Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is an enigma. How else might someone describe a 35-billion-year-old time-travelling artist, performer, and storyteller who reimagines, reinvents, and remakes history, art, gender, sexuality, and politics at the same time? She is also the alternate identity of artist Kent Monkman, who paints and performs the sexy and transformational Cree provocateur live and on film in galleries and spaces throughout Turtle Island, or North America.

Every time Miss Chief appears, audiences have asked questions about where she came from, what her motivation is, and why she is here.

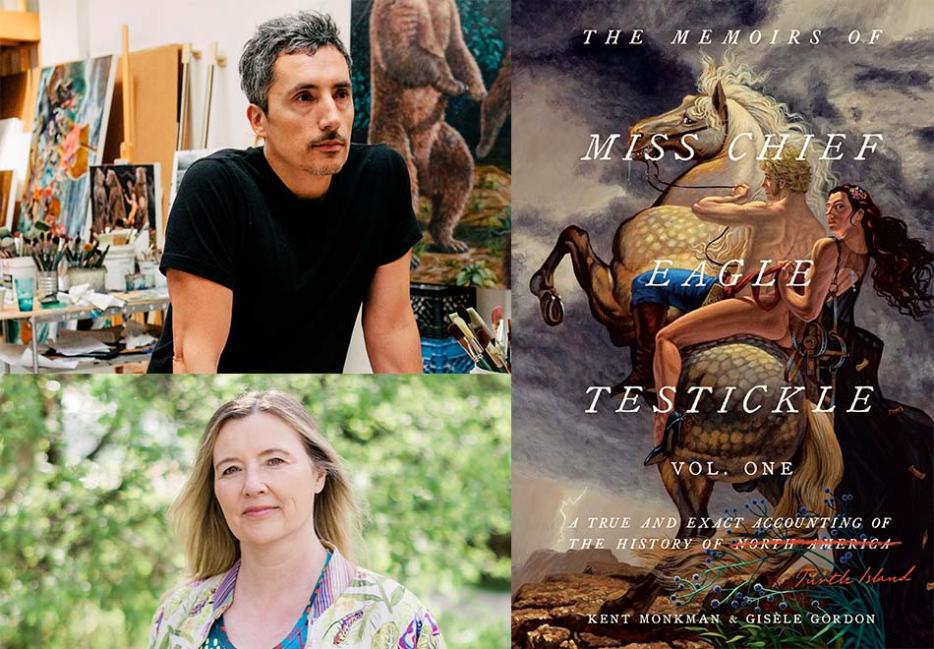

In The Memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle: A True and Exact Accounting of the History of Turtle Island (McClelland & Stewart), we finally have some answers. From her creation story to the present day, Monkman and longtime collaborator Gisèle Gordon have devised a memoir for Miss Chief that is rich, complex, fascinating, and multiple; symbolically coming in two volumes. From her poetic birth to the critical roles she plays in early European contact, the fur trade, the North-West Resistance, Canadian confederation, residential schools, and the displacement and rebirth of Indigenous urban life, the life story of Miss Chief both challenges and crosses boundaries of genre and language. With masterful precision, it also delivers pointed commentary that inspires laughter, tears, and critical perspectives about the connections between Canada and Indigenous communities, while reminding always of the potential of hope and love in the most dire and devastating of contexts. Ending with arguably one of the most beautiful passages in Indigenous literary history, Miss Chief’s memoir is part truth, part legend, part art, part history, part sad, part joy, and all Testickle.

I spoke with Monkman and Gordon after hosting their book launch at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Niigaan Sinclair: Miss Chief is, in many ways, undefinable. Why “define” her now?

