We’ve always loved apocalypse stories, and perhaps we love them more, now, that the earth is burning. There’s no shortage of voices clamouring to capture our decline, but if I got to choose, the voice of the apocalypse would be Lee Maracle.

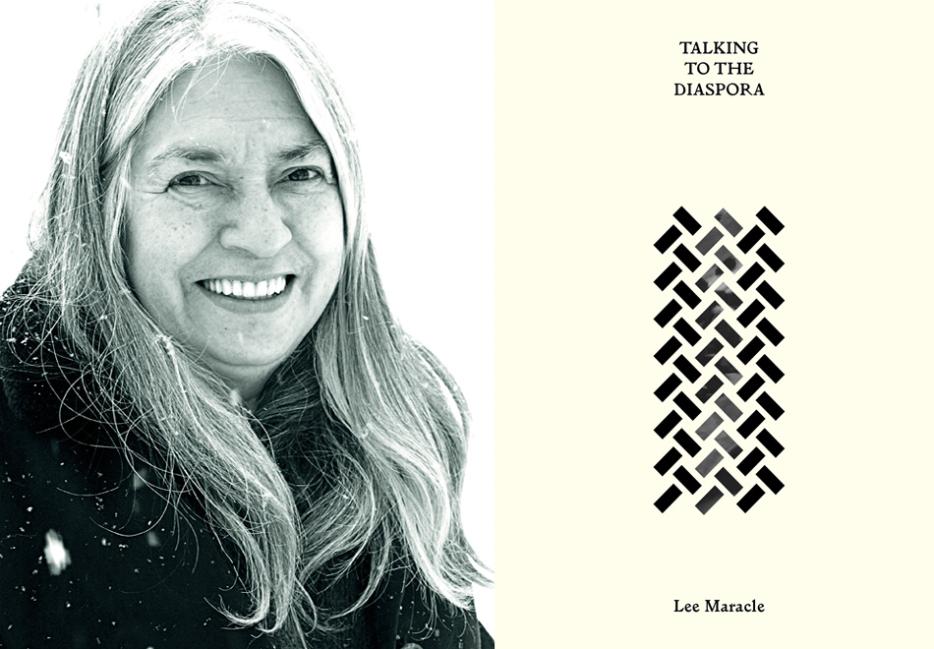

Maracle is the award-winning author of several books, including Bobbie Lee, Indian Rebel, Sundogs and Celia’s Song. She has witnessed her share of destructive endings. The residential schools, the assassination of Martin Luther King, 9/11. All of these moments were the death of something, and all of them find their way into her latest collection of poetry, Talking to the Diaspora.

In the collection, Maracle gives voice to the pain and love that coexist in memory. She holds the two with an equal weight. I would choose Lee Maracle as the voice of the apocalypse because if we listen to her, we might be able to change the ending into something that grows from peace, not anger.

I spoke with Maracle at her office in the First Nations House at the University of Toronto.

Haley Cullingham: There’s a line in one of the poems in the new book, in which you say you want to witness the beauty of a lie.

Lee Maracle: Yes. I love that one. The first time I saw it in a book was Trevanian. I thought he was Basque, because he lives in Basque territory, but it turns out his grandmother was Onandaga, and his grandmother told his mother stories and his mother told them to him. So he’s Armenian, which is interesting enough, and Onandaga, from Canada. And he’s one of my favourite writers—Shibumi, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of it, but if you get a chance to, read it. The Eiger Sanction, which Clint Eastwood turned into a movie. He doesn’t write Native stuff. Except for one story. But he’s longhouse, and it just made so much sense to me, because my grandfather said it. He said, you’ll never understand the truth until you understand the beauty of a lie.

My father got Alzheimer’s, and my half sister—he had two wives—and I went to visit him, and he said, “Where’s your mother?” As though we were the same sister with a single mother. And I said, “She’s busy, dad.” And my sister looked at me, horrified. And I just went, “No.” She’s younger, so she listened. And she walked out of there, “You out and out lied to him!” I said, “Yeah, he doesn’t need to grieve them all over again.” He doesn’t know they’re dead. And one’s been dead twenty years, and the other ten years. So his memory was so lapsed, that he didn’t know his wives were dead, and he didn’t know that we had two different mothers. I said, “All that explaining, just to hurt him? The lie was beautiful,” I said. And she said, “Yeah, it was. I never thought of that!”

