Four years ago, I experienced a moment that froze time. I was hiking in the White Mountains of New Hampshire when a fog descended. In the trees, it didn’t seem so bad. I could still make out a few bright orange markers, and the trail was wide and clear, easy enough to follow. I was headed down the mountain, back on the same trail I had taken earlier that day to the summit. I knew my way—or I thought I did. Far ahead of me, my then-boyfriend, Garrett, walked swiftly and purposefully over roots and stone, more sure-footed than I, and in better shape, too. Suddenly, the trees parted and I stepped onto an open expanse of bare granite. I could see no farther than a few feet in front of my face. Garrett was gone, and in his place, a white nothingness. At first, I was struck by the mercurial beauty of the cold, silencing fog. It enveloped me completely, a damp silver-white embrace. But soon, I realized my predicament. Somewhere to my right was a sharp cliff. Somewhere to my left was a slow, sloping embankment. In between was a path, marked only by a few scattered flat patches of faded spray-paint. I took a few tentative steps, my body moving molasses-slow through the vapor. I called for my boyfriend, but I heard no response. He had vanished. I was alone.

I have a lifelong fear of heights, but never had I faced a fall so blindly. I knew that should I veer the wrong way by a few feet, I would fall. I would hit rock, and then trees, and perhaps if I was lucky, a pine would slow my descent, but, if I were to fall, my soft body would certainly hit against the hard bones of nature. I could imagine exactly how I would break, how my skin would split and my organs would compress. Afraid and disoriented and haunted by these imaginary pains, I got down on my hands and feet and began to crawl, like a child, like an animal, until I again reached the relative safety of the forested path. I called for Garrett again and again, until, finally, I gave up and waited, crying against a pine tree, sticky, cold and exhausted, for him to return. For my sight to return. For the world to remember me.

This isn’t the first time I’ve gone astray in the mountains, and yet even though nature keeps reminding me of its raw indifference and hard edges, I keep coming back for more. I have moved several times in the past decade. Finally, I moved into the woods, where I live in a cabin surrounded by tall white pines and sugar maples. I can be hiking in the White Mountains in under an hour, and from my favorite lake, I can see their blue and purple peaks rising on the western horizon, a permanent streak of twilight.

Each move has brought me farther north, and closer to mountains.

Sometimes, it’s not enough to live nearby. At various times in my life, I’ve gone on pilgrimages to frosty mountains, Icelandic peaks and Canadian forests. I don’t vacation on beaches—I spend my money flying north, driving north, getting ever higher on the thin, cold air. One arctic winter, I was shivering in my parka, wrapped tightly in layers of scarves, my face surrounded by a halo of coyote fur. The deck was slick with layers of ice, and the snow came down wet and hard. It was past midnight and there was no one else on the deck of the ship, but soon they would come, ready to disembark. I wasn’t getting off at Lofoten. I would ride Hurtigurten ferry (which also doubled as a cruise ship for elderly Europeans and a mail boat for residents of the arctic islands) up to Hammerfest, a city located at 68 degrees north. But I chose this slow means of travel for one reason: I wanted to see Lofoten. I had planned my journey north around this archipelago, even though I could have flown from Oslo to Hammerfest in a matter of hours. I spent a week making my way up the coast, from ferry to train to bus back to ferry again. I ate nothing but bread and cheese; I slept in the tiniest budget cabin available. But I was determined to see these mountains.

