The 50th anniversary edition of Harriet the Spy, published earlier this year by Delacorte Press, comes with a blurb from novelist Jonathan Franzen. “I love the story of Harriet so much I feel as if I lived it,” he says. Franzen is an interesting choice for Louise Fitzhugh’s classic novel; true, he’s got no shortage of literary clout behind him, yet his brand of Time-approved Serious Grown Author seems at odds with a story about a precocious, rabble-rousing 11-year old girl. His name sends a clear message: sure, Harriet the Spy might be shelved in the children’s section, but it’s so much more than that.

Of course, many children’s books are way more substantial than they were originally given credit for (there is still a lot of fluff and crap published, but that’s true for any genre). This idea guides Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, a collaboration between children’s book specialists Betsy Bird, Julie Danielson, and Peter D. Sieruta. Wild Things is partially an argument for the legitimacy and impact of kid’s lit, but more than that, it’s a treasure trove of trivia, a collection of “Did You Know?” tidbits behind the iconic books of our youth.

Wild Things dedicates several pages to the legacy of Harriet the Spy and its author. Louise Fitzhugh was a champion of subversion. In 1961, pre-Harriet, she provided the illustrations for Sandra Scoppettone’s Suzuki Beane, a parody of Kay Thompson and Hilary Knight’s twinkly Eloise series. “This is our pad,” says Suzuki, introducing readers to the Greenwich Village home where she lives with her parents. “We all have a ball here. We don’t have much bread, but bread is really not very important when you have good relationships.”

Fitzhugh was also an out lesbian, which is the type of thing that doesn’t matter, except when it does—like when you’re the daughter of a Southern U.S. district attorney in the 1950s. Fitzhugh is rumoured to have eloped young to avoid being a debutante, and to avoid being caught in a scandal with another woman. She ended up in New York, where she wrote Harriet.

When I read a galley of Wild Things earlier this year, my recollections of Harriet the Spy were fuzzy. I hadn’t read Fitzhugh’s book in about 15 years. I remembered taking it with me on a camping trip, and I remembered it inspiring me to keep a notebook and give tomato sandwiches a try, but the gaps in my memory were filled in with the ’90s film adaptation starring Buffy’s little sister, Michelle Trachtenberg, and Rosie O’Donnell; a fine movie for a second grade slumber party, but one that, in retrospect, misses a lot of the book’s magic.

Harriet the Spy, the movie, is set in the time it was filmed, against the backdrop of what is clearly Toronto. Harriet the Spy, the novel, takes place on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in the early ’60s, a world of prestigious private schools and daily cocktail hours. The significance of this setting went over my head when I first read the book; for a kid, adults are more or less interchangeable, the gatekeepers of fun and freedom no matter where you live. Harriet first came to me as the plucky heroine of a fun story, but she endures as an icon of subversion.

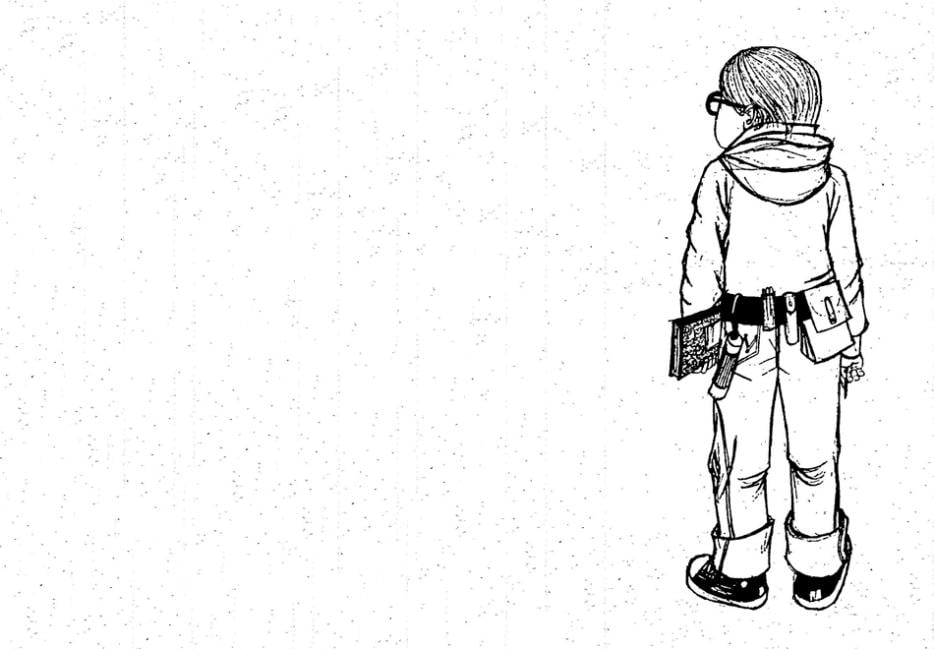

The most essential part of Harriet’s identity is that she’s a writer. She observes and takes notes, and tries to figure out who she is supposed to be by determining who she doesn’t want to be. She judges her classmates and sneaks into neighbours’ apartments after school. Being a spy means being inconspicuous, blending into one’s surroundings. An early chapter details Harriet’s spy outfit: old blue jeans normally forbidden by her mother, a utility belt, an old sweatshirt, scuffed-up blue sneakers (also forbidden by her mother), and “black rimmed spectacles with no glass in them,” pinched from her father’s study. It’s a uniform of function and practicality, and it’s also pretty butch: another detail lost in the ’90s adaptation, by which time girls in blue jeans were No Big Thing.

When Harriet’s parents propose sending her to dance class, she throws a fit and runs off to her room. Her nanny, Ole Golly (who doubles as her confidant), comes in to console her.

“Remember that movie we saw about the Mata Hari?” she asks Harriet. “Where did she operate?... She went to parties, right? And remember that scene with the general or whatever he was—she was dancing, right? Now how are you going to be a spy if you don’t know how to dance?”

Harriet considers this before responding, “Well, do I have to wear those silly dresses? Couldn’t I wear my spy clothes? They’re better to learn to dance in anyway. In school we wear our gym suits to learn to dance.”

“Of course not. Can you see Mata Hari in a gym suit? First of all, if you wear your spy clothes everyone knows you’re a spy, so what have you gained? No, you have to look like everyone else, then you’ll get by and no one will suspect you.”

Femininity is a disguise, a ruse: a tool that helps her blend in and observe, a means to becoming a successful spy and writer. With Harriet, Fitzhugh created an 11-year-old character who may still be years away from considering her sexuality but who understands the sacrifice of conformity. By the end of the book, Harriet more or less learns to play nice with her peers—by offering apologies to those that read her hurtful observations—yet her unfiltered scrutiny never stops. She just learns to be more careful about what she reveals. In an oft quoted passage, Ole Golly tells Harriet, “Sometimes you have to lie. But to yourself you must always tell the truth.”

The new version of Harriet the Spy, the one with the Franzen seal of approval, comes with a collection of essays, mostly by prominent children's book authors: Judy Blume, Lois Lowry, Meg Cabot. Many of the essays are variations on a theme: the writer in question read Harriet during their formative years and was inspired to keep a notebook. Harriet the character is important to writers, as they (we) will tell you again and again. But more than that, she's a symbol of how to make it through a repressed environment, if not unscathed then at least with a few stories to tell.