Last time, I said, “Daddy, she’s dead.” And he started to cry and he said, “Did I at least go to the funeral?” So heartbreaking. It hurt me, I think, more than it hurt him, because I said, “Yes you did, Dad. You went to the funeral.” He went to the funeral of both women. But that was what I got from that. People demand honesty, which is in the moment, but the truth is, we need to be at peace. And we need to reconcile to ourselves. So sometimes, the lie is better. Makes us more peaceful. And in the story Shibumi, this guy who is chilly, and dysfunctional, and an assassin, finally transforms, and has this epiphany, that he loves this woman. He finally finds love, toward the end of the book. And they bomb his house and blind her. And she’s in the hospital, and she said, “Did they get the house?” And he said, “Yes.” And she says, “But not the garden?” He was building a Shibumi garden. And he says, “No.” And of course, they did bomb the garden. But he thought, she’s going to be in the hospital a year. She will never see it. So he’ll just build another one. And it made her so happy that they didn’t ruin his garden. He felt joy for the first time in his life. So that’s another example of the beauty of a lie. And I think it’s something, about longhouse people, that we understand. That in not saying the truth, there is peace.

Does that mean that there’s room for multiple truths?

No, it means that peace is always what is necessary. That whatever you do, let it contribute to peace. Now, you can get yourself into all kinds of trouble, and our tricksters do, shooting for that and missing. You can lie and get caught.

That happened to me once. My husband did not want me to take my children to the dentist and get root canals. They were too young, he said. So I took them anyway, and I said, “Don’t tell your dad that you went to the dentist.” So then he says, to the youngest one, “Did you go to the dentist?” And she starts to cry! And I said, “Yes she did.” And he said, “You said you weren’t going to take them.” And I said, “Yes, I did say I wasn’t going to take them.” “You lied to me.” “Yes I did.” [Laughs] When you’re caught you’re caught! “I lied to give you peace.” I said, “I lied to give you peace. I was unsuccessful at executing it, and now you are not peaceful.” And he started to laugh. He couldn’t get over it. He would tell people that story. “And THEN she said, ‘And now you are not peaceful,’” and he’d start laughing. And they’d look at him like he was crazy but he enjoyed it so much. When I was caught, I always owned it. I never backed down from myself, and he thought that was pretty funny too, that I had lied, and I had been caught lying, and instead of saying sorry, I just said “I was unsuccessful at making you peaceful. I was going for something and I didn’t succeed.”

He thought I was a very funny person. “You Stó:lōs are funny,” he would say. He was Nlaka’pamux. They were very rigid and austere, and his sense of truth was absolute. There was no beauty in a lie. There is no beauty in a lie. And I was trying to give him peace most of the time. And most of the time I was successful … But if you get caught, own it. And I wouldn’t apologize for it. I would just say that I was trying to make you feel peaceful but I missed the mark. That’s all there is to it, you know? And then I’d move on. And he’d say, “You’re supposed to apologize when you lie.” And I said, “Not me. Someone else! That’d be your other girlfriend.” [Laughs] It would make him laugh. But anyway. He was telling me, not too long ago, “You never brought me peace, not a moment of it, you know?” And I said, “I know, but I was always shooting for it!” And he says, “But you gave me a lot of laughs. I should have just went for that,” he says. And then we laughed some more.

Another quote from the book that I want to ask you about, there’s a line: “Maps are journeys to illusions no one has learned from.” I wanted to talk to you about that in the context of writing fiction. When you write fiction that’s rooted in the world, is that a way of creating an illusion that people will learn from?

