Brett Fletcher Lauer and his ex-wife were newlyweds when he found out she was having an affair. A woman whom he’d never met called: “What I have to tell you,” she said, “is difficult.” So begins Lauer’s memoir, Faked Missed Connections: Divorce, Online Dating, and Other Failures, which traces that event forward and backward through Lauer’s history, to his mother’s, and his own, alcoholism; his parents’ divorce and its aftermath; and Lauer’s attempts at adult connection in a world of singlehood changed dramatically since he last entered it. The book is a hodgepodge of documentation—emails, letters, journal entries, online messages—which reads like evidence in a courtroom where the reader acts as judge. Lauer weaves them all together with sections of tight, affecting prose in which he moves back to New York from the Bay Area, contemplates suicide, is visited by a ghost, and finally begins his reemergence into the world of other people.

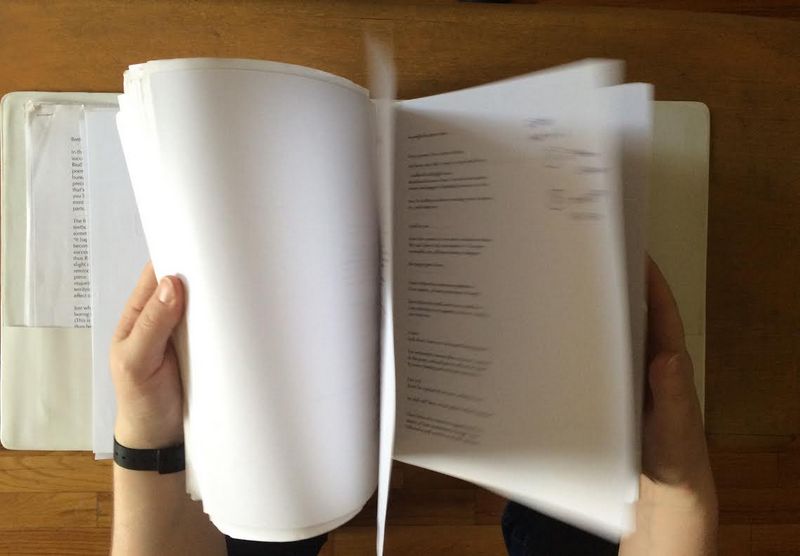

I visited Lauer at his apartment in Brooklyn, which he shares with his second wife, who is Ingrid in the book. Beneath the desk where he works are boxes containing dead pages from the memoir and sentimental papers from his childhood, as well as a file folder holding documents he gathered for the memoir. A poet by training—Lauer is deputy director of the Poetry Society of America and poetry editor for A Public Space, as well as the author of the collection A Hotel in Belgium—I was curious to hear about his experience writing, or rather compiling, a book-length work of prose. We began over coffee, then moved outside for a cigarette, and finally ended up back in the living room. I sat in front of the bookcase where the ghost first appeared.

SG: You put a lot of stock in good writing. But in emails, people aren’t always at their most articulate. We’re either lazy with our writing or we’re conscious that in a moment, someone is going to read what we’ve written, and that may cause us to be more guarded. Whereas in a notebook, you can maintain the illusion that it will never be read, and can write more candidly. You’re combining these two styles.

BFL: I was thinking about this the other day. I don’t know if you remember when people really wrote emails? I don’t get emails that are more than a paragraph long at this point.

SG: No, it’s annoying if they’re longer.

We laugh.

BFL: Luckily, most of the emails I’m reprinting are ones that I was really thinking about because they were either written for someone that I was trying to date—so I was trying to impress them—or they were for my ex-wife, and the nature of that relationship was so fraught that wanting to say everything and say it perfectly and express all of my emotions, I had given some thought to. I’m not embarrassed by any of that. I really love the letters from my father to me, and from my brother to me. I mean, they’re just casual letters.

SG: Your dad is very honest about his feelings and his fatherly concerns for you.

BFL: Absolutely, and those are first-draft letters. Those aren’t typed or anything. I think what’s interesting is that we didn’t communicate as a family face-to-face that way. Those weren’t things that we were saying at the kitchen table to each other. So, there was always a moment or an occasion where it was like, “Okay, I’ll say the fatherly things or the brotherly things that I need to say.” And that might also be because, as a kid I would have been like, “Shut up!” or cried or something. It might have been that they were trying to give me a letter that I would read and listen to, rather than trying to express it in a way where I might get upset or act out.

SG: You strike me as somebody who thinks a lot about time, your own time and time on a grand scale. It comes up in your poetry a lot, actually.

