Her heart had healed, mostly, and after a two-day exchange of winningly gnomic messages, she agreed to the stranger’s offer. And so Sebastian (31, jawline), sent a black car piloted by a recent immigrant to collect Erin (29, blowout). Instead of getting lost in the alley and blaming the app, the driver managed to find the front face of the bungalow Erin rented and parked at the foot of the property’s uneven walkway. It had snowed, and the landlord hadn’t shovelled. Erin leapt toward the curb through ankle-high powder, a fawn on tiptoes, hoping in vain the heels of her tights would only dampen, not soak.

When she arrived at the venue Sebastian had chosen—a new, yet already widely celebrated wine bar in the Solar Sidewalk District that Erin had been meaning to visit ever since it’d first been tagged in her neural—the driver opened the rear passenger door and presented a tin of mints branded with a baroque blue and white logo Erin didn’t recognize; snowflakes, serifs, umlauts.

Erin was alarmed. She pointed at her breath. The driver shook his head: No, please, no offence. It is… just in case. He insisted she accept the entire tin. Erin, unconvinced a late afternoon office coffee hadn’t lingered beyond the attentions of toothbrush and gargled antiseptic, flicked open the lid, administered two of the snowflake-shaped mints, then slipped the tin inside her clutch.

The tin rattled as she walked, a maraca off-time from the clicks of nervous flats. Sebastian was waiting in a private room, the cellar, at a small marble table the colour of clouds. He was taller and fitter than his photos. He rose and shook her hand as if they were concluding a deal that enriched shareholders and enlarged year-end bonuses. His grip was a new glove, his palm dry ice. Sebastian complimented her parka, then confessed he’d searched Erin after they matched and had read one of her newsletters on natural wines. He found her prose conversational and witty. Her cheeks found a new shade of pink.

Sebastian knew little of wine, and hoped Erin would not mind ordering. Erin had never before met a man who, when he learned she knew about, well, anything really, but specifically wine, didn’t begin sermonizing, trying to explain the etymology of “terroir” or pontificating about cork politics in a tone meant to sound interesting, but instead signaling one of the more unattractive forms of insecurity.

She selected a skin-contact pinot gris and made a little joke about welcoming the waning prevalence of orange wines. He didn’t understand completely, she could tell, but Sebastian laughed anyway. A genuine laugh. A kind laugh. The creation of this kind and genuine laugh pleased her more than she would have guessed such a thing could. After the server poured a taste, Sebastian asked Erin how she’d describe the selection. She said she didn’t want to sound like a complete asshole, but she was getting a lot of limestone and sea salt and bruised apples.

This last flavour would factor strongly into the account of the evening she later shared with her friend Melissa (30, presentable enough), how after a date-concluding kiss with Sebastian that took place atop Erin’s now-shovelled front porch—their tongues barely touching, their lips cool as snowmelt—Erin placed both hands on Sebastian’s broader-than-expected shoulders and held contact with his outlandishly blue eyes. He closed them. Kissed her again—their tongues still not quite touching—and then whispered so discreetly it seemed intended more for the hairs on the back of her neck than her ears: “Bruised apples.”

She considered fainting. That’s what Erin told Melissa, word for word. “It would have been absurd, I know. But I considered fainting.”

The following months were for Erin like the giddy first few episodes of the second season of a streaming romantic dramedy, when fate gives the enigmatic-yet-still-relatable protagonist the good partnering fortune she’s deserved ever since her One True Love betrayed her for a younger and more vivacious paramour at the shocking conclusion of Season 1. Sebastian listened intently when Erin spoke. Baked her Alison Roman’s yellow cake with chocolate frosting, just because. He cleaned Erin’s bathroom one afternoon while she was out having her eyebrows threaded. They fucked. Everything was perfect.

She introduced to him her friends and their praise was universal. It was the rare match that stirred no jealousy; the women agreed Sebastian was such a good fit for Erin it was as if he were designed for the role. Even Livia (33, microblading)—whose default brand of cruelty was quietly acknowledged in the group as an obvious deflection from her chronic halitosis—approved. It did not hurt, Erin thought, that Sebastian had the good manners to flirt with and compliment each of Erin’s friends, in turn, the correct amount.

Erin told Sebastian her things. About what happened at the party in tenth grade. About her sister’s opinions. About giving up on illustration. He held her as she became quiet before, during, and after each admission. Didn’t offer unasked-for advice or solutions, didn’t prod, didn’t judge. Simply listened. His responses, when requested, after she shared her anxieties and most painful memories, were variations on: “I can’t begin to imagine how that felt.” And then he would wait for her to initiate a hug, and he would receive her, warm and strong and gentle. A panda and bamboo.

They went to Paris. He took her everywhere. Wineries in the near country, Le Select and Le Dingo in the core. At the ruins of Notre Dame Cathedral Sebastian said a prayer. Erin was surprised. He wasn’t religious, was he? Sebastian took a moment before answering. He had been raised Roman Catholic, and though he could not intellectually abide the atrocities and limitless perversions of The Church, it comforted him to continue to imagine there was something out there bigger than humanity that remained unknowable. Was it that different than believing in black holes? He didn’t understand them, either. And they were supposedly far away somewhere off in space, too. Erin supposed that was fine. And she liked that he didn’t simply say “I’m spiritual,” because that was something idiots say.

