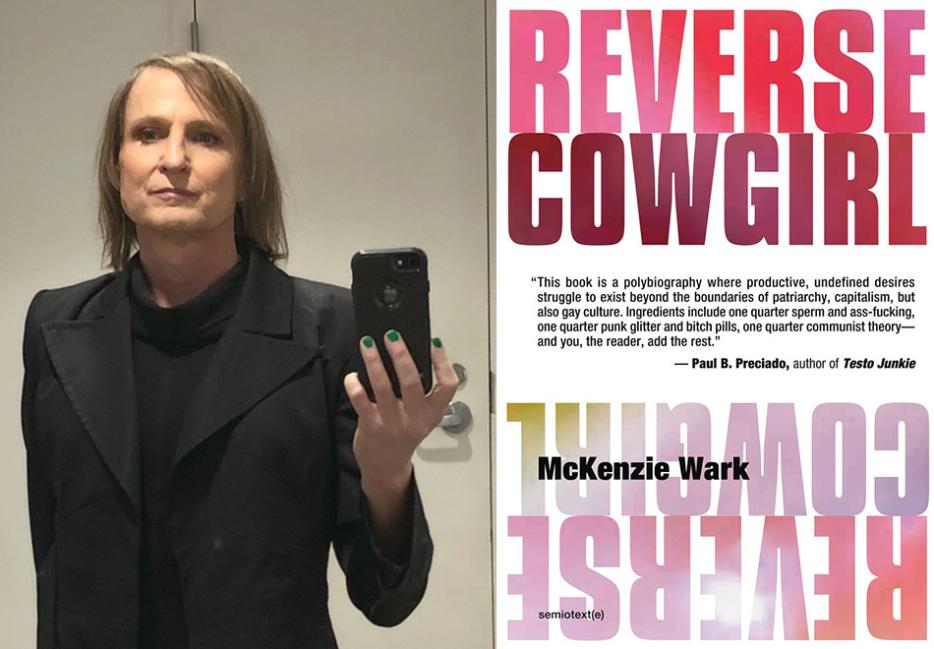

I first encountered McKenzie Wark’s hyper-astute thinking about technology, mass media, culture, politics, and critical theory at university, yet her work exceeds academic territory, taking into account class and labour struggles, as well as the impact of global capitalism. A Hacker Manifesto, Gamer Theory, and Capital is Dead: Is This Something Worse? have all been game-changers in their respective fields, and the 2015 release of I’m Very Into You, Wark’s correspondence with famed writer and artist Kathy Acker, caused a collective swoon amongst Wark and Acker fans alike.

Capital is Dead opens with the query: “What if we asked of theory as a genre that it be as interesting, as strange, as poetically or narratively rich as we ask our other kinds of literature to be? What if we treated it not as high theory, with pretensions to legislate or interpret other genres, but as low theory, something vulgar, common, even a bit rude—having no greater or lesser claim to speak than any other. It might be more fun to read. It might tell us something strange about the world. It might, just might, enable us to act in the world otherwise.” In Reverse Cowgirl (Semiotext(e)), Wark’s latest release, she’s done just that, offering up a new model of a transition memoir.

Constructed as a robust series of narrative reflections, cultural observations, and third-party citations, Reverse Cowgirl addresses the question: “What if you were trans and didn’t know it?” An hour before teaching a class on trans aesthetics at The New School, where Wark is a Professor of Culture and Media, she kindly spoke to me about her experiences of trying to answer this question through writing.

Esmé Hogeveen: Midway through the book, you write: “This is more a meme than memoir. Not a personal essay so much as an impersonal essay. It’s genre less adventure tale than misadventurous genre tail. Not only literary criticism but also critical literalism. It’s not about coming of age, it’s about the age of cum.” Given that autofiction and autotheory are having quite a moment right now, I’m curious if you felt a need to comment directly on your interpretation of these genres?

