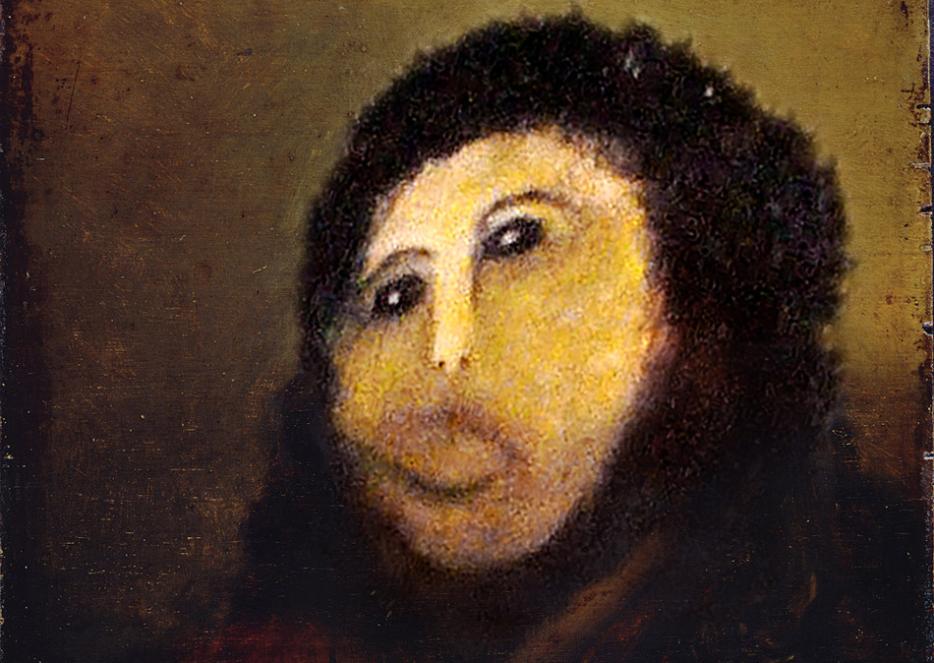

Sometimes, we can’t help but delight in other people’s misfortunes. From Rebecca Black’s “Friday” and Tommy Wiseau’s The Room to Cecilia Giménez’s well-intentioned but ultimately disastrous foray into religious art restoration, we as a culture are prone to LOL at spectacular failures. In his new ebook, Epic Fail, Mark O’Connell investigates the impulse to laugh at and deride the most earnest and flawed among us is good-humoured in its own right, and offers an examination of what it might mean to fail without comprehending our failures, including our own (epic) moral failure. Tracing a short history of the guilelessly untalented, from novelist Amanda McKittrick Ros—who left Aldous Huxley, among others, in stitches from the literally incredible and comical badness of her prose—straight on down to the famed Monkey Jesus Fresco Fiasco, O’Connell paints a subtle picture of epic human hubris, cruelty, and, yes, failure.

One of the things that struck me from the examples of epic failure you described in your book was how the more contemporary ones were, I suppose, “appreciated” through social media, such as the forum discussion and YouTube comments about Rebecca Black and Tommy Wiseau. I was thinking about how democratic that sort of ironic enjoyment seems, in comparison to Amanda McKittrick Ros, who was appreciated, it would seem, however ironically, mostly by professionals—other writers and critics.

Yeah, right, that’s an interesting point. The whole culture of the epic fail has become much less masonic. It’s now much less an “insider” thing, but I think I say in the book it’s still like an inside joke, but—paradoxically—an inside joke that the whole world is in on. I’m old enough to remember actual VHS tapes being passed around from hand to hand, so even in my lifetime, this kind of thing was much less “democratic” and much more of a masonic thing. Is the phrase “democratic” quite applicable here, though? I don’t know. It strikes me now that it’s not something I really explored that much in the book.

Although isn’t, say, Tommy Wiseau still something of an inside thing? I sort of thought he was almost an Internet household name until the book came out, and quite a lot of people told me that they’d never come across him before. And, bizarrely, I had someone in their 20s who works in publishing tell me that they’d never come across Rebecca Black before, which I found really hard to credit. But there you go. I think, if you’re on Twitter or whatever, you can get a slightly skewed sense of how big an impact this stuff has.

Absolutely. That skewering of the way we understand what art is, bad art included, by the Internet is interesting. How “epic” does a failure have to be to qualify nowadays for the kind of mass ironic appeal we’re talking about? (I also am amazed a person with access to the internet could be unfamiliar with Rebecca Black.)

