Twenty years ago, after more than a decade of bereavement, panic, hopelessness, scientific stagnation and institutional intransigence, antiretroviral combination therapy—that infamous “cocktail” of drugs—was made available on a wide scale to people living with AIDS in North America. For the first time since the advent of the epidemic, the number of deaths related to the disease dropped, plummeting twenty-three percent from the previous year’s tally.

For those on the frontlines—the grassroots activists, the lovers and caregivers of patients debilitated by AIDS-related opportunistic infections, the gay men grappling with social stigma and bureaucratic contempt, the health-care workers tormented by their inability to save thousands—the new treatment seemed like a miracle. “How does a population psychologically braced to die suddenly get on with the business of living?” pondered Newsweek staff in an op-ed from that December titled “The End of AIDS?”

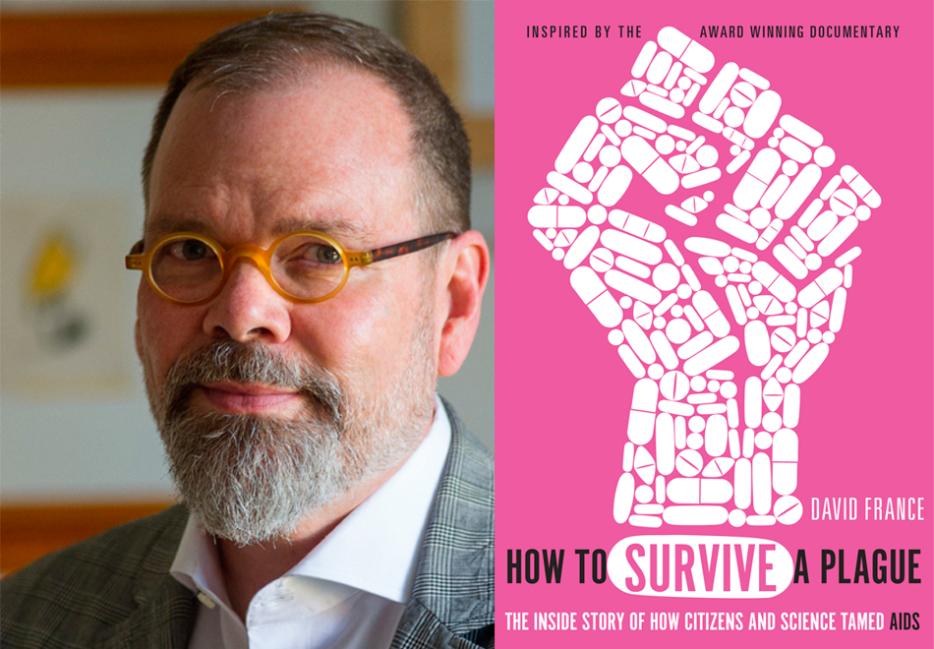

The story wasn’t over, of course: there were still nearly 35,000 AIDS-related fatalities in the United States in that year alone. But that moment, the dawn of the Lazarus effect—the promise held by new drugs that would keep those with the disease alive, at least until another potentially effective therapy was discovered—marks the climax and conclusion of David France’s remarkable How to Survive a Plague. A harrowing and astonishingly vivid account, France’s book is both a complement to and an expansion on his Oscar-nominated documentary of the same name. It’s an extraordinary work of history, one that tells a (if not the only) story of the earliest years of the AIDS/HIV epidemic and the activism that coalesced in the face of tragedy.

Hazlitt: Your original cut of the How to Survive a Plague documentary was thirteen hours long—did the book come out of necessity, out of the desire to include everything that was left out of the film?

David France: Actually, I wanted to write the book first. I'd created a book proposal, as one does, and carried it around, as one does. It was 2008, 2009, and everybody told me there was no market for a story about AIDS, that AIDS was in the past, that there was a glut of AIDS material already. The story had been chronicled.

The plague was over.

That's right. So even if there were additional issues to be parsed, who would care? And my argument, which met with deaf ears, was that all the great work that had been done around the plague, had been done in the middle of it, from Paul Monette to Randy Shilts to Larry Kramer to Mary Fisher. The writing was powerful and terrifying—

And unmediated.

