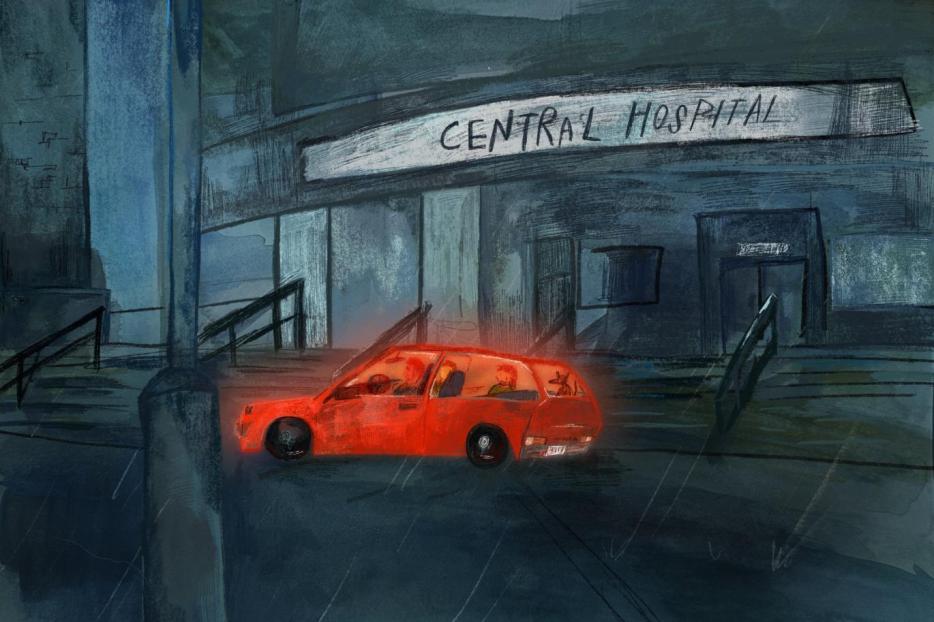

I’m 16 and Arthur is sitting in his red Honda, parked outside my school.

The windows barely contain his full-volume Verdi. As soon as I step outside, the lilt of his muffled underwater opera alerts me to his whereabouts. He’s lost in his leather aria, grinning, his wild grey curls alert, electrified by the music.

“Get in!” he laughs, flinging the passenger door open. “I told your mother we’d meet her at the park with Thai food!”

I smirk with the affected skepticism of every teenage girl in a kilt. Secretly, I feel safe.

He pops by on an unremarkable Sunday with a pot of clambering ivy for our empty kitchen windowsill. Hours later, he and my mum are on their second pot of Earl Grey, sitting at our vintage cream-coloured dining table and vigorously debating the modernized production of La Bohème they saw last week. Is it ill-advised to put a contemporary spin on a classic love story? How much risk is too much risk?

My dad left us a year ago and our new house is filled with boxes and promise. My mum has an explosively successful career as a neuroscientist. But after my sister and I have fallen asleep, she closes her bedroom door with a slow and certain click and examines the quiet wounds that linger from her marriage. She looks at me and my sister each morning with a burning, unwavering focus while impressed and curious men in their fifties mill about in the distance, shuffling around in burgundy sports jackets with their hands in their pockets. She appears to neither need nor want a romantic relationship, which only makes more of them gather.

Arthur and my mum share mystery novels and classical music and the kind of endless, expressive conversation that confused and exhausted my quiet, stoic, old-school European dad. Her final attempts to engage him the way she longed to be engaged only made him recoil and retreat further into an unchecked clinical depression. And then he was somewhere we couldn’t call him back from, and his silence shattered the walls.

But this house is flooded with spontaneous snort-laughs; warm, butter-yellow linen curtains flung open on hopeful August mornings; stacks of homemade CDs with Arthur’s eager, all-caps longhand marching down their tiny spines. He marvels at pewter salad bowls, declares the meal we’re eating miraculous. He helps us rescue the particles of light that had slowly sunk to the bottom of our old house under the roiling waves of my dad.

