Translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft.

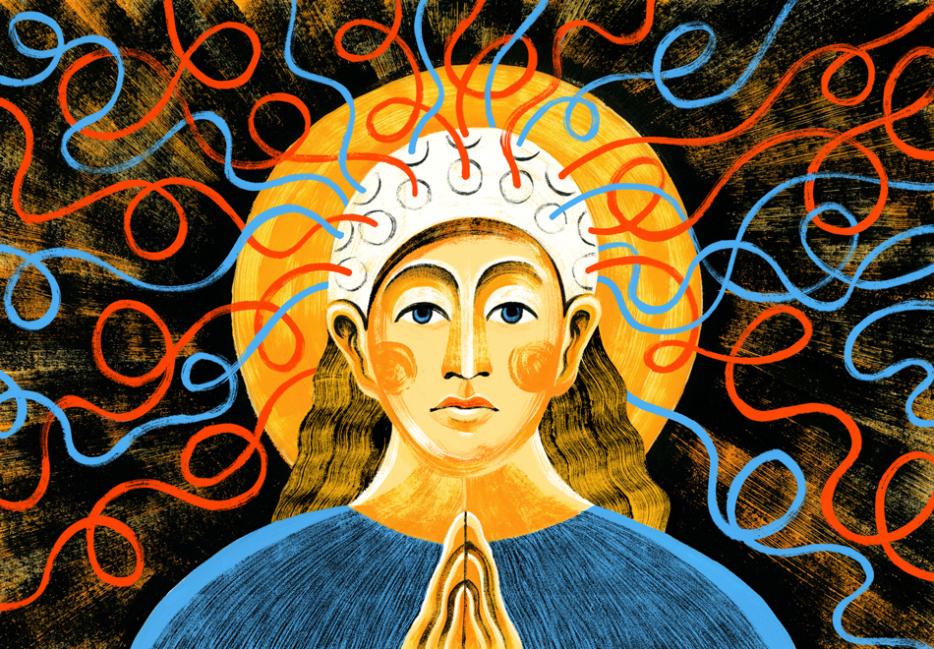

The plane arrived over Zurich when it was supposed to, but for a long time it was obliged to circle the city, since snow had covered the airport, and we had to wait until the slow yet effective machines had managed to clear that snow. Just as it landed, the snow clouds parted, and against the orange blazing sky there were contrails in tangles that transformed the firmament into a gigantic grid—almost as though God were extending an invitation to play a round of tic-tac-toe.

The driver who was supposed to pick me up and who was waiting with my last name written out on the lid of a cardboard shoebox was quick to state facts:

“I’m supposed to take you to the pension—the road up to the Institute is completely snowed under. We won’t make it to there.”

But his dialect was so strange I could barely understand him. I also felt like I had missed something. It was May, after all, the eighth of May.

“The world’s turned on its head. Just take a look at that.” He placed my luggage in the car and then pointed to the darkening sky. “I’ve heard they’re poisoning us with it, airplane fumes altering our subconscious.”

I nodded. The grated horizon really did trigger unease.

We reached our destination late at night, traffic jams everywhere, cars’ wheels spinning in place, all of us moving at a snail’s pace—at best—in the wet snow. Gray slush arose along the roadsides. In town the snowplows were in full force, but farther along, in the mountains, which we began to climb, very carefully, it turned out there was no one clearing the roads. My driver clung to the steering wheel, leaning in; his ample aquiline nose pointed out our direction like the bow of a ship pulling us through a murky sea towards some port.

The reason I was here was that I’d signed a contract to come. I was supposed to administer a test to a group of teenagers. It was a test I had come up with myself, and for more than thirty years, it had remained the only one of its kind, enjoying considerable renown among my fellow developmental psychologists.

The honorarium they had offered me was very large. When I saw it in the agreement, I was sure they had made a mistake. I was also bound, however, by the strictest secrecy. The company that was conducting the analysis had its headquarters in Zurich, but I hadn’t recognized its name. I can’t say it was only the money that convinced me. There were other reasons, too.

I got a shock when I found out that the “pension” my driver had mentioned was in fact a few guest rooms in a dark ancient convent at the mountain’s base. An outpouring of dense light from the soda lanterns just outside it displayed chestnuts suffering on account of the snow, already flowering; now, white and muffled under little frozen pillows, they looked like subjects of some incomprehensible, absurd oppression. The driver led me to a side entrance and carried my suitcase upstairs. There was a key sticking out of the door to my room.

“All the official procedures have been dealt with. You just rest. I’ll come back for you tomorrow,” said the driver with the big nose. “You’ll find your breakfast in the fridge. And the sisters will have you down for coffee at ten.”

Not until I took my medication did I fall asleep—after I had found myself back inside my treasured time hole, into which I and my body were both happy to fall as though into a fully feather-lined nest. Since my illness had come, I had been training for this mode of non-existence every night.

*

At nine, I watched the strangest coffee ritual I had ever encountered. I was in an enormous space, in the center of which stood a massive wooden table that bore the traces of many centuries’ use, and around it sat six old women in religious habits. They glanced up at me when I entered the room. There were three of them on either side; their identical habits made their facial features also look alike. A seventh sister, bustling about, bursting with energy, wearing a striped apron over her nun’s clothes, had just set out on the table a sizeable coffee pot and, wiping her hands on her apron, she now came up to me, holding those bony hands out before her.

Welcoming me, she was a little on the loud side, though this, too—as I’d soon understand—had its explanation: most of these old ladies were fairly hard of hearing. She introduced me to the rest by my first name and rattled off the nuns’ names, which were odd. The eldest was called Beatrix. There was also Ingeborg, Tamar and Charlotte, as well as Izydora and Cezarina. Tamar’s stillness made you want to watch her. She looked like a statuette of a primeval goddess. She sat atop a wheelchair, her body round, her face pale and beautiful emerging from her body’s habit. I felt as though she were looking through me, as though she glimpsed—beyond me—some expanse. By now, I thought, she would have joined that valiant tribe that inwardly ranges over the alpine meadows of memory; to that tribe’s members, we are but pesky specks on the surface of the eye.

Taken aback by the whole, I made a closer inspection of the vast bright space, which was divided into dining room and kitchen, the latter containing powerful multi-burner gas stoves with ovens as well as a bread oven, while its walls were crowded with huge hanging pans and shelves stacked with pots. Sinks unfurled under the window, one after the other, like in the back of an industrial canteen. The counters were covered in sheet metal, and metal, too, were all the fixtures, not one of artificial materials, all linked by bulbous tubes as though straight off Captain Nemo’s ship. The sterile purity that predominated here also immediately brought to mind old-fashioned laboratories, Dr. Frankenstein and his frightening experiments. The only modern additions to the room took the form of the colored recycling bins in the corner.

Sister Charlotte explained the colossal kitchen had not in fact been used in years, and that now the sisters cooked for themselves on a small gas stove or ordered the catering services offered by one of the local restaurants. Sister Anna, the woman wearing the apron—the prioress, as it turned out—added that back in the sixties, when she had first arrived, the convent had held some sixty sisters from all over Europe.

“Once, bread was baked here. We would make cheeses, thirty-five pounds each. But there’s no sense now in making cheese or baking bread for seven of us…” Sister Charlotte said, sounding like she was just getting started on a much longer story.