BFL: I think about history a lot, and I also think about religious time. Everything that I read, that is nonfiction, is probably historical: world history or literary time periods. I think I have a very distinct awareness of the time of my life, and of different versions of myself at certain times, and wanting to have a more constant, stable version of myself. But also, a personal history of the time of my family, and my own growth during that period of time, is something I think about. It’s also, as far as poetry, just such a big idea, that a lot can surround it when you’re writing. One of the things that I think about a lot is death. That has to do with time, too.

SG: I wonder how much you think about the future, because you’ve spent a lot of time, as a writer, in the past.

BFL: I think about the future only in the sense of dying. I don’t even mean it to be bleak—that’s just how I think of it. Anything I write comes out that way.

SG: What do you mean, “Anything you write comes out that way?”

BFL: Comes out of thinking about death.

SG: Anything you write?

BFL: Almost everything in some capacity. It’s like writing and thinking about what the most inevitable thing is. It’s not a fear of dying or missing loved ones or anything. It’s just a constant thinking of coming to terms with the fact that at any moment, or at any time … I don’t feel bleak about it. It’s not something I talk about. I don’t have those kinds of conversations. It’s just always in the back of my mind.

SG: The only thing you can be sure of.

BFL: I think maybe that’s it, yeah.

SG: Does it seem silly to fantasize about what might happen before then?

BFL: It seems like a fantasy. Because everything that happens before then is speculative. I’m not speculating how I’ll die. It’s not like, “Will my loved ones be at my bedside?” It’s just more that, this body will stop, and that’s all I know. I think even, in the memoir, there’s that section with the ghost, and I’m having all these suicidal thoughts, and it’s like, “It doesn’t matter. I’m going to die whether I do it or not, so why bother even expending the energy [committing suicide]?”

SG: Can you tell me about the ghost again?

BFL: I hesitate to talk about the ghost becau—

SG: I love ghost stories.

BFL: I love ghost stories, too, and I really want to believe, but I still have a five percent, “Maybe that didn’t happen? Maybe I’m crazy and I was upset and I visualized something?” But it was just here. Right there in that spot.

Brett points over my shoulder, at the bookshelf behind me.

SG: Really? Right here?

BFL: Three nights in a row. Actually, I did see something over Gretchen when she was sleeping once, too. I was wide-awake for that. It was a presence, a shadow. That’s what I mean: I wish something had happened, like someone had said my name, or there was movement, you know? It was really just a figure. Good friends of mine who have ghost stories just have a few more details, to make it seem like, “Of course you saw a ghost.” They went downstairs and the innkeeper was like, “That’s the room in which Maggie killed herself!” [laughs] So, maybe I didn’t, but everything in my body told me that’s what it was. It wasn’t threatening at all. It was actually kind of reassuring.

SG: How was it reassuring?

BFL: It was reassuring to say, “Death is inevitable. There’s nothing you can do to yourself that—life’s just going to take care of that.” The ultimate act of taking your own life, that’s going to happen eventually, anyway. You don’t have to do that.

SG: How did you meet Gretchen?

BFL: Online. We met on a dating site.

SG: Is she in the memoir?

BFL: She’s Ingrid.

SG: Is she comfortable with how she’s portrayed in the book?

BFL: It’s funny, in multiple drafts, right up until the end, they [Soft Skull Press] were telling me that I needed to put more of her in there. I was okay with the book ending—I didn’t want a happy, “And then I met my future wife! Ta-da, you can close the book and we can all feel good.”

SG: You didn’t want a clean resolution.

BFL: No, I did not. Is that something we’re supposed to have in books like this?

We laugh.

SG: I didn’t want that, either, but I knew that not including one would be an unpopular choice. Still, I didn’t want to maintain this delusion of girls with eating disorders just shaping up and eating right.

BFL: Well, my stakes are much lower in telling this story, but I agree. “Oh, you have this really traumatic divorce and you thought this person was the one, and then you date and you find the next one, and that’s how life is?” No, I wasn’t comfortable with that. I was trying to end on a hopeful note rather than a feeling of resolution: It’s hopeful with my mother—but also, just because it’s hopeful with my mother and that might be some kind of resolution, doesn’t mean that when you close the book, that’s the end of the story. I had conversations [with Soft Skull Press] about how much [of Gretchen] I was willing to put in, and how much they wanted, and I think they were right. The book is pretty sad, maybe generically sad: divorce, thinking of suicide, these dating things. To have a breath of fresh air, I think, at the end of the book, is a good thing. To have that hopeful note.

Paper Trail is a monthly column exploring the relationship between artists and their journals.