Arthur is seemingly riveted by every breathless half-thought my sister and I have about overnight camp and the dizzying backstage dramas of our weird school play. He stays firmly in the room for moral support when I’m failing calculus, mumbling at my mum that math is often improperly taught.

Arthur isn’t just a dad to us. He has two kids of his own with his wife, Wendy, a sweet and reserved woman with a long, tired braid parked on her back like an abandoned train. Sometimes he and Wendy have a fundraiser to go to, or a thing at the kids’ elementary school. They’re talking about getting a dog, but it would have to be one of those hypoallergenic ones.

Is it okay that he’s over here so often, hooking up my mum’s speakers and swirling his single malt Scotch, smiling as she tells him a work story that requires so much theatrical hand gesturing that she absently hands him back the glass he just handed her so she can do the performance justice? We all wonder privately, looking out car windows. He drops me off at dance class. He picks me up.

Their relationship is a maddening Rorschach test, a prism, a curious shape-shifting thing. Are they or aren’t they? I’m constantly tilting it so it catches the light. Just when I think I see it properly, the light changes and the colours change with it. It’s an extraordinary friendship, I decide. There. I’ve named it. Organic, inevitable, spilling over in the sunlight like the sprawling ivy in our window.

But sometimes, when Arthur mentions his wife, I hear my mum hastily paper over her discomfort. She works hard at offering an open, airy interest, but she’s fidgeting with the tag on her tea bag, lost in a strange and tiny origami—pausing, trying then to undo it, smooth it out, go back and un-complicate the suddenly complicated thing. I envision Wendy waiting at their dining room table while her husband becomes more and more of a fixture at ours, as expected and assumed as the low-hanging glass chandelier that smacks our heads when we’re putting out the soup bowls. She’s an uncomfortable, quiet presence in my periphery, a sudden gasp when I’m finally beating Arthur at Scrabble: Wait, doesn’t he belong to us?

Arthur and my mum never touch. I’ve never even seen them hug. Arthur goes home dutifully again and again. My sister and I linger by the coat closet and tease our mum after he leaves. Our young hearts want simple stories. She rolls her eyes, smiling just a moment too soon as she heads upstairs to bed.

* * *

A year later, it’s the kind of Sunday that has the feel of Arthur’s imminent arrival.

He doesn’t come.

My mum busies herself with warm croissants and the waiting crossword. The soft, rolling hills of Verdi’s Requiem are muted behind her closed bedroom door. Downstairs, the afternoon stretches out and yawns, silent but secretly hopeful. He never shows up.

A month groans and creaks under the accumulated weight of his absences. I’m 18 now, about to start university. I’m placing my books in boxes when my mum appears in my door frame.

“Where’s, like, Arthur?” I ask.

“Oh, you know!” she says brightly, spritzing an excessive amount of Windex onto my empty shelves. “He’s around.”

It will be more than a decade before I see them together again.

Whenever my sister and I are home from university, we’ll all lie in my mum’s king-sized bed and watch old Jack Lemmon movies, talking long after the DVD player’s neon green screensaver blob starts bouncing rhythmically off the corners of the television screen, a silent metronome for our conversation.

As my sister and I tumble through our own absurd couplings and crushing breakups, as we try to make sense of messy and uncomfortable love, that conversation occasionally meanders back to Arthur. My mum still looks at us with the same unwavering focus, but we’re peers now; we’re women. One night she’s still for a moment—contemplating, deciding. Then she reaches back into our childhood to tell us the story we were always clamouring for her to tell.

“I just couldn’t do that to his family,” she sighs. “It would’ve been wrong.”

I’m now wandering through my twenties and the search for a soulmate is such endless, gorgeous torture. What if it’s him? What if it’s not him?