But Sister Anna interjected: “Eight of us! For eight,” she cried brightly. “And please come and see us once you’re up there.” With her chin, she indicated a direction I could not yet know. “The Institute belongs to us, as well. There’s a shortcut through the pastures, which makes it a half-hour walk.” The coffee pot was being passed from hand to hand now, coffee streaming darkly into cups, releasing steam. Next the nuns’ hands seized upon the cream containers, elderly fingers meticulously peeling back the tinfoil of their covers, pouring the cream into their coffees. Then they were tearing the tinfoil clean off, and then it traveled to their tongues, like an aluminum host.

In a single lick, their tongues had restored that host’s unadulterated glisten, its cleanliness. After a while, those scrupulous tongues went into the containers, too, to rid them of whatever remained there, and they did eliminate even the tiniest droplets of cream. The sisters seemed pleased to lick the cream up, and they did so with the practiced expertise of people who had gone through those same motions hundreds of times. Now it fell to them to shell the plastic container, removing the paper band it had been swathed in. The sisters’ fingernails found out the glue with sensitivity, tearing off the bands in triumph. As a result of all these operations, every sister ended up behind a little pile of plastic, paper and aluminum, those three raw materials.

“We care very much about the environment. We humans are an exceptional species, but we risk extinction if things keep going as they are,” said Sister Anna, giving me a knowing wink.

One of the sisters giggled. “You’re right, sister, it’s one a year, like clockwork.”

Consumed by the repetition of their activities, I hadn’t noticed an eighth woman coming into the kitchen, seemingly silently, and sitting down next to me. It wasn’t until she made a very small movement that I turned to her and saw a very young girl wearing exactly the same habit as the older nuns. She had dark skin, its vivid tint standing out against the pale backdrop of the others, as though for this portrait inside this painting she had just been touched up with fresh paints.

“That’s our Swati,” announced the prioress with evident pride.

The girl smiled impersonally, stood and began to collect the recycling, already separated into the appropriate categories, and to deposit it inside the colored bins.

I was grateful to the prioress for receiving me as though I were an old friend. When her cell phone started ringing, she hurried to remove from her pockets all sorts of items: keys, pastilles, a little notebook, a sheet of pills… The phone turned out to be an old Nokia—an antediluvian artefact.

“Yes,” she said into the phone in that strange dialect. “Thank you.” And then, to me: “Your driver is here, my child.”

I let myself be led through the labyrinths of the old building to the exit, lamenting my undrunk coffee. Outside I was blinded by the May sun; just before I got into the car, I overheard for one moment that concert of everything melting, fat drops splashing down from all sides, drumming against the roof, the stairs, the windowpanes, the leaves of trees. A lively river already rushed beneath our feet, transforming the eccentricity of snow into the banality of water and carrying it down and away, into the lake. I don’t know why it struck me in that moment that all those old ladies in habits were prepared for death, awaiting it with dignity. And here I was flailing in its face.

*

“You’ll have excellent working conditions here, please have a look,” said Dani, the program’s director, when I arrived at the Institute that day. She spoke English with an Italian accent, although her face suggested Native American, maybe even East Asian, ancestry. “This is your office, so you won’t even need to go outside to get to work.” She smiled. Next to her stood a man in a plaid button-down shirt that strained over his paunch. “This is Victor, our program manager.”

She said that not far from here there was a trail for tourists, and that without too much effort—some three hours’ or so—you could reach the top of the monumental mountain, visible from everywhere, which tended to give one the impression one was still in the lowlands, even where we were. The Institute was a modern concrete building in which straight lines reigned supreme. Aluminum bands supported enormous panes, the glass reflecting the irregular shapes of the natural world, which lessened somewhat the severity of the block. Behind this there was another large edifice, that looked to have been built in the early part of the twentieth century. It was almost indistinguishable from a school, especially since I caught a glimpse of a field out in front of it where a group of teenagers was playing soccer.

I was overcome by fatigue, no doubt because of the altitude, although also perhaps just because lately I had felt fatigued more or less all the time. I asked to be taken to the room where I was to stay over the next few weeks. In my condition, taking an afternoon rest is always a good idea. My exhaustion tended to arrive around two, when I’d get sleepy and sluggish. I’d have the sense then that the day was breaking down, that it was getting depressed and that it might not be able to pull itself together by the evening. But it would drag itself towards seven, often not dropping until midnight.

I didn’t start a family, didn’t make a home, did not ever plant a tree. I dedicated all my time to work, to ceaseless research, submitting my results to the complex statistical procedures I always trusted more than my own instincts. My achievement in life was a psychological test that enables the researcher to detect psychological characteristics in statu nascendi, meaning those characteristics that have not yet fully crystalized, not yet taken hold in the system that is the mature personality of an adult. My Developmental Tendencies Test earned rapid recognition around the world and was almost universally implemented. Thanks to it I became well known, got tenure at my university and lived a peaceful life, always working to perfect the details of the procedure. Time showed that my DTT had very high predictive powers, and that by administering it, you could in most cases foresee what a given person would become, what direction his or her development would take.

I never thought I’d dedicate my life to just one thing, doing the same thing over and over again. I used to think I was a restless soul, often taken by fervent passing fancies. If I’d been able to take my own test as a child, I wonder whether it would have shown I would become industrious, the tireless rhapsode of a single idea, refiner of a single chased design.

*

That evening, the three of us went into town for dinner at a restaurant where great slates of glass overlooked the lake directly, ensuring guests a soothing view of that black water, sparkling with the lights of the town. This quivering abyss drew my gaze relentlessly, away from my companions as they spoke. We had pears with honey and gorgonzola, then truffle risotto—the most expensive dishes on offer. The white wine was also among the best on the menu. Victor spoke the most, and his low-pitched voice drowned out—thankfully—the music, mechanical and cold, coming insistently from somewhere. He complained that these days we lacked people with charisma, that in our age people were so ordinary that they didn’t have the strength to change the world for good. His plaid-clad belly polished the table’s edge. Dani spoke to me with polite respect, in a confiding tone I liked. She leaned over the table to me, the fringe of her scarf dipping dangerously close to her plate, threatening submersion in melted gorgonzola. Of course I asked them questions about the children we were to study. Who were they, and why were they to undergo the test? What was the purpose of “our program”? Though I also knew it wasn’t any of my business, really.

We did converse, but I was focused above all on the taste of the tiny slivers of truffle, no bigger than a match head. The children were brought here for a three-month period, which they would spend in a so-called alpine school. There, as they learned and played, their abilities would be monitored and studied. All were adopted, they said, and the purpose of the program was to analyze the flow of social capital into the development of the individual (he said) and/or the impact of the whole range of environmental variables on future professional success (she said). My task was simple: I was to conduct my test in its widest-ranging version. They wanted precise profiles and future projections. The research was for private enterprise. The sponsors had all the permits and permissions they could possibly acquire; the program had been going on for years but was still being kept under wraps, for now. I nodded, pretending I was listening and taking all this in, though the entire time all I was doing was relishing the truffles. I had the feeling that since I had been ill, my sense of taste had layered, or splintered, meaning that every element of food would be interpolated on its own: mushrooms, bites of wheat pasta, olive oil, parmesan, tender bits of garlic… I had the feeling, in other words, that there were no longer dishes, just loose confederations of ingredients.

“We’re so grateful that a megastar like you was willing to come here in person,” said Dani, and our glasses met in a toast.