Yes. And a lot of it was very personal, and a lot of it was very rooted in time. Randy Shilts's And the Band Played On was the only one of those canonical AIDS books that reached for history. But there was no interest at all. It was also a bad time in publishing; the economy was about to tank, everyone in print got panicked. And as part of my process to build a book proposal, I'd gone back to that videotape pile….

How much videotape was there?

I eventually brought in 800 hours of mostly home movies. Some people have called it a found-footage documentary, which technically is a kind of category. But this wasn't footage that was inadvertently captured. It was all purposefully recorded in order to create records that were undeniable.

You've been working in journalism for decades. How did the documentary process influence you as a writer and shaper of narrative?

I'm a long-form journalist, so it wasn't a leap for me to work on a narrative storyline in a film with a three-act structure. I think I've always written in ways that are cinematic—or at least anticipate that cinematic feeling. A lot of my work has been made into films. But what I realized was that what I didn't have any experience with was working entirely with visual media, and that was problematic. It was a steep learning curve.

Figuring out which frames to capture, you mean?

Exactly. It wasn’t enough that I found somebody saying something; I had to find them in the context of this and looking like that, and then I had to explain why they were there, in that particular place. I was bound by the historical record more than I'd anticipated in going after this old video footage.

When this footage was recorded in the '80s and early '90s, was there a sense of urgency within the community to be documenting things for history? I remember reading Paul Monette's Unbecoming, which is a kind of reportage—a firsthand account of how the disease caused the dissolution of self—and trying to make sense of who it was intended for.

I think each of us felt an obligation to do something when it became clear that we were all endangered. If you did feel drafted, there were various things you could do. People were signing up for home health-care visitation; there were organizations formed to walk the dogs of people with AIDS and to write the wills of people with AIDS. You'd bring your expertise to it. In 1981, I was just out of college. I was in graduate school. I felt called to write news, to find the news—which was hard to find—and then to bring it back to the community. So I was writing for the queer presses and trying to create medical news and science news that would engender hope. I was looking for the answers. I never found them, but it's what caused me to become a journalist, instead of a philosophy professor or whatever else I was going to become. That was my motivation. I wasn't really trying to create a permanent record of historical crimes.

But Michael Callen was. In 1982, he and Richard Berkowitz sat with their doctor, Joseph Sonnabend, and the doctor saw the tragedy in the future, and he felt a very specific need. He sat with his patients and said something to the effect of, "This is going sideways! Greed and lies are going to drive this. We have no power to correct their narrative, but we have power to gather the truth." And he charged both of his patients with making a record. That conversation is on audiotape.

It's remarkable that these galvanizing moments in the history of this struggle are actually documented.

The first half of the book is all based on audio recordings that people were making, knowing that they needed to capture the undeniable facts of what was happening. The first conversation between a person with AIDS and anybody in the federal government's research establishment was captured on tape. Michael Callen, after that conversation with his doctor, went out and bought his own Panasonic tape recorder for $39—he saved the receipt! Michael’s now long gone; he died in '93, but he took this idea very seriously. At one point he said that one day there would be a Nuremberg-type trial, to bring to justice the people responsible for having let an infection that originally impacted forty-one people develop into one of the deadliest global pandemics of all time. That's what he was leaving behind: the records for that trial.

Institutionalized homophobia persists, regardless of political affiliation. But if AIDS had unspooled under an American government that was at least nominally friendlier to LGBTQ people, would there have been the same impulse to create an alternate history?

So, we got a liberal government in the States in 1992, and it was really no better. When Clinton was elected, there was a lot of hope that it would be better. He said the word "AIDS." He was the "I feel your pain" politician, and that "I feel your pain" line was delivered to an AIDS activist who was heckling him at one of his campaign stops.

You describe that scene so vividly in the book. I can hear his patronizing inflection.

It's on videotape! It's all on videotape! I think there are only a handful of conversations that were recreated from people remembering what they said. There are, like, 80 pages of endnotes citing tape after tape after tape after tape, most of which had never been transcribed before.

What was it like to pore over all those tapes? It's one thing to sift through a general archive; it's another to be revisiting your own history—these were people you knew, a period you lived through. Was it harrowing?

