Between worn arms, near the dark stove,

Orange ears twitching, weaving cat dreams;

Sawdust-tailed beggar, warm friend to all,

To be again graced, the scarred seat waits

— “Red,” by Gene Hall, 1995

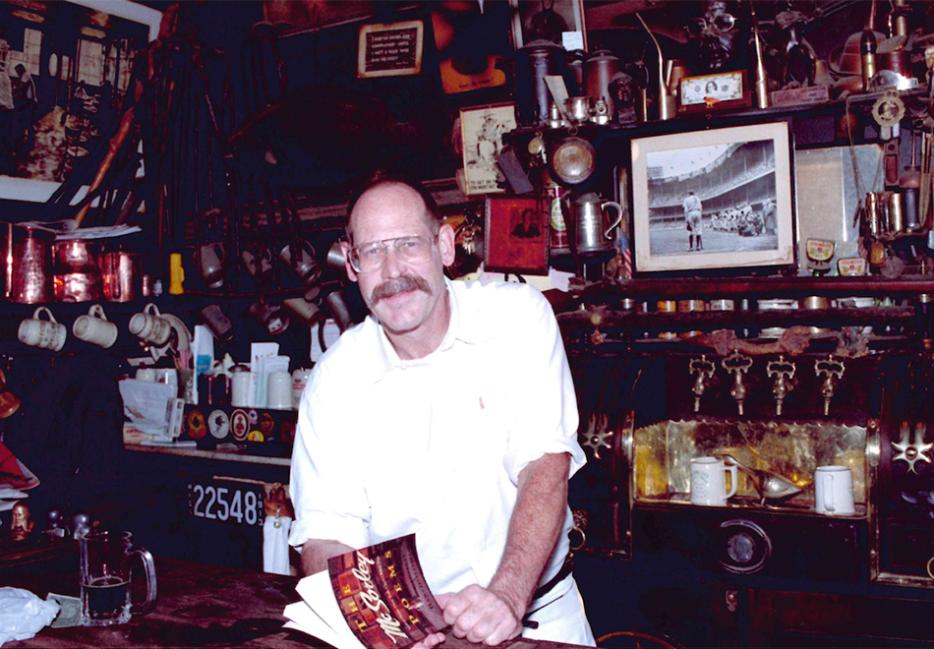

McSorley’s Old Ale House, the Manhattan landmark where my father has tended bar since 1972, has always attracted poets, but my favorite verse about the pub wasn’t written by any of the heralded bards who drank there over the years. Not the E. E. Cummings one that begins “I was sitting in mcsorley’s. / Outside it was New York and beautifully snowing. / Inside snug and evil.” Not Reuel Denney’s “McSorley’s Bar,” which contains a couplet whose beauty never fails to leave me gobsmacked: “The grey-haired men considered from their chairs / How time is emptied like a single ale.” Nothing by Dylan Thomas, who never published a poem about the bar but who drank there often enough to get eighty-sixed once upon a time. Not Woody Guthrie, a poet of sorts, who visited McSorley’s in 1943, when LIFE magazine photographed him strumming his guitar for a group of workingmen huddled over mugs of ale in the front room. And not Joseph Mitchell, whose New Yorker prose about the bar carried the simple beauty of poetry and perhaps best captured the essence of McSorley’s.

The poem that has always sent me reeling with joy and heartbreak and nostalgia wasn’t published anywhere, and it was written by Gene Hall, a McSorley’s character best known for fixing anything that broke inside the bar with gaffer’s tape. Clocks, chairs, typewriters—it didn’t matter. Tape was the answer. Gene was a retired member of the merchant marine who lived in one of the apartments above McSorley’s. During the couple of decades he spent at 15 East Seventh Street, Gene functioned as a quick-fix handyman who could be called downstairs at a moment’s notice to patch up minor malfunctions around the bar. Perhaps as a testament to the practical skills he picked up during years at sea, or maybe because it took a full-blown catastrophe to get anyone at McSorley’s to call a professional plumber or electrician, Gene’s short-term solutions often became semipermanent. Gene was quiet—it’s easy for me to recall his black mustache and dark bottle-cap glasses, but I can’t remember speaking to him once during my childhood, when my father would bring me to work on Saturday mornings. But my father and the other bartenders I looked up to talked about Gene with a measure of reverence that made it clear he wasn’t just another local screwball who hung around the bar to pick up odd jobs. And even if Gene and I never shared a face-to-face connection, I felt like he was whispering in my ear every time I read the poem he wrote in memory of Sawdust, the McSorley’s cat I grew up with.