We talked politely and at leisure, enjoying dinner, until the wine had loosened our tongues a little bit more. I told them how any hint of predicting the future inspires fascination in people, but also strong, irrational resistance. It also leads to a claustrophobic unease, which is likely the same fear of fate with which humanity has been struggling since the time of Oedipus. In our hearts of hearts, we never want to know the future.

I told them, too, that good psychometrics are like brilliantly constructed traps. Once the psyche has fallen into them, the more it flails, the more it struggles, the more it betrays about itself, the more evidence it leaves behind. Today we know that a person is born as a kind of ticking time bomb of different potentials, and that the process of growing up is not at all one of enrichment and learning—it is instead the elimination of one possibility after the next. In the end, out of a wild, lush plant, we become something more along the lines of a bonsai—stunted, cut down to size, just a stiff miniature of all our possible selves. My test differs from the others in that it shows not what we gain in maturation, but rather what we lose. Our gamut of possibilities gets slimmer and slimmer—but it is also this that makes it relatively easy to predict what we’ll become.

My whole academic career was inextricably connected with ridicule, deprecation, accusations of parapsychology and even of falsifying results. Without a doubt it’s because of this that I became such a suspicious person, quick to get defensive. First I would attack and provoke, and then, troubled by what I’d done, I would retreat. What angered me the most was the accusation of irrationality. Scientific discoveries often seem irrational in the beginning, because it’s rationality that delimits knowing; in order to cross the border into the unknown, we must frequently set aside rationality, throw ourselves into the darkest depths of the untested, precisely so that bit by bit we can make it into something rational—so that we can comprehend it. When I was still traveling the world giving talks about my test, I would start each one by saying, “Yes—although I know this will upset you—a person’s life can be predicted. The tools to do it exist.” Invariably these words would meet with a tense silence.

*

When we entered the common room, the children were playing some game that consisted of acting out scenes. Already from the hallway we had heard bursts of laughter. Then it was hard for them to acquire the seriousness they needed to greet me. I would have been around the same age as their grandmothers, which instantly generated between us something like a warm reserve. They weren’t attempting any liberties. One brave little girl, petite and very resolute, asked me several questions. Where was I from? What language did my mother speak? Was this my first time in Switzerland? How bad is the pollution in the place where I live? Do I have a cat or a dog? And what kind of test would it be? Would it be boring?

I’m Polish, I began, answering each question in order. My mom spoke Polish. I’ve been to Switzerland several times and have many friends at the university here in Berne. The pollution is significant, though still significantly less than in the place I moved from. Especially in the winter, when our northern hemisphere increases the production of smog many times over. In the country, where I live, you don’t have to wear masks over your face. The test will be quite pleasant. You’ll have to fill out a couple of quizzes on a computer about very ordinary matters—for example, what you like and what you don’t, and so on. You’ll also look over some strange three-dimensional blocks and tell me what they mean. Parts of the test will be conducted with the aid of an innovative new machine, which won’t hurt—at most it may tickle a little. You will certainly not be bored. For several nights you’ll sleep in a special cap that will monitor your sleep. Some of the questions may seem very personal, but we promise complete confidentiality. So I will always be asking for your utmost frankness. Some of the test will be tasks you’ll get to do, which will seem to you like games. I can assure you that our time together will be enjoyable. Yes, I did have a dog, but a few years ago he passed away, and since then I have not wished to have pets.

“Didn’t you want to clone him?” asked a clever little girl who, as it would turn out, was called Miri.

I didn’t know what to say. I had not considered it.

“They say they do it all the time in China,” said a tall boy with an elongated olive face.

The dog question engendered a brief, chaotic discussion, but then the introductory niceties were evidently seen to have been performed, and the children returned to their play. They let us join in—it was, I understood, a version of our game of Ambassador, in which the players must communicate some piece of information through body language alone, without a word. We played without splitting up into teams, all playing on behalf of ourselves alone. I wasn’t able to guess anything correctly. The children did snippets of games of some sort, films I didn’t know. They were from another planet, and they thought fast, in shortcuts that led to worlds that were, to me, altogether unknown.

I observed them with the pleasure with which one looks at something that is smooth, young, springy, nice, connected directly to life’s sources. The wonderful timidity of that which did not yet have established boundaries. Nothing in them had been destroyed yet, nor anything ossified, nor anything encysted—they were just organisms, gleefully striving, clambering up and up and up in the thrill of the awareness of a summit.

Now, when I reach back into the memory of that scene, I can see clearly that the ones who stayed in my mind were Thierry and Miri. Thierry, tall, darker-complexioned, with heavy eyelids, as though always bored, not even fully conscious. And Miri—petite, concentrated inwards like a spring. I did also examine the twins. When one enters a room where there is more than a single set of identical twins, one immediately has a strange sense of unreality. Here, too, I had it. The first set: boys sitting far away from one another—their names were Julian and Max, both stocky, with dark eyes and dark curly hair and big hands. Then, two tall blond girls, Amelia and Julia: identically attired, focused and polite, sitting close together—so close their shoulders touched. I watched them in fascination, involuntarily searching for details that might differentiate them from one another. Others, like Vito and Otto, did everything they could in order to lessen the resemblance: one with a buzz cut, the other with long hair, one dressed in a dark shirt and dark pants, the other in shorts and a rainbow-colored t-shirt. It took me a moment to realize they were twins, and then I caught myself staring at them in amazement. They smiled at me, probably accustomed by now to looks like the one I had given them. Next to Miri sat Hanna, a tall seventeen-year-old with the figure of a model and an androgynous charm. She barely took part in the game, smiling only slightly, as though her mind were somewhere else. Tall, slim Adrian—nervous, hyperactive, tending to take charge—would leap to guessing first, spoiling the others’ fun. And Eva, who in a somewhat maternal tone would quiet him, trying to restore some order to the room. They were the types of children that made up any summer camp.

*

The next day I started the first part of my inquiry, which was dedicated to psychoneurological parameters—a largely mechanical segment. Simple memory and perception tests. Blocks arranged in the appropriate order, reading strange drawings, one eye, the other eye. As I had promised, they had a good time. In the evening, as I put the data through my computer, Victor came to see me.

“I just wanted to remind you of the secrecy clause you signed,” he said. “Save files only to our internal storage systems. Don’t use any of your own.”

This irritated me. It struck me as disrespectful.

Later, when I was smoking my daily joint on the terrace, an uneasy Victor popped into my room once again.

“It’s legal, I have a prescription for it,” I clarified.

I handed him the joint, and he inhaled deeply, expertly. He kept the smoke in his mouth, narrowing his eyes as though preparing himself for a completely different sense of sharpness, a vision in which everything would be defined by wonderfully soft contours.

“Did you hire me just because I don’t have much longer to live? Was that the point? That’s the best guarantee of secrecy, right? The silence of the grave.”

He emitted a little bit of smoke, swallowed the rest. For a moment he stared at the floor like I had caught him in a lie he’d only just come up with. He changed the subject. He told me that predicting a person’s future on the basis of some test was an affront, in his opinion, to sound reason. But he was a loyal employee at the Institute, and he represented the test’s commissioner, and so he would not publicly express such reservations.

“What’s the test for?” I asked.

“Even if I knew, I couldn’t tell you. That’s not going to change. I suggest you make your peace with it. You just do your thing, and get some fresh Swiss air. It might do you good.”