McKenzie Wark: There’s a tendency to think of autotheory as newly in fashion, but for me, it has roots in Michel de Montaigne, Roland Barthes, Michel Leiris, the later Guy Debord texts. Same with autofiction. Particularly in French literature, there’s a whole vein of writing selves—Marguerite Duras, Guilluame Dustan. I think it’s more interesting, however, to separate out the autofictive from the autotheoretical, and to consider how they become related. Considering how autofiction has become a way to narrate and reflect on non-standard lives strikes me as key. Who are the people who don’t fit the realm of the novel? For me, they’re for whom autofiction exists—where, of necessity, you don’t get to tell stories about marriage and property. And then, next step, to make that conceptual, make it autotheory as well.

I’m curious if you had any sense of Reverse Cowgirl fitting into an epistolary tradition?

An earlier version was epistolary and addressed to people in the book, particularly those who had passed. I couldn’t sustain that, though, and so I turned it into something else. But letter writing was definitely part of the book’s evolution. The novel comes out of the epistolary tradition, and I was interested in opening up questions about how form is invented as you write, and about how a writer shapes the possibility of who the narrator is. I was curious about how that might happen without defaulting into autobiography, novel, memoir, or letter form.

Speaking of form, there’s a turn that happens between the first and second parts of the book that includes a significant gap in chronology. What inspired you to make this leap, and to expose the reader to almost a meta-commentary on writing in Part Two?

When Chris Kraus and Hedi El Kholti at Semiotext(e) accepted the manuscript, there was only the first part and the story sort of ended there. It’s a book I tried and failed to write for ten years. I could finally find a form for it just when I decided to transition. At that moment, the topic I really had knowledge of was being what trans people call an “egg.” I had already socially transitioned when I was working on the book, but I wasn’t on hormones, so I kind of see it as a book that ends before it ends. In one sense, there’s a life that is over, and so able to say certain things about itself. But then something else begins: a really excitable and quite naive trans woman appears in the last few pages. She has an almost mythic point of origin, where everything’s new and fresh. So the book has sort of the opposite of the bildungsroman structure, where you come to the truth of the self at the end. I feel like Reverse Cowgirl ends with this person who has no clue who she is whatsoever, but isn’t bored anymore.

Did writing about growing up in Newcastle, Australia, cause you to reconsider the influence of “home” on your identity? (I’m doing air quotes around “home” right now!)

I quote from one really good book about my hometown (Southern Steel by Dymphna Cusack) and one or two literary friends, but that’s about it. I don’t know how the book is going to play in Australia, because I wrote about Australia in American English. I don’t just mean the spelling—the tone, weight, and meaning of certain words and how they scan doesn’t really have much relation to Australian literature at all. I think the book has a displaced and uneasy relation to place, but I’m kind of a self-hating Australian so that’s all I can say. It’s the expatriate dilemma. But I hope Australian readers might be interested in what an Australian can do within the space of American English.

I noticed the discussion about using Australian “arse” versus American “ass” in the chapter that includes your email exchange with Chris Kraus.

Arse is just not sexy to me. It doesn’t have the same range of connotations as ass. It reminds me of bad British sex comedy, you know? The reason I prefer French literature to English is that it’s much better for expressing sexuality. There are different affordances and a different eroticism and sensibility that, at least to me, aren’t possible in white, English-speaking Commonwealth language. Since I can only write in English, I definitely prefer American English as a language of sexuality, though.

Were there any aspects of your life you were determined to leave out of the book?

Yeah, I won’t write about my kids. The only stuff about my family is really about my parents who are long dead. I generally don’t reveal aspects of my life that involve other people and I’ve hopefully fictionalized some living people enough. The exception would be my partner, Christen Clifford, who was also the book’s first and more thoughtful reader. The book is very, very selectively revealing. I’ve used some pseuds and changed some details, but I’m a little conflicted about those issues. Guilluame Dustan wrote in a serial way that I really like, so there might be a sequel with other stories that lace through and even contradict those of Reverse Cowgirl.

