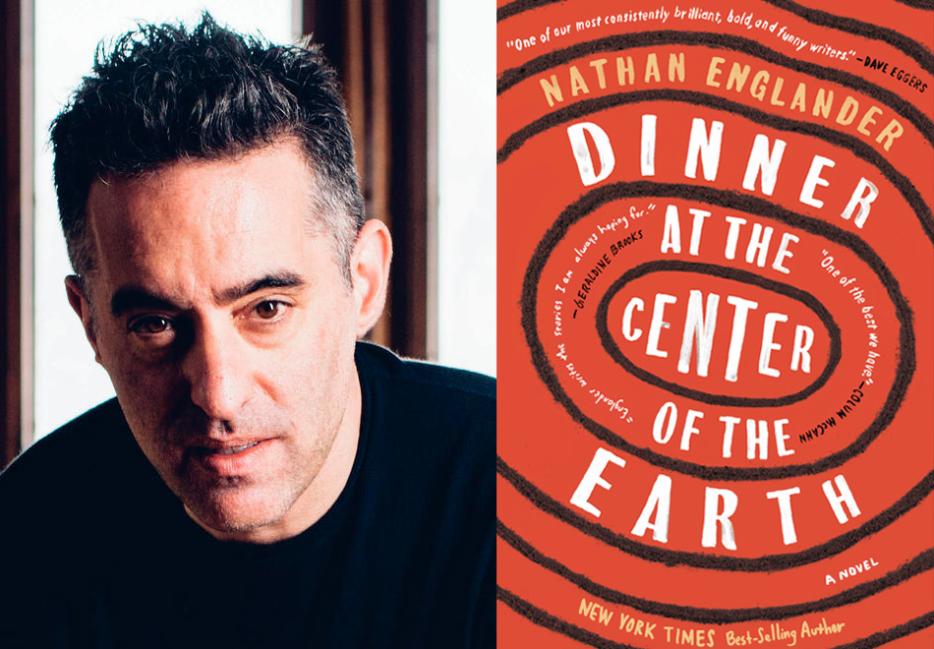

When I first speak to Nathan Englander over the telephone from my French phone number, he quips, “good, good, harder for the N.S.A. to track you”; when I note that he has a newspaper photo shoot after our conversation, he says, “I got my Spanx on already. Now I need a little pancake makeup, and we're good to go.” Englander’s demeanor is not what one would expect of someone whose name is frequently thrown around Pulitzer committees (he was a finalist for his second collection of short stories, What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank), and it’s especially not what one would expect from someone whose new novel, Dinner at the Center of the Earth (Knopf), turns on the Israel-Palestine conflict. But Englander, like his more-than-they-might-appear characters, enjoys trafficking in gray areas.

Born in Long Island, Englander matriculated at SUNY Binghamton before heading to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for his MFA. From 1996 to 2001, he lived in Israel, where the plot of Dinner at the Center of the Earth began to form in his mind. Writing in the New York Times, Rachel Donadio compares the novel’s style to that of John Le Carré, but it’s more akin to something like David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas. Englander writes in concentric circles, his plots taking place in different times and places, moving towards and away from one another, overlapping only once, on the 182nd page. His characters include an Israeli military general, a Canadian businessman, an American waitress in Paris, a Palestinian in Berlin, and an unnamed prisoner in a hidden cell—some of whom are actually the same person or far different from how they’re presenting themselves.

In our wide-ranging conversation, Englander and I discussed the novelist’s responsibilities in times of political chaos, the bending and breaking of structure and genre, the shifting nature of Jewishness and identity, and his ultimate subject: right, wrong, and why we crave it.

Cody Delistraty: You wrote an op-ed in the Times on white supremacy in Charlottesville; your Twitter timeline is rife with American political news; and your book turns on the Israeli-Palestine conflict. What’s your responsibility as a novelist when it comes to modern politics?

Nathan Englander: To start, I've wanted to write this book for twenty years. It's almost part of the heartbreak for me that it's still a very current story. That's the point. That's what has me pulling out handfuls of hair—the endless, obvious cycle of violence that we need to break out of. I'm very sensitive. I think it's very delicate. I think a didactic book or an author who is self-righteous or thinks they know something—if a book is a lecture, it's going to be corrupted. It's just not going to work. I just think conscious intent to convince on any subject is corrupting in literature.