I sensed this was his way of acknowledging he had known about my illness. Afterwards he said nothing, just focused on smoking.

“How do I get to the convent from here?” I asked him after a while.

Without a word, he took out a notepad and drew me a sketch of the shortcut.

*

It was true: the way down to the convent was an excellent shortcut, some twenty minutes walking quickly, zigzagging between pastures. You had to pass through a couple of cattle gates and, several times, squeeze in alongside the fences’ electrical cables. It took me a moment to say hello to the horses, who, stunned by the spring sun, stood motionless in the melting snow, as though contemplating that climatic contradiction and trying to find in their big slow brains some sort of synthesis.

Sister Anna let me in wearing a white apron—she and Swati had been cleaning. There were boxes of documents lying on the pews in the hallway. The sisters were dusting them off and then transferring them to a cart so that they could be taken downstairs. The prioress seemed eager to abandon this task and to take me on a ride in the brand new elevator. We went up and down several times, covering a distance of one floor between the residential part of the convent and the chapel. I found the two illuminated buttons—up and down—soothing: there are never as many options as we think there are, and an awareness of that fact should bring relief.

Next Sister Anna showed me the cloister, and, spreading out her hands, the old course of the latticework that once stood as the border between the two worlds.

“We would sit here, and visitors would sit over there. The priest would even take our confessions through that grating, and we’d talk with guests through it—can you believe that? As late as the sixties. We felt as though we were animals in God’s zoo. Each year a photographer would come to take our picture—through the screen.”

She showed me the photographs, displayed in thin little frames that hung tightly packed together, one after the next, all featuring a group of women wearing habits, posing. Some sat, while others stood behind them. In the center was the mother superior, who always, by some miracle, looked a little bigger, a little more solid, than the rest. The latticework cut across some of their bodies, though it seemed the photographer always tried to prevent it from passing over their faces. The farther back in time I went, going down the hall, the more nuns there were in the pictures, the more distinct their habits and veils became. They took over the space in such a way that by the end the women’s faces were like grains of rice scattered over a graphite-colored tablecloth. I examined up close those faces that no longer existed and envied them the fact that every single one of these women had had one particular day in her life when God had spoken to her, had told her that he wanted her all to himself. I had never been religious and had never felt—even remotely—the metaphysical presence of God.

The convent was founded in 1611, when two Capuchin nuns from the north had arrived in this mountain valley that was near a small village. They had secured safe conduct from the pope, and they had adherents among the wealthy. Over the course of two years, they managed to raise the money, and in the spring of 1613, construction began. First there was a small building with cells for the sisters and an administrative section, though this latter expanded at a dizzying pace. A hundred years later, the whole area—the valley and the forests around it—belonged to the nuns. A small town grew up around the convent, partially dependent upon the convent’s economy. A fine location on the lake, along the road, meant that trade flourished and local residents got rich.

The rules allowed some of the nuns, called external sisters, to maintain even intensive contact with the world; the rest, the internal sisters, did not leave the cloister and only very rarely appeared behind the latticework like the unpredictable, mystical force behind that eternal game of tic-tac-toe. Huddled under their cornettes, those cloistered sisters stayed in a state of never-ending prayer, their lips continually moving, their bodies clinging slavishly to the wooden floor of the chapel, sprawled out in the shape of the cross. They were defenseless against the stream of grace that ensured that alpine place uninterrupted good fortune in commerce and the nuns perpetual growth of the convent’s holdings. Perhaps it was upon these devout interns that God’s eye rested, inside that triangular crack in the heavens that would later wind up on the one-dollar bill.

The externs conducted the convent’s business, their fingers stained from the ink in which they dipped their pens as they entered into their books the latest deliveries of eggs, meat or linen, or as they broke down payments made to the construction workers building the new shelter for the elderly and indigent or to the cobblers who made the orphans shoes. Sister Anna told me about all this as one narrates a family—attached and affectionate, forgiving her ancestresses their sins of small-mindedness, their exaggerated interest in making deals. The convent expanded like a fantastically prosperous commercial enterprise and came into the possession of the entire terrain below it, all the way to the lake. The fall of that religious family didn’t occur until the twentieth century, after the war. The town was bulging at the seams, increasingly in need of more land for villas and public buildings, and people were losing their faith. Since 1968, the convent had seen no new nuns, with the obvious exception of Swati. When Sister Anna had become prioress in 1990, there had been thirty-seven of them.

As a result of sales intended to shore up the diminishing finances of the convent, its huge holdings dwindled, and as of today, they consisted exclusively of the one building where the sisters lived. The rest of their land had been leased to several farmers, with cows grazing it now. Their garden was tended by the owner of a health food store; in return for vegetables and milk, the sisters permitted the use of the convent’s name on the products he sold. It turned out, too, that they recognized only too late the possibilities arising from the mercantile blessing that was convent recipes. That pie had long since been divided between the Benedictines, the Cistercians, the Fatebenefratelli and others, who, sensing potential competition from the nuns, banded together in masculine solidarity and made sure the sisters had no share there. They also failed to transform the convent into a profitable co-op. The separate building next to the church was surrendered to an elementary school, while the littler building by the garden now contained a hostel overseen by the town. It was thanks to the monies paid to them in rent that the sisters were able, the previous year, to install the glass elevator to the second floor, since it was harder and harder for them to get up and down the narrow stone stairs. Now, several times a day, they could be seen crowding into that glass box, covering the yards that separated first from second floor.

As she recounted all this, the prioress also showed me around the convent, omitting no nook. I followed her, inhaling the fragrance of her habit—it smelled of the inside of a wardrobe that for many years had hosted lavender sachets. In the pleasant sense of security she gave, I was ready to be convinced to just stay here for the time I had left, instead of sticking electrodes to children’s skulls. It felt as though the air around Sister Anna was vibrating, like she might be ringed by some warm halo. If only she could catch it and distribute it into jars—they’d no doubt make a fortune that way.

She led me briskly down squeaky-clean hallways redolent of floor polish, crowded with doors and mezzanines and alcoves holding shiny saintly statuettes. I got lost fast in that labyrinth. I made sure to remember the galleries of ancestral portraits, the prioresses who looked so much alike they might as well have been clones, and the inscription over the entrance to the inner chapel, hewn in thick Schwabacher: “Wie geschrieben stehet: Der erste Mensch Adam ist gemacht mit einer Seele die dem Leib ein thierlich leben gibt: und der letzte Adam mit deinem Geist der da lebendig macht.”111 Corinthians 15:45, in the Bible’s New International Version: “So it is written: ‘The first man Adam became a living being’; the last Adam, a life-giving spirit.” The floor creaked beneath our feet as our fingers slid over the smoothed spins of handrails and handles become, over time, the inverses of palms.

Suddenly we were on the second floor, in something like a large loft space. The wooden floor was worn to the bone, though then I wondered if it had ever been painted. This was where their laundry dried; amidst the racks draped in sheets and covers, I caught sight of Sister Beatrix and Sister Ingeborg. They were sitting with needles in their hands, reattaching buttons lost in the wash. Their arthritically gnarled fingers struggled nobly with the buttons’ holes.

“Salve, girls,” she said to them. “What do you say, is she ready to meet Oxi?”

At this the old nuns livened up considerably. Frail Sister Anna even squealed like a little girl. Sister Anna went up to a little white curtain that looked innocuous enough, and in one practiced swoop had shoved it over and revealed the thing inside.