In your last book, Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse?, you explored vulgar Marxism. Recognizing that vulgar Marxism is distinct from linguistic vulgarity, I’m still wondering if you sought to describe sex in explicitly “vulgar” or colloquial language when writing Reverse Cowgirl?

That twin sense of the vulgar might connect the autofiction and autotheory sides of my work. Reverse Cowgirl is about bottoming as praxis, and—why not? There are endless descriptions of fucking in the English language, and the best are in porn rather than literature, frankly, because of porn’s interest in detail and suppression of the metaphoric. When writing, I was really interested in how precisely one could describe, particularly remembered, acts of fucking. The sex scenes were written first and all together. I was alone in a hotel room in Seoul, Korea, and supposed to be doing an art world junket and I just wrote all those scenes.

I felt there wasn’t a whole lot written about the details of an egg-state trans woman's sexuality. As I say in the book, no one needs to read more about a cis man fucking a woman, so I only included one scene like that, which plays for comedy because I’m so disassociated when I’m doing it. So the book is vulgar in that sense, and vulgar in the Marxist sense by being interested in what practices are, and by trying, in a very minimal way, to be honest about who is doing what labour and how class comes into it.

I’m curious if you anticipated that shopping and fashion would be such core themes?

There’s stuff in there about the commodity fetish and the sexual fetish, which again connects autotheory to autofiction, as I had both fetishes at once [laughs]. I was interested in the layering of presentation and how bodies are always erotically and sensorily charged no matter how many layers you’re wearing. You’re never naked in the sense that you’re always wearing an image of yourself, yeah? I was also considering images available in the mass fashion culture of the '60s, '70s, and '80s, so fashion was maybe always going to be there in that I didn’t want to talk about ass-fucking for an entire book. How people appear to each other in everyday life, and how you play with those appearances, is also part of trans experience. For instance, I dressed like a girl through the '70s, and nobody noticed because everything was unisex.

Yes, that comes up in the chapter about David Bowie!

I was trying to recall what it was like growing up in that broadcast culture. There were literally only forty songs played on top forty radio, so you had to find the one song that offered another possibility for how you could exist. You couldn’t go on the internet and find your preferred flavour of being. You had to read through things that were polyvalent and Bowie, for example, was a master of that.

I’m thinking about the moment when you reference the Stuart Weitzman 5050 boots. Iconic!

[Laughter] They’re a bit of a trans girl cliché, I think. You can get them in big sizes, although I’m only a women’s 9—runway model size [laughs].

I really appreciated the Otto von Busch quotes about “feral fashion” that you included.

He’s a colleague here at the New School and he’s always spectacularly turned out. I’ve learned a lot from him. He equates fashion with systems of fascism, thinking about submission to dominant style as being a form of aesthetic fascism. I’m putting it a little more strongly than he would, but the idea reminded me of how I never wanted to be too singular while I was growing up. I never wanted to sign off on dominant fashion systems, nor did I want to be a complete outsider, so it felt like I was always negotiating between the two as you work your style through the fashion cycle. Now I just dress all the time like it’s 1967.

While we’re talking about personal style, I’d love to ask whether writing about fashion being in tension with commodity culture made you feel more or less skeptical about clothing’s liberatory potential?

It’s funny, critical theory in the '80s was about trying to reconcile yourself to being inside closed systems, where any form of play was inevitably internal to those systems. Recognizing that your resistance is what those systems fed off of, you still just tried to extract some possibility of belonging in and against the mass commodity market and its fetishistic surfaces. It’s sort of bittersweet now, because I look back and view my fascination with style as also a holding pattern for navigating obtuse gender dysphoria and not realizing I was trans. So fashion was helpful, but also obscuring.

Did writing the David Bowie chapter, which is a cross between a letter and an essay, feel like a refreshing opportunity to analyze a character other than yourself?