Well, part of it was very heartwarming. To hear Michael Callen again! And to hear the part of Michael Callen I'd never listened to before—there's a New Year's Eve in 1984, ’85, where he's really despairing. He's lying in bed. He'd sent his lover off to the parties because he just wasn't well enough. And he's delirious. His mind is clouded; maybe by fever or infection. And to hear him struggling with that on this tape that he made and put aside, that was really stunning. I mean, he recovered from that night and remained a leading voice in the AIDS movement, even through 1987 with the formation of this grassroots activist initiative. He was a thought leader and philosophical leader till his death in 1993. But almost ten years before that, he was really despairing.

Can you remember the moment when you transitioned from reporting on something that was happening to becoming part of the story?

I never really felt like I was part of the story. I had coffee with Larry Kramer recently and when I gave him a copy of the book to read, I said, "You're going to hate this—initially, at least—but eventually I think you're going to like it." I explained to him that I'd written the book as an outsider. It's full of praise, but I wanted it to be a real historical commemoration of what went right and what went wrong, and how this deeply flawed group of people came together and created this deeply powerful movement.

Now, I decided to include my own story in the book, because I wanted to create a witness account. I was a witness. I was there. I was as panicked as anyone else. I had AIDS in my relationship. My lover was sick. I was not an outsider to the plague, to the epidemic. But I always remained independent as a journalist.

I started out in the queer press, and eventually, I was covering AIDS news for the New York Times. I decided that the role I was going to play was not as an advocate journalist, but a journalist using the recognized tools of independence and objectivity to tell these stories. I was at all those ACT UP meetings; I was at all those demonstrations—but always with a notepad in my hand. ACT UP had no formal membership roster; the rules were that if you went to two meetings, you could vote at your third meeting. And I never voted.

Within such an action-oriented organization, was there a sense of appreciation for your approach? Did people see you as an emissary who was bringing the story to the outside world? Or did they think you should be more involved in the grassroots aspects of the fight?

I never felt pulled in in that way. I worked closely with the journalists who were. There was a journalist who covered AIDS at the Village Voice, Robert Massa. As he was dying, he felt he needed to replace himself, and he began recruiting for people to come and do the kind of work he was doing, which was very aggressive, very critical, very advocacy-based. He didn't come to me. Because...that was not the work I was doing. He approached friends of mine who were, and ultimately, he did replace himself before he died, with Kiki Mason, who stayed alive until '96. After '96, they didn't fill that position again.

So, was there appreciation among them for what I was doing? Maybe there was a little suspicion, even, about why I wasn't doing more internally, why I wasn't speaking in the voice of activism. I've always considered myself a person who covers activism—which I guess is a form of activism.

Andrew Sullivan touched on this in his review of your book, but it's remarkable to have a story with so many bodies on the ground where you resist hagiography. (You're very candid about Larry Kramer, for instance—both his failings and his triumphs.) You were relying on subjects to share very vulnerable, often painful stories, so how did you negotiate that dynamic?

People always spoke to me as a journalist. When I was at the Times, when I was at Newsweek, any of the places I've been able to shoehorn in AIDS stories, I've always been a journalist. I've never been friends with any of these folks. They've often been critical of my work. I've allowed them to be critical of my work; I've allowed that to not change my work if I thought I was right, and I've allowed that to inform future work if I thought I was wrong.

I've been interviewing Larry since the '80s, and always as a journalist. I don't think I've ever sat across from him without a tape recorder or a notepad, except maybe when he was in the hospital. When I started working on this book, he said he would not participate. So I didn't talk to him and ask him to go back in time with me. But I did find that he'd dropped all his papers off at Yale, and I convinced Yale to give me early access to his datebooks, his drafts of speeches.... It was amazing. Three weeks; thousands of pages of stuff. I feel like I could understand him from then. A lot of the warts-and-all stuff about Larry is the stuff other people were angry with him about. I think I'm really clear in the book to acknowledge his seminal role in galvanizing the entire movement around AIDS, even in his imperfect way.

You’re also very candid in writing about the death of your lover, Doug Gould. You describe sitting in the hospital after fruitlessly pleading with Doug’s doctor—any doctor—to help him, and thinking, "Someone needs to do something, and no one is going to do anything." He eventually died of an opportunistic infection that, even at the time, was diagnosable and treatable. After realizing that it was a death from wilful ignorance...

