Few film directors seem as directly present in their work as Werner Herzog. Not only does he have an instantly-recognizable aesthetic, but unlike most European auteurs of his generation, he has become a familiar face in front of the camera. We are so accustomed to seeing him—playing football with Peruvian indians, arguing with Klaus Kinski, eating his own shoe at Chez Panisse—that we might mistake him for just another "personality," one of the celebrities who parade past at various scales, from cellphone to Times Square, on our screens. Directors are required to be showmen, particularly directors of documentaries, who always have to hustle to finance and screen their work. But Herzog’s presence, his insistence on being in the middle of things, is something more like an artistic strategy—which is to say it’s the very opposite of a strategy, unless it’s possible to be both strategic and uncalculated, canny and impulsive at the same time.

August 23, 2012

In Cave of Forgotten Dreams, his 2010 documentary, Herzog can hardly help appearing on screen. The Chauvet cave, sealed off for twenty thousand years in a limestone cliff above the river Ardèche in the south of France, was rediscovered in 1994. It was found to contain hundreds of paleolithic paintings of horses, mammoths, cave bears, bison, lions, and other animals, which may be over thirty thousand years old, almost twice the age of previous finds. The caves are being studied by a team of scientists and access is extremely restricted. Herzog and his crew had to shoot the whole film from a two-foot wide metal walkway running along the cave’s floor, using hand-held lights and a stripped-down camera. They frequently appear in shot, having nowhere to hide. In voice-over, Herzog speculates about the origins of art, about being "locked in history," and the impossibility of bridging the distance that separates his image-making from that of the painters, working in charcoal and red ochre on the cave walls. Hearing his familiar voice musing about these familiarly Herzogian themes has become weirdly comforting. It’s hard to remember how confrontational and strange his essayistic personal style seemed when audiences first encountered it.

Herzog’s first appearance in one of his own films comes in a 1974 German TV documentary. In The Great Ecstasy of The Woodcarver Steiner (Die Grosse Exstase des Bidschnitzers Steiner), his subject is a champion ski-jumper, a man who is pushing back the frontiers of his sport. We see footage of Walter Steiner, a phlegmatic young Swiss man with a long nose, jumping 179 meters, landing badly. “We’re approaching the limit,” he explains. “Maybe I’d prefer to turn back…” Cut to Herzog, glowering darkly beside a ski slope. He taps a wooden stake that marks Steiner’s record-breaking jump. “This is the point where ski-flying becomes inhuman.” Had Steiner jumped a few meters further, he would have landed on the flat, the equivalent of falling from a 110m high building. Herzog explains that his film "had its inception" at this marker. The word he uses in German is Grenze, a border.

At the world championship in Yugoslavia, Steiner effortlessly outclasses the competition, but his mood is anxious. He is exceeding the parameters of the course, which puts him in terrible danger, yet the organizers will not listen. Again, he makes a jump that exceeds the previous world record, but falls. Herzog is at the top of the slope, communicating with his cameraman through a walkie-talkie. He believes Steiner may be badly injured. But after cursory treatment, we watch Steiner walk unsteadily out of the medical tent, the side of his head smeared in iodine. Twenty minutes later he jumps again.

When Steiner jumps he is shown in slow motion, accompanied by the plangent minimal music of Florian Fricke’s Popol Vuh. His mouth hangs open in an "o" of terror and wonder. When he is in mid-air he literalizes, again and again, what for most people is just a vague metaphor: ecstasy. Ek-stasis. Standing outside the body, reaching out towards the infinite. Steiner is trying to jump as far as he can, but if he jumps too far he will die. He has come precisely to the border between life and death. Herzog watches him fly, a fan who has succeeded in capturing the sublimity of Steiner’s experience with great simplicity and beauty.

Herzog did not appear on camera by choice in The Great Ecstasy of the Woodcarver Steiner. The film was made for a German television series called Border Stations (Grenzstationen) and the format demanded that he appear on screen. Later he was to grow confident, not only acting as the narrator of his films, but appearing as a physical presence, coaxing, scolding, wheedling the filmed story out of raw unstructured life. Herzog always seems to be on the verge of participation, of undergoing the story he is trying to tell. His "documentary" films (which usually have an element of fiction, just as his fictions often have the look and feel of documentary) sometimes seem like elaborate mechanisms to allow the director to experience the trials and joys of his subjects, whether they are stumbling starving through the Laotian jungle (Little Dieter Needs to Fly), or crawling across the ice in religious supplication (Bells from the Deep). Of course, when it is possible to participate directly, he does so. He flies in an airship through the cloud canopy of the Guyanese rainforest (White Diamond). In La Soufrière, a film whose German title (Warten auf eine unausweichliche Katastrophe) translates as "waiting for an inevitable catastrophe," he climbs a volcano as it is about to erupt. The catastrophe is always imminent in Herzog’s films. It is the shadow in which he positions himself for his piece to camera, a lugubrious moustachioed Orpheus, reporting live from the Underworld.