I don’t think it’s an illusion in fiction. The stories in fiction have to have happened. There’s a line that we say before we tell a myth, and it goes, “This really happened, even if it didn’t.” That is, it must have happened somewhere. And it’s likely to have happened. It’s the most likely thing to have happened. In fiction, you sit down at the dinner table and things happen at the dinner table that don’t normally happen, but the thing is you’re at the dinner table and it could have happened. Or it happened to someone else. But in any case, you don’t make up stuff that didn’t happen, even if it’s fantastic. Like Raven stealing the light. It doesn’t matter how fantastic it is, it must appear like it could have happened. We just don’t know how it happened. So it’s got to be built in a logical and believable frame. That’s what makes it possible. You have to make it possible. You’re not shooting to trick the person into believing something. If you look at the Rowling books, the Harry Potter, they fly, and they do all this really wild stuff, but if you look at the writing of it, she’s already set you up to believe it. She’s convinced you that it’s possible. And you go on that journey as though it really does happen. So. Fiction is different that way. You have to set it up as though it really did happen. And I think that in doing that, we create a possibility of a greater truth than even the one you started to write about. So it’s different. There’s no lies in fiction.

How do you choose what form a story should live in? Why poetry vs. fiction vs. telling a story verbally?

I very often am not writing a story when I write poetry. I’m mapping out my world of thought and spirit and heart.

So, fiction, you create a world for people to be a part of, and you map it out. It’s terrain, it’s posts, it’s marking posts, it’s topography, the ups and downs of it. But in poetry, I’m articulating the impact of that world on me. My engagement in that world. So a map leads me to somewhere, whether it’s internal as a story, or it’s external as an actual topographical map, I am going from here to there, and this is the way that I’m going. And the map takes me there. Whereas when I’m talking about maps, I’m talking about their affect and their effect on me and I’m engaging them in a different way from within the concept of mapping. And so it becomes sometimes cruel, sometimes elusive, sometimes impossible, sometimes absurd. There’s a whole lot in that business of the map. And it becomes different than fiction, which is the journey itself, and the world of the journey.

What are some things that are happening in writing and activism right now that are exciting you, and what are some things that are worrying you?

Wow, you know, I’m neither excited nor worried about my world. [Laughs] I dip along, you know, I do what I do. I’m excited about a story I just wrote! And it’s a different story than I’ve ever written.

I’m also at the end of an era of writing that I had committed to as a young person. So, the door is open now to writing anything I want. I committed to several different texts, one was Raven Song, which was about epidemics. The other is Celia’s Song, which is about residential school and pedophilia and all that sort of stuff, the double-edged serpent. Daughters Are Forever was about my struggle with my daughters. Will’s Garden was a boy’s story about becoming a man in the Stó:lō world. Sun Dogs was about the Oka Crisis, it was an activist kind of story. So was Bobby Lee. So I committed to those things, and I wrote them, and then I realized that I either need to make a whole new set of commitments, ‘cause I’ve still got twenty years to go, or if I live as long as my dad, twenty-five. I shouldn’t make a face at that. I should actually be excited about that. [Laughs] I’m not sure I want to live as long as Agatha Christie and still be writing.

In any case, you know, I’ve completed the task I thought that would take all my life, and it didn’t, so I got this writing residency, and a poem by Gianna Petrarca came into my head, about looking for my father’s landscapes. And when we first read that poem, my daughter and I realized, the whole of Canada is like that. We don’t have access to our ancestral landscapes, any of us. Because my landscapes have changed. Canada doesn’t exist the way it was. My grandfather used to talk about that, and it would be very upsetting for him. The size of the trees, the gardens, all of that was gone. So we’re in that boat because of the transformation of Canada. But people that came here from somewhere else are in that boat, because different country. Different topography. Different land. Different culture. So nothing is familiar to us.

Human beings in Europe … I was in Poland, and I was in this church that was built in the eighth century. Can you imagine that? Something that old. And how much the Polish people go there, and love that church. And the sound in it was amazing. I started singing “Amazing Grace,” and everybody started singing it in whatever language they spoke. So there was this song rising in multiple languages. Even the priest joined us, instead of telling me to shut up! [Laughs] It was so beautiful. It was such a magical moment. And I wept after, and we don’t have that here. We don’t have it. We have some places that are partially restored, we have a few places that have been preserved, like pickles in a jar, but we don’t have anything that is ours.

