Every Sunday members of the Hazlitt staff and the occasional guest share what was notable about their week—online and off.

Jordan Ginsberg, Senior Editor

I sleep like dogshit. Well, to be specific, I fall asleep like dogshit. Once I’m out, I am cadaverous, but getting to that point and shutting down can be an ordeal. This is not a new phenomenon: I started tossing and turning when I was six years old and never really stopped. Mostly it’s fine, the swollen baggy eyes and unpredictable lengthy pauses in conversation (Editor note: Yeah, it's been noticed) while I try to remember who and where I am. Though in my dumber moments I’m still sadly prone to lamenting how tall my doctor told me I was supposed to be before the devil of sleep-deprivation stunted my once surely unstoppable rise to six-foot-greatness.

And yet, there are benefits. When the war comes, I will be an invaluable watchman/target. Sometimes, I forget what people’s voices sound like. Also, I got to watch a lot more TV than my friends when I was a kid. As an adolescent insomniac living in Toronto, though, my late-night viewing options were severely limited. This is how I came to love Night Walk.

This week, Jimmy Fallon signed a deal with NBC to take over The Tonight Show from Jay Leno next year, opening up a nightly hole at 12:35 a.m. for the network. Oddball speculative candidates such as Tracy Morgan, Dave Grohl and the Archer team are all fine and ambitious choices for the slot, and yet, they are ultimately foolish. The late-night talk-show format is a relic and growing more irrelevant by the day. Do the right thing, NBC: Strap a GoPro to some intern’s head, set him loose across America after sundown, fire up the slow jamz and give the people what they want for an hour a night. Take it from me! I haven’t slept in days.

*

Christopher Frey, Editor-in-chief

My favourite thing on Hazlitt this week was Alexandra Molotkows’s Minutiae column “Suicide and the Art of Living,” in which the improbable pairing of Plasmatics singer Wendy O. Williams and French artist-writer Edouard Levé—both suicides—prompts a rumination on art, memory, and self-murder.

“I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining. We do not remember, we rewrite memory much as history is rewritten. How can one remember thirst?” — Chris Marker, Sans Soleil

That so much of Alex’s story was about memory squared nicely with the fact I’ve been lately re-immersing myself in the work of Chris Marker, in anticipation of the film and photography retrospective being jointly mounted by TIFF and the Contact Photography Festival in May. Among the highlights on the film side is a screening of his rarely seen 2003 essay Remembrance of Things to Come about the photographer Denise Bellon. In it, Marker cites André Breton (whom, as a fellow traveller of the surrealists, Bellon photographed): “If a man has learned to think, it hardly matters what he is thinking. At bottom, he is always thinking about his own death.”

Which, no doubt, brings me to The Shining. Thanks to Michelle Dean’s story on Room 237—the new documentary that drives a Borgesian worm hole via the many disputable hidden meanings of Stanley Kubrick’s horror film—I was tipped off to this wonderful making-of doc shot on set by the director’s daughter, Vivian. I was only ten years old when The Shining came out, so it was a few more years until I actually watched it on VHS. But I did see the trailer, which gave me nightmares for months. It’s a one-shot of the hotel’s elevators disgorging a tsunami of blood that fills the corridor in menacing slo-mo until it washes against the camera’s lens. (The other film-inspired nightmare of my youth was the final scene of Superman: Lois Lane buried alive in her car in the California earthquake triggered by Lex Luther. There you have it, there’s me—elemental nightmares, drowning in blood or earth.)

Earlier in the week Michelle reported from an on-stage interview Aleksandar Hemon gave in New York to discuss his new memoir disguised as essay collection, The Book of My Lives—which I am presently reading. Hemon is the one novelist working today whose writing should be studied by journalists; there’s his voice, and there’s that The Lazarus Project is a model of documentary fiction. I haven’t arrived at the last essay of the new book yet, “The Aquarium,” but am equally excited by and dreading the moment when I do. It was previously published in the New Yorker—where I read it already—and tells the story of his not-quite-two-year-old daughter’s death from a rare form of brain cancer.

Evidently a Hemon fan like me, Michelle emailed when filing the piece: “Man I like that guy. Fire all the white male Brooklyn unsure postmodernists I say and replace them all with people who have real problems.”

Maybe with all this death around it’s no surprise that the dark magik of Black Sabbath’s album Paranoid has been the go-to soundtrack for the week.

*

Britt Harvey, Assistant Editor

I think Roger Ebert is the first “celebrity” death I’ve really cared about. Wait, scratch that and add Nora Ephron to the list. I don’t say that to be callous, but there’s only so much emotional room you can make for complete strangers who you’ll never meet but with whom you’ve conducted whole conversations in your head.

Ebert made me want to be a writer. It’s as simple and complicated as that. His spare, uncompromising, and at times brutal prose, seemingly effortless. Like someone sitting you down and telling you all the things you didn’t want to hear while ever so gently squeezing your palm. Sometimes I would close my eyes after reading his reviews thinking, “now that’s it.”

