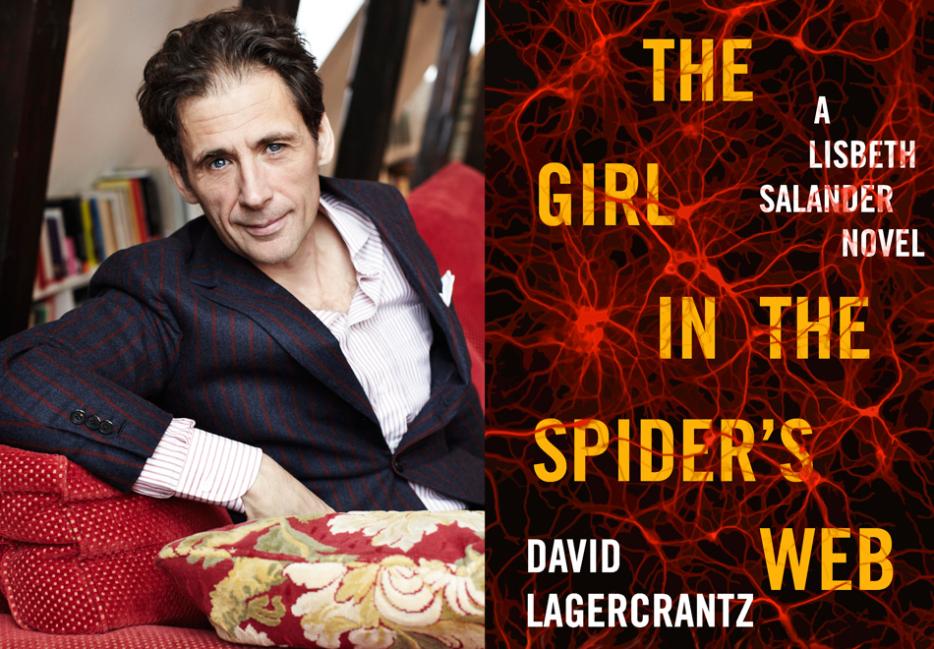

David Lagercrantz checked in late last night, but already Le Germain Hotel's lobby bookshelves are carefully curated to include his newest novel, Girl in the Spider Web (the latest in the Millennium crime series created by Stieg Larsson, who wrote the first three books before dying in 2004). It’s on every shelf—stacked charmingly atop guides to birds, tilted diagonally against expensive collections of modern photography, its spine clearly visible alongside unheard-of vintage titles (presumably chosen for their handsome book cloth more than anything else).

I’m here to interview Lagercrantz, and I’m psyched about it (almost as excited as whatever hotel honcho ordered one million of his books to display). But I’m also exhausted, because last night at bedtime I was psyched about it, too.

Now, zombie eyed, I listlessly run my fingertips across the hotel’s many objets-d’art. At one point, yawning, I find myself pressing the heel of my sneaker against the lowest rung of a ladder propped against the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves in the lavish lobby (to test its sturdiness! Is it for decoration or function?). Upon seeing me begin to climb, a hotelier approaches to be like, “Can I help you?” in a tone that suggests I may be looking for a couch to pee on.

“Don’t worry,” I say quietly. “I’m here for David Lagercrantz.” His eyes widen, like, Oh no, another stalker.

But then, to exonerate me, there he is, David Lagercrantz, springing up the steps to the lobby, arms outstretched like, I’m terrible!

“Sorry,” he says, “sorry.” He’s smiling and smiling, which I’ll soon learn is more of a handsome tic than an expression of happiness. Lagercrantz’s soft eyebrows begin just above his inner eye and drift downward until they touch his outer lashes. Sad little eyebrows, in other words. The disparity of expression, eyes versus teeth, could sum up what little I learn of him this morning. It’s charming, really, how he smiles regardless of how he feels, maybe because I relate—fear, worry, anger, regret, joy, triumph; Lagercrantz and I fold open our faces for any of it. Primates smile during moments of fear, too. Scientists call it the “Fear Grin.”

Now, David smiles at the hotelier, the hotelier smiles at me, I smile at the hotelier, at which point the hotelier literally bows, then slinks away with a sweeping gesture that indicates that Lagercrantz, and I by extension, can do whatever the hell we want. Emboldened, I immediately tear apart the white, worn-linen, down sofa to make myself more comfortable, tossing the backrest cushion onto the floor so that I have room to sit crosslegged with my back against the armrest.