Kent Monkman: While I have performed and painted Miss Chief for years, I am still exploring her and understanding her story. For instance, while she is a witness to the course of history as an eternal being, she has also interacted with and experienced things that are distinctly from her perspective—hence, the memoir. To tell her story, I had to spend time with her, asking hard questions that took me a long time to answer, like: Why is she here? What are the limitations of her power? Where does she come from? In many ways, I had to find her creation story—something all Indigenous peoples are curious about. Then, I spent time thinking about her role in history—and why she appears in very specific situations, like during the fur trade, Cree and Métis resistances on the prairies, and in conversations with Sir John A. Macdonald, George Catlin and Paul Kane, and contemporary Indigenous peoples. Creating this book gave me a chance to more fully ascertain who Miss Chief is and how to tell her story.

Miss Chief tells the reader in the opening lines of the book: “My experience of time is different from yours.” What does she mean by this?

Gisèle Gordon: Miss Chief is someone who has been here for a very, very long time, much longer than the 150 years Canada has been in existence. This is why her creation story is so important, something beautifully illustrated in a video we showed during our book tour created by Kent’s nephew James Monkman, a media artist. Miss Chief’s birth accompanied parts of the creation of the universe, the stars, the sun, and the earth itself. She comes from a moment full of inspiration, excitement, and dreams of the world we know and the world we want to know.

KM: After her creation, Miss Chief travels into earth, vowing to return when needed. She lives in real time, of course, but also sometimes goes into liminal, ambiguous time, only to be called back to human time when it’s necessary. Miss Chief has been around as long as space and sound and matter have existed but she is deeply tied to Cree knowledge, which for those who know language and tradition, is full of concepts that resist compression, simplicity, and singularity. Cree time is about interconnection, relationship, and taking the time necessary to get things done in the best way.

Miss Chief exposes readers to lesser-known stories of history, such as the story of Maungwadus and his group of Anishinaabe performers who travelled with American artist George Catlin through Victorian Europe in the 1830s. Is it your interest to educate?

GG: Miss Chief’s story is embedded in her struggles as an artist, storyteller, and dreamer, so naturally she wants to narrate accounts and experiences that may have been suppressed. This is why she is so interested in artists like Catlin and Canadian painter Paul Kane, who have shaped Canadian conceptions of Indigenous peoples and helped create circumstances of our present. By telling the story of Maungwaudus and his performing troupe, we experience what Europeans look like from Anishinaabe eyes and, through Miss Chief, Indigenous eyes too. This exposes subjectivity in all narratives of history and how text, paintings, or museum displays carry false senses of objectivity. I’ve been working with Kent for the last thirty years and I can say that this is my greatest lesson from him and, of course, Miss Chief.

KM: I’ve worked on exhibitions where I’d done extensive research about Catlin and Kane and both have shaped Canadian history (and in particular museums) due to their subjectivity as romantic painters who believed Indigenous people were the vanishing race. When doing research I found their journals and this enabled me to expose some of this bias. When I discovered that Maungwadus also wrote a journal of his interactions with Europeans and Catlin, I realized both were sort of looking at each other from their own perspectives. This is what inspires Miss Chief’s “paint off” with Catlin where she knocks over the easel and walks away—a funny, dramatic, and critical moment when she explores a tactic to challenge and resist racism.

Why is the book split into two texts and divided by Canada's confederation?

GG: Miss Chief’s story has three “braided” strands. The first comes from European and Canadian colonial history and much of the violence against Indigenous peoples embedded in that story. Then, there is Cree knowledge that predates and surpasses that and has been shared with us by the four Knowledge Keepers who were our advisors on this project, Dr. Keith Goulet, Dr. Belinda Daniels, Floyd Favel, and Gail Maurice, who also narrates the audio book, and also in the many texts you can find in our hundreds of endnotes. Then, there is Miss Chief’s story. Braided together, all tell a narrative of a shared history from the past into today and even tomorrow. As you can imagine, this is a long, long story, and after trying to edit it down the best we could we are very lucky that our publisher Jared Bland believed in the project to expand it into two volumes.

