The audience, it was widely reported, gasped in collective disbelief. The appearance of Salman Rushdie on the Winter Garden Theatre stage in Toronto on December 7, 1992, startled the thousand audience members who had come out to the annual PEN Canada benefit expecting to see many writers, but not the author of The Satanic Verses, then in his third year of living with a “sentence of death,” courtesy of Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini. His electrifying presence in the theatre was less of a surprise to Margaret Atwood, who had elicited that gasp by introducing him. For organizers Louise Dennys, then the president of PEN Canada, and Marian Botsford Fraser, chair of the benefit, the visit had been the result of four months of intensive preparation, all done in secrecy, and with much worry and stress. Told that his trip to Canada could be cancelled without warning, Botsford Fraser had been obliged to prepare two programs for the night, just in case.

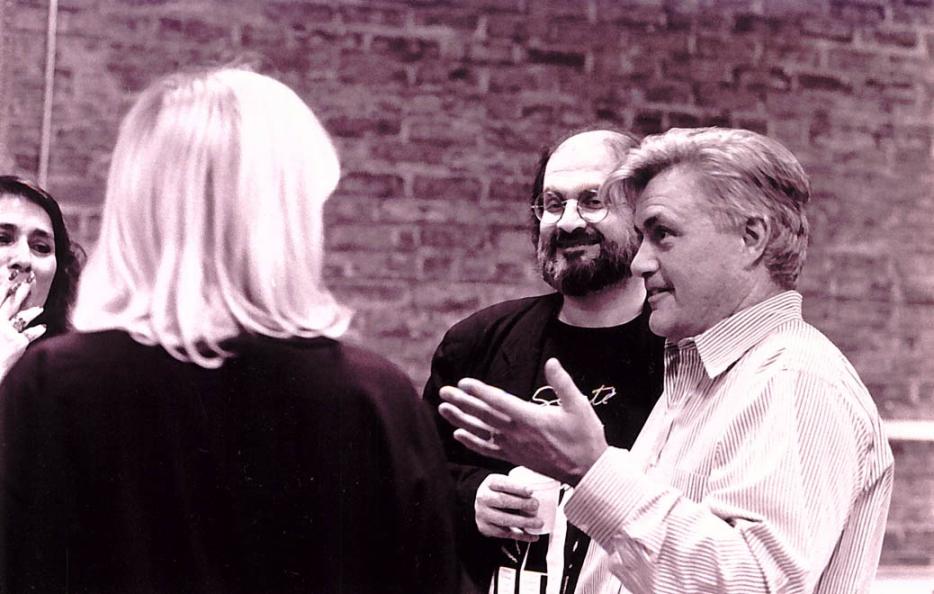

But there he was, attired in a suit jacket over a PEN t-shirt reading The Sentence for Silence—Help! Free Writers, and grinning at the podium while the thousand roared in delight and spontaneous support. “Then the ‘Rushdie’ part of the program began,” Salman Rushdie would later recall in his memoir Joseph Anton, “and it felt like the highest of literary honours...” One by one, some of Canada’s finest writers joined him on stage to outline the chronology of the fatwa. John Irving, an old friend, read passages from Midnight’s Children before Rushdie himself said a few words about witches—“Anybody’s a witch if you point at them and say they are”—and how he found it “touching and sustaining and nourishing” that so many people had sent letters sharing their dreams of saving him from the “mad Imam in Tehran.”

Next, he read a short story—Dennys, his Canadian publisher, had wanted him to simply be a writer among writers for a few minutes—before the PEN president read a letter of support from Canada’s secretary of state for external affairs, Barbara McDougall. Dennys then earned another, albeit lesser expression of shock from the audience by announcing that the premier of Ontario, Bob Rae, wished to speak as well. By so doing, Rae became the first head of a government anywhere in the world willing to be seen in public with Rushdie since the bounty had been put on his head. The premier called on governments to “do the right thing.”

The day before the benefit, PEN Canada’s secret guest had stayed with Michael Ondaatje and Linda Spalding, been interviewed on the CBC by Peter Gzowski, and had dinner at the home of Adrienne Clarkson and John Ralston Saul. Like the audience at the Winter Garden Theatre, Canadian writers had embraced the embattled novelist. But as Dennys later reported, the real purpose of his visit had been to win Canadian government support for both pressuring Iran to rescind the death decree, and bringing its government before the International Court of Justice. Rushdie himself, having remained quiescent and largely hidden away for security reasons during the first two years of the fatwa, had lately resolved to be more pro-active about his case, and his fate. “I want to make some noise,” he would shortly tell the New York Times. Given the lack of support so far of national governments and heads of state, much of it tinged by realpolitik and pressures from business concerns—a roll call of dis-honour outlined in Joseph Anton—PEN might have worried it would fare little better making noise in Ottawa. “There’s no reason for any special relationship with Rushdie,” White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater had informed reporters of an earlier visit by the author to the United States. Washington had not welcomed him then.