His 2005 film Grizzly Man was assembled from archival footage left by bear enthusiast Timothy Treadwell after he and his girlfriend Amie Huguenard were killed and partially eaten in 2003. Treadwell spent thirteen summers in an Alaskan national park, living close to bears, against the advice of rangers who warned him it was unsafe. Treadwell’s video camera recorded audio of the fatal attack. Jewel Palovak, Treadwell’s ex-girlfriend and business partner, gave Herzog permission to listen to this "border crossing." We see the director hunched over, wearing a pair of headphones, as Palovak sits with the camera in her lap, scrutinising his reaction. He begins to describe what he is hearing. Then he falls silent. The shot gradually tightens to a close up of Jewel’s stunned face. She has never played the tape herself. Finally Herzog asks her to turn the camera off. “Jewel, you must never listen to this,” he says. “And you must never look at the photos I have seen at the coroner’s office.” She promises not to. And of course we, the audience, will not hear or see these things. Herzog has been to the other side on our behalf.

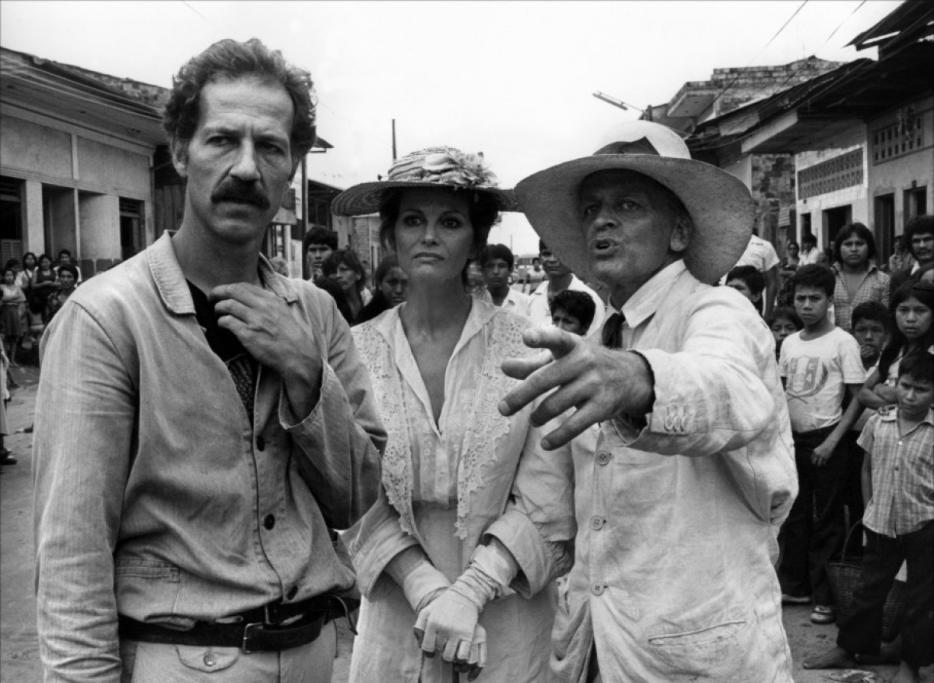

Herzog’s feature films often seem the byproduct of some transformative, often traumatic experience undergone by the director and his crew. Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo, the two films he made in South America with the monstrous Klaus Kinski, have become legendary for their production problems and the confrontations between director and star. In Fitzcarraldo, which deals with a nineteenth-century rubber baron who dreams of building an opera house in Iquitos, Herzog famously insisted that the film’s central image—moving a 300 tonne steamship over a hill—be achieved without special effects. He also filmed on board the ship as it careened through a set of rapids. Both productions were shot in inaccessible locations, and the crew underwent great hardships. Les Blank’s 1982 documentary, Burden of Dreams, shows a Herzog who seems devoted to capturing the image as if it were a wild animal, stalking it, lying in wait.

On the set of Rescue Dawn, Herzog’s ill-fated foray into Hollywood, the director alienated his mainly American crew by his insistence on being at the center of the action. His lack of concern with continuity or coverage and his use of hand-held shots, instead of the elaborate set-ups and special effects expected on an action movie, led to a state of war between Herzog and his inexperienced producers. The crew were secretly ordered to film additional footage and sneak it into the rushes. After Herzog insisted on wading into a fast flowing river to get a shot, his cinematographer told a journalist that “we have a camera that’s protected inside a Lucite box, which allows you to place it right in the water. He could get the shot without any physical contact. But that’s not what he wants. He wants an adventure.”

Herzog’s wish to be present in his films, to experience what he is trying to understand, can seem avaricious. Critics who feel uncomfortable with some of the situations (and people) he puts on screen frequently question his ethics. Yet his avidity for extreme experience has nothing cold or cynical about it. He seems one part ethnographic participant-observer to one part strikingly old-school German Romantic, an artist who considers his work no more than the trace of the experience that produced it. The various Herzogian heroes—in fiction, documentary, and his various blurrings of the two—are all avatars of a Romantic subjectivity: the megalomaniac Kinski, the abused but powerfully-dignified Bruno S, the murderous madrigal composer Gesualdo, Dieter Dengler who wants to fly but is shot down, revolutionary dwarves, child soldiers, hypnotized villagers… None are more powerful than the ski-jumper Walter Steiner, to whom Herzog gives an epigram, adapted from the Swiss writer Robert Walser. “I should be all alone in this world. Me, Steiner and no other living being. No sun, no culture: I naked on a high cliff, no storm, no snow, no streets, no banks, no money. No time and no breath.Then I would no longer have to be afraid.”