“Good,” says Lagercrantz, smiling, nodding. “I like that. Getting comfortable.”

“Do you mind if I remove my sneakers?”

“Please. Would you mind if I eat my yogurt?” I see that a tray has miraculously appeared on the coffee table. But just for him. There is yogurt and one cup of coffee. “I am very hungry.”

“Not at all.”

He picks up the bowl, stirring in granola and strawberry paste. “Now where should I go? How shall we do this? There?” He points to my sofa kingdom. “Here? Sitting close?”

I pat the cushion next to me. And so we situate ourselves. I tell him that I love his outfit: green argyle socks, burgundy wingtip shoes, royal blue silk blend trousers, matching suit jacket with a navy pocket square dotted with magenta and pink flowers, detailed down to the green leaves, and a sky blue button down. He tells me I look lovely. I laugh riotously, and now we are friends, launching into a conversation that will cover everything from writing (duh) to movies, depression, Nazis, daughters, mental illness, and the beautiful, motivational force that is chronic terror.

*

David Lagercrantz: Is something the matter with your back?

Kathleen Hale: What? Oh. Kind of. I’m just trying to crack it.

DL: It’s the same with me.

KH: Probably all the travel, sitting on planes, typing.

DL: We got in late last night. I woke at four. I feel a little insane.

KH: Jet lag makes you crazy. How’re you liking Canada?—Oh wait, you just arrived.

DL: My daughters already have maple leaf sweatshirts.

KH: Assimilation! So I know your guy said we only have about … Geez Louise, 17 minutes. I’ll cram it in.

DL: I’m so sorry.

KH: No! You’re incredibly busy. But I was reading the Guardian interview, which said you mirrored Larsson’s habit of writing through the night.

DL: Wrongly put. I wake up very early, I was under such pressure [writing Girl in the Spider’s Web]. And my head was sort of burning. I woke up at four in the morning, sometimes three. That was morning for me, but maybe [it counted as] night for the reporter I talked to.

KH: What was an average day like for you, while writing the book?

DL: An average day … up at four … three thripple espressos.11“Thripple” is the actual word here, it means “triple” in case, like me, you were wondering. My wife gets up at six or something, we wake the kids at seven, I take them to school at 8, walk them to school, they go to the school now, 7 and 10, though I’ve also got a 21-year-old in London. Then I go home and write for a while, I do my best writing not writing, so I get my best writing done thinking while I’m walking home. So I write, pick up the kids, talk over my writing with my wife over a glass of wine, then I collapse.

Now, today I woke up at 4 or 5, because I’m jetlagged, my head burns.

"Lisbeth Salander is that combination you describe, of sufferer and rescuer. 'Knight in shining armor.' But for herself."

KH: Can we talk a little bit about this book relative to the others—for starters, you've described yourself as an actor-writer.

DL: Well. [Rolls his eyes with embarrassment]

KH: No, I just mean that you’ve talked about how your sister is an actor, and obviously a lot of writing this fourth instalment involved reading the first three books, which involved putting yourself in Larsson’s place. I just wonder if you ever felt as if you were method acting?

DL: [Waving his hand to indicate a language barrier] Remind me what is “method acting”?

KH: Oh, sorry. Well like, have you seen the Batman movies?

DL: Of course.

KH: And Heath Ledger?

DL: Quite sad.

KH: People say he died because he got too into the character. You know the Joker?

DL: Hm.

KH: The clown character. Ledger decided the character was schizophrenic, so he explored schizophrenia by attempting to live it—that’s the rumor. Drugs, locked rooms, conditions that would allow him to feel and understand what he was portraying.

DL: Ah! Yes! Now I understand. So you are asking if I felt at times there was method acting to channel Larsson, and maintain the consistency, and the answer is: “somewhat.”

It’s very easy to have a male hero that’s like yourself, but that was not a good thing for me, and I think I learned that a lot when I wrote [I am Zlatan Ibrahimović, 2011].

I grew up in this academic family where you were supposed to be sensitive, but not weak. And when I got into the world of [Ibrahimović, a footballer], something happened. I had to be tougher. I had to write in a voice that colluded with his experience. What got this whole circus going is that I love getting assignments.