So I wrote this story, but it’s a crazy, funny story about these three minks. Then I find out my old-time friend has died. Broke my heart, because I missed his funeral. But I put him in the story, because he’s a storyteller. And he’s a bit of a mink. Minks are ferocious little hunters, don’t have any problem killing things. Well my friend was like that. “Here, whack this fish.” “I’m not whacking that fish!” “Oh, for Christ’s sake. “ He whacks the fish. It screams! “Kootchie, it’s screaming!” “Well don’t listen to it, plug your ears!” But he doesn’t give a rat’s butt, the fish has gotta die, you know? He does a ceremony before he starts fishing, and that’s enough. That’s his only obligation, so that the fish know he’s coming after them. And he picks a male and a female. Takes two mating pairs. He doesn’t take one, ‘cause if you take one, you kill the other anyway. So he does everything the way aboriginal people have been doing it for thousands of years, he takes his little club, gives that little fish a whack, it screams. And it dies. He does the same thing when he’s hunting deer. He still uses a bow. Well, he doesn’t anymore, he’s dead, but he would still use a bow then. And kill the deer, and they’re so beautiful, eh? Skin it, hang it, without compunction, not even think about it, not feel a pang of guilt or anything. I can’t do that, unless it’s crabs. Now crabs scream just as much as a fish, why is that? But it’s what I’ve been doing all my life. The women catch the crabs. The guys catch the fish. There’s an order to our universe. Not for Kootchie, everybody kills the fish! He’s an upriver Stó:lō and we have the same language, but definitely different rules.

So I’m excited about the new book. I’m excited about the new turn in my writing, and it’s a book about the environment, a novel about the environment which was great because it was an environmental reserve that gave me the residency and I didn’t want to do a didactic preachy novel with people taking care of their environment, buncha Indians doing their duty, which we do, but I just think that’s too self-aggrandizing. So, this idea of this little mink coming from the spirit world, and flying through deep space—so it’s kind of a space story, too. I had to research deep space. Did you know that our galaxy is held together by sound?

No!

Yes! I think that’s frickin’ awesome!

That is amazing!

That’s amazing! And black holes make the opposite sound. So, deep space, the galaxy’s held together by low vibrations, and the black hole in space is a high-pitched scream. We can’t hear them ourselves, but that’s the sound they make. I don’t know how scientists know this, but I’m not questioning their knowledge. Scientists know shit. So this little mink flying through space, it’s his spirit, and he has a mind, we have what we call hidden being when we die, we have our memory, we have, you know, all that stuff, we have our heart, our soul, but we don’t have a body. So he’s flying through space flat as a pancake, no real shape. And these two sounds are competing for his soul. That’s gruesome, eh? But it’s funny, too! And then he comes to Van Allen’s Belt. In our origin story, the Sky Woman has to pass through a river of fire. Well, there’s this belt of fire all around the earth. It’s 3500 degrees or some ridiculous thing. It’s very hot, and he has to get through it. Well, he shapeshifts into something cold. I call it a cold-seeking missile, which doesn’t exist but it sounds good. So he gets through that, and he plunks himself down here, and there’s two minks in this little bush staring at him, and he says, “Is this Tkaronto?” And they start laughing at him. “Tkaronto? That’s Mohawk, man. Nobody talks that anymore! Not even the Mohawks speak Mohawk!” and they just kill themselves laughing at him. And he can’t figure out how they could not speak their language, so he starts panicking. “Okay, okay, some of them speak Mohawk. But nobody says Tkaronto, they say Toronto. Torawnna.” Okay, so, he gets that. But it worries him that they don’t speak their language any more, and he said something about, and this surprised me, “Your resonators, your lips, your tongue, your whole body, your very cells are shaped for this language.” You have four communication systems in your body, which I knew before because our people have always known this. But here’s what I wasn’t sure of, and now science knows: it speaks your original language. So, I don’t know, are you Gaelic or anything?

Yeah, Irish and English and Italian.

Well, see, now, you don’t know what language your body speaks. It speaks one of them. It could speak Gaelic, and then you’re in trouble because you can’t communicate with your body. My body speaks Halkomelem. I know because I still dream in it.

