Ever since Gus Van Sant's Good Will Hunting introduced 1997 audiences to a beautiful but violent and appealingly damaged young man—stuck doing construction in Southie, wrestling with undiscovered genius, a metaphor for struggling young actor Matt Damon trying to be great (and sure, his buddy, cowriter, and costar Ben "Reeee-Tainer!" Affeck, too)—the "Boston" movie has become its own specific genre. It was far from the first film set in the city: throughout the short century-plus of American moviemaking, plenty of movies have taken place in Boston, with a small handful (The Verdict, Love Story, The Friends of Eddie Coyle) achieving something like greatness or notoriety, taking on icons and symbols of the city from the Catholic church to the college campus to organized crime. But Good Will Hunting was a hit, and following in its wake, there were state-wide tax breaks which meant film crews could actually afford to film in the city. The increase in Boston-based productions felt undeniable.

As film critic Lisa Rosman wrote in an essay tied to last year's release of the Johnny Depp-starring Black Mass: "It may be that the real reason Bostonians play so well on film is because they're so endearingly, charismatically foul." Rosman points out that Boston is a city with a white underclass, tied to a tortured racial history. On the phone, A.O. Scott, the New York Times film critic and the author of Better Living Through Criticism, elaborated. "The fact is Hollywood always prefers to make movies about white people, and it is more comfortable making films about white criminals than black criminals. If you wanted to find a white underclass, you can find it in Boston, Southie, Charlestown." As New York has transformed into a "safe, cool, wealthy city," according to Scott, in the ‘90s and 2000s, Hollywood still needed a location that represented the "grit and grime of the underworld." Boston fit the profile.

But there was another element: the church. Going back to the Puritans and the Salem Witch Trials, the greater Boston area was colonized by the religious, with an intensity that bears the weight of history. John F. Kennedy, the first Catholic president, was a model of the Boston Irish Catholic for the whole world. What the church provided—at least in the realms of Boston-based entertainment—was a model of good as characters did bad. After all, a gangster needs something to love, a ritual to follow. The sound of church bells, angelic children in white cloaks, priests sharing the good word, the idea that God could be reached by attending mass on Sunday. But, despite the many movies set in the city, I haven't seen a film that understands the way the church looms over Boston until this year’s Spotlight.

*

A small city that has given itself the nickname the "Hub of the Universe," Boston once coasted on its history, only to immediately lose its cultural cachet to New York. Scott (who went to school in Cambridge, but politely demurred when I asked him to "please start every reply with As a Harvard man ...") described Boston in neat terms: "In American history and its own mythology, it's both the city of Puritans and Harvard and the whole phrase Boston Brahmin. The highest reaches of the American blue blood WASP ruling class are located there, sitting on top of this tough immigrant city, with an interesting history of labor radicalism, of organized crime, of racial history. There's a lot existing side by side, and maybe just a little bit more intact than other American cities."

If I could sum up the long shadow of the church over my life, it might be with this memory of my best friend in high school mooning over her boyfriend one day: “I love Peter. I wanna fuck him!” she said. Then, as if she’d been caught, she went into a cheerleader kneel and yelped, “I love Jesus!”

