My friend’s annual Christmas party is a death trap for my stomach. In 2014, the meatball tray was my demise. I felt the initial rumble, then the flash of pain, and I made the hurried dash to the bathroom. I texted my friend outside, telling her that I would be in here for a while. I send these texts frequently. My absence would have been noticeable—there were only two people left at the gathering: the host, and a beauty queen with looks reminiscent of Miranda Kerr.

Though her pageant days are behind her—her most recent title was Miss Global International Canada 2012—I still couldn’t help but feel totally mortified. Hunched over for what felt like an hour, but might have been only half that, I chastised myself—you can’t have diarrhea around a beauty queen! Each second that exceeded the acceptable average time to be in the bathroom felt excruciating.

Later, I reminisced about it with a fellow Irritable Bowel Syndrome-sufferer. We both came to the same conclusion: beautiful girls don’t poop. It was a sexist, absurd thing to think—and by thinking it, we had deemed ourselves ugly women with an embarrassing problem. But a part of me believes it to be true.

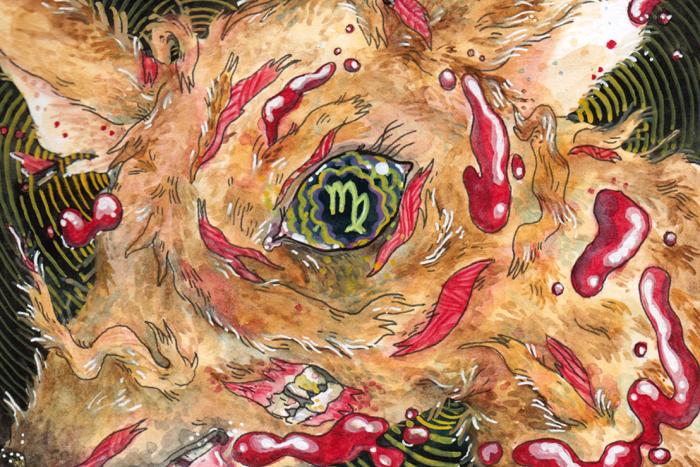

According to the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation, there are about five million Canadians suffering from IBS, and it affects more women than men. It’s estimated that between 1 in 10 and 1 in 4 worldwide have IBS. While the more graphic parts of IBS are easy enough—though, rather unpleasant—to explain, there is a social side effect to the syndrome that goes unnoticed by those who don’t have IBS, or related illnesses like Celiac disease or Inflammatory Bowel Diseases like Crohn’s. With each bout of diarrhea or constipation, nausea, and excruciating abdominal pain comes a wave of humiliation, low self-esteem, and a feeling of isolation—from the people around you, and from your own body.

There’s no real test for IBS, but rather tests that rule everything out. For me, IBS had been a lifelong problem, but I was diagnosed just last fall. Coming home from the doctor’s office, I stomped my feet up the stairs and angrily declared to my parents that I had to provide six separate stool samples from six different days.

“Use Saran Wrap,” my dad said. My father has Crohn’s disease; so naturally, he’s an expert at poop tests. We laughed as I went downstairs to grab the Saran Wrap, which I took everywhere with me around the house for over a week.

Every time I’ve had to barricade myself in a bathroom, I feel the space between my body and my femininity, between myself and the people socializing outside, grow wider and wider. I imagine them thinking of me in a pitiful way, or becoming so accustomed to my absence that they hardly even remember I was there in the first place. In the age of selfies, and empowerment, and body positivity, where does my body—diarrhea issues and all—fit in?

Historically, men have always been characterized as connected to the mind—rational and logical—while women are often viewed in relation to their body—emotional, existing for the male gaze. Many of the earliest, and most praised, philosophical writings, by thinkers such as Aristotle, Plato, and, later in history, Kant, are plagued with sexist notions about the status of women as compared to men. Often, women were written as irrational, only present in the body rather than in the mind. Traditional gender roles have often presented women as dainty, graceful, sensual; ultimately objects. It’s in this objectification that the truth has been obfuscated, but these constructs have made women self-conscious about their bodily functions, as evidenced by articles such as “The Last Office Taboo For Women: Doing Your Business At Work,” in The Daily Beast, and “7 Reasons Why Every Woman Should Poop At Work,” in Bustle.