What happened in Ottawa on December 8 proved a pleasing contrast. First, Dennys and Rushdie met with Barbara McDougall in her office, where the minister offered the full support of the Conservative government. Security forces then escorted them to the offices of first the leader of the NDP, Audrey McLaughlin, and then that of Jean Chretien, the leader of the official opposition, where they chatted with a group of Liberals MPs. Chretien had to end the meeting to attend the House of Commons, where he immediately asked Prime Minister Mulroney why he wouldn’t shake hands with Salman Rushdie. (The PM was grilled over his decision to leave the face-to-face to McDougall for several days.) Later that day, Rushdie sat before a parliamentary Sub-Committee, where his testimony was pivotal to Canada passing unanimously an all-party resolution urging that the fatwa be rescinded, and the bounty withdrawn.

As Joseph Anton makes clear, Rushdie’s struggle not to be silenced, to assert under extreme duress the principles of free speech and artistic liberty, went on for another almost seven years. Initiated during the epochal year of 1989, when much of global communism collapsed, triggering the globalized, free market 1990s, the fatwa would only wind down at the close of that decade, within sight of the shocking onset of the era it so eerily pre-figured—the planet post-9/11. His stop in Canada in 1992 was one of dozens of similar efforts on his part, and that of his many supporters.

But for Canadians, the three days of his visit were quietly significant for reasons that have only became apparent in those subsequent decades. The Toronto-based PEN Canada, formed only in 1983, came of age that December, demonstrating both the influence of its constituency and the force of its commitments. (It is easy to forget how palpably afraid people were that Salman Rushdie would be assassinated in public. Never mind his own very real fears for his life; everyone from airline passengers to heads-of-state were scared of even being near him.) By how it handled Rushdie’s visit, PEN Canada showed itself to be both an effective advocate for freedom of speech, and simply willing to walk the walk of its beliefs. Likely it is no coincidence that in 2012 the president of PEN International is the same John Ralston Saul, while the chair of the international Writers-in-Prison committee is Marian Botsford Fraser. Margaret Atwood is a vice-president of the organization, and Toronto journalist and author Haroon Siddiqui sits on the board.

“Anybody’s a witch if you point at them and say they are.”

Interestingly, 1992 also saw a Canadian writer finally be awarded the Booker prize. Salman Rushdie’s host in Toronto, Michael Ondaatje, was then newly crowned for The English Patient. (Ondaatje shared the prize with Barry Unsworth.) Atwood, already thrice short-listed, would win in 2000 for The Blind Assassin and Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, one of the biggest literary novels of the new century, was awarded the 2002 Man-Booker. Yann Martel, as it happens, serves on the advisory board of PEN Canada while his father, Emile Martel, is president of PEN Quebec. Good writing, plus commitment and engagement, seems the national literary model.

No question, how Salman Rushdie was received first by Bob Rae, on behalf of the government of Ontario, and then by politicians and officials in Ottawa elevated his visit to a high point in Canadian public life. Brian Mulroney may not have met him, but his government was welcoming, and then acted supportively on both his behalf, and that of the larger principle. In 1992, Canada, and its federal governments, had a reputation around the world for decent, generally progressive principles and policies, and not only in the realm of free expression and human rights. But those days, and that reputation, now feel distant.

In retrospect, the other lingering disappointment about the aftermath of December 7, 1992 has been the limited success to date in re-introducing The Satanic Verses as an essential 20th century novel, rather than the book that caused such upset. Before the Ayatollah Khomeini took cynical umbrage, Salman Rushdie’s funny, roaring, phantasmagorical fourth novel was being celebrated for what it was, and still is: a benchmark of literature about the globalized identity, and a dialogue aimed at crisscrossing continents, races, and even religions.

“For a time I used to get really upset about the fact that this book had been attacked by people who had not read it,” Rushdie admitted to the audience at the Winter Garden Theatre. But then he figured the problem out. “Perhaps it’s not very easy to burn a book once you’ve read it.” Twenty years ago, with all the furor and distortion surrounding novel and author equally, there were reasons why even people who didn’t attack The Satanic Verses couldn’t easily read it as a work of literature. Now there are no reasons. Now the book awaits.