“But,” he later admitted, when she shared with him her relief at his non-use of this term she disliked for its idiocy, “it’s not a bad way of describing how I feel. Is that embarrassing?”

It was, and Erin found it sweet he admitted it aloud.

They stayed five nights in an AirBnb that was trying too hard. Sebastian had prepared plans for each day, but was flexible about them, too. Museums. Restaurants. A candy shop one of his coworkers insisted was the place to go. And so they went. The highlights were the overlarge European Cadbury bars with unexpected fillings (ribboned praline; cured ham), and the discovery of a small cardboard display of Norwegian mints in the back of the shop.

“I think these are the same ones my Uber driver gave me on our first date!”

Sebastian didn’t respond at first. The skin above his eyes creased, just a bit. That happened sometimes when he was processing information he found difficult. Erin knew this expression. She thought over what she had just said, then laughed as she realized.

“Our first date. Yours and mine. The driver who took me there.”

Sebastian smiled. “Ah.”

Then, using a jokey tone she hoped would assuage any further misunderstanding, she said, “Don’t worry. I would never date an Uber driver.” Sebastian smiled more widely, then insisted on buying her a single tin of the mints. She wondered if she shouldn’t buy two, or perhaps three of the tins, as you couldn’t get them back home. Sebastian argued against it. Not out of miserliness, but of the romantic notion of self-restraint. That perhaps not all consumptive desires need be unremittingly met.

“They’re a special treat. Like you.”

On the second-last night of the trip, Sebastian proposed. That they move in together. Erin was touched but apprehensive. She had lived with a boy once—the author of her heart’s gravest injury—and it did not end well, emotionally or financially. Sebastian understood. His co-habitative offer would remain open, and he would not press for a decision. Erin’s bungalow, after all, was rent-controlled. A price so friendly it would otherwise barely cover a one-bedroom basement. Sebastian recognized this rarity and respected its role in Erin’s decision-making. Erin’s other friends who lived alone often said they would kill to enjoy such luxury. Livia said so with frightening conviction, detailing who she would kill, and how. Erin, who was fairly certain she would never kill anyone, no matter the provocation or housing opportunity, couldn’t quite bear to leave her little den. Not yet.

Three months later, after another lovely weekend (hiking, apple picking, ass eating), Erin changed her mind.

Sebastian hired movers and packers. He sold his bed and couch, and encouraged Erin to select new furniture they’d share. Sebastian paid, his only consideration her happiness, not price. She thought this was too much, and playfully demanded to at least purchase the linens. Sebastian acquiesced. Did he have any types he preferred? He did. A particular brand. He steered Erin toward their site and provided an offer code one of his coworkers had shared. Twenty percent off. At the checkout, she selected the Free Shipping, and chose to receive a further five percent off the order by forwarding the site to three friends. Two of the email addresses she entered were fake.

The third was her sister’s.

They settled into a shared life and its attendant arrangements. Erin didn’t mind vacuuming and offered to captain the household tidying, but Sebastian knew of a cleaning service with a nearly perfect user rating. They enjoyed cooking together, an activity Sebastian suggested they streamline by subscribing to a meal kit delivery program that provided pre-measured and sous-cheffed ingredients. Erin initially had reservations about the amount of single-use packaging the meal kits employed, but their convenience could not be denied, and she continued to use the service even when Sebastian was away, travelling for work.

His field was Compliance, and he politely did not discuss it at length. His company phone plan had terrible coverage outside the city, which limited calls on work trips, but Sebastian was incredible over text. Quick to respond, reassuringly present through notes and photos in the morning and memes and emojis at night. It almost felt like he wasn’t away. And when he arrived home he always brought gifts—little things to let Erin know he was thinking of her while he was in far-off lands, Complying.

From Hokkaido, Sebastian brought a plush anime raccoon that fit in the palm of Erin’s hand. From Doha, dates. In Rhode Island, Sebastian found a set of novelty-sized cell phone lenses. Wide angle, fisheye, telephoto. Erin had such a sophisticated visual sensibility, perhaps her knack for composition could be expressed through photography? To fit her phone the lenses required a plastic adaptor, which she purchased online. She used the wide angle, once, for a few minutes, taking bland landscapes that relied too heavily on an unremarkable sunset. Erin later placed the lenses and adaptor in the junk drawer while tidying the kitchen, thinking about how much she loved her boyfriend for imagining she could acquire a new hobby at this stage in life.

After nearly a year as a couple, Sebastian called out from the en suite to remind Erin about his upcoming weeklong work trip to New Zealand. And did she have a minute to talk? Erin stopped stirring the sauce, setting it to simmer. She wiped her hands on a tea towel bruised with faded reds and wondered if he was planning to invite her along. She didn’t have a particular interest in the country—she hadn’t even seen the Lord of the Rings movies—but it was spring in the southern hemisphere, and she was tiring of what was once again proving to be a positively monsoonish East Coast autumn.