Yes. Bowie is one of the reasons a lot of us are alive. It was really weird when he died and I learned that all these super straight people also felt connected to him. I thought he was for us, but the whole point of pop culture is that it’s for everybody in all these different ways. And Bowie had a certain genius that was all about appropriation. He stole it all, obviously. You can go through the eras and see how he was appropriating and mixing. But yes, he died while I was writing the book, so his death went into it, too. I felt like I could make him a character that would thread from my teenage years to my emigrant New Yorker life. Bowie came to New York just before I did. That’s a thing about this city: it always had these outsize outside characters who populate it as a popular imaginary space. David Bowie was one of them and it’s just nice to know you walk the same streets that he walked, that Candy Darling walked, that Miles Davis walked, and so on.

Several of the book’s key themes seem to crystallize when you write about Bowie. In the “Queen Bitch” chapter, you describe “teenagers of the seventies [who] lived through the great cult of cock.” You write: “[I]f one had a cock, you could try to mimic the simulated cult of it on display in rock and roll. But if you did, and it worked, the girls you fucked were not dreaming of you. They were dreaming of rock stars. You’ve got to be the substitute for the substitute.” Can you talk about this idea of substitution?

It’s from The Who song “Substitute”: “But I'm a substitute for another guy / I look pretty tall but my heels are high / The simple things you see are all complicated / I look pretty young, but I'm just back-dated, yeah.” I remember when that was on the radio, because I’m that fucking old! Those '60s pop songs were like nursery rhymes to me. That was a key song about doubling and replacement. I read it as really being about class, but it contains all sorts of feelings of insufficiency in relation to the idolatry of pop. Bowie came at the end of the era when rock stars were men with big, swinging dicks, and the dick was hidden but supposedly real. It’s interesting how much that’s faded away now.

But then to be the substitute of the substitute is '80s semiotic theory—the endless chain of signifiers, each replacing the other. And Bowie is interesting for how he cut across those eras. We know he fucked under-age groupies. He was no saint. But there’s also a camp reading where you know Bowie got fucked in the ass. There’s a way that Bowie’s personas—and that’s what they are, it’s never him—have little particles of someone who bottomed as well as topped and had a complicated relationship to gender and other layers of being. He’s a substitute for a substitute. He’s someone you sort of know has also done some really bad things, but when you get to Bowie, it’s endlessly substitutable and that’s sort of the point. It struck me that this capacity for substitution is what signifies Bowie as different from the rock gods that came before him, the big "authentic" dicks.

You often invoke Greek mythology, specifically referencing the goddess Ariadne and linking her to Bowie’s spiders from Mars. I’m wondering if references to diverse mythologies felt crucial to Reverse Cowgirl’s project of imagining new selves or horizons?

As I was working on Reverse Cowgirl, I was writing about Kathy Acker. The Acker book is called Philosophy for Spiders and there will be a lot more Ariadne myth in that, having to do with simulation and doubling and mechanical reproduction. So a bit of the Ariadne myth ended up in this book, as well. Kathy thought that myths begin as a sensation of a chaotic universe but then the story of the myth ends with a somewhat artificial re-establishment of an underlying order. In her own writing, she tended to cut out the parts about order. Instead, she gives us myth’s chaotic face in its pure form. So I wanted to include myths that had the first part of the mythic story without the orderly conclusion. I mean “story” here in the Walter Benjamin sense, as in small templates you can use to think all sorts of different things. Like a template for a concept that isn’t specific, a good myth has the function of being able to do a few things at once.

The other myth I played with was another one Kathy worked with: Orpheus and Eurydice. I use Jean Cocteau’s film version. It’s sort of the fulcrum point of Reverse Cowgirl. I felt like I had to include some version of why I transitioned it, but I decided to make it a myth. In my version—spoiler—Orpheus is Eurydice, she is the multitude he contained and can no longer contain. I don’t really care to figure out the origins of my transition beyond that, so myth was useful. My transition happens late in the book, and that last section is where something else begins.

With regards to mythic order, you also write, “In my utopia: before anyone attempts to fuck another, they will first have learned how to be fucked. Irrespective of genders or whatnot.”

