A couple of weeks ago, one of my favourite customers e-mailed asking about my thoughts on digital culture and books. I’m considered a bit of an easy touch when it comes to this sort of thing because I’m old, irritable, and generally indisposed to many facets of said evolving digital culture, but most especially when it comes to books.

I forgive you if you immediately dismiss my opinions because my horse, is, of course, as a bookseller, firmly tied to the wagon of the traditional printed book. But I think there’s much more at stake here than my continued prospects of gainful (a term I use advisedly) employment.

Naturally, I’m reminded of two books.

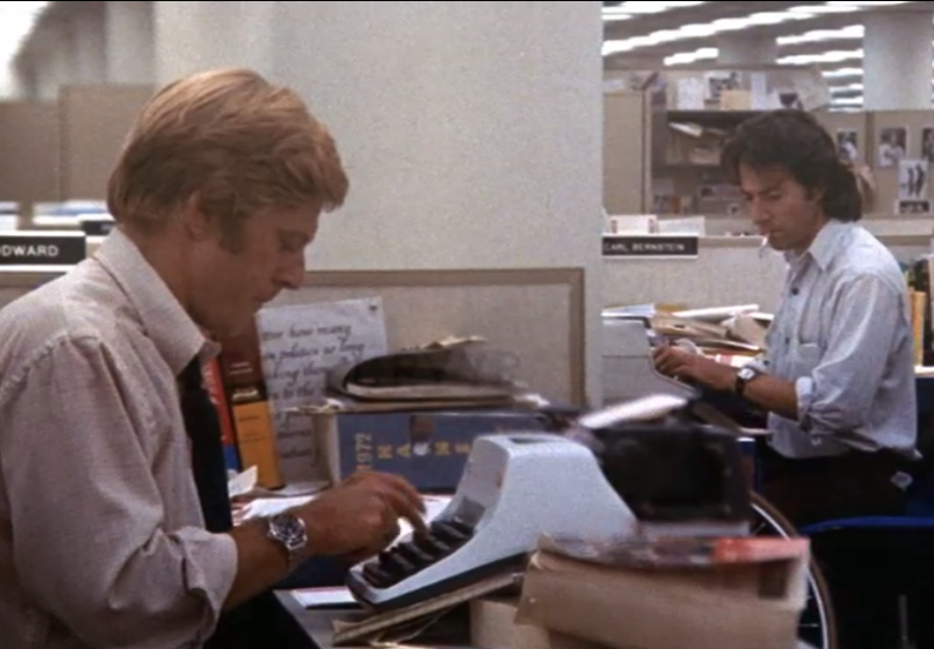

In his recently published and phenomenally successful volume about the remarkably interlocked worlds of politicians and pundits in Washington, D.C., during the last five years, This Town, New York Times Magazine correspondent Mark Leibovich, eventually gets around to a very brief consideration of Watergate.

The break-ins at the Watergate complex, which eventually brought down the presidency of Richard Nixon, showed the potential power of an independent press.

Leibovich asks whether the story could have been broken today, or if it would have been able to remain a story long enough to have any effect.

“A complicated story would devolve into the familiar left-right rock ‘em, sock ‘em. … Soon enough Watergate would be over, eclipsed by the next shiny object…” A comforting prospect, surely, for anyone who thinks that crimes committed by governments are best dismissed as shiny objects, bijoux for those with short attention spans.

The second book that came to mind was Ted Mooney’s woefully underappreciated 2010 novel The Same River Twice. In Mooney’s story, a filmmaker discovers, only by a complete fluke, that one of his earlier films has been changed, and that there are copies in circulation in which the ending has been altered. He is unable to discover who would have perpetrated this incomprehensible offense, why they might have even considered it, or how many copies of it there are in existence.

With those cases in mind, it seems to me that among the almost innumerable (and seemingly intractably complex) issues involved in the discussion of books and the Information Age, two are particularly noteworthy.

The first is that only small and gradual changes are required to completely obscure the original meaning of a work of art or scholarship. In the torrent of information that flows into the collective consciousness daily, it would take a long time before anyone noticed those changes—and by the time people did notice, they might be impossible to correct. Wikipedia, for example, may have a diligent community of editors, but a reader who happens upon a piece misinformation, deliberate or not, ahead of its correction may not be searching subsequently for secondary confirmation; indeed, that reader may not even realize they’ve been deceived.

The second issue, and perhaps the more troubling one, is that there are entities for which obscuring the original meaning and intent of those works is advantageous—an act that is now, in many ways, easier than ever.

If there are people who think that there is merit in allowing either a government or a corporation to be the ultimate repository of all published work, clearly that’s a problem much greater than my own dinky little bookstore. If we’ve come to the point where most people think that, or worse, can’t be bothered to care one way or another about it, then the subject of books themselves might be the least of our worries.

Ben McNally has been a bookseller, and tireless promoter of books and authors in Toronto for more than thirty years.