In High Femme Camp Antics, a 2020 essay for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Jenny Fran Davis combined her own romantic games of seduction and allure—of wooing and being wooed—with references to gay films, theory and novels; writing about a model of lesbian femininity that is both enthralled and ensnared by a commitment to being desired. Davis wrote: “Like all antics, the game flops because of its own unwieldiness, its own excess of desire, its own desire so big and raw and exposed that it can’t be satiated, but instead must get performed.”

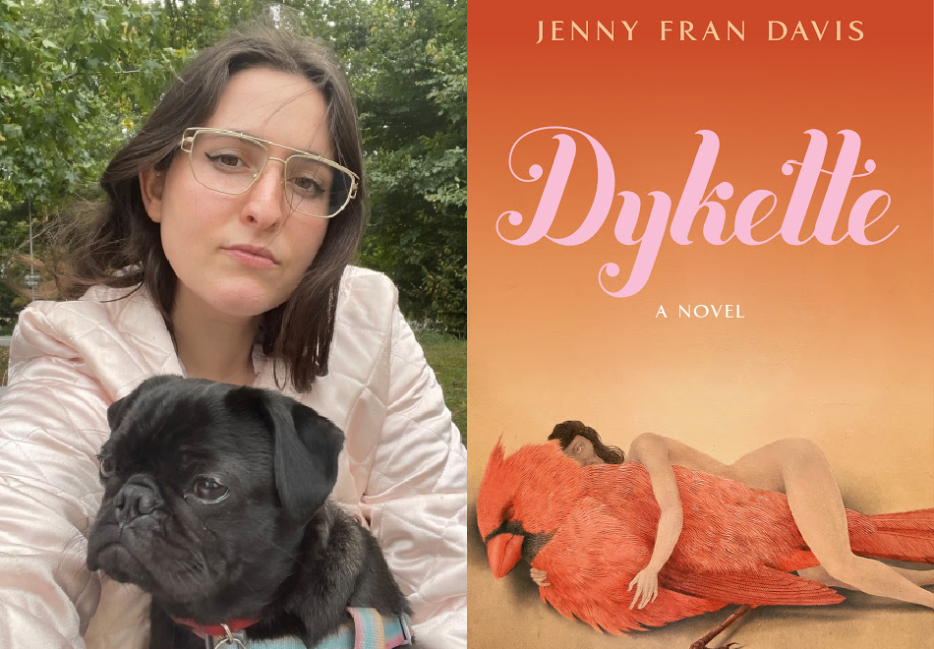

In Dykette (Henry Holt), her second novel, Davis shows up with ribbons, bows and a delightfully bitchy register to tell a story of the satiation and neglect involved in the modulating rhythm of desire; about the magic and frustration of the games we play in love. Through Dykette’s characters and their relationships, Davis frolics in the tantalizing possibility that we hope for and find in our stories of queer love.

Dykette focuses on three queer couples: Sasha and Jesse, Lou and Darcy, and Jules and Miranda. Sasha, the novel’s quintessential dykette, or “pretty lesbian” as she puts it, is seeing Jesse, a set decorator and part-time jewellery designer, who hand-makes Sasha a pearlescent dildo with an ornamental heart at an experimental leather-crafting workshop. Jesse’s close friend Lou owns a home goods store, which “can’t keep up with the demand for cutting boards,” and in Sasha’s presence, plays up their “chivalrous butch persona.” Lou is seeing Darcy, Sasha’s foil, a gay it-girl who performs from a sauna, live on Instagram, a reimagination of a viral essay that Sasha wrote. And then there’s the final, older couple: Jules is a successful news host; Miranda a psychotherapist with a podcast called Two Bad Therapists. For Christmas, everyone has converged at Jules and Miranda’s house upstate.

Like a good prestige dramedy, Dykette elevates the banal aspects of daily life: going to the grocery store, checking Instagram, trying to look cute—what Davis calls her “little gay world.” Much of this has to do with the novel’s tone—gossipy, judgmental, knowingly too serious. Jesse texts Sasha: “Can you say what you want without all the histrionics?” Things under observation very quickly become symbols; become a meme shared between characters. Sylvie, one of Sasha’s friends, texts her drunk: “You want every tote bag to be a purse!”