KM: When we began construction of Miss Chief’s memoir, we printed out the 300 or so images from films or paintings where Miss Chief appears, and laid them out in a long line—this became the first storyline, chapters and a sort of a storyboard. Then, it became apparent that we had gaps where we needed to connect ideas and stories about her life we didn’t know. That meant we had to tell new stories about her life and I had to paint around three dozen new paintings to flesh out her story.

The most passionate of the many relationships Miss Chief has is with Camille. Tell me about what he brings to Miss Chief’s life.

KM: I really like that you use the word passion to describe that relationship for Miss Chief. Camille is a trans male champion buffalo hunter who fights in the North-West Resistance. He is also someone Miss Chief falls madly in love with. Through their passion, history comes alive. Passion is the spirit that inspires humanity to be their fullest selves. Humans fall in love, they have sex, they fight and resist, they create chaos and they create order; it is through these struggles that we uncover what history is about. This is also why some of Miss Chief and Camille’s most important conversations are in bed after they make love.

Does the fact they fall in love during such a genocidal time in Indigenous history matter?

GG: Telling any story of the North-West Resistance is very hard. It’s a brutal time when Canada committed heinous acts against Cree and Métis communities. While people were fighting for their lives, though, they also found time to love. And in bed, after making love, Camille shares his inside perspective on the resistance with Miss Chief. They found time to assert their languages, cultures, and families and live in the everyday. Their passion for one another and their people drives their actions of resistance—each in their own way.

Miss Chief’s story is a journey that travels a vast universe and ends in a sort of “coming home” when she arrives in inner-city Winnipeg. What does this journey mean and is this a metaphor?

KM: Like Indigenous peoples, Miss Chief doesn’t reside in the distant past but in the present; on reserves, in towns, in cities, and in institutions like universities, art galleries, museums, and community centres. She must be seen in these places. She also exists in me. When Miss Chief comes to Winnipeg, she connects with my roots, my community, and my family as well as interacts with the history of my ancestors and territory. Of course, we fictionalized the people she meets but by stitching her into a real, multi-generational story in this place, she witnesses the fallout of colonial policies and how it impacts a real place. She also comes to Winnipeg because of the land. Cities across the world are built on Indigenous gathering spaces. Winnipeg, for example, is built on Indigenous communities that resided permanently here for centuries in places like The Forks. Miss Chief arriving here reminds people Winnipeg is a real place full of real people and all of it is Indigenous land; not just an arbitrary space renamed by others.

The ending of the book is one of the most inspiring messages for Indigenous young people—and a future Canada—that I have ever read. Despite experiencing and participating in such brutality in Indigenous history, why does Miss Chief end by talking about love, hope, and the future?

GG: Miss Chief’s work, art, humour, and politics are connected to real people. This is why the book ends on real-life portraits of Indigenous peoples, and Indigenous women in particular. By the conclusion of her journey, Miss Chief is transformed. She has become a being full of action, life, and love—something that reminds me of what happened during the days of Idle No More; a time when Indigenous women, men, and Two-Spirit people stood up for communities, collectivity, and to create a better relationship between Indigenous peoples and Canada. The strength of that movement is embedded in the everyday consciousness of Indigenous communities, and especially in the everyday activism of young Indigenous peoples. By the end of her story, Miss Chief becomes a part of everything and everyone, literally connecting the world through molecules of water. She helps us find hope, guiding us towards a better future in a good way.

KM: There are a lot of vulnerable, young Indigenous people out there who are unsafe in their own communities. Through Miss Chief’s voice and story, we're trying to bring better understanding, show how much Indigenous peoples have to offer, and illustrate the crucial work Indigenous peoples are doing when we aren't being denigrated, assaulted, or erased. Miss Chief’s message is that there is hope through resistance, creativity, and art—and this is found particularly in young people who need to know that there is a place for all that they are. I’ve spent a lot of time with Miss Chief and am still learning with her, from her, and because of her. Miss Chief shows us that hope and love is the only path forward, particular in the face of violence and genocide, and we hope others learn from her like we have.