Steiner’s words are a description of life-in-Death, perfected, changeless and absolute. But Herzog knows that to be alive is always to be somewhere rather than nowhere, which is why his films are always concerned with landscape. Like WG Sebald, Iain Sinclair, Richard Long, or his friend Bruce Chatwin, Herzog is an artist who understands the world by walking. In 1974, when he heard the German film theorist Lotte Eisner was dying in Paris, he set off on foot from Munich, "in full faith, believing that she would stay alive if I came on foot." She did.

Herzog is one of cinema’s great photographers of the natural world. In Herz Aus Glas (Heart of Glass), his story of a mythical cowherd prophet and a cursed village of glassblowers, opens with a short visual essay on the country in which he grew up, the Chiemgau Alps of southern Bavaria. In a shot he has described as one of the best of his career, a river of cloud flows like water across a vista of forested mountains. It took eleven days to capture, exposing single 35mm frames by hand-clicking the shutter. Then the cloud becomes mist. The mist becomes a waterfall, shot so it is just an abstraction of falling, a constant plunging of matter into the abyss.

Herz aus Glas presents a metaphysical German terrain of forest clearings, cliffs, and bridges over deep chasms. As in all of Herzog’s films, a constant aesthetic presence is the painter Caspar David Friedrich, for whom landscape was a frame for the infinite void. Herzog famously didn’t see television or make a phonecall until he was in his late teens, and his identification with the figure of the Naturkind, the child of nature, is profound. But Herzog, the village boy, became a great traveller. His films are studded with extraordinary locations from all over the world, which are often abstracted from time and culture to stand for metaphysical states, or as contextless "science fiction" settings for Herzog’s fabular fictions. Even Herz Aus Glas, as echt Bavarian as it is, contains images shot everywhere from Yellowstone National Park to the Skellig islands.

Of course, for a German film director, the landscape is not innocent. Under Joseph Goebbels, Nazi aestheticians hollowed out the traditions of German Romanticism and used them for their own ends. In Nazi-era cinema, the Mountain movie was a favorite genre, complete with heroic figures imposing their will on Nature, while being infused with its mystical energy. Sachrang, where Herzog grew up, is a few miles away from Berchtesgaden and the Berghof, Hitler’s mountain residence. After the war. In the traumatized postwar Germany of Herzog’s youth, German cinema had retreated into insipid Heimatfilme, sentimental depictions of rural life, that were less repudations of what had gone before than distasteful echoes of it.

Thus when Herzog opens Jeder für Sich und Gott Gegen Alle (“Every man for himself and God against all,” blandly known in English as The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser) with the paradigmatically Nazi image of a field of waving corn, it is a deliberate provocation. Herzog was one of the first film-makers to dare to re-imagine Romantic landscape (another was Wim Wenders), to wrest it free of trashy sentiment and Fascist yearnings for domination, to dare to think again about a man standing alone on a high cliff. The postwar generation, who took up arms against what Gudrun Ensslin of the Red Army Faction called "the generation of Auschwitz," were very attracted to the transcendental, but rightly suspicious of its organization in the service of Power. In the 1970’s, Herzog’s krautrock-soundtracked under-dog Romanticism, though never commercially popular, caught a note of authentic yearning, the wish for what Herzog has termed "ecstatic truth."

From Fata Morgana, his essay on "demented colonialism" and the Sahara desert, to the calcified womb of the Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Herzog has made it his mission to re-spiritualize landscape, to allow fear, awe, and wonder to reinhabit our perception of the natural world. But, however grounded he is in the canonical images and themes of the German Romantic tradition, he is not content to reproduce conventional images of the Sublime. The oddest, most authentically Herzogian note in Cave of Forgotten Dreams comes at the end, where the camera drifts away from Chauvet and the cave paintings to a nearby tropical biosphere, where it picks up an extraordinary image of two albino alligators mirroring each other as they float in the water. Its connection to the ostensible business of the film is tenuous, but it is authentically fascinating, and in the end that is Herzog’s only binding aesthetic criterion for putting something on screen.

In 2010, Herzog published the text of a speech he gave after a screening of Lessons of Darkness, which overlays a science fiction premise onto hallucinatory images of the devastation wrought on Kuwait by the Gulf War. In it he expounds on the difference between truth and fact. It is a statement which gets to the heart of why his documentaries feel like fiction, why his films include albino alligators, and why he is always chest-deep in the river, rather than looking at a monitor on the bank. “We must ask of reality: how important is it, really? And: how important, really, is the Factual? Of course, we can’t disregard the factual; it has normative power. But it can never give us the kind of illumination, the ecstatic flash, from which Truth emerges.”

--

This article originally appeared on Hari Kunzru's blog.