Erin arrived in the bathroom to find Sebastian on one knee. In his upturned palm was a kiwi. With an impish grin, he asked if she would please accept the fruit as a token of his love while he was away. Erin curtsied, playing along with the odd joke, and took the kiwi from his hand. She held it to her nose and inhaled. It didn’t smell of anything. “I’ll treasure it always.”

Sebastian pointed at the bathroom counter. A cutting board and heavy knife had been arranged. He encouraged her to slice open the fruit. Intrigued, she did. And then she dropped the knife.

Inside was a ring.

___

Over the next few days—her foot bandaged, her shoulder aching from the tetanus shot—Erin told the story of the proposal many, many times. How after the first minute of conversation on their first date Sebastian knew they would be married, and how Erin had raved her affinity for the kiwi notes in a sauvignon blanc they shared that night by the glass, and that the following day Sebastian began searching for a botanist to grow the engagement kiwi around her engagement ring, and that the band was only very slightly tarnished by the fruit’s acidity, and would regain its proper lustre in time, probably. She was aware on each occasion she told the story that to do so with the degree of naked enthusiasm she was displaying would be grating to some, and yet she continued, felt like she couldn’t help but continue, possessed by a lightness she hadn’t experienced since, perhaps, childhood?

On the fifth day of Sebastian’s New Zealand trip, Livia invited Erin to join her at her gym. Erin did not particularly want to go. Not just because the YMCA change room floor was a minefield of damp dirty mystery clumps (new-sock-toe-fuzz; deciduous hairs) that were almost as off-putting as Livia’s naked clavicles, and not just because it was a forty-five-minute drive away, but because Livia was always too overenthusiastic about the completion of every rep, no matter how light the weights. Erin found this embarrassing. Erin felt she did not need to “GET IT” every time she squatted with the ten-pound bar. But Livia badgered Erin. Like a badger, digging and digging with sharp little badger claws, until she found a weak point: didn’t Erin want to start getting in shape for the wedding? Erin hated shit like that. Began to say it aloud: I hate shit like—

… but she also did kind of want to get in shape for the wedding.

When they arrived at the Y, Livia showed no interest in the day’s class schedule and didn’t want to warm up on the ellipticals, either. Instead, she pulled Erin by the hand to the squash courts. Dragged her right to the very end, Court F. Pointed at two men playing a clumsy power game, both attempting to control the T for more than two returns, both failing, over and over. Livia was fairly vibrating with excitement. She affected a stage whisper.

“Isn’t he supposed to be in New Zealand?"

The happiness Erin had always felt whenever she saw Sebastian was, at this confusing moment, not present. She brought the fingertips of both hands to the muscles around her eyes, which suddenly felt very tight. It was as if her sinuses had flooded with heavy water. She pressed her orbital bones with ring, middle and index tips. Released, then pressed again.

It did not make sense. Sebastian was supposed to be in New Zealand. Doing Compliance. But he was at the YMCA. Doing squash. She was already knocking on Court F’s glass. Too loudly. The game stopped. Her eyes darting as if continuing to follow the in-play motion of the little black ball Sebastian’s opponent held still under court shoe.

Erin’s mouth was dry. She could smell her own breath. It was coming out in hot little bursts.

Sebastian opened the door. A sharp swing. Smiled at Erin, but not his normal smile—a dickhead’s smile. And then, with a vocal inflection she had never heard before, said: “We got the court ’til 2:15. It’s not even 2.” He shut the door with the curtness of a family man interrupted during dinner by a solicitor. Erin shut down completely.

She and Livia watched the rest of the game from a maple bench pocked with dents and gum. Livia made a number of statements, none of which Erin fully registered. Erin was trying to determine if the man losing 7-4 was indeed Sebastian. It was. It had to be. The other Squash Man kept calling Sebastian “Pete,” but wasn’t that Sebastian’s body, all nearly six feet of it? It was 100 percent his face, albeit covered in a jagged stubble his fastidiousness never allowed. But on the squash court he wasn’t moving the way she knew him to move. He hadn’t spoken the way she knew him to speak. And he didn’t seem to know her at all. He had barely looked at Erin, his demeanour dismissive and snappish, as if he had never once hired a kiwi botanist in his entire life.

Did Sebastian have a twin? A clone? Did doppelgängers exist and were they a verifiable thing, like black holes? Or were they just a regrettable piece of German folklore, like Lutheranism? Livia continued whispering excited theories in Erin’s ear. And Erin continued to let them wash over her, a breeze of casual rancour unheard. Until Livia formed one horrible sentence, a gust of words that smelled of corpse and landed like nettles:

“… or maybe he’s running Admn?”

The nerve. Admn. There was no way. There couldn’t be… could there?