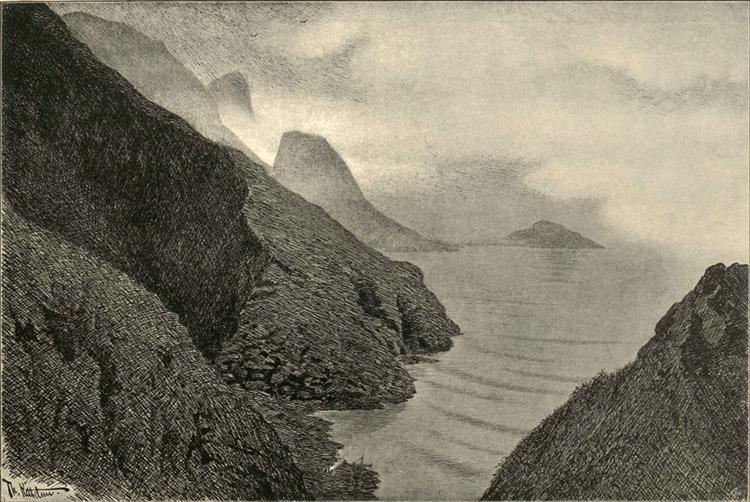

And I did see them, though it was dark and the world around me was washed in shades of indigo and gray, deep purples interrupted by a chain of yellow lights shining out of house windows and from street lamps. I could still see the mountains, which jutted from the ocean like broken teeth, ragged and sharp. In pictures, this landscape looked like something from a fantasy novel or a Magic: the Gathering playing card. In person, it was even colder, even more raw and sharp and brutal. It was beautiful; it was sublime.

Fra Lofoten, by Theodor Severin Kittelsen. Photo via Wikiart.

We tend to think about beauty as though it were an immutable quality. Evolutionary psychologists have spent years trying to convince the general public that we are drawn to certain traits for good reason. Some of this is utter nonsense—particularly when it comes to standards of feminine beauty—but some of it sounds plausible. We like symmetry because asymmetry can be a sign of illness or disease. We like flowers because they can help us figure out what part of a plant will be edible. Supposedly, we like glittery gemstones because the gleam of their crystalline structure reminds us of how light scatters on water. Water is needed for life to exist, ergo we find crystals beautiful because they remind us of quenching our thirst, of survival.

And yet, beauty doesn’t always work that way. We want beauty to follow logic, partially because we find comfort in patterns, in organization, in replication. We want to think an appreciation for certain scenery or certain items is innate, built into our brains and bodies from birth. But history tells a different story. Ugly and beautiful are two categories that mutate and overlap. The Lofoten Islands are now considered beautiful, a natural wonder, a place to go and take pretty pictures of rosy dawns and rustic fishing shacks. Yet once, they were ugly. Once, all mountains were ugly.

***

Edgar Allan Poe never visited Lofoten, but he chose it as the setting for his 1841 story “A Descent Into the Maelstrom.” In this short tale, the narrator climbs into the cliffs of Lofoten, led by a white-haired fisherman, where he is regaled with tales of the Moskoe-ström (the Viking version of Charybdis). “A panorama more deplorably desolate no human imagination can conceive,” writes Poe. “To the right and left, as far as the eye could reach, there lay outstretched, like ramparts of the world, lines of horridly black and beetling cliff.” The deadly whirlpool swirls and churns below the two men as they talk, discussing the deadly nature of this wildly gyrating abyss, the waves of which echo the mountains in their stark, sinister gray violence. In the distance, he spies still more islands, “hideously craggy and barren.” The land is “gloomy” and “ghastly” and the ocean is a frigid hellscape. The entire scene, cursed.

Poe’s description of these peaks is about as fantastical and morbid as one would expect from that death-dwelling writer. But horror has always served as a mirror for society and its discontents. Poe’s writing was extreme and exaggerated, but it wasn’t entirely out of step with how early Americans settlers generally viewed mountains, nor how their European predecessors understood the heights of the globe. Stephen Bayley, author of Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything, argues that although we’re now practically “required by custom” to admire Alpine vistas, “mountains were once thought disgusting: they were dangerous, frightening and home to nasty demons and bandits.”