It hasn’t occurred to me that there’s something infinitely more searing than love that is or isn’t: love that, in another life, might have been. Love that’s simply met with too many barriers, crumbling highways built long ago, trappings of entrenched adult lives: children and en suite bathrooms, promises and time accrued, comfortable rhythms and hydro bills. Love that dances in the negative space, painfully, acutely aware of what it isn’t. Love that arrives too late to be what it could have been, and what it so obviously wanted to be.

* * *

On a bright spring day, my mum is diagnosed with cancer. I am 32. The phone call tears the mountains down.

The disease is spreading, insistent, slow, and black, Earl Grey tea spilled across our cream-coloured dining room table.

The three of us sit around that table late into the night—a table so familiar I could pick it out of a landfill if I were sitting on a star. It has legs, arms, a personality, secrets. We’ve always sat around that table discussing What To Do. Money, divorce, an argument. We solved problems at that table. We talked things into the ether until they didn’t hurt us anymore. In the aftermath of her diagnosis, we are determined that this will be just like those.

My mum wobbles precariously on a burning tightrope, threatening to tip over into terminal territory and leave us on our knees. Then the light changes, and I start to believe she’ll make it. That she’ll somehow reject the absurd, violent gravitational pull of her disease and lean back just enough to fall this way instead, toward us, back into our king-sized bed.

Our days are consumed with hospital appointments. She stops talking as much. Her stories are softer now, and she rarely needs waving arms to tell them. Her hands are cold in her lap. I drive her home from chemo and she disappears into a vacant fog. Is she dying, or off searching for the strength? We all wonder privately, looking out car windows. I drop her off at radiation. I pick her up.

Her cancer is a relentless crescendo. Unreasonable, insatiable. It claims organs, new mornings, and hope. The summer is funnelled into hushed, sterile white hallways and quickly disappears. We learn that her chemo sessions require two support people: someone to sit beside the IV bag and press cool washcloths into her forehead when she vomits, while the other person fills prescriptions, picks up food, deals with parking metres. I run gasping and grateful to my mum’s friends and we build an appointment sign-up system together. Inevitably, the story seeps out of our circle. She is dying when Arthur rings our doorbell.

My mum grips the bannister. Her slippers are way too big for her blue-white legs. She assembled her hospital bag an hour ago. She wants to be on time for chemo.

They hug briefly. My mum breaks away first. She doesn’t hold on to much anymore. Mugs of weak vegetable broth, crossword puzzles on a clipboard. My hands in her hands.

Arthur walks her to his red Honda as though the June grass is coated in thick ice. There’s a plaid blanket folded neatly on the passenger seat, unsure of itself.

I climb into the back seat, where a Portuguese water dog stretches lazily in a splash of hot leather sunlight. Arthur fills the car with an aria from Don Giovanni on a low volume and heads toward the hospital. He stops softly at amber lights. It’s quiet, until it’s not.

With sudden and startling force, my mum issues an opinion about the singer in the stereo. He does this piece far better than that other singer they saw that time, remember? Arthur inhales sharply. No, this singer is just a bit too young, he says. He needs a few more years to be humbled and hardened before he can sing about love with any real weight in his voice. My mum laughs. They dissect the song. They pool their hilariously fragmented knowledge of Italian. They correct themselves and tumble over each other. What was Mozart saying about love?

They sit in the hospital parking lot for twenty minutes, simmering in discussion and debate. The chemo start time comes and goes. My mum’s arms are waving wildly, half theorizing and half conducting the aria. Arthur leans back in his seat watching her, chuckling, agreeing, disagreeing, beaming.

I bury my wet face in the Portuguese water dog, who snorts at the intrusion. I’ve missed this with all my heart. I’ve missed not knowing its name.

For just a few minutes, there is life where there is death and these things argue with each other, yearning to coexist, fighting to be heard, impossibly tangled, one making its case and the other laughing in disagreement. I’m in my mid-thirties now and I know there isn’t room for everything. But for a moment, this unremarkable car on this quiet Friday morning somehow contains it all.