His work was so unpretentious and lacking in fatuous bullshit that it belied the very industry he worked in. He once said of reviewing movies, “Your intellect may be confused, but your emotions never lie to you.” I’m not ashamed to say that his reviews frequently made me cry. Too often film reviews rely on snappy snark to substitute for critical thought and clear writing, Ebert never had that problem.

In a seemingly increasingly cynical media landscape Ebert stood for the most passé ideals of all: humanity and humility. And we are better for it.

*

Sarah Nicole Prickett, Contributing Writer

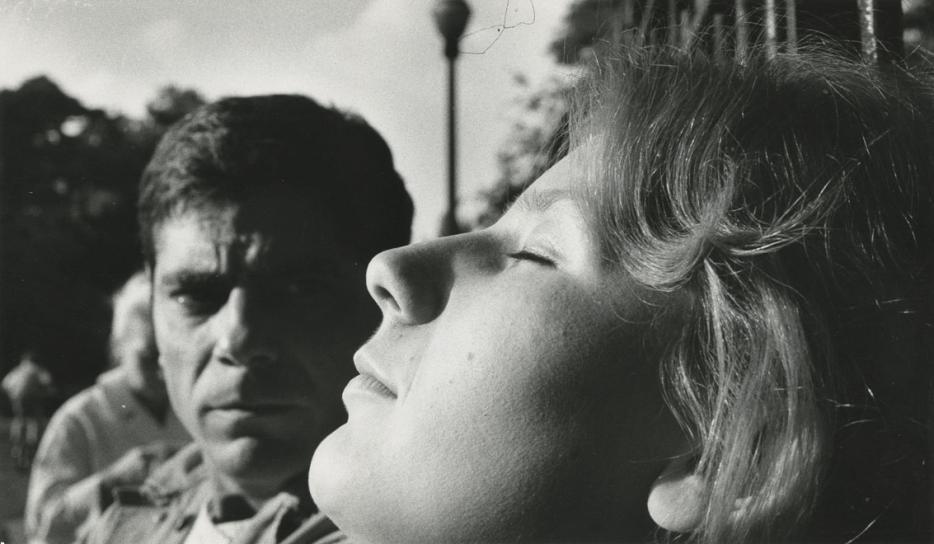

Monday night I wrote from two until nine a.m. and even then I didn't go to bed. I went to McNally Jackson. There are a few places in which I can usually feel certain, no matter how rattly my bones. McNally's like that. The previous Monday night I had stayed up not writing, but texting someone... how to describe? Someone I couldn't say I loved, even if I did. At eight a.m., drinking a coffee the size of my despair, I remembered it was Tuesday and I had to be in a photo shoot. I almost drowned myself. Then I remembered it was at McNally Jackson, and put on some jeans.

So Tuesday, this previous Tuesday, I walked into McNally looking for a photographer-girl I'd planned to meet. Instead I saw this guy. He stood up from his corner seat the second I looked into the café, stared right back. I froze. I felt rabbity, like he was someone who'd hurt me. But it was only that he had been in the same spot at the same time a week before, and that during the group shoot, I'd avoided the camera by sleepily eye-fucking him for an hour straight. He reminded me of the Spanish lifeguard I'd been in love with at 15. He had perfect teeth. I could tell. After the shoot I stayed long enough for him to say something, or vice versa, but when he picked up his skateboard (I mean...) and stood there, looking at me, I pretended I was replying to a very exigent text. If I saw him again it would be different.

It was different, this week—in that instead of being triply moisturized and made-up, I was coffee-veined and the colour of orange pith. Being one of the vainer people alive, I fled downstairs to the bathroom and put on lipstick. When I came back, he was gone. Well—I do like intelligence in a man.

Jowita Bydlowska, Contributing Writer

This week was heartbreaking. I spent two days at the National Job Fair in Toronto, working the booth for the non-profit employment magazine I write for. We were at the event to tell people about the magazine, but we don’t have any jobs to offer so I saw a lot of eyes cloud over once I’d pointed out this fact. The people who show up at the fair are unemployed—painstakingly dressed up, clutching folders with resumes, walking in uncomfortable shoes. They’re mostly newcomers, the newer ones still chirpy about being in Canada, but some already walking slower, heavier, sighing at us. And people like the guy who grabbed one of our brochures after tapping the table three times, then tapping three times before he grabbed the free pen. People used to get hired through these events, but the past few years there have been almost zero actual job openings—it’s mostly just booths and booths of pyramid schemes, college recruiters, someone trying to convince people to move to Saskatchewan, and then us, the non-profit agencies, trying to explain that we are the good guys (but that we have no jobs). This year was our last year exhibiting at the fair.

Coda: Week in Review appears every Sunday.