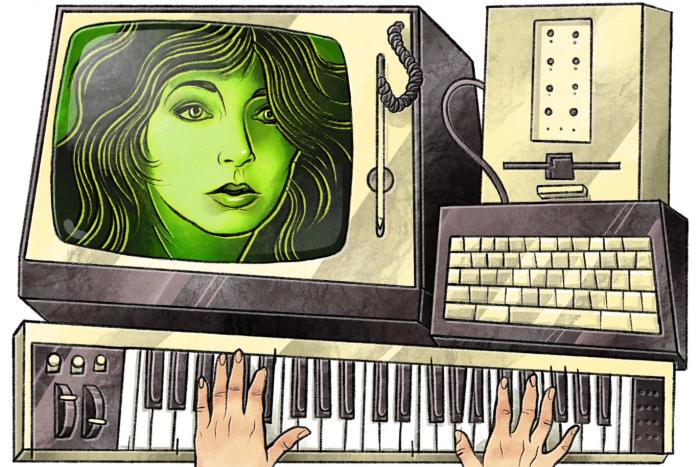

Erin excused herself to the washroom. Sitting in a stall, lid down, not bothering with the charade of dropped pant, Erin searched the Admn site. Ignored the self-congratulatory ABOUT US language and clicked on the HOW IT WORKS tab. Scanned through the text. She already knew the essentials, more or less: Admn was a sort of supplementary operating system for the human brain; airbrushing for your personality. You could install it on your neural—an overall upgrade—just as easily as you could update an older iPhone with the most recent iOS. Then, once installed, you could schedule when Admn ran, the app’s AI taking control of the host body with an algorithm-generated persona. When the scheduled Admn time was over, control of the user’s body was restored to their original mind.

Erin closed the site and searched “Admn” again, scanning through different feeds. Reading snippets, clicking away before finishing. Those who ran Admn were compensated by advertisers in relation to the size and quality of the audience over which the user held sway. In the early days of the app, small numbers of conventionally attractive people of all ethnicities and types unashamedly ran Admn, as the less physically privileged were already programmed by evolution to stare at their Aesthetic Betters, jaws agape, beguiled by what might be done or said. Admn exploited this dynamic, making its users more charming, more thoughtful, and more interesting, amplifying their reach. And while Admn was running, the host had no knowledge or recollection of what the Admn persona did or said on the user’s behalf. When the app wasn’t running—when the user wished to take a scheduled break and return to their normal life—Admn could be set to autopilot, the algorithm maintaining a consistent and distinctive social presence online for the persona it had created, even handling routine correspondence with the user’s audience.

It was complicated. But it wasn’t that complicated.

Was this what Sebastian was doing? Was the man playing squash less than 100 metres from Erin’s closed-seated toilet just a pretty face running an ugly program? Erin had never spent so much energy thinking about an algorithm. The same way she hadn’t paid much attention to sponsored keywords in her email, or a purchased mention of Red Lobster in her most-streamed song ever. These were just things in the world, things that didn’t matter.

She remembered that, for a time, it was unfashionable for established celebrities to run Admn. But after Dame Bianca Li—who had been outed as an Admn user by a former personal assistant who kept a poor calendar—won the Oscar, BAFTA, and Golden Globe (but not the SAG) for her portrayal of a grieving frontier widow who also happened to be a crack shot when rustlers are about, a junta of shitposting tastemakers argued to great effect that it didn’t matter if the world’s most sophisticated advertising algorithm was making Li’s acting choices for her. That the relationship between actor and app was symbiotic, a fusion of her natural physicality and the creative instincts the Admn protocol helped foster.

It was nonsense, of course, but the contesting of nonsense takes so much energy and accomplishes nothing. And after Dame Bianca sailed through the scandal without serious repercussions and Crack Shot 2 opened to a record January weekend, many other celebs—actors, YouTubers, musicians, TikTokkers, athletes, politicians—followed suit. Admn became a shadowy presence in pop culture. Although it wasn’t for everyone and billions of humans went about their days without thinking about Admn at all, the app’s usership had spectacular numbers; gamine teens of every race, beautiful white families with gorgeous white children, and every man on the planet named Tyler.

Just as suddenly as there had been outrage over Admn’s existence, there was acceptance. Like when that research out of Norway appeared in peer-reviewed journals that proved cigarettes cured arthritis. Facts were facts. And it was a fact that even ordinary people could make a decent living running Admn. Everyone has an audience. It could be niche—a handful of dull officemates, a text chain between college friends who no longer have anything substantive in common, a Montessori classroom of no more than seven smug, choice-making toddlers—or it could be exclusive. An audience of one. All income is disposable, after all, and even the smallest target market is coveted by one brand or another.

It was possible, Erin conceded, that Sebastian was running Admn. But it simply never would have occurred to her to ask. It was considered rude. Certain people with the right type of delivery could tease the question in a way that made it seem as if they were being ironic, like casually claiming jet fuel can’t melt steel beams. But Erin was not one of those people. She was earnest. She believed 9/11 was real. She returned from the washroom and took a picture of Sebastian playing squash and held her breath and took another.

A few minutes past 2:15, The Man Who Looked Exactly Like Sebastian exited the court with his opponent. “All yours, ladies.” He walked away. Not Sebastian’s walk. Erin, against Livia’s wishes, did not give chase and demand answers.

Erin waited until she was home to text Sebastian, redrafting in her head the message she would innocently send to ask him how things were going in Auckland. Once it was off, she stared at her phone, her stomach struggling against an insistent undertow. After a moment that felt like an hour, an ellipsis appeared. Then Sebastian’s response. It involved what she guessed was New Zealand slang. Then more texts arrived, a serialized story about one of Sebastian’s team members, Karl, whom Sebastian had previously mentioned to Erin.