“Red” is a four-line poem about a bar cat, an orange tabby named both Sawdust and Red. My dad and I called him Sawdust because his fur reminded us of the wood chips the waiters spread across McSorley’s floor every morning. Some of the old timers preferred a simpler nod to his color: Red. He was the last great cat to spend his entire life—1985 to 1995—at the bar. I grew up dangling strips of cold-cut ham and turkey for him to claw out of the air, then sitting beside him and petting him in his favorite spot, a chair behind the potbelly stove. He was fearless and outgoing—my father could set a mug of water on the bar and Sawdust would leap up and start lapping it up between amazed customers. He was daring—my dad loved to tell the story of the time Sawdust sprang from a hidden, dark corner of the bar to sink his claws into a banker’s thigh, right in the spot where a roach had passed moments before. Mischievous and tender and ever ready for some new friend to scratch behind his ears, Sawdust was adored by pretty much every person who met him, and he died too soon.

When my father returned from work one Friday evening in 1995 and told me that Sawdust had developed some form of feline cancer and had to be put to sleep, I remember thinking it was impossible. He was only ten. At home, my family’s neurotic house cat Bismarck (obtained through a McSorley’s cat litter and distant cousins with Sawdust) was ancient, nasty, and showed no signs of slowing down. Why’d we have to lose Sawdust?

Gene must have felt the same way, because he typed four timeless lines about the cat, which were then framed and hung on the wall behind the stove, just above the chair where Sawdust loved to sleep. The final image in Gene’s poem, of the empty seat, marked by Sawdust’s scratches and awaiting an impossible return, brings the image of the cat coiled in slumber straight to the front of my mind, as if I’m seeing it in real life. And at the same time, it reminds me how forevermore I’ll see Sawdust only in my memories.

I love this poem because it connects me to a specific time in my bar upbringing. If not for that overpowering bit of nostalgia, though, I’d choose any of my father’s poems as the most vital bits of McSorley’s verse ever put down on paper.

*

My father grew up in Euclid, Ohio, and moved to New York City in 1967, when he was twenty-two. He got drunk in McSorley’s on his first night in Manhattan and wound up moving into an apartment above the bar in 1970, which led to him working there a couple years later. His first decade in the city was defined by books and booze. He arrived in New York a heavy drinker, the habit passed down from an abusive alcoholic father, and before long my dad settled into a routine of polishing off one quart bottle of cheap vodka or brandy per day, plus a round or two of McSorley’s ale whenever he passed through the bar.

He kept himself together enough to hold down his shifts at McSorley’s and to enroll in the MFA creative writing program at City College, whose faculty back then included Adrienne Rich, Joseph Heller, and the two authors in charge of my father’s seminars, Anthony Burgess and Kurt Vonnegut Jr. After nights of slinging ale and cheddar plates served with raw onions and a sleeve of Saltines, he’d trudge upstairs to his apartment and peck away at his typewriter until five or six in the morning, fueling himself with sips of Tab and brandy. His first completed manuscript was a 900-page epic—a father-son coming-of-age tale mixed with a spy thriller and framed by the Jason and the Argonauts myth. Then, my father attempted a stream-of-consciousness novel written from the point of view of two brain-damaged stroke survivors that, in the style of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Her, contained no punctuation. His next project was less formally daring but still plenty imaginative: a futuristic dystopia in which New York is overrun by giant, man-eating rats.

None of my father’s manuscripts sold, and as years passed his ratio of time spent drinking versus time spent writing tipped heavily toward getting soused. After spending a drunken night in May 1975 standing on his fire escape, looking down at the sidewalk in front of McSorley’s, and thinking he should throw himself upon it, my dad decided to get clean. He began attending twelve-step meetings and gave up writing, which was tied together with his romanticized self-image as a depressive, alcoholic writer.