Not ignorance. What's the word? Disregard.

How do you acknowledge that disregard, come out of that experience and not go on a rampage? How do you maintain journalistic objectivity?

Well, it took me a long time. This book is my first attempt to address what happened with Doug. I found that doctor. I sat with him, two summers ago, and asked him to account for what had happened. He was so damaged—and he’s not the only doctor who was damaged by AIDS—that he wasn’t able to make any sense of it. I feel he was another victim of the epidemic.

Did he have any answers? Any excuses? Any explanations?

No, no. He didn't remember. He's had trouble with his medical licence. He was very much a diminished man; he's working in a free clinic these days. He'd been one of the top researchers on the disease. That he's still practising medicine is a testament to his ability to recover, at least partially, from what he'd been through.

Nah, I just think he's a human being. We've read the stories about the concentration camps, about how people in dire circumstances tried and failed to maintain high moral standards. I can't imagine what it would have been like to have been a doctor back then, especially a queer doctor, like he was. To lose so many hundreds of patients every year, and yet there's nothing you can do about it. There was nothing he could do about it—in the larger picture; there was certainly something he could've done for Doug.

Right.

And Doug would've died anyway, I believe. Even if he'd gotten through that infection, he would've died of the next one, or the next one. I don't have any reason to believe he was going to be one of the people to live through the miracle year in 1996 and enjoy the Lazarus effect and go on to have a long career in theatre or whatever else he would've stuck to afterward, realizing he had a life.

As someone who was so immersed in the queer community in New York at that time, what are your thoughts about the generations that have followed—the generations that have a sense that the epidemic is ancient history?

I think there are two different things at play. Yeah, people are still infected, and yeah, people are still dying. But there's great news—the great news is that we can stop transmission, and we have rolled transmission back to really low levels. And we now have even newer tools to help with that. We know that the same drugs that keep people with HIV infections healthy keep people who don't have HIV infections from getting HIV. That's amazing!

So, you're pro-PrEP.

Oh, yes. I'm happy that twenty-somethings don't have the feeling of a sword hanging over their heads. That's what we were fighting for. That's where we got. There are other problems—there's all the syphilis, all the gonorrhea, all the other crap going through the roof. And maybe what we need to do is solve those things medically, rather than behaviourally. Maybe people should be allowed to fuck all over the place, if that's what they want, and to have it be life-giving.

Not long after you made your documentary, there was a real wave of AIDS/HIV nostalgia. Dallas Buyers Club came out; HBO released the telefilm adaptation of The Normal Heart....

This was around 2012? I'm not one to take credit for stuff, typically, but I think that documentary opened up that conversation. It opened up whatever vault we'd put AIDS in. It was 15 years after the advent of those drugs. And there's something about a fifteen-year interval. If you look at literature looking back at the Holocaust, it came about fifteen years after the fact. There's something about the human mind—or soul—that needs some time to pretend tragedy didn't happen, in order to go back and make sense of things.

The work ACT UP did back then really anticipated the way patient advocacy has evolved since then. I’m thinking particularly of how people with cancer have become fiercely engaged with seeking out and arguing for their inclusion in clinical trials. At the time, it was unprecedented to have regular people taking responsibility for interpreting science and agitating for experimental treatments.

It was the advent of citizen science. All the buyers' clubs that started in the early '80s, where they were importing drugs from around the world and making them available to people with AIDS on an underground black market—by 1987, there was a realization that this was not going to do it. There was no way that patients, through criminal ingenuity, were going to solve the problem of AIDS. It had to be the scientists themselves, and they had no idea what they were doing, those scientists. And no one was helping them strategize. So that's what they took on. That was fascinating; that had never been done before. That's what we learned: not just ordinary people, but people on the furthest margins of society, which is where we were in the '80s, could make change. We were in a group that was disenfranchised with glee by everybody else. I've seen old videotapes where politicians were talking about funding AIDS-prevention initiatives and they said, "If we make this capitulation to the gay lobby, they'll come and ask us for marriage licenses." I don’t think anyone was thinking that at the time, but…the guy wasn’t wrong.