This is advice I give to everybody! Especially cis girls whose boyfriends want to fuck them in the ass. I wanted to give a vulgar description of what a utopia might be. Maybe one that doesn’t scale. Perhaps utopias have to be temporary in time and space. A good rave may be the next scale up in terms of what a utopia can be. I might have to write about that in the sequel. But I wanted to include a utopia that has a minimal reciprocity of both difference and connection. That one learns to bottom before one gets to top is my whole sexual ethics. In an ideal world, boys would not get to put their dicks in anything until they’d been thoroughly penetrated. But would that world ever come? Maybe not.

Oh, let’s not rule it out though! Soon after that last quote, you write, “But basically, there are the fuckers and the fucked. I wanted to be, and became, one of the fucked. To become flesh.” I’m curious if you see the positions of “fucker” and “fucked” as always juxtaposed? And, if so, does maintaining space between those positions feel necessary given what you’ve just said about the importance of being fucked being the primary encounter?

I have to admit it’s a whole sexual ontology. I don’t know if I’m like that anymore [laughs], which is a weird place to be in. I’m not sure if that’s me anymore. Stay tuned for the sequel! Trans women’s sexuality is a whole other experience that’s not widely written about, although do check out Torrey Peters, Carta Monir, or Juliana Huxtable, for example.

But yeah, I wouldn’t want to universalize Reverse Cowgirl or claim it reflects anyone else’s experience. One of the things the book is trying to do is to excessively generalize from a very particular kind of experience—my own—to show that anybody is welcome to do that. The details of any autofiction can also be abstracted into its own wonderfully specific autotheory. There’s a point at which any kind of generalizing becomes crazy. All sorts of universalizations probably come from super weird and specific experiences, so it takes a bit of nuance to accept that one could generalize an entire worldview through one concept of utopia and a very particular sexual act. That generalization could be completely persuasive and real for someone who shares that experience and unreal for anybody else. My concept of utopia doesn’t negate anyone else building a different worldview. It’s more fun to try to put them against each other. Maybe someone else has an entire worldview based on non-penetrative sex. There are versions of political lesbianism that are actually exactly that and my worldview doesn’t negate them. It’s just different.

The language of trans-ness doesn’t come until the last part of the book. There’s a great nugget on page 178, where you say, “Since I was already writing this book, I thought about the writing, if ‘thought’ is the right word. More that I felt it. Felt the book in the body, and the body in the world, the book in the world, the world in the body… Since the body felt fine with itself, for once, it felt fine in the world, and the book felt like it could be fine in the world someday, too, or almost.” Was writing the book a process of bidding farewell to a version of yourself?

That’s a whole fallacy around the relation between writing and life. Like, writing doesn’t sum up life at all, as if life happens and then you contemplate it and explain it. I was actually able to go on living by writing the book, not the other way around. It was tempting to go back and change the book once I’d decided I was transitioning, but I didn’t. There were only one or two little tweaks to the music of the text, so the ending doesn’t completely blindside the reader. There isn’t too much teleological foreshadowing going on, at least I hope there isn’t.

Did the moment where you take mushrooms at the lakehouse and come to this full—I think you use the word “giddy”—decision about transitioning happen while writing?

A little bit, yeah! There was a certain element of deciding on a whim, both about the book and about the transition. The Eurydice myth is fiction, but I did go to a lakehouse and I did have a fantasy while tripping up on that hill. But I wanted to avoid imposing too much retrospective consistency onto things that had happened earlier. I wanted the things I thought I really knew about my pre-transition life to stand and to let the much shorter, second part of the book kind of kick that sideways. I go off somewhere else, but I think that’s more what life’s like. I’ve found it a little uncomfortable that the dominant genre for trans writing is autobiography. They tend to have arcs and end with reconciliation. My transsexual life wasn’t like that at all and I think lots of people, trans or not, have lives that don’t add up or make narrative sense, so I wanted to open and expand what happens in trans writing but also for anyone who finds life too accidental to read like a novel or memoir. With a couple exceptions, I didn’t find myself in the literature that was available, so I wanted to open a space for other trajectories.