Examples of this tradition can be found all over Europe, reflected even in the place names of various mountains and heights. In Northern Germany, high in the Harz Mountains, there is plateau called the Hexentanzplatz (or the “Witches’ Dance Floor”). Surrounded by strange rock formations, it was believed that this was where pagans came to worship. (In the same mountains, there is also a place called the Teufelsmauer or “Devil’s Wall”.) From the 1500s to the 1700s, it was common belief in Sweden that witches roamed the mountains, and that they flew to the highest peaks to have their check-ins with the devil. The 1600s saw a spate of witch trials and executions, the largest of which happened in the mountainous region of Gästrikland in 1675. The townsfolk of Torsåker were gripped by hysteria, driven mad by fear and religious fervor. Nearly one hundred people were accused, and seventy-one were put to death in a spot known as “The Mountain of the Snake.” The so-called witches were beheaded, drained of blood, and burned. These days, the town is perhaps best known for its annual bluegrass festival. “In the afternoons, the mountains get a bluish hue—its own Blue Ridge Mountain,” claims the festival organizers.

The Swiss, too, believed that evil dwelled in the heights. In the early 18th century, Swiss physician and philosopher Johann Jakob Scheuchzer published a natural history of the Alps, in which he described in great detail the hideous dragons that populated the mountains. Near the alpine town of Glarus lived an animal “with the head of a cat, with large eyes.” It was “long a foot, with a thick body, four limbs, and something like breasts pending from the belly… it was soft and full of poisoned blood.” Other eyewitnesses claimed to Scheuchzer that they had seen snake-like creatures with human faces slithering amongst the rocks. One man even said he saw a flying serpent breathing fire. The prints that accompanied Scheuchzer’s treatise are incredible, filled with sinewy, furry monsters with cats’ heads or baby faces. Their mountainous playground is shown in vivid detail. It’s a landscape of steep peaks and sharp edges, small figures lost in a world of heavy diagonals and dark shadows.

These images are interesting, but they are not beautiful. They emphasize the deadliness of the mountains and the hideousness of its creatures. Before the technological taming of the world, mountains and forests were places where bad things happened—trolls lurked, wolves prowled, and witches tended to their strange gardens and chicken-legged houses. Fairytales and folktales were filled with warnings, particularly for young girls. Don’t go out at night, don’t venture into the wilderness alone, don’t get raped, don’t get captured, don’t let yourself be ruined. In fairytales, fear and ugliness have always been deeply intertwined. Villains have scars on their faces and witches have warts. The landscape followed the same sort of circular logic. If it was bad, it was ugly, and if it was ugly, well, then it was probably bad.

This only began to change in the 18th century, and even then, mountains were appreciated for the emotions that they could induce: the awareness of human smallness and frailty, the sense of wonder and fear, the reminder of mortality. Some artists were able to see the beauty of the mountains from an earlier date, argues Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. “This is one area of the imagination where artists seem to have been ahead of the curve,” he writes, citing Leonardo da Vinci and Titian as examples. These Renaissance artists (both of whom hailed from mountain towns) painted glorious scenes of the high life, but, adds Johnson, “a lot of the time, in Renaissance art, a mountain is just a sharp jagged dry rock.” Mountains were “ugly raw wildernesses of stone, murderous enemies of cultivated life.”

Perhaps the largest factor in the widespread rewriting of the peaks came from Natural theology. This doctrine, which spread across Europe in the early 1700s, argued that “the world in all its aspects was an image given by God to man,” writes Robert MacFarlane in Mountains of the Mind. “To scrutinize nature, to discern its patterns and its idiosyncrasies, was thus a form of worship… Therefore, to visit the upper world and contemplate its marvels was to be elevated spiritually as well as physically.” MacFarlane argues that the advent of Natural theology was “crucial in revoking the reputation of mountains as aesthetically displeasing.” If such majestic and towering creations were the work of God, a majestic and towering force in His own right, then how dare we think of them as anything but beautiful?

While some early naturalists believed peaks harbored treacherous beasts and unnatural women, a few also considered them a more neutral source of magic. Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner lived during the 15th century and his writing showed him to be a “lover of the mountain world in a century when such love was considered lunatic,” writes MacFarlane. Gesner proposed that mountains were a place unlike any other, where the normal laws of physics need not apply. Even the brightest sunlight couldn’t melt ice, and normally transparent winds became startlingly visible. “Up there,” Gesner wrote, waterfalls could flow upwards.