“Ta-da!” she cried.

A moderately sized recess was revealed, and in it, a figure, its shape unmistakably human, though shrunken and somehow inhuman at the same time. Scared, I took a step backwards. Sister Anna laughed, pleased with the effect she had achieved. She was clearly used to reactions like mine, and clearly amused by them, as well.

“Meet Oxi,” she said, gazing at me watchfully but wearing an expression of triumph on her face.

“My God,” I said heavily, in Polish. The expression on my face must have been a strange one: all the other sisters now burst into laughter, too.

I saw the body of a human being—more precisely, a human being’s dead body, a skeleton, or maybe a mummy, sat straight up and elegantly decorated. Following my momentary terror, I began to perceive it more precisely, while behind me the sisters kept on chuckling.

The entirety of the skeleton was covered in hand-knit, braided adornments. Sticking out of the eye sockets were great semi-precious stones; resting atop the bare skull, a decorative cap, beaded yarn crocheted. Around his neck there was an embroidered stock tie of thin batiste, which must have been snow white once, now sullied, like a tuft of filthy autumn fog. Here and there his desiccated skin showed through from underneath the fabric of the clothes he wore, though these were mostly covered by a mercifully long and exceptionally ornate eighteenth-century jacket, with ashen-silver patterns that looked like the scribblings of frost on a window pane. Lace cuffs stuck out from sleeves, almost concealing the curved and clawing hands in their arm warmers of disintegrating yarn. Arm warmers! Twisted legs encased in white stockings jammed into wrinkled slippers with metal buckles, also adorned with semi-precious stones.

*

We always strove to follow the recommendation that researchers not become emotionally involved in their relationships with the subjects of their research. That principle suited me just fine. I would only see the children during testing. The young people followed their instructions scrupulously. They were well-behaved kids. It was only during the projective part of the test, where they had to use their imaginations, that several of them had trouble understanding what to do. Then the brainwave tracking session began, and because we were also keeping track of them while the children were sleeping, each of their rooms had to be equipped with the appropriate device, which would in each instance also need to be set up. For over a week I went nowhere, only glimpsing summer’s efflorescence from my terrace as I breathed in the herb that brought me such relief. On a fairly regular basis, Victor started joining me, which meant that my medicinal supplies were running out at an ever-higher rate.

Victor told me during one of our many talks that the convent was facing closure “for biological reasons,” and he told me the story of Swati.

In her wonderful, childlike naiveté, Sister Anna had read somewhere that the presence of the sacred had not diminished in India, whence the winds of history and the smoke over Auschwitz had not yet carried it away. We were sitting on the balcony of my room, resting after moving around all our devices. Victor gazed at the glowing tip of the joint and suddenly felt guilty:

“I can’t keep smoking up your stash, I really can’t. This is part of your treatment. It’s pure pleasure for me.”

I shrugged.

“Why India? Where did she get that idea?”

“Well, if you must know, I’m the one who put it in her head,” he said after a moment. “I told her that if there was any real spirituality left anywhere in the world, then it must be in India. That God had relocated there.”

“Do you really believe that?” I said without thinking. The smoke that came out of my mouth formed a beautiful sphere.

“Of course not. I just wanted to give her something nice to think about, to calm her down. What I didn’t take into account is that she would always rather act than think. And just like that, all by herself, at the age of seventy-whatever, Sister Anna set out for India, on a recruitment trip for the convent.”

I could well imagine it—Sister Anna in her gray summer habit standing before a Delhi mosque, amidst the rickshaws’ uproar, amongst the stray dogs, the holy cows, in the dust, in the mud. It wasn’t a vision that cracked me up, exactly—marijuana had long since ceased to make me laugh—but Victor was guffawing.

“She went from convent to convent, hundreds of miles, trying to find novitiates to bring back with her to Europe. And all she could poach was Swati. Can you imagine? She went hunting for nuns, in India!”

*

The next day I got their files on my desk. They were neat, economical and professional. They contained all the data about the children we were testing, which I had requested from Victor. Right away they struck me as strange. Instead of names, the files were labeled with symbols written on Post-Its: “Tr 1.2.2” or “JHC 1.1.2/JHC 1.1.1,” and on in the same vein. I looked over them, astonished—I was sure they had not been intended for my eyes, that Victor had brought me these files by mistake. I couldn’t understand the meaning of the code. Apart from the tables of biological parameters, there were genome tables and charts that I also couldn’t even begin to comprehend. I tried to glean from those analyses the identities of the kids under my care, but the graphs and tables made no sense to me at all—they must have been descriptive of some other, more abstract plane of truth. That must be it, I thought, Victor must have just gotten mixed up, giving me not the documents I was expecting, but rather something else. As I carried the files to his office, however, a sudden impulse brought me back, and I recorded those strange designations in the margins of an old newspaper. Then I thought I might as well take note of dates of birth. Victor’s office was empty when I set the files down on his desk. The wind in the open window rustled the slats of the blind, and it sounded like a chorus of cicadas.

The following morning, I received on the internal server the information I had been requesting for so long—the interviews on environmental variables and the biographical data. Each file was now under last and first name only. Thierry B. Birthdate: 12/2/2000. Legal guardians: Swiss. Location: small town. He was a school teacher, she was a librarian. Allergies. A detailed layout of his brain studies, with mild epilepsy detected. Blood type. Basic psychological tests. A journal kept by his adoptive parents: methodical but fairly uninteresting. Dyslexia. A detailed layout of his braces. Writing samples. Photos. Schoolwork. A normal kid, being subjected to constant, thorough medical exams. Nothing about his biological parents. Miri C., 3/21/2001: same. Precise charts of her weight and height. Some sort of skin ailment—pictures, diagnoses, et cetera. Adoptive parents: middle-class, he a small business owner, she a painter. Childhood drawings. Numerous references to some other documents, meticulously numbered, classified. The twins Jules and Max, birthdate 9/9/2001. Birthplace: Bavaria. Adoptive parents: businesspeople, owners of some textile factories, upper middle class. Mention made of certain perinatal complications, hence the low Apgar score in both. Jules had a superb musical ear, was attending music school. Max had been in a traffic accident when he was seven—hit by a car, complicated leg fractures, average musical abilities.

Before I could think about what I was doing, my hand had reached out for the previous day’s notes around the edges of the newspaper. I found the twins’ birthdate under the codes Fr 1.1.2 and Fr 1.1.1., and from there it was easy enough.

Adrian T., born 5/29/2000, code—based on that date—Jn 1.2.1. From Lausanne. Adoptive parents: officials. The boy had had problems with the law. Background and environment interview. Police report. The incident had involved breaking into a swimming pool, some property destruction. Several siblings. Eva H., code Tr 1.1.1. Adoptive parents divorced when she was nine years old. She was brought up by her mother, a teacher. Great student, on the basketball team. Interested in film. Writes poetry. Musical abilities. Treated for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

I scanned, amazed by the level of detail in the reports, X-rays of ordinary adolescent lives from so many angles it almost seemed as though these people were being groomed to become spies, or geniuses—or the ones who would start the revolution.