I think that's what makes it so vulnerable—to enter into these things is just to admit that these things are you, and these things are obsessing you. I wanted to explore the politics of it with empathy. The political part is just part of this story. For me, it was an obsession with the futility of these cycles and how to get out of them. It’s a weird political thriller woven into a historical novel with a love story that turns into an allegory that is exploring this conflict and trying to look at it with empathy. I hope that makes some semblance of sense. I know it's deeply political, but my real want was for people to enter into this story, which is literally why it needs to be character-driven and plot-driven.

Also, if you're a writer, it's because literature has saved you at some point. For me, I love that books can explore a notion. It's not offering you the answer to four plus four. It's not giving you the answer to the formula. I like that books are there to raise the question. They're interactive. That's the point. I'm not interacting with four plus four. There's only one way out of that, which is eight. (Which gets us into American politics, which now says four plus four can be seven because I said so—or eleven.) But I don't think I'm offering a singular conclusion, except maybe trying to embrace hope or optimism. The only position is that we shouldn't all kill each other. Maybe that’s a position. There is such a thing as right or wrong even if it's challenged. To say Israeli and Palestinian peace is the only option does not seem to me a radical position to take politically.

Does fiction have a heightened responsibility right now, given the particularly divisive nature of politics in America?

Well, first, I don't know in history if we've ever before had a president who doesn't read. But I can't answer your question as a writer. I can answer it as somebody who reads a book and takes something away. I think part of art's goal is that it doesn’t have a goal. That's the point. I really want to stay away from—have you spoken to anyone who, in three short minutes, has said “that's the point” more times?—the didactic. I think it's about shared consciousness; that’s what art does. As a reader, it broadens me. It allows me to reach outside my own world. I don't think it has a specific politics purpose in that way, but I do think people who are involved in politics, people who change the world, I do think that their only concrete action is to make people think differently or at least to share. That's shared consciousness for me, and I do think that changes us.

I can answer this question in the reverse, which is to answer why totalitarian regimes and why demagogues go after writers. Who's a poet threatening? Who's a fiction writer threatening? The demagogue notices that power. It’s a subversive form that an idea of someone else, something that is extraordinarily, impossibly different from your ideas, can enter into your consciousness and be lived through a book. I think that does foment change, but I never would be so hubristic to think that that's my book's goal.

I was reading through Granta’s Best Young American Novelists issue, and there were just one or two stories that directly grappled with American politics. Is there a problem with novelists of my generation—millennial writers—when it comes to addressing politics?

I always think there's a wave of something. If you look at book cover design, there will be a killer cover, and then there will be a wave of iterations of that cover. Any idea that people are staying away from politics, there's somebody out there who's doing it. I'm not worried about a shortage of political fiction in that way. You have to write what is in your mind. It’s why I'm a huge Orwell fan. Why do his books work for me? It's because they’re about what's torturing him. It's what he's engaging with. It's what he's wrestling with. That's why it reads as literature and why I feel like it can foment change or expand consciousness. It is an act of sincerity. It better come from the heart. It's not about choosing to write about politics.

As you mentioned, your book is at once a political thriller, a love story, and, as I heard it called, “an absurdist farce.” What led you towards this kind of genre-mixing and -bending?

I've been wanting to write this book for almost twenty years, and it’s so huge and comes with so much baggage tied to the subject. I promise you, if you screw the book shut with a drill and hold it up for people, I promise you they'll have a position on it. There was this Baltimore rabbi who said something like, “My brother's book is a terrible book, and I'm not going to read it.” This subject is going to come with a stance even before anyone cracks the cover of it. That's why I really felt like it had to be so character-driven and so plot-driven. In terms of the political thriller part, it was a story through which to explore the conflict. I can't even tell you how those things enter into your consciousness, but when I thought of it I said, “Yes, this is the way to tell this book. This is the only way to tell this book.” I wanted for it not to be moving into the politics, but moving through a story that contains the politics. It was also twice as long. I cut it in half. I really wanted a book that people could sit down with. That's why I wanted us to just move through it. Drive through it. I can't speak for it myself, but it has a momentum built in.