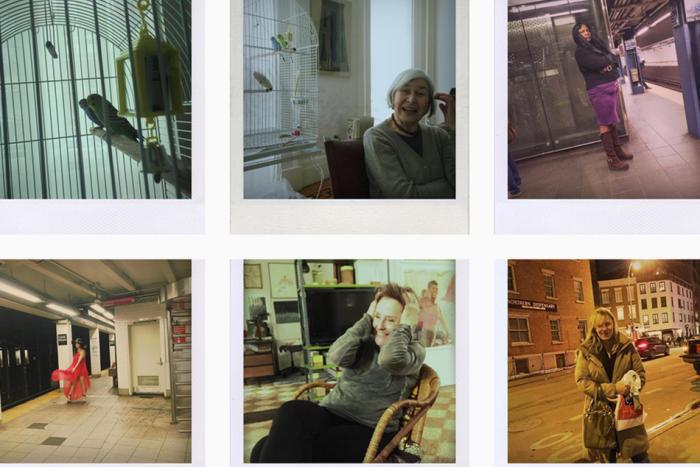

To be precise about where I come from in Boston (often shorthand for "the greater Boston area," a shorthand that carries the weight of history) and its particular, clannish peculiarities, I defer to Brian McGrory, the editor of the Boston Globe. As a metro columnist, McGrory wrote piece after piece about how our mutual hometown of Weymouth—a suburb 15 minutes from the city, best known for First Lady Abigail Adams, a now-closed shoe factory, and likable comedians Rob and Nate Corddry—was gritty and blue collar. The white-collar swells of Hingham, the picture-book-pretty town next door, were just the worst. I moved away from Boston, a place where I spent my childhood and much of my young adulthood, when I could no longer afford to live there. The only jobs were in biotech, bringing in money that was blanding out the city, turning closed churches into condos. It felt, in some ways, like an exile. Yet living away from Boston was a chance for me to see the city as it is, with its complications: a place with a painful relationship to race, clannish and full of secrets, where family and loyalty could become its own twisted vine.

I grew up with the Catholic church, attending mass every Sunday for most of my young life. I ended up going to the same Catholic high school where my mother taught, enduring theology classes about why abortion is bad, singing in the church choir at mass, clapping my hands in the shape of a cross to the beat. If I could sum up the long shadow of the church over my life, it might be with this memory of my best friend in high school mooning over her boyfriend one day: “I love Peter. I wanna fuck him!” she said. Then, as if she’d been caught, she went into a cheerleader kneel and yelped, “I love Jesus!” It took years for me to realize that liking a boy, that kissing a boy, wasn’t going to spontaneously impregnate me with the offspring of my supposed sin. Catholicism was so entwined in my daily life that I couldn’t even clearly see where it was good and where its ideology was messing with my perception.

While the Catholic church left its mark on my life early and clearly, it was harder to understand Boston’s history of racism from my suburban vantage point, through the myopia of being surrounded by people who were, on average, just like me. The greater Boston area has always been relatively segregated, with towns defined by race, religion, and class. I was too young to understand the true inciting incident that made Boston’s racism clear: the riots that broke out in Southie when the Boston Public Schools were forced to desegregate in the ‘70s. As the years wore on, I gained a greater understanding of the city’s racial divisions, but frankly, books helped me catch on far more than an errant comment by a distant relative drunk at a party, books such as Danzy Senna’s novel Caucasia, about two multiracial sisters growing up in Boston in the ‘70s. J. Anthony Lukas’ Pulitzer Prize-winning nonfiction classic, Common Ground, looms in front of me as a book I should read when the moment is right. (Contrast such publishing with filmmaking, which continues to woefully underserve these sorts of diverse Boston stories.)

*

In leaving, I may have been able to see the way that my hometown shaped me more clearly. But Boston itself was receding into the past, becoming a place of gauzy memory. Nostalgia, according to Scott, is a strong impulse: "It has a lot to do with how we think of places." It's been an odd coincidence that at the very point hometown nostalgia bloomed in my mind, the Hollywood dream factory echoed my very thoughts, coming out with film after film set in movie-Boston. There were stories about rats, kingpins, double-crossings, heists. It was during this era that Boston became synonymous with a certain type of "authentic" crime movie. Actors got to try the Boston accent on like an ill-fitting coat, and characters reached for loyalty like a state of transcendence. First, Sean Penn got Best Actor for 2003's Mystic River. Then 2006's The Departed won Best Picture. In 2007, there was Ben Affleck’s well-received directorial debut, Gone Baby Gone, and the next year, Mark Ruffalo’s addition to the tortured Southie criminal genre, What Doesn’t Kill You. Films from the late '90s such as Monument Avenue and Southie were in and out of theaters again.