It’s like how actors can be sort of boring, being themselves—you expect them to be their characters, but the reason they perform those characters is to feel something more exciting than who they think they are. Then they go into another role and then they shine. So I’m better when I collude with my material.

KH: And in what ways did you collude with Larsson?

DL: Continuance [of plot], but also principles. Racist is maybe not the right word to describe what is happening in Sweden. But [Larsson] understood, you see that in his public writing, he saw what was coming.

More and more, I’m afraid, we are like America. We have this tolerant beautiful side of Sweden … and then we have intolerance, growing intolerance, and a growing intolerance against the elite and against immigrants.

I could not have written [Girl in the Spider’s Web] if I had not shared his values. It’s about the moral pathos that you can feel between lines and that was important to me. I’m not sure if I succeeded or not. But I do think that when we are more tolerant of new people we will also become more tolerant of more ideas.

KH: In an interview with The Globe and Mail, you mentioned that one of the challenges in keeping the tone of this book consistent with the others involved keeping a commercial mindset. You said, “I tried not to be too literary.”

How do you define “literary fiction”?

DL: Well, [Larsson] was not a literary author, but I don’t say that in a bad way; he wrote effective journalistic prose. Quick, small. So I concentrated my writing to be more reporter-like.

Right now I’m working on a piece about [Alan] Turing—you know, the code breaker—and I’m trying to do the same. Less literary there, too.

KH: But… “Literary” …

DL: You know what I mean: more exact, with a small detail, and you develop thoughts a bit longer. You can have some cliché if it’s a thriller, but in a literary novel you can only use a cliché if you’re playing with it.

[With Girl in the Spider’s Web] I wrote my best, but there was a lot of metaphor and stuff I put off.

"Horror and crime can be great spotlights."

KH: [The series' protagonist] Lisbeth [Salander] is captivating all on her own. But I wonder whether the revenge fantasies she plays out appealed to you at all because you have daughters?

DL: You mean if anything happened to them?

KH: Well, yes, just in terms of like—well, she’s continually a victim, but she also reacts as her own savior. The violence she inflicts is similar to what, in any other story, might be unleashed by, say, her father—a man who loves her.

DL: Usually it is someone else doing the protecting.

KH: Exactly, and that’s a romantic violence. But this is more graphic, perhaps because it subverts the trope of male savior?

DL: As a writer, you use everything you can, and yes, in a way maybe Lisbeth interests me because she’s the opposite of the vulnerabilities I see in my kids. The society tried to refuse her but she refused to crush. She is that combination you describe, of sufferer and rescuer. “Knight in shining armor.” But for herself.

KH: Which is an interesting romantic allusion, since when your agent came to you with the idea of continuing this series, you were in the middle of writing a love story.

DL: Maybe I’m a bit sentimental. I have this romantic side.

KH: People seem to think it makes sense that you took on the project because you used to be a crime reporter.

Yet this book is so much less violent than the others. Do you think maybe working as a crime reporter, what you saw, did it make you squeamish about violence?

DL: [Nods, makes a face] People assume I was a crime reporter because crime was my fascination, a passion of mine. But in reality, I got a job. My father was very successful, and I had to break away from the family, find my own way, doing something different and simple.

KH: You mean like … less high class? An adventure in slumming it?

DL: [Smiles even bigger] It was a job. I lived in a small apartment, and I worked. It was what I wanted.

KH: So if fascination with violence didn’t engender your interest in Larsson’s work, what did?

DL: Horror. Horror and crime can be great spotlights. I’m eating this yogurt now and it’s quite boring, but if you know I’m going to get killed afterward the details become important. It is in those cases that I think violence works. Silence of the Lambs is a great example.

Body parts everywhere? I can’t do it. I don’t have it in me. And also I believe that you get more scared when you feel it between the lines. I sense it when I see movies with my kids. The darkness scares them more.

KH: But movies are different. You have a soundtrack that sets a tone. You have lighting. How do you create that tension with writing?

DL: With implication.

KH: Give me a specific example.

DL: [In Girl in the Spider’s Web] I had this choice where the sister is seducing Andre, and she says, “Now Andre, now I’m going to rip you with a knife,” and I think that’s enough, then you know. Or when you see the bruise on Hannah’s neck, you understand she’s having a hard time.

KH: It’s off page.