I spoke to Davis over the phone from her home in New York. We talked about humour, miscommunication and desire. At the heart of our conversation—and of Dykette—is Davis’s thoughtful reflections on the magic, profoundness and fun of our desires for ourselves, our relationships and how we want to be desired; about how silly but also how totally serious our identities and wants are.

~

Thea McLachlan: You refer a lot, in Dykette, to brands and what people are wearing: how the objects that they have and their consumer purchases represent something about their identity. Is that consistent with how you see the world, or does that just intrigue you?

Jenny Fran Davis: It’s always seemed really central to building a world. I’ve read amazing works of fiction that don’t name any brands or describe anyone’s outfit, but to me, in my brain, those things are really central to how I see people construct their own identities and build their own personal worlds around them. Something I was thinking about while writing this book is the quote-unquote literary novel and attempting a sort of anti-literary move of describing outfits and describing what people are buying; treating all the frivolous objects that constitute someone’s life and material world with seriousness and letting them become consequential objects in the book.

As opposed to, like, a hysterical dumping of objects as a way to create a scene.

In my own experience and observation, people really feel quite strongly about the things they own and the things they want to own and the things they used to own and don’t anymore. And there’s a whole emotional world around each of these objects. I’ve tried not to include any objects that don’t have strong emotional strings attached. I found that was a cool way for me to characterize people and access the characters’ emotions and desires through these material things.

There’s almost a parody of that—of the modern creative person. You walk around their apartment and they’re like, “Yeah here’s this thing from my trip to Egypt and oh my god this is this rug. It’s from the 1930s and it means so much to me. My boyfriend gave it to me.”

There’s a way in which peoples’ attachment to their things feels really genuine and sincere, but there’s also a way that these objects are used as shorthand to construct an identity or a self. That’s really interesting to me: How are these objects meant to read to other people? It’s not just how the characters feel about these things. It’s how they are using these things to get other people to think about them.

Do you think pursuit of authenticity is a trap? Is it all just a game where we are trying to reference things?

It’s always been so interesting to me, both the difference between sincerity and sarcasm, and also whether the pursuit of authenticity is worthwhile. Is it all just a game or a trap? Is that pursuit really worth spending time on?

Right, like what does it serve?

Why be an authentic person? Who does that serve? What does that signal? Versus being a performative person, or a campy person, or a dramatic, hysterical, sarcastic person?

You touch on that in the novel. There’s an exchange between Sasha and Sylvie where Sylvie is like: part of my appeal is that I am fake. That’s my charm. I’m proudly my inauthentic self. What’s boring about Darcy is that she is just herself.

I think in many ways this book is a love letter to fake, artificial, painted, modified, distorted people. I’ve always been way more drawn to people who seem like they are hiding something, or what they say they are isn’t really who they are. People who have undergone massive transformation in their lives are also fascinating to me. To be authentic at one point in your life isn’t necessarily to be authentic at another point in your life.

Another core aspect of Dykette is what is lost and gained in miscommunication and misrecognition. You use references that communicate different things to different audiences. Part of the joke is that not everyone is going to get it. Could you unpack how you think about humour and how it connects to miscommunication in your novel?

A big focus of the book is insiders and outsiders, especially within queer communities. Who is going to get it and who is not going to get it? Often the funniest things are things that not everyone gets, or only a super niche part of the world will understand. I wrestled with that a lot, especially because already it’s such a weird gay book. At times I truly wasn’t sure if it was successful. I made peace with the hyper-specificity of the book and maybe the hyper-specificity of the book’s humour too, because I couldn’t find a way to make it what I wanted it to be and also to make sure—in this manic way—that everyone would find it funny and get every reference.

Once I decided that, I started to really lean into the specificity. I wanted to be open to a world in which someone could read it and not get it, but still get a lot out of it. I wanted to invite a possibility where the book could open up curiosity and provide pleasure and joy to a reader, even someone who is not from this world.

At some level, that is what every novel does. There is always a hyper-specificity. It’s just less obvious when it comes from a more dominant culture or community.

True, there are plenty of books that I feel are super commercial and supposed to appeal to everyone and I don’t think they are funny at all. They are still hyper-specific. They are just hyper-specific to a more dominant cultural narrative. But there is so much that I don’t connect to at all in those books. I still read them though, and I often find them pleasurable because they totally do the trick of transporting me to another world.

