Kisses #1– 3

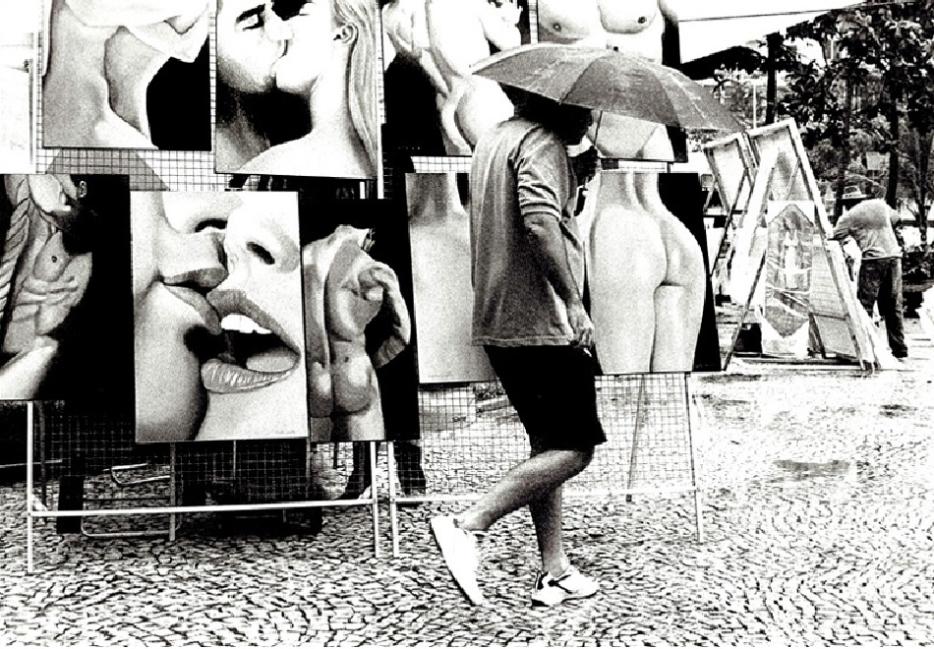

I kiss you for the first time, and it starts to rain. You tell me it’s a sign of something, maybe good luck. We don’t have an umbrella, so we just stand there kissing, getting wet, and I think about what you said. The idea that the sky is talking to us makes me uncomfortable, but I don’t say that, and hug you instead. You mistake my hug for agreement, and let your face sink into my shoulder. The air smells clean.

The second time I kiss you is an attempt to comfort; you’ve just found out your cat died. I don’t like cats, but that would clearly be the wrong thing to say, so I think maybe a kiss could fill in for words. Your sadness makes your lips soft, too soft, and I feel like I’m shaping a kiss out of Play-Doh. You know the difference between passion and empathy, of course; you stop me, your left hand between our mouths. I walk away from you; this is noon and New York and the street is roaring. You are alone now with your distance, with your sorrow, with the memory of your dead cat.

I kiss you a third time, two weeks later, and it’s a good kiss—just the right balance of wetness and dryness, closeness and a sense of self. You are the reason this kiss is a success, this is your accomplishment. I am impressed, and decide to document every lip encounter between us from now until there is nothing more to document. This will be three years later, in an ice- cream parlor on Sixth Avenue, where you will kiss me with chocolate- chip cookie dough and finality, and I will let my ice cream drip all over my new tank top after you’ve gone, like in a bad movie.

For now, documenting helps me forget what I don’t yet know.

Kiss #17

I kiss you in a swimming pool. The lightness of my body in the water makes me feel inconsequential. I try to leave my frustration out of our kiss, but that’s the thing about kisses, isn’t it? You can never leave anything out.

The smell of chlorine stays in my skin for two days. I take multiple showers, because I don’t know how to passively wait for things to get better. You say that I’m crazy, that I’m imagining things, imagining the chlorine. I pretend the smell is gone before it really is.

Kiss #99

This is a Sunday- morning kiss in upstate New York. We are at a bed- and- breakfast. It has been a long time since you kissed me like this, and it reminds me of that kiss that made me fall in love with you (see kiss #3). Yesterday was filled with disappointment; we got lost and couldn’t find I-87, then the hot tub wasn’t as big as you’d expected. But this kiss, the first thing that happens to me on Sunday, is light with possibility and future.

Kiss #146

This is the kiss that tells me the rules have changed. I clearly taste salami, which I know you don’t eat, and your tongue is doing something it’s never done before: some kind of loop to the left, then to the right; it feels calculated and foreign, and my mouth goes numb.

Kiss #147

I kiss you again, two hours later— an attempt to replace the memory. You would never let me kiss you if you knew my motivation, because you think I’m always treating life as if it’s a film and pretending to be the director. I want this kiss (#147) to prove the former (#146) wrong. It does not. I decide to ignore it, ignore the salami.

Kiss #163

The promise kiss. There’s something I need to tell you, you say, and Salami has a name now, though I refuse to repeat it. You promise me that it’s all behind us. You say it was just a slip, and I keep thinking, Slip, slip, slip of the lip.

Kiss #212

This kiss tells me you’re bored again. We are at MoMA (this is before they closed, before they renovated, before they reopened; by then we will not be together). We look at a beautiful black woman Chris Ofili made from elephant dung. The couple next to us finds it romantic. They laugh, and mid-laughter the man grabs the woman by her shoulders. It’s a powerful gesture; his hands are telling her he is sure.

We look at them, and it seems that we’re supposed to follow. But in our kiss there is nothing but habit. I realize then that we are not really done with Salami— that when you let things like that in, they can never find the way out.

Kiss #288

Kiss #288 gives me false hope, which, without the perspective of time, appears simply as hope.

We are visiting your parents in California, and it is going well. I’ve already met your dad when he was in New York on business, but everyone knows it is the mother who decides how the parents feel. She will announce her verdict with her arms, I know, when she hugs you goodbye before we leave. But this will only happen in two days, and now, on the evening of our arrival, everyone is tired except us, though we are the ones who should be sleepy, with our internal clocks still on East Coast time. You sneak into the bathroom when I go there to pee, and we kiss with the excitement of teenage rebels.

Kisses #289– 301

These kisses are an attempt to relive that bathroom kiss, kiss #288. We look for dark places, inappropriate places, places lived in by people we don’t even know. When there are no more excuses for hiding, we hide in private and pretend it’s the same. When we can no longer pretend, we lie. Hiding was something we found exciting for a while, we say, and now we’re over it. When the lie is exposed, we look the other way. I know what you are thinking: we’re like the worst poker players on earth, refusing to look at the cards we are holding.

When winter comes, I know the end is close. When I tremble at night because the window is cracked, you hold me, and you let your hands run up and down my back, my arms; but there are no more kisses. All winter long I wait for you to show up with empty boxes, a duffel bag, something that can host your belongings as they depart from shelves and drawers. I say nothing about it, and clean the apartment twice every day because I don’t know how to passively wait for things to get worse. When I cry one evening for no reason, you kiss my tears, and I wonder whether or not it counts, whether or not it should be documented. By the end of winter I know, the way events sometimes unfold in a woman’s mind before their time, that our first ice cream this summer will be our last.