DL: Precisely.

KH: What did you mean in The Guardian when you said you were addicted to insecurity? Unless they got that wrong, as well.

DL: [Laughs] No, that was spot-on. I hate insecurity, I’m longing for my normal life taking the kids to school again, having my regular time, not facing the daily slew of negative reviews.

I think I have survived this thing. But it was a huge risk. For a while in Sweden I thought I wouldn’t survive it. The night it was released, I went to the bookstore and all the critics were scooping it up. They read it in two hours and by morning the reviews were up, scathing. They were hungry for blood.

I try to be nice—

KH: For what its worth, you’re delightful.

DL: Thank you so much, but maybe there’s something in me, my background …

[He plucks the lapel of his gorgeous silk suit jacket]

… my suit, something in all of it that provokes people. There’s a lot of hate.

KH: You mean, like, they’re put off by the fact that you’re rich.

DL: My family …

KH: Yeah, I’ve read that you come from an affluent family, but not being from Sweden I don’t know if that means you’re like, the equivalent of a Trump or a Kennedy.

DL: Pardon?

KH: Never mind, sorry—I’m sitting here like, “I know nothing about Sweden, but you must know everything about my dumb place.”

Anyway, the point is that it sounds like a class thing, a lot of this backlash, which I didn’t know before. And it’s probably confusing and frustrating for you, so I’m sorry because you seem very nice and sensitive.

DL: I am much too sensitive.

KH: I also think you’re very talented. But am I introducing new terms if I ask whether you feel like people dismiss you off the bat as untalented because you’re wealthy?

DL: In the ’70s when I grew up, we [Swedes] were so conscious about classes, and I can’t do anything about it, that Larsson and I were in different backgrounds. That is part of the Swedish society. There is now intolerance of immigrants, but intolerance of the elite goes back to the ’70s.

One thing: I got a call from my leading publicist recently, and excuse me to death for bragging, but we have something strange in Sweden—we have this critical list in the culture pages. People think that there’s too much “best seller” everywhere, so they made a high-brow list, poetry and other very difficult reading; they put my book in. Readers don’t care at all but given the critical backlash where I live, it felt very good.

It’s sometimes hard to feel good, though—there was something about that response in that I guess I didn’t expect it. Certainly those closest to Larsson. That’s really the sad thing is the estate thing and the widow. But I was shocked that the class issue was so important in a wider sense because I haven’t talked about that in a while and many people put that against me. It was very personal. There were many stupid questions, trying to pit me against Larsson.

KH: Like what?

DL: In Germany, a reporter asked me, “Weren’t you shocked when Larsson attacked the Wenger family?”

As if I should be shocked that he attacked Nazis.

KH: In terms of the negative reviews—among the countless positive ones, obviously, because your book is on every bestseller list—does your publicist send them to you, or do you seek them out? The negative reviews, I mean?

DL: I try not to, because it doesn’t make you good, and you shouldn’t.

This social media thing is danger for your brain, and sometimes I can’t resist it, but it’s too much now, thank God, I can’t keep up with it.

I survived it, I think, instead of being the victim. I’m a weak depressive guy, I am, but I took to it. I come from a family from a lot of success and mental illness. Sometimes it is destructive and sometimes, you know, I get depressed.

KH: Me too.

[He touches my hand. I pat his.]

DL: Being terrified is hard but it gets you going. It’s hard to be intolerant and hard against people when you know they’re capable of feeling—well, what you just said is an example—so I think you can use a lot from it as a writer, because often it takes a sort of illness to do it that makes you sensitive to people. When you’re in a manic state you trust your associations—“This would be brilliant, write it down!”—and then you go into depression you start to doubt yourself and that’s important too.

KH: When you’re depressed, you edit. Mania is for getting it all down, and the depression is for going through and cutting out the shit.

DL: Exactly! And when you’re in your deepest depression you don’t do anything at all.

KH: How often does that happen to you? The debilitation?

DL: [His chronic smile fades] I think my concentration is getting worse, and I think everyone these days, the phones and the updates with the bleeping and blurping. It’s a distraction.

Now [that I’m on a national book tour] I have spent the longest time not writing. I wrote a bit in early August. I brought my computer on tour thinking I’d have time then, too, which was stupid. Writing is my therapy. Not being able to do it, of course that makes me a bit depressed.