If women without IBS are anxious about pooping at work or at a partner’s apartment, then the anxiety for those of us with IBS is undoubtedly worse. In fact, studies, such as one in the Journal of Science in Today’s World, have shown that IBS patients have lower levels of mental health. In some cases, IBS treatment has even included prescribing anti-depressants. According to the Journal of Molecular Psychiatry, IBS flare-ups can even be triggered by negative emotional states, creating a debilitating cycle.

If there’s one symptom all of us with IBS and related illness universally have, it’s powerlessness.

The stinking up of public toilets, waiting in the endless long line that is inevitable in women’s washrooms at bars and clubs, the awkward “excuse me” before you leave for a good forty minutes—it all makes for a complicated relationship with one’s body. “I think a big thing is not feeling desirable, not feeling sexy,” says 31-year-old Megan O’Neil, a business administration student studying in Cranbrook, BC. O’Neil’s IBS is on the constipation end of the spectrum, resulting in intense and painful bloating. “You know woman aren’t supposed to have pot bellies,” says O’Neil. “But I get so bloated that I feel really unattractive and I feel really unfeminine.” Most of her wardrobe is made of looser, flow-y clothes—whatever conceals the bloating the most. “Who would desire someone who’s this big bloated farting machine who stinks up the bathroom?” says O’Neil. While both O’Neil and I are aware that the idea of what a woman’s body is supposed to do or supposed to look like is part of a misogynistic social construct, we can’t help but cling to these notions. While we would never believe that another woman was unfeminine or ugly because of her IBS, we apply these harsh judgements to ourselves. Our feminist ideals and how we actually perceive ourselves are in constant contradiction with one another.

Arista Petkau, a 25-year-old sociology honours student at the University of Winnipeg, doesn’t feel like IBS is conflicting with her femininity. “Femininity is a moving target, no matter how much society wants to insist there is some universal ideal,” says Petkau, “we all define it differently.” Femininity, outside of a patriarchal mode of thinking, is an abstract idea, which means that health issues shouldn’t detract from our sense of womanhood. While I’ve always seen my IBS as this massive contradiction to my femininity, I’ve also realized that this contrast only exists because I’ve allowed someone else’s definition of femininity to define my own. Women’s bodies are constantly being defined and debated for them. What constitutes a “good body” is a set of ideals, often washed over with a facade of so-called morality, chosen by everyone but us—by male politicians, by corporations, by online trolls, etc. I know all of this, but in the midst of an IBS flare-up, when I’m all by myself in some dingy bathroom, I find myself wondering: is my body a “good body”?

Managing IBS involves a combination of over the counter drugs, dealing with stress and anxiety, and avoiding trigger foods as much as possible. And this is pricey; the probiotics I was initially buying contained 50 capsules, and came to almost $50 with tax. Almost a dollar a capsule. Some days I had to take two. Now, I’ve opted to buy probiotics from a wholesaler. I stock my purse with Pepto chewables, Imodium for emergency diarrhea cases, and some type of painkiller for those major abdominal pains that can sometimes cause me to vomit from the sheer strain of it. “There is unfortunately no single prescription for IBS,” says Dr. Wissam Hussein, a family physician practicing in Ottawa.

If there’s one symptom all of us with IBS and related illness universally have, it’s powerlessness. It’s the feeling that your body is running you, and in the most embarrassing way possible.

I’ve grappled with this feeling of powerlessness, and ugliness. I’ve felt the distance between me and my body and femininity, while people are knocking on the bathroom door asking what’s taking so long. I’ve struggled with those ugly days—not ugly because my hair and makeup was off, but because the growl of my stomach tainted my whole ensemble.

But in talking to other women, I’ve realized something important, despite all my moments of self-doubt within the walls of the washroom: beautiful girls do poop.