The novel is also written circularly, in which various stories over various timelines overlap and pass one another. What does that structural complexity add?

I always say don't lend a writer money. Don't trust them to babysit your kids. Don't lend them your car. Writers are personally messed up in so many different ways, but to write a book, a system of weights and measures where your heart is, it better be in place. I think that's what I mean. I come to this with such big positions. Yes, I wanted the story to make the decisions. As I said, I wanted those swings. You already know this—god help you, I'm glad you're taking it—but I speak in circles. I think in circles. My sentences circle. I literally write them and then unravel them so they're in the right order. To me, I think I also waited my whole life until now. Nobody ever starts. It's always somebody avenging right from a previous wrong. Things build up. There's a huge explosion. There's a loss of life. Then peace is made, and then people start to rebuild. Everybody on both sides is already preparing for the next Gaza invasion. That's insane to me. They have an invasion every few years. You know what I'm saying? The rockets will start flying. Again, that's already political. I start with the rockets, not with the invasion. That's my point. Pick a side, and you'll start the story wherever you want. To me, that's the madness of history, that it's repeating itself so mechanically. That's why I wanted the spirals through the story so that we swing back through consciousness, swing across time. You have a story told in a linear manner, but I just want to push to each edge of story and then swing back because I feel like that, to me, mirrors the cycle of this conflict.

I read this interview from five years ago, and I know you aren’t keen on getting questions related to your Jewish identity, but—

That's funny. I feel like that's totally changed. I feel like I spent twenty years like that, and now it’s totally different. As a fifth-generation Jew, with my great-great-great grandparents coming over, I thought it frustrating that I have to have this identity thing. Like, why do I have to be hyphenated, you know what I'm saying? No one says “Christian novelist John Updike.” He gets to be American. Now, I’m happy to be the Jew. In the current political climate I'm wearing fifteen yarmulkes right now. I’ve never wanted to be more hyphenated; I embrace it. That was so important to me before, and it's so weird how this moment is changing all of us.

I was talking to Michael Chabon about this recently too, but with that embrace of your Jewishness, do you think Gentiles ever miss or misunderstand fundamental parts of your writing?

Wow, what an excellent alley-oop of a question, just the one-two punch of it. You couldn’t ask it better, but I guess the answer is that if I were to teach a class on Voltaire, someone would be like, “I want to give Candide to my friend, but he's not French. He hasn't been dead for 200 years. He's never been disemboweled like Cunégonde.” Everyone is Game of Thrones crazy. “Oh, can I give this book to my friend? She's never sat on top of the iron throne. She's never seen a dragon.” It’s a very sweet thing that comes from a good place at readings, where someone will come up to me and say, “I'm Jewish, but I'd like to give this book to my friend who isn't. Do you think they can read it?" I feel if a story is working, it one thousand percent has to be universal. I love Moby Dick, and I've never been whaling, so I feel like it's only with that hyphenated thing that we ask this question. That being said, I'm sure there are plenty of great books that are just meant for someone who's holy—that if you're not a religious Jew you're not going to get them. If you're not black or gay or French or whatever, you’re not going to get it. Every story speaks specifically. It's tailored to your individual experience. I don't even think it's about culture. I think every reader has his or her own unique experience. I love the neuroscience of it. That's the point. Everybody’s chin has to hit differently. I'm a dog lover. A dog shows up in a book, if you're dog-phobic, you're going to have a different reaction. But you say “dog,” my heart melts.

What do you consider your ultimate subject?

It's fun to talk to you. I feel a shape to our talk that comes in the nicest manner. I think for this question, it comes back to the whole identity thing that we’ve been talking about. When I started out on this book, I was still against the questions like “You're a Jewish writer... whatever.” But now, for me, that’s most of what I see: Jews everywhere, Israel everywhere, Jewish culture—all that stuff—and it’s led me to become obsessed with the black and white and the gray space. My subject is justice and injustice. These epical, moral questions around justice and right and wrong and my real hunger for there to be a right and wrong. We all have anxiety in these current times, but the notion of truth being deconstructed is so disturbing to me and so evil. I would say, for me, my subject is really about how we exist. You're probably like, "Even your answer is Jewish—really angsty and existential and Jewy.” But that gray space, that’s what I'm fascinated by.