Karl had decided to learn to surf, and had gone to the beach in the morning, but he had ignored the warning in the surfing school’s confirmation email about the uncommon severity of the sand flies on the North Island this year and hadn’t bothered with repellant. He was bitten so badly—the coral-red bites swelling to the size of dimes—that he couldn’t endure the pulling of rented wetsuit onto his fly-bitten body, no matter how much talc he applied.

This story had been delivered in sentence fragments, one after another, the *pings* arriving arrhythmically, like elevator cars in the terrazzo lobby of a high-rise that had yet to be struck by planes. All of it was colloquial. Lowercase. No punctuation. It seemed plausible and natural, this texted story, the sort of communication that must have been written by a person. An app that had secured Series C funding wouldn’t misspell “longboard,” would it? Erin didn’t write back right away. Sebastian’s ellipsis appeared once more. Then disappeared. Again. Then gone.

Erin exited her texts. Checked Frndspot. There was Sebastian’s icon, bright blue on the map, glowing at a tiki bar that appeared to overlook Viaduct Harbour. That meant he was definitely there, in Auckland, didn’t it? Or… could Admn dictate Frndspot's location sharing? Who owned these two apps? Did one own the other? How difficult would it be to use Frndspot to spoof your location? She searched briefly without success for an answer, then decided on a more straightforward approach. Erin opened her photos. Selected the clearer of the two Sebastian squash pics, his racquet frozen in follow-through. Chose “Send To.” Scrolled through her contacts. Clicked his name. Thumb hovering—

Then another text arrived. A photo. Sebastian, on a patio, in what appeared to be New Zealand, drinking from a bottle with a label that read “L&P.” She searched it. It was a soft drink brand, Lemon & Paeroa. Established in 1907, native to New Zealand, sort of a sparkling lemon juice. It was now owned by Coca-Cola. Erin pressed her fingertips to her orbital bones again. She was confused. She felt crazy. This was photographic proof. But was it? It could be PhotoShop. Or a deepfake. Erin thought about the behind-the-scenes clip she had watched the previous year about the making of Crack Shot. The climactic scene of the film—a lauded twenty-three-minute unbroken sequence wherein Dame Bianca’s character killed over six hundred men from a makeshift sniper nest nestled in a pecan grove—was entirely computer-generated. Erin maximized the photo of Sebastian and examined its pixels. She had no idea what to look for. Erin swiped back to her photos and thought about pressing send. About confronting Sebastian. About what it would feel like if her suspicions were confirmed. About deleting the photos she had taken earlier that day and forgetting what she had or had not seen at the fucking YMCA.

But Erin did not delete the photos. She made one her phone background—the fuzzier one. She fixated on the unclear image, checking it constantly, willing its soft blur to resolve in her memory as the form of a different man, one who just happened to look very much like the fiancé whose near-perfection she had allowed herself to trust.

Two days later, Sebastian walked in the door. He hugged Erin close and pulled a jar of manuka honey from his carry-on, explaining how everyone in New Zealand swore by this particular brand, and how it would soon be available in North America, but that he thought she might like to try it now before she was reading about it on everyone else’s feed. Erin drained an entire glass of Nova Scotian pét-nat (her third, for courage) and asked the question she did not want to ask, but that had been bubbling remorselessly in her mind.

“Are you running Admn?”

It was like tripping a breaker. Sebastian’s eyes went blank. His hands went to his sides, palms against thighs. He blinked several times. His voice took on a neutrality Erin recognized from the “Admn Safe Mode Reveal” videos she’d watched the previous night. This neutral voice was admitting, under the advertising bylaws of the Hemispheric Economic Community, Excluding England, that he is indeed running Admn. As well as some of the plugins.

Immediately, Erin was crying.

She felt ridiculous. Not so much for falling prey to a yearlong deception made possible by the toothless advertising regulations of the HECEE, but for her hesitation during the two days since she had seen Sebastian’s body playing squash, when she had permitted herself to believe there might be a somewhat reasonable explanation. Perhaps, she allowed—when she shared this story the next evening with Livia, after their third bottle of a swashbuckling Lambrusco—her two-day hesitation was a form of self-preservation? Discovering you were dating someone running Admn was a joke you made. It was something that happened to other people. Stupid people. Idiots.

“I knew it,” said Erin’s sister.

What Erin did not tell her sister is that after a long talk with Sebastian—his speech delivered with the blank candour native to Admn Safe Mode, frankly answering all her tearful, angry questions—Erin decided to continue with the relationship.

Erin kept this from her sister because she did not want to present arguments for a choice she believed had objective merit. That Sebastian, as she was experiencing him, remained who and what she needed in a partner, regardless of which multinationals had played multimatchmaker. What was he not fulfilling? Physically, he was spectacular. Emotionally? Present. Intellectually? They consistently had interesting discussions on a breadth of topics that made her feel like she was the co-host of an interview podcast whose modest success had won the patronage of both stamps and mattresses. And on top of all that? He kissed her mouth, and he held her body like bamboo, and he did the dishes.

So what if he was being operated by an advertising algorithm he invited into his brain? Did it matter who “Sebastian” actually was when Admn wasn’t running? Do any of us ever really know what’s going on in our partners’ minds?