I know, seems amazing. Although I’d quite like to be exposed to less of this stuff myself. But yes, I talk quite a bit in the ebook about how important context is to this stuff. Like with the Cecilia Gimenez thing, I think what the whole world—or the part of it that we’re concerned with here—was really provoked by was not just the crappy Jesus fresco itself; it was the reality of the elderly lady behind it, her complete comic haplessness and so on. The personal element is really important.

Or with The Room, so much of the fascination there with Tommy Wiseau, as a guy, as opposed to just the movie. Which by the way, I watched for the first time when I was writing the book, and found just intensely boring. I could barely make it through the film. But Wiseau himself I found completely compelling.

Another example that I didn’t discuss in the book was that Olive Garden review by that old lady newspaper columnist. Did you see that at the time? That whole thing seemed to be all about the writer as opposed to the text.

Which leads me to my next question: Is Guy Fieri, the man or his flavourtown empire, a contender for epic, ironic, failure?

He’s just awful, isn’t he? That’s not a judgement so much as I’m asking a genuine question. We don’t get too much Fieri-based content over here [in Ireland], so I’m hearing it all second-hand. Steve Albini, of all people, had a very long and funny rant about him on his blog a while back.

Did you see the incredibly snarky review of his Times Square restaurant?

Oh yeah, I did, that was brutal. But I don’t know if Fieri can be considered an echt epic failure; he’s massively successful because people enjoy him unironically. He’s successful despite all the people who think he’s the worst thing ever, right? Unless—wait—are people in North America eating hamburgers ironically now? I don’t know if it’s possible to make a really solid living out of people liking what you do ironically. Although surely there’s an example of that somewhere.

What about Tommy Wiseau?

I think Tommy Wiseau made his money out of importing fake leather jackets from Korea.

But I do wonder, as you did (along with a faction of the Internet’s Greek chorus) about his awareness of being mocked, and I’ve often wondered the same thing about Guy Fieri.

Yeah. It’s really difficult to tell. My hunch is that, with a certain type of person, the complete lack of self-awareness that makes them so mockable in the first place also protects them from really understanding the extent to which they are the subject of mockery. If you’re convinced of your own greatness, you’re not going to be particularly bothered by people throwing peanuts from the cheap seats. Even if your whole career is people throwing peanuts from the cheap seats.

Actually, I know almost nothing about Guy Fieri, apart from that he’s got frosted tips and people hate him. (I just Google image searched him there—he’s frosted all the way, not just tips.)

My favourite part of your book is when you riff on how these epic failures destabilize the very forms they fail in—how, after watching Wiseau perform, it clarifies the general artificiality of performance. Do you think the sense of that uncanniness is a major part of the attraction? If writers and critics valued this uncanniness in Ros, is that an unwitting part of the experience for the average commenter on “Friday,” who presumably has been as exposed to pop music as say, Huxley was to literature?

Wow, I don’t know. I started to think about that specifically in relation to Amanda McKittrick Ros, and I think part of the reason for that was that—purely as a result of the nature of reading a novel—I’d spent so much time with her. So reading so much of it had this weird effect whereby her badness seemed to affect my experience with any kind of literary writing at all. As a kind of experiment, I read some Marilynne Robinson and some John Banville shortly after reading Ros (these are, for me, two of the greatest writers of sentences in contemporary literature), and I found that I almost couldn’t take them seriously.

But I don’t know how much the Amanda McKittrick Ros cult would have valued or recognized this aspect of her work. I mean, you might read her and have a completely different reaction. It could be just an idiosyncratic thing with me. I’d be surprised if that was a major element of the reaction to Rebecca Black. I certainly didn’t see any evidence of it in the YouTube comments.

I think I meant it more as an intuited reaction, not necessarily the one we first notice in ourselves, but present all the same. (You compare the experience of listening to Rebecca Black’s musical stylings to the notion of the Uncanny Valley, and I think I may have just ran away with it.)

Yeah, it’s definitely in there. I mean something all these works of art have in common is, in a weird and counterintuitive sense, a certain closeness to competence—a kind of uncanny closeness to competence. Definitely with Rebecca Black. I mean, I can still hear that song and think it’s not that bad. I don’t really see it as being that much worse than stuff people listen to unironically.

Me too! I actually like that song.

It’s a perfectly serviceable pop song, no question. It’s got a nice beat to it, as your dad might say. And when you consider how quickly it was written and recorded? Cut ’em some slack.