*

Sister Anna gave me lease to photograph Oxi—every little element of him immortalized in his ongoing process of decay. I had the pictures developed at the drugstore in the little town, and I put some of them up over my desk. Now all I had to do was glance up in order to admire the artistry of many generations of nuns who had, with the buoyancy of children, colonized every square centimeter of the corpse, striving to conceal the threat of death. A button. Some lace. Drawn thread work. Decorative stitching, appliqué, tiny pom-pom, cuff, little collar, some ruffles at the neck, a sequin, a bead. Desperate proofs of life.

I was told at the pharmacy I would need to wait a few days to get more of my medicine, so I quietly figured out a way to find a local dealer, from whom I purchased several portions. They were strong, powerful—I had to mix them with tobacco. Since the chemo, the pains had all but disappeared, but there remained my fear of them, twisted up somewhere inside me like metal springs that might at any moment burst forth and rip apart my body, leaving it in shreds. When I was smoking, they metamorphosed into paper snakes, and the world got full of signs, and things distantly removed from one another seemed to be sending one another information, particular signals, linking meanings together, tying up relationships. Everything gave everything a knowing wink. It was a very satiating state for the world to be in—you could take your fill of that world. I went through two rounds of chemotherapy, and I couldn’t sleep. I could not regain control over my own body—the only strength I had left was the strength of my fear. The doctor said: from three months to three years. I knew it would do me good to concentrate on something, and that’s why I came here; not only because of the money, although in my situation, that kind of money might turn out to be the thing that could extend my life. Conducting my tests didn’t require I be in especially great shape. I could do it almost automatically.

Now, every morning, while the children took their classes, I would get up early and head down to the convent. On one such day, towards the end of May, I saw, sitting alone at the edge of the soccer field, Miri. She told me she had gotten her period, and that she’d been dismissed from PE. I noticed she was wearing blue—light blue jeans, a light blue shirt and light blue sneakers. She was the color of the sky. I didn’t know what to say. I simply took a step towards her.

“You seem sad,” she said, a touch of combat in her tone. “All the time, even when you’re smiling.”

She had caught me in the act, as in solitude I had been dismantling my face’s usual expression of self-confidence. I looked at her small, light, almost avian body, which slipped nimbly off the fence, almost giving the impression of weightlessness. She said she wished she could go home now. That she missed her parents and her dog. There she had her own room, and here she had to share a room with Eva. She had always yearned for siblings, but now she saw she found other people to be a nuisance.

“You’re looking for something when you test us. We’re also trying to figure out why it is we’re here. I’m smart enough, I can put two and two together. I suspect it has something to do with the fact we are adopted. Maybe we’re carrying some type of gene. What is it you see when you look at us? You really see something so strange about us? What could I have in common with the others? Nothing.”

She walked with me a while, and we started talking about school. She was going to music school, she played the violin. She also told me something interesting: she liked days of mourning—and these were coming more and more often now, with environmental disasters and attacks—because then the media would play only mournful music. Often everything irritated her, and she felt the world was too big, so those gloomy days were a kind of respite. People ought to dedicate a little bit of thought to themselves. She loved Handel, particularly his “Largo,” which Lisa Gerard had once sung. And Mahler, most of all what he wrote when his children died.

I smiled without thinking. Such a melancholy girl.

“Isn’t that why you’re drawn to me?”

She walked with me until we reached the place where the horses grazed. Along the way she ripped off dandelion heads and scattered the still-soft seeds, premature, into the air.

“You wear a wig, right?” she said suddenly, not looking at me. “You’re sick. You’re dying.”

Her words hit me square in the chest. I could feel my eyes filling with tears, so I turned and started walking faster, by myself now, down to the convent.

*

My late mornings in the convent, when the children had their classes, tended to soothe me. I would feel good in the company of these women, who were both conciliatory and reconciled to life. Over coffee, the sisters’ inefficient fingers separating out their miniature waste restored order. So it would be, too, with me: soon fingers would strip me down to my primary components, and all that had comprised me would now be put back in its own place—a kind of final recycling. Of the cream for the coffee, following this ritual of absolution, there would be parts that no longer had anything to do with one another, becoming separate, falling under different categories now. Gone were taste and consistence. Gone where? Where was that thing that just a moment ago they had still made up together, harmonious?

We would sit in the kitchen, where Sister Anna—often vanishing into digressions, only to emerge again elsewhere—would respond to my somewhat prying inquiries. I never knew where the braided locks of her memory would lead us. In those moments, she would remind me of my mother, who talked in the same way—meandering, weaving together many strands; this was a wonderful malady of old women, covering the world in one vast quilt of stories within stories. The silent presence of some of the other sisters, always occupied with some small task, caused me to take these nuns as guarantors of truth, time’s accountants.

All of Oxi’s information was recorded in the convent’s chronicles. At my request, Sister Anna finally agreed to seek out the corresponding volume. Now she splayed it atop the table in the kitchen where we drank coffee.

She found the exact date: February 28, 1629. That day, the sisters and all their denizens crowded down the southern road into town, awaiting the return of the envoys from Rome. Just before dark, a modest retinue of men on horses appeared from beyond the mountain, behind the retinue a wooden wagon fitted out with colorful, if somewhat soiled and soaked material, beneath which, attached with leather straps, lay a coffin. What was left of wreaths trailed behind the wagon in the snow; the men were frozen and exhausted. The crowd, led by the Bürgermeister and a bishop invited expressly for this purpose, symbolically presented the saint with a key to the city. Boys in white surplices sang an endlessly practiced welcome song and—since this all took place in a disgusting winter month, and there were no flowers to properly honor and receive such an extraordinary gift—spruce branches were thrown under the wagon’s wheels.

That same evening a solemn mass took place. Then came the announcement: Saint Auxentius would be put on display after mass on the following Sunday—in other words, in three days’ time. Until then, the sisters’ task would be to tidy and ready the relics, to put them in order after their long, hard trip.

The sisters were eager to peer inside the coffin. But the sight that greeted them was one of horror. Instinctively, they recoiled. What had they expected? In what sorts of wonderments had their imagination attired this martyr whom they had never even heard of before? What could they have expected to see, these poor Capuchins, freezing in their cells without heating, in arm warmers tugged down to cover parts of their chapped hands, in thick wool stockings underneath their habits?

A muffled sigh of disappointment escaped up to the chapel’s ceiling. Saint Auxentius was just an ordinary corpse, albeit quite dried out by now, sort of neat, and slick somehow, although his bared teeth and empty eye sockets were certainly sources of terror, or, at the very least, revulsion.

Sister Anna said three days turned out not to be enough. Since that time the subsequent sisters had tended to the body of the deceased for over three hundred years. They’d tamed its terror with affectionate nicknames, little jokes and decorations. She herself had crocheted him cuffs when she was young still, since the ones he’d had had all but disintegrated with age. That was the last time the saint’s outfit had been altered. Swati, in spite of her vow of obedience, refused to refresh the mummy’s wardrobe, and Sister Anna had been unable to fault her for this.

Once I was back in my room, I got online and stayed on for a while. I learned that when in the sixteenth century Rome had begun to be intensively expanded, digging the foundations of new homes had often revealed Roman catacombs, and in them, human remains. It turned out, of course, that like any old city, Rome had been built upon graves; now the workers’ pickaxes broke through the tops of tombs, letting daylight seep into them for the first time in many hundreds of years. People also began breaking into the catacombs, their inflamed imaginations shrouding them in mysterious tales. Though who but Christian martyrs could it be, buried there?