In 1976, about a year after my father got sober, he traveled to Vancouver, British Columbia, to visit Cates Park, where Malcolm Lowry wrote much of Under the Volcano. It was an alcoholic’s final pilgrimage, my dad’s chance to pay his last respects to this patron saint of drunkards. When my father was drinking, Lowry had provided him with a fatalistic ideal of how addiction, even at its most destructive, could produce something transcendent. Sure, Lowry drank himself to death. And by most accounts, he sank into abject misery as his alcoholism progressed and gradually overwhelmed his literary talent. But along the way, he wrote Under the Volcano. Was that not worth it?

When my father was depressed and drinking, the answer to that question—fucking A it’s worth it!—seemed clear. When he saw no way out, when he assumed he’d just keep boozing till he died—the dead alcoholic son of a dead alcoholic father—that inevitability could even feel inspiring: I know I’m screwed. My dad fucked me up as a kid and I’ve only fucked myself up worse. But while I’m around, maybe I can create something that matters.

So when my father stood along a path named Malcolm Lowry Walk on a raw and gray Pacific Northwest afternoon and looked out on Vancouver Harbour, not only was he saying goodbye to the vodka-infused self-hatred that he’d carried throughout his adult life, but he was also walking away from the writerly ambition that had been his sense of purpose in those years. That creative impulse had kept him from being just another Bowery wino, but the practice of writing had become too tangled with the habit of drinking for my father to give up one and continue the other. To have a shot at a better life, he had to quit both.

So he wrapped rubber bands around his manuscripts, shoved them inside leather portfolios, and shoved those inside shoe boxes: the Argonautica novel; the punctuation-less screed about bedridden stroke victims trapped in their own minds; the sci-fi tale of New York terrorized by two-hundred-pound rats. He locked them away in file cabinets and put his energy toward staying clean, working at McSorley’s, and devoting himself to family life. He married my mom in 1979 and they had me three years later.Besides love notes to my mother and birthday poems for me, my father gave up creative writing for the better part of two decades.

But he never let go of the written word. When I was young, the first thing my friends would say upon visiting our apartment was always, “You have a lot of books.” My mother, who’d left the hotel and corporate kitchens she had cooked in before I was born to teach hospitality management and culinary arts at a CUNY campus in downtown Brooklyn, had a wall of cookbooks opposite our front door. Each room in our place had its own mammoth bookcase—a shelf for my father’s accumulated dictionaries, musty Modern Library editions of Crime and Punishment and Moby-Dick with their onionskin-thin pages, a corner filled with novels and essays and letters by Lowry, Vonnegut, Norman Mailer, and other practitioners of the virtuosic, manly prose my father admired in the seventies. Even the TV “entertainment center” in our living room was more bookcase than anything else. The floor-to-ceiling complex of shelves and cabinets was entirely stuffed with books, except for a small, square space in the middle to house a television set.

Although I don’t remember seeing my father sit down at a typewriter when I was a kid, I understood that he’d been a writer, saw his creative writing MFA diploma hanging on our wall, and heard about his unpublished novels. He tried to build the foundation of a literary sensibility in me, insisting that we spend Sunday mornings reading Huckleberry Finn aloud to each other as soon as I got far enough in school to speak full sentences. It didn’t work. Twain time might as well have been Sunday school to me, and until my mid-teens I pretty much always chose going to the movies with my mom or playing pickup basketball over cracking open a book.

At times, I could even be contemptuous of my father’s passion for reading and writing. I have no clue what motivated this occasional nastiness, other than the wanton tantrums of adolescence and the impulse to lash out at one’s parents. It was during one of these moments when I committed what I now think of as the most shameful act of my youth.

I was nine or ten years old. It was a Sunday afternoon and my parents took me to a diner a few blocks north of our apartment for lunch. I can’t remember what, if anything, made me angry that day. Probably, my dad had called me out for getting outhustled on a rebound during a rec-league basketball game that morning. Late in the meal, as I picked over my remaining french fries and avoided a mayonnaise-oozing cup of coleslaw, my mother asked me about a recent playdate with a friend from elementary school, inadvertently hitting a nerve with my father.

After the playdate, when my dad had come to pick me up from the other family’s apartment, my friend’s mom gushed to him about friends of theirs whose son would soon publish his first book. The kid was the same age as me, and his forthcoming book was some cutesy how-to gimmick about growing up in New York from the point of view of a real third grader. The notion drove my dad crazy. The child author’s family was wealthy and connected: address on Park Avenue, Dad in finance, Mom a high-powered media somebody, attending the prestigious and completely unaffordable Dalton School. He was the kind of kid whose parents dress him up in Brooks Brothers suits—and who actually likes it. He was the type of character guaranteed to rankle my father’s working-class sensibility. And because this kid’s family knew everybody who was anybody, this nine-year-old was getting a chance to achieve a dream that had eluded my father.