Erin decided we do not, and it did not.

And so Erin and Sebastian continued to be engaged, engaging in the appropriate activities of the in-love and untroubled. They went ice skating on starlit evenings. They went to the movies and bought the fancy seats—crushed velvet recliners to which underpaid waitstaff delivered buttered popcorn and spineless chardonnays. They went to every bar, to every restaurant, to concerts and plays, out nearly every night of the week. They went to overpriced brunches, they went to joyless birthdays, they went to interminable Christenings where children were draped in barbarous tulle. They went to housewarmings, to office parties, and even—against the better judgment of Erin’s nervous stomach—to the cinq-à-sept Livia threw for herself when she was fired for some HR bullshit she blamed on the complainant.

Erin felt the stares from her friends when they arrived, but Sebastian defused the tension by bringing over a 7oz glass of garnacha and referring to himself as Erin’s robot butler while doing a charming locked-elbow motion with his arms, following up the display by conspiratorially suggesting his suspicion that Erin must be running Admn, too, because he’d never met a woman quite so fascinating as she. Erin sipped nervously, her eyes expecting shady reactions, but she needn’t have worried: the girls were laughing with him. They were curious. How did Admn work, exactly? Did Sebastian mind? Was the pay from the advertisers reasonable? What was his real name?

Sebastian demurred, steering the conversation to polite questions about the women’s recent activities as portrayed through highlights on social. The evening proceeded as if nobody minded at all.

Later, drunker than she had been since, oh, university?, Erin told Sebastian—for the first time since discovering his deception—that she loved him still. Maybe even more than before.

Months later, Sebastian and Erin married.

A simple ceremony. Eighty-two people. A forest. The bride wore Danielle Frankel with bone Stuart Weitzman heels. The groom wore a Lanvin tuxedo and Tom Ford Oxfords. All of it was comped, the designers detailed at length in the program. Sebastian’s vows made nearly everyone in attendance cry, and he concluded with a poem some guests recognized:

It’s all I have to bring today—

This, and my heart beside—

This, and my heart, and all the fields—

And all the meadows wide—

Be sure you count—should I forget

Some one the sum could tell—

This, and my heart, and all the Bees

Which in the Clover dwell.

The only invitees audibly unimpressed by the vows were Sebastian’s family members, the ones in unpressed suits and dresses of questionable tailoring who insisted on calling him Pete, who scoffed through the ceremony, rolled their eyes during the speeches, and left during the dancing, handbags bulging with napkin-wrapped cake.

Erin hadn’t been certain about inviting Sebastian’s mother, stepfather, full brother and half-sisters, but she had once read on The Cut that weddings were about the entire family, and shouldn’t she make an effort? Admittedly, the few get-to-know-you get-togethers they’d attempted hadn’t seemed promising. Sebastian’s mother (58, hypertension) made it clear she did not endorse the union and considered the relationship laughable, but at the same time his family wasn’t about to miss what they referred to as “Pete’s biggest mistake ever,” or the open bar.

The latter was Sebastian’s mother’s chief concern on the day. She brought a six-pack of grocery store lager to the ceremony, because, as she explained when she arrived, “Sometimes the bar doesn’t open until after dinner.” She needn’t have worried. The alcohol had been sponsored, too. IPAs and sour beers from a local microbrewery recently acquired by InterBev. Wallace Shawn’s vodka. Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s gin. Instagram’s scotch. And a domestic wine (1, sulphites) enjoyed best/only with a splash of club soda.

Despite everything, despite the wine, it was the most joyful day of Erin’s life. Storybook, nearly. It wasn’t until a few weeks late—the presents unwrapped, the unwanted returned or stored for regifting—that a quiet voice began niggling in the back of Erin’s mind. A voice gaining in persuasiveness, a voice she shushed with cocktails mixed from half-filled cases of leftover spirits. This liquid-y shushing was fine at night and on weekend afternoons beginning at brunch, but on early weekday mornings? In throbbing hungover wakefulness? The voice could not be masked by drink. It was telling her—again, again, again—what she knew and did not want to know: Your husband is an interface designed to sell you more things.

Much of it was obvious: the wedding booze, the clothing, their entertainments. Their food and their housekeeping and their travel. There was no area of their lives untouched by Sebastian’s sponsors. Even what had once seemed so nice—Sebastian returning from work trips with gifts—was, in hindsight, an act of product placement and loss leading. The plush raccoon from Japan? A piece of merchandising for an anime program anchoring a new streaming service to which Sebastian was excited to subscribe. Qatari dates? A key ingredient in the recipes from an interconnected series of hip Turkish hardcover cookbooks. The cell phone lenses that required an adaptor? The adapter was $19. It was made of plastic, and for $30 the company would send two. At the time it felt like an easy decision. What if the first one broke?

Erin hated this early morning nattering voice and its discomfiting truth. On the message boards, other Admn Wves urged Erin to keep the relationship but remove the ads. It wouldn’t be that expensive. It was considered pragmatic. Erin already paid much more each month for her data plan, and unlimited high speed internet didn’t make her nearly as happy as Sebastian did.

So she subscribed to Admn Pro.