Evenly distributed along the shelves, the dead were reminiscent of some valuable good, bottles of the finest wine, maturing over years in order to attain its particular qualities. The dead were no longer bothered by time’s acts of entropy, the destructive part of it that turned human faces into skulls and human bodies into skeletons. Quite the opposite: once bodies had shriveled and rotted, they moved on to a higher order, getting more delicate, no longer causing the disgust of a corpse in the midst of its disintegration, but rather, as mummies, inspiring admiration and respect.

The newly discovered necropolises posed a problem. There were efforts to rebury the remains that had been removed from them, but their numbers were too great—all lovely, well-preserved mummified bodies and elegant skeletons, complete, arranged in graceful poses. The eyes soon grew accustomed to their sight, and then—as was usual in humans—started to differentiate and distinguish the most special among them, the most beautiful, the most harmonious, the best preserved, and from the revelation of their particular beauty it wasn’t much of a leap to their acquiring, on account of the same, exceptional value. In one letter, the stern and gloomy Pope Gregory XIII deliberated over this unexpected abundance of the dead: “We feel as though this whole army has arisen from the ground in these challenging times, and we, instead of repaying it this service, shove it back down into the darkness of the grave. In today’s times, terrible for the true faith, as apostasy closes on us from every side, and of no use are fire and sword against the hideous heresy of Lutheranism, the dead, too, could go to battle…”

These words in mind, one of the papal officials (which of them exactly is not known; there is talk of a Father Verdiani, much-trusted by the pope, and with a pretty good nose for profit) found employment for thousands of the dead. Soon a special office was established; gathered in it were highly promising, highly capable and highly imaginative clerics. Also brought in were special task forces of nuns, silent, hunched over, who patiently cleaned off the corpses of all that had settled upon them over the centuries. All this work was kept under the strictest confidence.

And then the saints were ready to make their public debuts, carefully arranged in modest coffins, cleansed of dust and spider webs, of weeds and clumps of earth, neatly covered in swathes of clean fabric. Each came with a registry book that contained its name and origins, a thoroughly transcribed biography and the circumstances of the martyrdom, as well as attributes and the range of the martyr’s posthumous acts to indicate what type of intercession one might request of it, what types of prayers to send its way. Every saint had his own attributes, his own domain, just like the protagonists of video games today. This one provided courage, that one luck. This one interceded on behalf of drunkards, that one combatted rodents…

Orders from all across Europe poured in. Every supplication sent to the pope and every appeal to his supreme sacred power quickly tied into a request for a holy relic to be sent, in exchange for some reasonable offering. To the plundered churches, which were trying to get back off the ground after their rape by the Protestants, such a relic lent immediate prestige, brought the crowds in under the sanctuary’s roof and enabled them to immerse themselves in the glow of long-lost holy martyrdom, reminding them that this early world is nothing in comparison with the Kingdom of the Lord. And that memento mori.

The process of rehoming holy Roman martyrs was one that lasted many years. The office-workers, those capable, imaginative clerics, went out into the world and became nuncios and cardinals, while the hunched-over nuns died off with quiet sighs. Popes changed, all falling into the past like the pages of a calendar: Sixtus, Urban, Gregory, Innocent, Clement, Leo, Paul and Gregory again, all the way up until Pope Urban VIII. In 1629 the office for rehoming saints still existed, and in an effort to improve their work, the scribes had made up cheat sheets in the form of tables and inventories. Their purpose was not to repeat too often the same torture methods, causes of death, circumstances, last names or attributes.

The next day, Sister Anna told me that she had once been amazed to hear the story of a saint from a church at some several hundred miles’ remove from the convent here. All of a sudden she felt awful: that other saint, whose name was Rius, had a life story and a martyrdom strikingly similar to their own Auxentius’. Evidently the authors of the registry books had run out of ideas. She said, too, that she had once come across a certain work, written later, in the twentieth century, that had discussed the phenomenon of Holy Roman martyrs in a scholarly way, and from reading it she had learned that over the course of all those decades certain trends—if the term could be permitted—had come and gone, some coming back into fashion again and again. For example, towards the end of the sixteenth century, there were a lot of saints impaled in just a few years, and each time the description of the torment was so vivid and juicy, the literary talent of the anonymous office-worker so great, that any reader would experience pangs of horror as they read. At the same time, the female saints tended to mostly suffer the same fate of having their breasts cut off, these then turning into their attributes. In general, they held them out before their bodies on a tray. In the second decade of the seventeenth century, decapitations were popular. Severed heads would miraculously seek out headless bodies, and miraculously they’d unite.

“You’re a psychologist, after all,” she said to me, “so you must understand them perfectly, these inventors of martyrdoms. Even in coming up with the worst kinds of horrors, there must be a little bit of pleasure to be found for the writer, right?”

I said I thought the mere awareness of the existence of this whole realm of the world that was worse than the lot that had fallen to us could be healing.

“That itself ought to inspire out greatest, inexpressible gratitude towards our Creator,” she replied.

With time, the names became increasingly eccentric—of course the reserves of the more popular, more common names had long since been exhausted. Now there were women saints like Ossiana, Magdentia, Hamartia, Angustia or Violanta, and among the men there were Abhorentius, Milruppo and Quintilian, as well as Saint Auxentius, who, early on in the spring of 1629, made his way to the convent.

*

“Do you know what they’re doing up there?” I asked Sister Anna the next time I went down to the convent, pointing to the Institute, visible through the window as a high-up speck.

They had heard they were doing some important research. But that was it.

We were folding bedding, using a technique well known around the world, wherever there were duvet covers, pillowcases and sheets—we stood opposite one another and stretched out at a diagonal those great rectangles of linen and cotton so that they’d regain their shapes after washing. Rapidly, in tandem, we established a whole ritual: diagonal at first, then creases at the sides and smoothing them out with short, fast tugs, followed by folding them in half and then diagonally again, in order to finally take a couple of steps towards each other and thus put the bedding into an elegant package. And then again.

“We have a hunch about what’s going on, but that’s not the same as knowing,” she said. She always spoke of herself in the plural. After all these years, her identity was monastic, collective. “Be easy, child,” she added, and it sounded almost tender. “The church always wants what’s best.”

Oxi gazed at us with his eyes that were semi-precious stones sticking out of his sockets, padded with completely faded silk meant to resemble eyelids. His crimson eyebrows, made of gems, were raised in a cool surprise that was verging on suspicion.

*

By night, the internet led me down other, even more garish paths, whether I wanted it to or not. The posthumous histories of the saints, or rather, that of their earthly remains—the adoration of fingers, bones, locks of hair, hearts ripped out of bodies, severed heads. The quartered Adalbert of Prague, distributed in relic form amongst churches and monasteries and convents. The blood of Saint Januarius, which regularly underwent enigmatic chemical transformations, altering its state and properties. And also thefts of holy bodies, parceling out corpses as relics, miraculously multiplying hearts, hands, even the foreskins of a tiny Jesus—sacrum preputium. Archived pages of an auction site were offering pieces of the bodies of saints. The first one that really jumped out at me was a reliquary with the remains of John of Capistrano, which were available on Allegro for the price of 680 zlotys.

