are inside. We walk slower and speak quietly on entering a cemetery; we are louder and less restrained on holiday. The entrance to another space brings with it a different set of contracts, promises, that we (usually unconsciously) agree to by crossing the threshold.

I think Foucault missed an opportunity with his heterotopias, for we follow the same protocol with our identities. When we enter our national identity, for example, we promise—or better, we are asked to promise—to adhere to the laws, to know the anthem, to learn the history, and so on. When we enter our sexual identities, we promise that we are attracted to such-and-such and aroused by this-and-that. Obviously, those promises rarely occur consciously; most are foisted upon us by our environments, while we are young and without our recognizing their significance. Instead, these entrance promises take the form of an installed authority that hovers over the fulfillment of those promises, and which monitors for compliance. In many cases that authority is the shame within us, notifying us when we stray from promises. We have thus assumed an identity, and we will struggle with its promises, feel its shames, and explore parts of it throughout development. The promises associated with our sexual identities are complex, the shame that sometimes comes from noticing and testing those promises is one of the things that draws people to kink, bondage, and so-called “alternative” experiences. I am one of those people.

During my work, most people come to me to find new ways to interact sexually, intimately, personally. Some are merely interested in the aesthetics of the practice; others come to learn the engineering aspect of ropes and the patterns involved. A small few want to question the whole machinery of a society that relates to itself and within itself as if it were a stock exchange, motivated by gain, a desire for more and more. This economic growth model approach to how we see intimacy and intimate relationships reigns unquestioned, normalized, unnoticed, like the promises we have had installed via our identities. To undermine its authority, we must find ways to approach each other outside the realm of the usual, capitalistic currencies of relationships. In other words, how can we relate intimately with each other without the assumption of accumulation, possession, self-finding, and personal growth? As an educator, one method is to avoid the terminology as well as the practices and tools that would perpetuate it, but this concept is so insidious that it is difficult for me to manoeuvre that thicket of language.

“Language is the only problem that can only be approached through itself”—as a university friend once said, in a pub, half drunk, in a bid to overthrow my (at the time) positivistic worldview (which has since dramatically changed into a poststructuralist one). Though that comment stuck with me, I must credit Derrida, Barthes, Bachelard, Bataille, and others with shifting my thinking, allowing me to find a point of attachment for my skepticism. But my inebriated friend was right—language is suspect, compromised, and it deserves our skepticism. My standard departure when I become skeptical of a term is to look, not too rigidly, into its etymology—to make myself familiar with the traces of a term, to become intimate with it. I am not looking for an origin in that sense but for a motivation, rather, a movement of the term or concept I am interested in.

To be intimate with someone is nothing but that: to make oneself familiar with them. The Latin intimare indicates, etymologically, this already. Over twelve years of teaching an intimate practice such as rope bondage, I have encountered a significant problem in this context. That which is familiar is considered close and it is this closeness, this proximity that seems to be widely understood as a precondition for the ability of making oneself familiar with one another. One could say that a very specific closeness to the subject is necessary, and any intimacy ceases to exist beyond a mysterious, undefined and yet demanded distance. This understanding of closeness as a precondition for intimacy is problematic on many levels, as it presumes not only so-called “able bodies” who can move closer to each other without barriers but also a natural hegemony of romantic love with its very specific codes and prescriptions of desire.

What if we take the call to make ourselves familiar with something or someone more literally and situate it in a seemingly different field of human endeavour? What if we looked at how a significant part of humanity, for the past four centuries at least, has been trying to explain the natural world and its phenomena? The cultural product of science as a practice of facing the world and how that world works is, too, a way of making oneself familiar with something. Scientists of all kinds and in different fields seek to make themselves familiar with what they observe without necessarily being close to it.

As much as science varies in terms of topics, fields, and methodologies, it still has, amongst other shared traits, one thing in common that is of utmost interest for me, and that commonality is what separates it from what we call technology: “Unpredictability is in the nature of the scientific enterprise. If what is to be found is really new, then it is by definition unknown in advance…”, writes Jacob in The Possible and the Actual. According to the historian and philosopher Rheinberger, science differs from technology insofar as the former arranges technical things such that they produce questions whereas the latter arranges technical things to get predetermined outcomes. In other words, a major function of science is to surprise us and the main justification for technology is to soothe us. Technical things are things we know, things whose behaviours we can predict. Both science and technology use technical things, often even the same ones. The crucial difference here is not the choice of them but rather the arrangement of those technical things that enables a behaviour that we might not have known in advance or that even surprises us, one that makes us utter, “How did it end up like this?”—in other words, the intent of science is to be surprised, to more or less stumble into the unknown. To be intimate with one’s subject of research is nothing new in science. Any scientist asked would likely talk about their field in a way that is no different to a romantic relationship.