It was easy. She created an account. Sequenced Sebastian’s DNA by scanning his toothbrush. Matched it to his Admn profile. Entered her credit card number, selected an auto-renewing subscription, and confirmed the transaction by pressing the pad of her finger to her phone’s chilly screen. And with that it was done.

The only immediate change was that when Sebastian would disappear on “work trips”—which Erin now understood were his scheduled vacation days away from his real job: Husband—he no longer returned with gifts. This did not bother her. This was her choice. And Admn Pro had other features that made the absence of gifts seem a petty concern. Erin came to enjoy tweaking Sebastian’s filters, making him at turns funnier, sweeter, goofier, kinder, more refined, less inhibited, more socially liberal, less fiscally conservative, and—on several occasion—sexually reckless.

In time, however, another change became apparent. Now that Sebastian was no longer surreptitiously promoting brands—now that their union was free from a commercial agenda—they shared fewer activities. Sebastian’s romantic initiative essentially disappeared. On the boards Erin learned this was a common issue; a trip to the movie theatre, for example, was a direct marketing buy by subsidiaries of PepsiCo, whose margins on soda and dye-soaked chocolate made the movie tickets themselves more of a motivating coupon underwritten by the parent company. There simply wasn’t a sponsored reason for Sebastian to suggest leaving the house. And so most nights they didn’t do much of anything at all.

More and more often, when Erin felt like an escape from their somewhat anodyne evenings, she logged into her Admn Pro account and left Sebastian in Safe Mode. Sometimes for days. She would position him on the couch in front of a television tuned to autoplayed episodes of the thirty-third season of a Shondaland series she’d watched to completion several times already, or, occasionally, just a blank screen. It wasn’t romantic, but it wasn’t unnerving, either. It was calm. Easy. Perhaps that was the secret to the continued success of a relationship that stretches beyond first blush? Erin had expected more, but maybe it was like her sister had always said: “Expect less.”

Then, one morning, Erin vomited.

The pregnancy changed everything. Erin didn’t even have to manually override Sebastian’s instincts—he was honestly, fully, completely overjoyed at the news. All of his enthusiasm and joie de vivre returned. He accompanied Erin to the doula appointments with pen and paper, taking detailed notes and asking thoughtful questions. He drew maps of the cowpath side streets near the ancient hospital, just in case. He favourited feeds about baby sign language, baby superfoods, and baby sleep training. He signed up for a baby CPR course. He bought a second-hand sewing machine and downloaded patterns, and began spending his evenings stitching drawerfuls of cloth diapers, decorating each with hand-embroidered baby animals in soft blues, greens and pinks.

One day, while Sebastian was installing a baby gate, Erin realized she hadn’t put Sebastian in Safe Mode in months. She watched him struggle with the device’s poorly designed brackets, the skin above his eyes creasing, just a bit, and felt a powerful, lust-adjacent affection for the father of her soon-to-be-born child. Before bed that night she tweaked his filters again. They enjoyed very little sleep. And a lot of light choking.

___

Livia arranged the shower. It took place at Erin’s former bungalow, whose lease Livia had assumed when Erin and Sebastian moved in together. The decor was tasteful, the canapés delicate, the party games mercifully quick. Sebastian’s mother and one of his half-sisters showed, and, after emptying the punch bowl in the kitchen with eyebrow-raising haste, the women tearfully apologized to Erin for all prior behaviour, begging her forgiveness, impressing upon her how excited they were for Pete to have a child. How they always knew he would be a good father. He was made for it.

Erin’s friends said warm things that afternoon, too, but nobody’s warm words made Erin sob with the same volume of relief and happiness. Not even those of her sister, who had corrected their entire sororal dynamic via a tender speech in front of everyone, an ode to Erin filled with reminiscence, humility, and grace. It was all highly emotional. Erin hadn’t had so much as a drink thus far in her pregnancy, but, when Livia began refilling glasses of Franck Pascal for further toasts, Erin decided just the one wouldn’t hurt. It was a special day.

Erin’s sister drove her home. They hugged inside the car before saying goodbye. Erin exited, her feet steady, her full heart thrumming in time with the littler heart inside. She drifted toward her front door. Erin invited its handle, partnered the door aside, and swept it shut with a choreographer’s panache. There was melody to her entrance, treble clefs and quarter notes in an easy orbit around her smiling face. She floated down a darkened hallway, toward the bedroom, and as she twirled past the door to the home office—

She stopped. Flicked on the room’s light. The office furniture was gone. The desk and printer no more. In their place was a bassinet, a crib, a rocking chair, shelves laden with picture books, walls dressed in watercolour wallpaper, floor draped in high-pile rug. Sebastian had transformed the room into a nursery. Erin explored its treasures like a child snuck downstairs on Christmas eve. She rocked in the chair. Patted the rhino print blanket in the bassinet and stroked the ears of a stuffed koala. Erin trailed her fingers along the spines of the picture books, selected one, flipped through it… and… on closer inspection… it wasn’t just drawings, it included words? Swedish words? Erin frowned. Picked up another book. Same thing—Swedish. A drawing of a dog was labeled“hund;” a unicorn was “enhörning.” Erin—the back of her neck tingling—picked up the koala. Turned it over.