“Next time Rafe goes over there you better pick him up,” he told my mom. “I don’t think I can take that again.”

“Why?” she asked.

“Well, I walked up there and the girl’s mom wouldn’t stop jabbering about some other kid they know who’s so brilliant and who’s going to publish a book. Give me a break. It’s just some rich kid whose parents pulled strings.”

Even at that young age, I felt aligned with my father’s sense of class conflict. I’d never met this boy, but I didn’t like him, either. But I was still stewing over our basketball argument, so I decided to say something I knew would hurt my father: “You’re just mad because he has a book and you don’t.”

As soon as the words jumped off my tongue, I knew I’d crossed a line. My chest tightened, and I felt like a fist had risen up from my belly and lodged itself in my throat. I stared down at the paper place mat in front of me, filled with little square ads for neighborhood dry cleaners and bakeries. I couldn’t look up at my dad, who didn’t even respond. He didn’t show anger or sadness or disappointment, and that made me curse myself even harder. Why the hell did I say that? Why would I call my father, whom I loved and just about worshipped, a failure? I didn’t even believe what I’d said, but I said it because I wanted to stick it to him. He probably doesn’t even remember that moment, but now, almost twenty-five years later, I feel sick thinking about the silence around that table and the look on his face when I raised my eyes from the place mat. His face was empty—just numb. As if his only thought were, How could my son do this to me?

*

My jeers that day were especially hurtful because during those years my father had begun to consider changing careers. He was a little more than twenty years into his tenure at McSorley’s, and many of the guys he’d worked with and grown close to in the eighties had left the bar for more fulfilling lines of work. Noone gave up his front-room waiter shifts to become a college math professor; another waiter, Fuller, got hired as a manager at the flagship Barnes & Noble bookstore in Union Square; Farnan, one of my dad’s partners behind the bar, married a surgeon and moved to Connecticut; and there was Bart, my father, staying put behind the taps and wondering if he should also try something else before it was too late.

He got close. For two years, he rode the train up to Hunter College on his off days to take graduate courses in education. He earned the necessary credits for a degree, wrote his master’s thesis, and gave serious thought to becoming a high school English teacher. But he couldn’t complete the program and receive his certification without a half-year of student teaching experience, and that would require him to quit McSorley’s and spend six months working for free. He could have made it work—my mother’s City College job was secure, and because she and my father had already paid off the remainder of the mortgage she and her previous husband had taken out on our West Village apartment, my parents were carrying hardly any debt.

But the prospect of not earning for half a year made my father question how badly he wanted to run a high school English class. On one hand, he was eager to try something different and he believed he could develop into a great teacher. With his passion for the written word, his ability to read people and treat them with appropriate levels of compassion or toughness, and his bar-honed street smarts and sense of humor, he knew he had it in him. But was it worth everything he’d be forced to give up? It would take years before his teacher’s salary caught up with the money he was already taking home from McSorley’s. He’d no longer be able to work nights—a schedule that allowed him to spend time with me in the afternoon and attend nearly all my basketball games. And what if he got stuck in one of the city’s underserved and overwhelmed public high schools, forced to spend his class time maintaining order among forty or fifty rowdy, hormonal teenagers instead of teaching the work of the novelists and poets and journalists he loved?

In the end, it took two years of course work and arriving right at the edge of a decision to leave McSorley’s for my father to realize he wanted to stay at the bar. He didn’t need to change careers to find satisfaction. He just had to find a way to inject the bartender’s life with a greater sense of purpose. The solution was obvious: He had to write again.

My dad likes to say that the novels he wrote in his twenties never got published because he wasn’t sober and clearheaded enough to complete a fully realized work of fiction. That theory is as good as any, but here’s another: Those books were all some form of imitation. They didn’t really spring from my father’s experience and imagination. The reimagining of the Argonautica myth was a nod to James Joyce and Ulysses. The stroke novel was a stab at Ferlinghetti’s avant-garde formal experiments. The attack of the giant rats book is tougher to trace, but its blend of sci-fi absurdism and sense of impending doom could have been influenced by Vonnegut and Burgess, my father’s grad school instructors. My father had spent a decade working on three books, but not one of them was truly his.