This likely had everything to do with the persistence of our very own ghost: James "Whitey" Bulger, South Boston's most notorious kingpin, the second-most-wanted criminal on the FBI's list (after Osama bin Laden) during twelve out of his sixteen years on the lam. "He might be a crook, went one line of thought, but at least he was our crook," Charles McGrath wrote in The New York Times. There's been a perverse sense of hometown pride in the way that Whitey couldn't help but be referenced in the movies.

Growing up, the story of Whitey felt like an overwritten book you'd never believe: an Irish boy (from the same projects as my father) became a gangster, the sociopathic king of Southie whose brother, Billy Bulger, was the most powerful politician in the state. Two brothers, one a heel and one a prince—it's nearly Greek. Whitey controlled the drug trade in Boston, ran weapons, took and hid money, and was responsible for nineteen murders. Then the truth came out, somewhat, in a series of books written by many reporters from the Boston Globe. All this time, Whitey was also a rat, singing like a bird to FBI agent John Connolly, who was—surprise!—a neighborhood boy from Southie.

It's a weird story, with entirely too much jai alai, and it lent itself to film after film: The Departed, The Town, the documentary Whitey: The United States of America Vs. James J. Bulger, Black Mass. In all of these movies, Boston is rendered, as the Boston Globe's film critic Ty Burr wrote in a review of The Town, as "Movie Boston ... a sub-Scorsese landscape of stubbled men walking down mean Suffolk County streets that exist primarily in the minds of good pulp novelists and bad screenwriters."

Praise Saint Affleck, but it may just be that Martin Scorsese's The Departed was the best of that lot, diving into the insularity and peculiarity of a neighborhood that would birth such a monster with sharp dialogue that turned pulp cleverness into something like its own myth, birthing a faux Whitey so evil—Jack Nicholson's Frank Costello—that he'd wear a, gulp, Yankees baseball cap. Screenwriter William Monahan, who won an Oscar for his work turning the Hong Kong original Infernal Affairs into a Boston Shakespearean tragedy, confidently proclaimed that The Departed was the best Boston movie of all time in a 2010 Collider interview, saying, "the x-factor that people can't quite put their finger on is [The Departed] deals clearly with class and accent and all these things that are fundamental to Boston. It was the first time Boston was ever put accurately on screen."

Spotlight's style has been dinged as that of a TV movie, but it's exactly this claustrophobia, the dinginess, the euphemism-filled conversations with powerful men on golf courses and in their great houses, that gets across some of the rules of Boston.

Half of the authenticity in The Departed came from Mark Wahlberg's performance, a real wild-card, aggressive sort, muttering stuff about "lace curtain Irish," irrationally hating on both Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon. Most of the other performances could be transferred to other cities, no problem, but more than Nicholson’s Whitey, Wahlberg’s asshole—the smartest guy in the room, making claim to that statement by also being the biggest and funniest jerk—was our asshole.

The bulk of Boston movies feel like they do one thing well: dive into the seedy world of organized crime, maniacally focused on South Boston because of Whitey and its whiteness, the lock-step rules of families where everyone knows everyone else's business and they're all stuck on a peninsula, physically split from downtown by the highway. Yet despite the widescreen pans over Southie’s real estate, very few of these films get at the nuance that lies beyond Southie’s cramped triple-deckers and neon-lit bars. On average, these films feint at a sense of space, never to equal Good Will Hunting’s gauzy, Elliott Smith-scored interludes driving over Boston’s bridges, Will Hunting dreaming in the subway. Those scenes showed the difference between where Will Hunting was from and where he was going. Every other Boston movie just puts dopes and rats in a maze.

*

Despite film after film about Boston’s stifling presence, too locked into its clichés to actually render the city truthfully, I was pleasantly surprised by Tom McCarthy's sturdy, moving Spotlight, last year's picture about the reporters from the Boston Globe who exposed child sexual abuse in the Catholic church, crimes that went back decades and ripped through families. Spotlight should win Best Picture at the Oscars this weekend11Editors' note: It sure did. . (Unless we learn we are somehow living in a perfect world where Mad Max: Fury Road is crowned The Greatest Movie of All Time.)