IKEA.

She turned over a fan. IKEA. Flipped over a mobile. IKEA.

She collapsed into the rocking chair, IKEA, the room weaving up and down, IKEA, as she scanned with a more critical eye, IKEA. Every piece of IKEA furniture and every piece of IKEA decor was from IKEA. IKEA crib. IKEA rug. IKEA dressers. IKEA nightlight. IKEA sound machine. IKEA diaper caddy. IKEA play mat. IKEA abacus. IKEA change table. IKEA you get the picture.

In Safe Mode, the sleep unrubbed from his eyes, Sebastian explained to Erin why this was allowed. Admn Pro releases the Primary Subscriber from influence, but Pro accounts cannot be shared amongst family members. Erin felt betrayed. This hadn’t been discussed on the boards. Was she to understand that, from birth—and for the child’s entire life?—Sebastian would be free to bring the full force of his sponsorships to bear on the impressionable minds of their offspring? Unless she purchased a second Admn Pro subscription? What if they had another baby? And then another? Not more than three, surely—she wasn’t Irish, or Portuguese.

The cost of the subscriptions wasn’t the issue. The bump in price from Admn Pro to Admn Enterprise (covering up to five simultaneous audience members) was actually quite reasonable, especially with the loyalty program discount. But how she would explain Sebastian’s absences to the children? How would she explain his periods of withdrawn silences, his inclination to remain on the couch, inert, unresponsive, watching whatever was shown to him for days on end? Could their progeny’s lives have even a semblance of hope or joy or meaning if she were forced to purchase a relationship between father and children free from recommendations, from sponcon, from discounts using the promo code “SEBASTIAN/DAD”?

Erin decided they would not. And that she would not.

Ending it was difficult.

___

Erin moved in with Livia, who helped Erin turn the bungalow’s basement into a bedroom. Livia accompanied Erin to the doula appointments and the hospital, taught the baby to roll over, and was there for the toddler’s first steps. Livia was also there to support Erin’s erasing of Sebastian’s vast catalogue of influence. Erin rid herself of everything he’d ever suggested or gifted, all their shared accounts, all their subscriptions and goods and services. With every brand she scrubbed from her life, she felt slightly lighter, almost absolved. It was a rite of Swedish Death Cleaning performed with Japanese ruthlessness.

Erin even—after some deliberation—rid herself of the case of cloudy North Italian Col Fondo Sebastian had sent over as a parting gift. The gift, like all his gifts, felt tainted: it had come out during the mediation that Erin’s newsletter and its 3,000 or so recipients was the primary reason the Admn algorithm was so interested in Erin in the first place.

Erin’s sister joined Livia in arguing that this case of biodynamic prosecco was the one thing she shouldn’t scrub away. Technically, it was a post-Sebastian product. And natural wine was legitimately her passion. Why not keep it, enjoy? No need to promote the stuff in any way. Even if she did end up loving the vintage, even if she wanted to write about it, who cares?

But Erin was firm. She left the case on the curb, at the foot of the uneven walkway. And besides, Erin admitted to Livia that evening while they drank from tumblers of gin, she no longer felt much like writing about wine anymore, anyway. All the vineyards she liked most were being acquired.

___

Years later.

After dropping Anna (3, impish) at daycamp, Erin saw him for the first time since the divorce. He was walking in the Driverless Car District, near the charging nodes, arm in arm with a woman who was—and Erin was just being honest—quite dowdy? Erin kept walking, a bit in shock, considering whether to turn back, cross the street, and catch up with the pair to let this other woman know.

But then, what if Sebastian wasn’t running Admn anymore? What if he was out there in his real life, as Pete, on a real date with a real dowdy girl? Someone he met at the YMCA? Would it be fair to expose him like that? The private investigation app she’d impulsively used during the mediation revealed the chilling extent of Sebastian’s crippling debt, composed almost entirely of student loans and cancer treatment expenses for his father (55, deceased). Erin tried to keep those details in mind whenever her muted melancholy veered toward anger. Sebastian was simply trying to earn in an economy that was crueler by the day.

Erin took a deep breath. Held it. Released it. Thought about what her therapy app had chanted that morning while she was on the elliptical: Forgiveness frees its giver.

She took another deep breath, and then, for some reason, turned back to take another peek. Erin saw Dowdy kissing Sebastian on the lips. And in that moment Erin didn’t feel like being free. Her therapy app could go fuck itself. She felt like crossing the street without looking either way and shouting at Sebastian in public. If he was Pete, he should hear it, too. She had let her guard down. She had been targeted. She had been bamboozled. She’d never travel to France again. Would never remarry. Would never trust the taste or temperature of her lips. Would never look into someone’s eyes a breath away from hers without wondering about motives. Would never again nearly faint. Would never again eat an ass. That was for other people. That was for idiots.

Just then, it began to rain. Rushes of river appeared, like the world had been in timelapse and was now ramping back to speed. She was already stepping in a puddle of confounding depth. The water was at her knee. Her calf was cold. Her thoughts dark. Her mouth dry and sour.

Erin reached into her purse and felt around for the familiar shape of the tin of Fräschauppa mints she always carried. You could get them anywhere now. She took two.

She felt a little better.