Like Gesner, MacFarlane feels the presence of some “other-place” when he’s high in the mountains. I imagine this is what deep-water divers feel like when they’re descending into deep blue caverns, or what astronauts feel when they leave earth’s gravitational pull. “Going into the mountains—into what one nineteenth-century poet called ‘that weird white realm’—is like pushing through the fur coats into Narnia,” writes MacFarlane. “In the mountainous world things behave in odd and unexpected ways. Time, too, bends and alters… And if something goes wrong in the mountains, then time shivers and refigures in the moment, that incident.”

Between the 1700s to the 1900s, the cultural messaging around mountains underwent a series of transformations. Slowly but surely, mountains went from being viewed as “ugly and fearsome” to “terrible but godly” to “beautiful and vital” (to, finally, with the late 20th century embrace of ski culture, “fun and fancy”). Once modernity took hold, many previously negative (and previously dangerous) things began to seem less threatening. Fears changed, and aesthetics naturally followed. In Winter: Five Windows on the Season, Adam Gopnik classifies the “mind for winter” (named after a line in Wallace Stevens’ poem, “The Snow Man”) as a thoroughly “modern taste.” “A taste for winter, a love for winter vistas—a belief that they are as beautiful and seductive in their own way, and as essential to the human spirit and the human souls as any summer sense—is part of the modern condition,” Gopnik writes. Likewise, he identifies the cultural appreciation for the “mysterious, the strange, the sublime” as a modern taste. Although Gopnik is writing about a season, he could also be talking about the landscape itself. Having a mind for mountains is a modern construction, like being able to enjoy abstract art or ride through the landscape at 70 miles per hour without fainting from dizziness. Just as the word “awesome” changed meanings over the centuries, shifting from fearsome and terrible to radical and excellent, so too have the mountains moved. Our inner landscapes have shifted to accommodate new forms of beauty, old forms of worship.

***

I’m drawn to the jagged heights, pulled as though my heart was a magnet and they were aching heaps of lodestone. Like other residents of Maine, I call the long purple sprawl of Katahdin “beautiful” and extol the aesthetic virtues of Tumbledown. And I suppose they are lovely, particularly Tumbledown Mountain. With a clear blue glacial pool at the summit, ringed by evergreens, it makes for pretty pictures. My local mountains are just as good—Mount Douglas looks down upon a landscape of evergreens and lakes that shine silver in the cloudy light and Mount Pleasant is strewn with boulders and covered in lichen, sage green and granite gray.

But I don’t really go into the mountains to take pictures, nor do I go on hikes to see natural beauty. I chase something else. I enjoy feeling displaced, untethered, unstrung from the ties of my life. I go into the mountains for the same reason people once believed they were ugly, for the same reason I watch horror movies and for the same reason I enjoy standing on the frozen beach in the middle of winter. It’s the frisson of excitement, the sense that is just one wrong step away. I’m drawn to the feeling of vertigo. I like wondering whether I will jump.

There is a tinge of magic in danger, and there is beauty to be found in the sublime. Instagram may be the greatest enemy of real life wonderment, but still, I use it to document these moments. I take pictures, small flat squares to hold the memory of these grand encounters. On every hike, I find myself stocking my pockets with round pebbles and Lilliputian pinecones. The same impulse leads me to fill my digital storage with miniature versions of nature. These are fragmentary souvenirs, shards of the thing, but I keep collecting them anyway, hoping that a photo will stand in for the palliative pain of seeing my smallness, feeling my insignificance.

I didn’t always upload the image to Instagram, and I certainly don’t paint them or print them out. I mostly keep the beauty to myself. But I still might, on a day when I feel too small. But for now, these frail images serve as a visual synechdoches, like the pebbles I collect, like my beach stones. It’s something I use to mark my movement through the world. A trail of breadcrumbs leading from my mundane, boring digital life to the weird, fantastical beauty beyond.