Spotlight is a movie that takes place in rooms: the fluorescent-lit hovels of the Boston Globe's offices, the dark bars where deals are made, a shabby lawyer's office where a reporter sees the track marks on a former altar boy's arm. The style has been dinged as that of a TV movie, but it's exactly this claustrophobia, the dinginess, the euphemism-filled conversations with powerful men on golf courses and in their great houses, that gets across some of the rules of Boston. The thing that is so sneaky about Spotlight is that its very plainspokenness is what makes it an exceedingly accurate movie about the city.

In the film, Rachel McAdams, playing reporter Sacha Pfeiffer, methodically knocks on triple-decker after triple-decker, impoverished, shabby homes, quietly asking questions about the church in a neighborhood where it was a locus of community, only to realize that very haven was the source of trauma and abuse. One of the film's most stunning moments comes when Pfieffer knocks on an ex-priest's door, and he talks about "fooling around" with young boys in a manner that's so straightforward, it's as if he didn't even realize that it was a transgression. “Sure. I fooled around. But I never felt gratified myself … I never got any pleasure from it. That’s important to understand.” Pfieffer keeps an even look on her face, but it's a scene in which you realize that this man of the cloth was probably abused, and he passed that abuse down. It's a history of pain. The Catholic church in Boston turned a blind eye towards its adherents, perpetuating decades of abuse—it's the kind of evil that emerges from power around which Spotlight raises complex, thorny questions about the roles that religion, politics, and influence have in shaping a city and its people.

Perhaps it's unfair to compare Spotlight to the Boston crime films that came before, the ones with origins in Dennis Lehane novels and Ben Affleck’s need to rebrand himself as an authentic filmmaker. But I've never seen a film that actually understands the way that, when I say I'm "Irish-Catholic" and from Boston, people may have certain expectations of me, true or not: an undying love of the Red Sox (when I wrote profiles for the Boston Globe that were centered around “a fun activity with a notable person,” the notable person would always suggest a Red Sox game; I always declined), a mild drinking problem, an ability to be loud and dirty, relatives named Meghan, and a tortured relationship with the role of the Catholic church in my life and my community. Boston crime movies always wave at the influence of the church, but it's schematic pulp practicality, a way of saying that a "bad man" may just be a man failing to be good. The thrill is in the plot. What Spotlight does, with admirable precision, is take the religious context of Boston apart, little by little, whether it's in the lives of the reporters who are digging into the case, with roots that go back to BC High (an all boys' Catholic school) or the lives of the victims upon whom the priests preyed.

Spotlight also gets at the community, how power and privilege can exist, cheek-by-jowl, with the demands of poverty. Religion can be a necessary salve for the lives of the poor, offering benediction and hope for people who need that promise—especially when the system they’re born into fails them right and left. That promise, in religion, can lead to unchecked power. In the case of the Catholic church, it left a legacy of trauma and abuse.

Spotlight traffics in nostalgia for a time when newspapers could afford to have investigative reporting, a time when there was institutional support behind speaking truth to power. I think it's a necessary nostalgia, both clear-eyed and a little sepia-toned, and it works fifteen years later, when the role of the fourth estate is increasingly compromised. Yet the thing that sticks with me is just how thoroughly Spotlight deconstructs some of Boston's mythology by outlining the truth of how power really worked in the city. It has little to do with criminals convinced they're the smartest ones in the room. At the end of the day, it's a matter of loyalty, and making choices that relate to something bigger than yourself, to the myths you buy into. Spotlight is a showdown between two sets of myths: truth versus the church, and it's a case where the truth wins out—at least in this round. And by prioritizing the truth, Spotlight makes the existence of "the Boston movie" feel superfluous, showing just the sort of hollow, empty, nonexistent myths Hollywood tries to sell to us at the multiplex.