Equipped with this understanding of how we inquire about the world, I suggest we look at how we approach one another intimately in a similar way. The scientific field I originally come from, physics, provides another tool that proved useful in my attempt to view intimacy scientifically. At least since the emergence of current interpretations of quantum mechanics, which is the realm of atomic and subatomic systems, the sciences have started to acknowledge that their purpose is not an ever-increasing description of the nature around and within us but rather that sciences create and describe models of which we cannot grasp in principle. We create models of basically everything, from ferromagnetism (“Ising” model) to the atom (“Bohr” model) to the entire universe (“inflation” model). These models are based on and nurtured by our fantasies, our desires, our wish and will to understand, but they remain exactly that: models. One reason for this principle is that the systems we observe are never independent from our observations. The way we look at a system changes it automatically, though we have a choice of what type of observations we make. Applying this principle to what I would like to call scientific intimacy, to be intimate with someone in the sense of making oneself familiar with them not only means to get to know someone else but also to get to know oneself in relation to them, as it is not possible to observe without affecting, nor is it desirable in questions of intimacy to affect without interacting. It is always and necessarily oneself who observes the other, which means that we see the other through our own eyes—that is, not through or with someone else’s.

Like in science, the models that we create of the other person, of the one we are intimate with, are also always situated at the crossroads of technical abilities. In physics, historically, it was simply impossible to ask quantum mechanical questions before the science had enough technical things to push into the realm of the subatomic world.

Things that are surprises always have the potential to become technical, but the other direction can be true, too. Things that we once believed fully understood can exhibit a completely unpredicted behaviour if they are placed in a new arrangement. We need those technical things to be relatively stable though to be surprised; to be able to make ourselves familiar with the system that we observe and that we want to understand. But we shouldn’t be disappointed if it is a technical thing, we ought to know that suddenly becomes the surprise.

Jumping back to making ourselves familiar with one another, the technical things can be as simple as the distance between one another, the choice of where to touch the other at first. But they can be complex, too. An intricate pattern in rope bondage, for example, that forces every limb, every finger of the other in a particular position is also a technical thing that, once understood, can be arranged together with other technical things such as a kiss or a smile. I personally found it hard at first to identify technical things before I had found the language of a deconstructed intimacy.

In a scientific intimacy, we might do something that exhibits our own vulnerability instead of constantly asking for the openness of the other. The technical things of intimacy are the ones we know individually but are completely and utterly in the dark about how they will behave when we arrange them in ways we are not used to. The technical things of a scientific intimacy are almost never not obscure or hidden. They are in plain sight and available and even practised, but their arrangement in novel and interesting formations has been restricted by societal norms and so we feel like we can’t use them in any other way. The opposite is true; every encounter, every touch, every kiss can be arranged in a way that it asks rather than tells. Those questions are not those of a false shyness but rather about who the other is. To be intimate with someone is, in this sense, a genuine interest in the other person and to be moved by them.

What we learn from a scientific intimacy is more than just another way of looking at the term “intimacy” itself but to look away from that obscure, meaningless construct of intimacy as merely being close to one another. It is an invitation to take the term literally and with it a whole machinery of possibilities. To view intimacy scientifically—that is, to look at how science makes itself familiar with the world—means first and foremost to not assume in advance who the other is but to experiment and to be surprised. It means that we might find properties of one another that we hadn’t anticipated. It also entails the possibility of finding out new things about ourselves, for we might be surprised about how we perceive one another from an ever-changing perspective.

My year in researching intimacy has brought me to the point at which I genuinely believe that our common understanding of intimacy is fraught. In rope bondage, practitioners all over the world equate closeness with an intimate, connective way of tying—whereas styles that exhibit a larger distance are often seen as disconnected or tormenting, for better or worse, in being that far apart. I see individuals entering any kind of intimacy as some form of quid pro quo at best and personal gain at worst. Intimacy seems to be an exploitative endeavour that understands closeness as a warming room for the self rather than a chance to discover. We seem to use intimacy as a tool to calm and comfort ourselves.

A scientific intimacy instead shows nothing of those self-soothing properties. It makes us uncomfortable; it allows us to question ourselves and how we relate to each other.

By (re-)arranging the technical things, we might be able to get to know new and exciting sides of one another. Those (re-)arrangements can be, just like science itself is for Rheinberger, a factory of surprises, a machine that creates futures. Let us allow for an intimacy that is exciting—an intimacy that bears the potential of getting to know each other in totally different and unexpected ways.