Finally, I found our hero from the attic drying room. Saint Auxentius the martyr had been a lion coach whose lions had been fed Christians under Nero. One night one of the lions spoke to him in a human voice. And the voice was that of Jesus Christ himself. It wasn’t written what the lion said in the voice of Christ, but by morning Auxentius had converted to the Christian faith, released the lions into a forest outside of town, though he himself was captured. The former executioner was now the one condemned to death. The lions were all caught again, and Auxentius, along with other Christians, was thrown to them to be devoured. But the lions wouldn’t lay their paws upon their former master, so in the end he died by dagger, at the hands of an assassin of Nero’s, while the lions were slain with swords. After his death, Auxentius’ body was spirited away by Christians and buried in secret in the catacombs.

*

“I just stood in front of the hotel, afraid to take another step,” said Sister Anna.

We were sitting in the big empty kitchen. The other nuns had already gone out of the room, and gone, too, were the meticulously separated remains of their morning coffee. She’d perched on the windowsill and looked remarkably young.

“It was steamy and hot—about what you’d expect for India. My light traveling habit stuck to my body. I felt like I was paralyzed, because what I saw was terrifying me.” For a moment she was silent, searching for the words. “The enormity of that poverty, that desperate struggle to survive, that cruelty. Dogs, cows, people, the rickshaw drivers with their fierce dark faces, the crippled beggars. It all seemed to be endowed with life by force, against the will of those creatures who were condemned to life, as though that variety of life were a downfall, a punishment.”

She turned to the window, and then she said, without looking at me:

“I think I committed the greatest sin there, and I’m not sure whether or not it’s been forgiven, although I’ve done penance for it, of course. The priest who heard my confession evidently didn’t understand what it was I’d told him.”

She looked out the window.

“The sacred that had been promised me was not present there. I found nothing that might justify all of that pain. What I beheld was a mechanical world, a biological world, like an anthill organized into established orders that were dumb and inert. I discovered something terrible there. May God forgive me.”

Only now did she look at me, and it was as though she were seeking affirmation.

“I went back to the hotel and just sat there the whole day. I couldn’t even pray. The next day, in keeping with the plan, some sisters from a convent outside of town came in to get me, and then they took me to their place. We drove through a dried-out orange space filled with trash and shriveled, dried-up trees. We kept silent, and I think the sisters understood what I was going through. Perhaps they had been through it, as well. Somewhere along the road I noticed some little hills going along the horizon, each fifteen yards or so from the next. The sisters told me it was a cemetery for holy cows, but I didn’t get what they meant. I asked them to repeat it. They said that there the untouchables brought the corpses of holy cows so that they wouldn’t pollute the city. They would simply leave them in the scorching sun and let nature do its thing. I asked if we could stop, and I went up in amazement to these mounds that I expected to be remains, skin and bones dried by the sun. From up close, however, you saw something else entirely: twisted, half-digested plastic bags, brand names still legible, shoelaces, rubber bands, screw-tops, containers. No organic digestive fluid could take on advanced human chemistry. The cows ate trash, and unable to digest it, they carried it around in their stomachs. That’s all that’s left of the cows, I was told. The body disappears, eaten by insects and scavengers. What’s left is what’s eternal. Trash.”

*

I went to say goodbye to the sisters a few days before my departure. I still needed to sort through some papers, pack up the equipment and make my final calculations. The last image I made sure to retain from the convent was the sight of the old women pressed into the glass box of the elevator heading up for mass—Bosch’s lady denizens of paradise making the journey into the beyond, the ends of time.

Returning to the Institute, walking in the balks as I made my way uphill, I got an idea, clear and simple, a matter-of-fact response to the questions that had been plaguing me since my arrival, the questions no one had been willing to answer, which all boiled down to: what was this testing I was participating in like an obedient, well-paid soldier? And my thought was at once simple and insane, which made me believe it might actually be correct. I remembered the innocent question Miri had asked that first day, when I had gone to meet them: “Didn’t you want to clone him? They say they do it all the time in China.”

I spread out the children’s folders in front of me and lit my joint. I looked at their birthdates, provided with hour and place, as though part of the test involved giving them their horoscope. Who knows, maybe that was part of the plan as well. I added, in pencil, those mysterious codes to each date, each last name.

All the testing itself had already been done, and I’d already sketched out their profiles. I was just waiting on the final data, which I usually received in graphic form as a dozen or so prognostic lines, more or less similar to one another. The computer would calculate all the characteristics and then crystalize them around the axes it created for them. The basic graph was thus a kind of tree with branches of differing widths. The fattest, most fully realized branches were the most probable ones. In my time I had seen trees that looked like sprawling baobabs with hundreds of twig-possibilities. I had also seen those that were dominated by a single thick branch. But it was always children—fine, bright, human children—transformed into vegetable forms.

I flipped through the files, sorting out the data groups, when suddenly I was seized by pain—the pain I knew well by now, that reminded of itself from time to time, like a kind of guard overseeing things, keeping them in order. Then, on the verge of pain, just before the arrival of the relief I anticipated, the files and symbols, dates and labels used to designate the tested teenagers, and the inscription in the convent over the door, and Dani’s smile, the black bit of truffle, and Miri’s eyes filled with concern when she asked me about my dead dog—all of it started to roll in my mind like a ball of sticky snow, and everything it picked up on its way made it get even bigger, even more tightly packed. The matter was becoming clear. I just wasn’t sure what the numbers after the letters meant, maybe the number of the trial or some versions of the experiment. Miri was Cl 1.2.1, Jules Fr 1.1.1 and Max Fr 1.1.2. Hannah was Chl 1.1.1, Amelia and Julia Hd 1.2.2 and Hd 1.2.1, Eva Tr 1.1.1, Vito and Otto JHC 1.1.2/JHC 1.1.1, Adrian Jn 1.2.1. Thierry JC 1.1.1.

So it was simple.

Saint Clare of Assisi, a body with no traces of decay, exhibited since the late nineteenth century in a glass cabinet in the Basilica of Saint Clare. A wide range of relics, well-preserved light hair. Saint Francis, a skeleton in good shape, in the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi. Saint Hedwig of Silesia, another skeleton in fine shape, relics distributed by the Krakow diocese, a bone from the ring finger in a church in western Poland. A piece of a bone of Saint Hildegarde. Bits of the body of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, known as the Little Flower, who never quit making pilgrimages all over the world. And three more I didn’t recognize, but all three could be deduced quite quickly, with just a few clicks. I felt as though, in the game of tic-tac-toe, I was completing my drawing of a small, beautiful circle inside the crucial box.

*

I was packed and ready in the morning, and I had called the same cab that had brought me here over a month before. Awaiting it in front of the school, I saw Miri sitting on the fence. She smiled, and I went up to her. I didn’t say anything because I was too moved to. I just looked at her concerned, innocent child’s face, at her blush.

“Clare?” I finally said, almost inaudibly.

She didn’t seem surprised at all when after a moment’s hesitation I took her hand and laid it on my forehead. It took her a few seconds to fully understand, and then she also touched my eyes and ears, and then she put both of her hands upon my heart, exactly where I needed them the most.

Jennifer Croft is the recipient of Cullman, Fulbright, PEN, MacDowell and NEA grants and fellowships, as well as the inaugural Michael Henry Heim Prize for Translation, the 2018 Found in Translation Award, the 2018 Man Booker International Prize and a Tin House Scholarship for her novel Homesick, originally written in Spanish, forthcoming in English from Unnamed Press in September and in Spanish from Entropía in 2020. She holds a PhD in Comparative Literary Studies from Northwestern University and an MFA in Literary Translation from the University of Iowa.