In Dykette, you elevate gamesmanship—the push and pull of courtship—from something that people tend to decry, like: “I won’t text him back but only because I have to,” or, “why can’t she just be straight up with me,” to something that is useful and fundamental to the expression of desire. I was wondering if you could explore what function these games serve in relationships?

I love the word gamesmanship. It feels like an art. It is an art form, like seduction and conveying desire and withholding desire or withholding the knowledge of desire, in the way that art elevates the mundane frustrations and disappointments of daily life. I think the game of seduction and courtship—when handled with respect and the knowledge that the game can be called off if it becomes intolerable—provides a thrilling edge to the boring reality of most peoples’ daily lived experience. Which is another way of saying: it’s really fun and enjoyable. That is something that is maybe hyper-specific to me and relationships that I’ve had, and maybe the characters in the book by extension, but I don’t think it is.

It’s not a question of whether games are pure performance or pure expressions of feeling and desire. They sort of merge both of those things in a really interesting way. What you want is simply what you want, and the strategy to get what you want is itself a performance of desire. I’m thinking about the conceit of a game. Games have rules. Games have players. There’s a container. This appears in Dykette when Jesse and Sasha are talking about how their “Can I Come Inside” game does in fact resemble a game of soccer. That was really interesting to me to write because the reason a game is fun is also because of its structure and its rules and its form. The form of a game of seduction also has something that is really pleasing or comforting to Sasha, because there’s a method. Method is really interesting in terms of containing desire and containing emotion, which is something she thinks a lot about and struggles with.

Reading Dykette I was left questioning: Is the point that the games come to an end? You have that bit where you quote from Masculine/Feminine … [1]

Yeah, there is that line, something like, “he’s trapped in his performance of the masculine. She’s trapped in her performance of the feminine. Why can’t they call the game off?”

Exactly.

I think that’s the crisis point of the book: How do you transition out of a game? How do you stop playing the game and start playing real life? I think that’s the unresolved question that we come to. It’s not immediately possible for the characters in the book to do that. I don’t know how it’s done. That’s not something that my personal life experiences have shown me yet.

That’s a shame.

I wonder if that’s something that other people have experienced? Starting a game is great and playing a game is often great. But playing it can become intolerable. [There’s] that moment when Jesse and Sasha are having their massive fight where they can’t understand each other, and suddenly they are not playing the same game; the rules have changed, and we do see this absolute crisis moment. It’s a crisis of language. It’s a crisis of form. It’s a crisis of the actual material of their relationship to each other.

Partly what intrigued me in Dykette is seeing gender, or these notions of butch and femme and top and bottom, as being continually useful and fun and magical terms that enhance your life. They connect you to a history and to all these structures and funny dances that you get to play in your life, rather than how these issues are sometimes characterized: you play your game and then you’re happy and the game is over.

Identifying as anything, really, is like a magic connection to the past and to the future. It narrativizes your life in a lot of ways. It provides real comfort, real security. Those things are perfectly real and they’re perfectly legitimate and I think the magic of them is a little scary because they are not always as stable or permanent as we would like them to be.

There’s that funny bit in Dykette where Jesse is jokingly describing different lesbians in terms of the milk that they’d be. Sometimes in contemporary queer culture, people use butch and femme in a similar way. Like, “that’s so femme of me that I like having a glass of wine.” It’s interesting seeing these terms as both trivial and silly and fundamental.

It’s interesting in both the milk moment you reference and also the example of “oh, liking this wine is so femme of me.” They are both consumer choices. So much of how we construct ourselves and these identities that we hold really dear are impossible to disentangle from buying and having stuff. I find real joy and pleasure in clothes and things. I also sometimes wonder if I could possibly disentangle who I think I am from the literal material of my life: what I’ve bought and what I want to buy.

You don’t talk about astrology very much. I wondered if that was deliberate because in normal contemporary gay life it would be brought up more. People would say things like “I’m a Leo, that’s why I did that.” Instead, you replace it with terms like butch and femme.

I think it was [deliberate]. Maybe born out of self-consciousness about being cliché. I feel a little bit of anxiety about using those super, super obvious tropes of queer life—not that my friends and I don’t talk about astrology. We talk about it a normal gay amount, which is probably, like, a lot. It’s probably half that I feel self-conscious about being a cliché, and the other half is that in more recent years, I’ve lost interest in astrology a little bit. I have been more fixated on the butch/femme stuff, and how people describe their gender. That’s a more interesting question for this particular group of people.