It took those unrealized novels, plus a couple of decades at McSorley’s and an aborted attempt at changing careers, for my dad to finally settle into his voice—that of a wizened, slightly weary everyman bar poet. After he decided to junk the plot to become an English teacher, my father began work on The McSorley Poems.

During my last few years of high school, he was nocturnal. On Sunday, Monday, and Thursday nights, he’d arrive home from McSorley’s around 2 a.m., take a shower, and then park in front of our family’s massive desktop computer. His workstation was set up in a corner across from my bedroom, and I got used to waking up in the middle of the night and seeing the glow from his monitor creeping toward me through the crack at the bottom of my door. I’d fall back asleep to the staccato clack of his fingers on the keyboard.

He went on like this—stealing hours on the graveyard shift, writing and revising and refining between two and six in the morning—until one day I woke up before school and saw a binder on the kitchen table, right where I usually sat down to eat my cereal. I flipped it open and found an early manuscript of The McSorley Poems, by Geoffrey Bartholomew.

*

I don’t really like poetry. I blame myself, not the poets or the form. Maybe I’m too impatient, maybe I’ve got the wrong temperament, or maybe I’m just too simpleminded, but I’ve always been the kind of reader who prefers plain, straightforward writing about a subject that interests me. There may be beauty and mystery in some poetry’s broken syntax and delicate metaphors, but often, by the time I’ve decoded a line’s meaning—if I’ve decoded its meaning—my first response hews toward, “Why bother?”

But The McSorley Poems spoke to me. Feel free to chalk that up to filial piety—I was going to find a way to like the book even if my father had decided to write the entire collection in nineteenth-century Gaelic. But from the first pages of the manuscript, I found myself engaged. In every line of every poem I recognized the artifacts and characters I’d grown up around and felt them come alive with language.

The first third of the binder described various McSorley’s artifacts—the turkey wishbones that had been dangling above the taps since 1917, when a group of regulars hung them for good luck before shipping out serve in World War One; the stuffed jackalope behind the bar; Harry Houdini’s handcuffs dangling from the ceiling as if the great escape artist had been hanging there with them, freed himself, and left behind a souvenir. The middle section consisted of poems devoted to “Unsorted Regulars, Misfits, Liars, Heroes & Psychos.” The language was raw, peppered with black humor and full of tragedy—a reminder that for all the laughter and communal goodwill I associated with McSorley’s, the men and women who are drawn into the bar’s orbit typically arrive with some scars. These were my father’s people, the alcoholics and loners and deviants he made his life with, and even at their darkest, the poems shined a light on his characters’ humanity. The first stanza of his poem for a deceased former coworker named Doc Zory made me feel as if I’d finally met a figure who existed in my head as some kind of long-lost uncle:

Big Z was my old man

first Gypsy violinist

to play Carnegie Hall

Ma died young on us

so he taught me the axe

honing an edge to call shadows

until beauty was airborne

I’d hear him at wolf’s hour

that moan of catgut

barely touching

then madly bowing

wrenching their love

when he died

I joined the Navy

The plainspoken lines were a step and a half removed from prose poetry, and my father was telling the stories of a career’s worth of bar denizens. The manuscript was a history as much as it was a collection of verse, with the third and final section reaching back to portray Old John McSorley and the bar’s founding family through a blend of archival research and my father’s imagining of the emotional lives of the Irish clan that came to the United States in the 1850s and opened the bar under its original name, The Old House at Home.

He put the finishing touches on the manuscript in 2000, my senior year of high school, and gave the book a title: The McSorley Poems: Voices from New York City’s Oldest Pub. Twenty-five years after he’d earned his master’s in creative writing, my father found his voice, and it happened to be in the bar where he drank on his first night in Manhattan, back in 1967. McSorley’s cast of sad sacks and strivers was a perfect fit for my father’s storytelling poetics, filled with the pathos and hope and explosions of humor that made pub life so rich.

Adapted from Two and Two: McSorley's, My Dad, and Me by Rafe Bartholomew, published May 2017 by Little, Brown and Company.