A lot of people are worried that the Trump regime will have hugely detrimental implications for HIV/AIDS treatment initiatives, and for people living with the disease—particularly given Mike Pence's antipathy toward anything LGBTQ-focused. What's your sense?

We're all guessing. I find myself going to sleep at night with dreams that the election didn't happen, or that it can be undone. We see a government being pulled together that's anti-science, that's fully anxious and engaged in the old culture wars from the '80s—but also not reasonable, not predictable. There's no single ideology. You can't even believe what they're saying, because they say it differently the next day. So I have no idea what's going to happen. But we all know it's not going to be good. But we don't know where or how or what the battlefronts are.

A Missouri court of appeals just called for a new trial in the case of Michael Johnson, a.k.a. “Tiger Mandingo,” an HIV-positive college student who was convicted in 2014 of “recklessly infecting” a sexual partner. The criminalization of HIV is a hugely vital fight for Canadian activists right now. Is it the same down in the States?

It's a state by state thing. I don't know how the Feds can work on that. But they can withhold monies here and monies there—prison systems, school support—as a way to engineer the adoption of certain policies by states. And there will be nobody discouraging those laws, which are anti-science laws. They're not about the transmission of HIV. They're about sexual behaviour.

And pathologizing groups of people.

There are scores and scores of young men and women in jail for very long sentences, some—or most —of whom didn't transmit HIV. They're there because they didn't say that they had HIV—or they said they had HIV, and their partner, after a bad breakup, got even. You don't know what those situations are. But the point is that HIV transmission is no longer a death sentence. And it doesn't happen in people who are effectively treated.

Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz and Joseph Sonnabend, their innovation was safe sex. Safe sex speaks to the people who are negative—that was the audience—and says you have to just assume that anyone you encounter is positive and you have to have the power to protect your life. It speaks to people who are positive, also—it says we have to show love for the people we're having sex with and make sure that we're not transmitting it. That power has fallen apart. Campaigns around it were never funded. It was never promoted as public health policy, as it should've been. So the person who goes and has unsafe sex who is negative and then discovers the person they had sex with wasn't...that's a person who doesn't love him- or herself to a degree where they want to make sure that they stay healthy. It's a complicated, consensual interaction.

Men who’ve written about the generation that came of age in the time of Stonewall have talked about the lack of role models for loving gay relationships. Your book leaves the impression that that shifted during the ’80s. Given the way that AIDS exposed and added a different kind of urgency to intimate relationships, do you think the epidemic inadvertently provided that archetype—it showed that there could be loving relationships between two men?

I wonder. It certainly really intensified our concept of community—but not just between gay men; between gay men, lesbians, transgender people.... Our world, the queer world came together in a way it never had before, especially across gender lines. But did it create the marrying mind? That’s what you’re asking?

In a way. I’m wondering if it introduced the notion of lasting gay love on a much wider scale.

Well, nothing was lasting then. But it launched an overt discussion about gay love and gay community and gay family. We had come together as a family. From '69 onward, we’d always called the community “family.” And in those years, it was because we'd been rejected by our own families and created new families. In the '80s and '90s, to watch how that family worked together and took care of one another and mourned one another was very moving.

I think it did encourage people to look at coupling in a way that they hadn't before. We see that in Michael Callen's narrative in the book, that he'd never imagined himself in a relationship—and confronting AIDS and confronting death made him challenge the way he thought of his sexual activity, and what he got from sex and what he got from relationships and what he got from love. Maybe it opened up those new possibilities.

How did it shape your concept of love?

In my personal life? I think it made me into a caregiver, which I hadn't necessarily been before. But I was always a long-term relationship person. My last girlfriend was a four-year relationship, and I went from that into these long stretches, some of them stolen away by AIDS, and then after 1996, I've been in a twenty-two-year relationship now. But it's a queer relationship! And we're not emulating straight marriage! But we have our own sort of really profound relationship model that's developed in recent years—at least among men. Women were...I mean, the '70s brought us that joke about what a lesbian brings on a second date: a U-Haul. And then the boys became more like that in recent years than the girls. But we were outlaws for many, many years. And the change in the last decade, to being in-laws? It's a really startling one. Some of us chafe at it, but we're playing along.