The novel is set during a Christmas season that has a spiritual gap to it. No one seems very meaningfully religious or invested in the non-material or non-gay world. They just buy things and think about how gay they are.

Yeah, exactly: there’s a spiritual gap or hollowness at the centre and the only belief system is stuff and gender.

The novel is called Dykette––a “pretty lesbian” as Sasha defines it. Could you unpack what the term means to you?

The best way I can describe dykette is as a dyke or lesbian with frills and ruffles and bows. To me that does feel like the best way to put it because it feels aesthetic and decorative; both new and old. It feels both jarring and surprising, but also hopefully recognizable or familiar.

It’s a term that just came to me without much fanfare and then seemed like the only logical title for the book.

You have this quote: “Sasha now wanted to believe that you could be domestic and boring in a way that was less trad wife and more cozily basic.” What parallels and differences are there between the performance of femininity that you focus on in your novel of femme lesbians and the bimbo, trad revival by straight women. Is there an alliance there? Are they just totally different experiences with similar outfits?

I think there’s probably an alliance. No one lives in a cultural vacuum. We all see and hear what other women are doing on the internet and in real life. In my experience, I don’t really feel so aligned with the straighter-seeming bimbo thing, and I also think there’s a pretty big difference between the bimbo and the trad wife stuff. The trad wife stuff is pretty scary and conservative, but I also think a lot of it is really fun and funny.

Whenever I come across trad wife videos, there is something there that is like, wow, this is compelling. I don’t know why it’s so compelling to me. The bimbo stuff versus the trad stuff is where I see more alliance between a high femme, over-the-top, exaggerated femininity and the bimbo as the figure who is loving and amazingly campy and exaggerated: the Elle Woods figure. I definitely see a lot of cross conversation between those two.

In one of the scenes, where the couples are in the sauna, Sasha describes the other characters as “small tit people.” She says, “at the end of the day that was the biggest difference among them.” In the novel, your characters are relating at the level of these frameworks about femme and butch, but they’re also relating in a bodily way. How do you think the physical limits of the body relate to these other structural concepts?

Sasha feels really, really obsessed with the body. She definitely dissociates a lot, but I think, at the end of the day, she focuses a lot on her body. She thinks about how she looks and she scrutinizes other women to compare herself. That feels to me like neither right or wrong or good or bad. It just feels like an honest depiction of the character.

It was important to me to always have the narrative and the world be presented not just through the mind but also through Sasha’s physical body. Her fixation on boobs—both her own and other peoples’—it’s just something she’s really obsessed with. I also think there’s a way in which her fixation is irrelevant at a certain point. I would hope the reader realizes that fixation is communicating something else that she doesn’t quite know how to express.

When I go and get my laser done, I’m often comforted by seeing cisgender women strive for a very particular kind of femininity and womanhood through cosmetic procedures that are similar to my own. A few times in Dykette, your characters touch on that thought process. Do you think there’s a political or intellectual usefulness in bringing together these different experiences around the changes we want to make to our body? Around the shared bodily discomforts between trans and cis people?

It is something that I was very conscious of when writing those scenes where the characters, who are largely cis, express things that they hate about themselves and might want to change cosmetically. I’m really interested in the shapes that our physical forms make and how much space our bodies take up. I have found that these are concerns shared by everyone that I know; by all my friends, cis and trans. It’s certainly not the same, but I think it’s interesting to see the variety of ways that people find more peace and euphoria in altering part of their bodies.

For everyone on earth with a body, there is an interplay between how our bodies literally look, how we feel they look, and how we want them to look. It’s not that everyone experiences them to the same degree, or that there’s the same political strife with the expression and pursuit of gender dysphoria. All of these things are experienced differently. But to a certain extent they are universal and that’s something that I’m really interested in.

You quote, at the start, The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions by Larry Mitchell. In doing so, I felt that immediately you placed your novel within a broader queer canon. How important is that canon for you as a writer?

Incredibly important. I wouldn’t know what to do with myself or what to write or how to write without it, without having read so many works from the more distant and recent past. It’s essential to my process and how I think about this book.

[1] By Betty and Theodore Roszak: “She is stifling under the triviality of her femininity. The world is groaning beneath the terrors of his masculinity … How do we call off the game?”