So this becomes part of this little mink’s freak out. Like very cell in your body is this language, you can’t not speak your language! I speak mink! What I’m hoping is that people will get that they have to know their original language. And I think that’s why the Six Nations have a constitution that guarantees you your original language. And it’s a thousand years old. So for a thousand years we’ve known this. That the body speaks to itself. And it speaks the original language. It won’t give it up. And that makes me laugh because my old folks used to say, “You know, the body’s very conservative. It doesn’t want you to try things. But the spirit is a revolutionary. It wants to just go!” So if you’re not communicating with your body, you won’t take care of it. You have to appease the body by making a logical plan. And that’s feeling/thinking, or the heart and the mind. The heart and the mind consults with itself and figures out how to do this in the safest way possible. And otherwise you’re a child.

I remember getting up on the roof of the shed, and running across the pitch, the point. And I was going to jump down into the hayloft below. I jumped and saw there was no hayloft. And I just had a chance to think, “Tuck and roll.” I did tuck and roll, but my two kneecaps pulled up, and they’re still out of place! So it’s troubles going up stairs. And that was when I was four. So I learned that lesson that you have to think before you do. The mind is a very important mediator. Now my body is hesitant. But as long as I assuage it, and as long as I persuade my body that I will take care of its physicality and its efficiency, then I’ll be okay. And people have always called me fearless, but I think that’s my spirit. I don’t think my spirit cares whether it has a body or not. Do you know what I mean? That’s just what I think, I could be wrong about that. I will take on a monster, and my body will say, “No! We can’t take on a monster! We’re little! Are you delusional?” Like the maps, right? So then I have to make a plan of how to deal with the monster, how to gather other people around. So that we can take down the monster. And I think that [former Canadian Prime Minister] Harper was a monster that we took down. That’s a really good example. I think we fell asleep while he was being monstrous, and then we suddenly woke up and thought, “God, we can’t live like this. We can’t live like this anymore.” So then we all organized each other. That’s how I think things work.

There’s a line in “Where is That Odd Yellow Dandelion-Looking Flower” about the preservation of place. I wanted to ask you where you see the role of art, poetry, in the preservation of place?

Wow. It’s a medicine that I’m talking about. Milk thistle. And how we destroy the medicines in establishing civilized place. So it’s not really preservation of space so much as the wilding of space, the allowing of space to determine its own ecology, and allowing various plants to do what they do for us.

The saying that I’m working with is that, “Eat the plants that grow in your yard, that grow close to you.” Because that’s the medicine you need. But we’re talking about wild plants when we say that. Like I just had a bunch of nettles grow in my yard, and it’s good for arthritis. I’ve got arthritis. So I’m going to eat those nettles, but they just popped up, when this popped up. [Maracle holds up an arthritic finger.] That doesn’t look very good, when I’m doing that to you. [Laughs] So the milk thistle is what I was looking for, and I don’t even know why I was looking for it, the same with a plant we used to use to wash dishes, but we also used it for menstruation, too much blood flow, to settle down the blood flow, or incontinence in old people, and both my daughter and I needed that medicine, and we thought of it, and she pointed to that plant, and I said, I don’t think that’s it, and I looked it up. I don’t remember the name of the plant but it was the plant I used to collect with my Ta’ah, my great grandma, for those things. And she would tell me what they were for in the language, so I don’t know what they’re for in English, which is kind of interesting. But they do pop up in English, every now and then, so my mind must be able to translate somehow. I’m not conscious of it, but it does pop up when I need to know. And I remember her saying that to me. It’ll come back when you need to know.

So I was thinking of medicines when I wrote that, so I don’t really know the answer to your specific question. If you think of medicine plants, and your question, you might discover an answer that’s different than the one I might be able to tell you. I would have to transmogrify your question. I don’t want to destroy your question. I don’t think it’s a good idea, because it’s coming from your point of view, and the English women and Irish women of Europe were medicine people, too. So maybe it’s a medicine person trying to come forward and get you looking at something. Because our body has a memory of all time, and sometimes these questions pop up to get us shifting in a direction. That’s why I don’t want to change your question. But that’s what I’ll tell ya I was thinking of. See what happens. I might have missed the boat, you know? [Laughs] Nothing’s going to happen here, because Lee missed the boat.

Maracle will speak as part of the Indigenous Writer's Gathering at 7 p.m. on Friday, June 10th at the Bram & Bluma Appel Salon.

This interview has been condensed for length.