Every week or so, Sook-Yin Lee and Adam Litovitz have a movie date. Then they talk about the movie. Discussed this week: The End of Time, directed by Peter Mettler.

ADAM: [sings] “Picture yourself in a boat on a river, with tangerine trees and marmalade skies…”

SOOK-YIN: Keep singing, keep singing. It’s the background music to my introduction of our Movie Date. After seeing a couple of Hollywood blockbusters and sensing your aversion to formulaic movie-making, we decided to dive headlong into the swimming pool called Canadian independent cinema. Peter Mettler, a singularly unique filmic force—part of the gang of ‘80s Canuck filmmakers including Bruce McDonald, Patricia Rozema, David Cronenberg, and an up and coming Don McKellar—but Peter was the wild card. He was the freaky-deaky one. He’s a weird, experimental filmmaker, more artist than storyteller. He’s put out his third in a trilogy of movies beginning with Picture of Light, then Gambling, Gods and LSD, and now The End of Time. I remember going to see Gambling, Gods and LSD at a rep cinema on Roncesvalles back in 2002, and my body began to slowly metamorphosize in the theatre. I started to recline back, and back, and back, until at the end I was practically laying down in my seat.

ADAM: I enjoyed having my sense of time messed with. It falls into a tradition of art works that play with duration: everything from Proust and Joyce, to other essay and structuralist films. Although I found this one was more a mid-tempo essay film, as opposed to the works of, say, Straub-Huillet or James Benning, who focus on landscapes for really prolonged periods of time. This movie alternates between composed, luxurious shots of a variety of things to hand-held, more conventionally docu-style narration by an assortment of hippies.

SOOK-YIN: All of this in service of the main concept of the film: the questioning of time, our sense of time. What is time? Is it a construct? Or simply a word? Why do we have time? Does time move from beginning to end? Mettler’s on a quest. These are unique films because there’s no script. There’s a tremendous amount of research and exploration—years of travelling the globe.

ADAM: At times it feels like you’re watching your psychedelic uncle’s vacation movies. But I appreciate something that tries to give back time to me.

SOOK-YIN: In the last couple weeks we’ve experienced two pieces of art that altered my sense of being. The first was Leonard Cohen’s four-hour epic performance at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre. I arrived at the end of a hard work day. I was kind of high-strung. The slowness, the dirge-like singing, the very low PA volume—I was like: “Come on, come on, let’s go.” But by the end of the first set, he had me changing my rhythm, and slowing down, and falling into his music. The second set was a transcendent experience. Both men are meditators. Peter’s like: “Just take my movie as a meditation.”

ADAM: It’s self-consciously meditative, which also makes it critic-proof. We’re not supposed to be critical-minded during a meditation. Meditation is all about dropping your facility for analysis and letting things pass.

SOOK-YIN: You really think it’s critic-proof?

ADAM: Yeah, you’re asked to just “go” with various sequences. You’re shown a series of lightning bolts after an equation is made between time and weather, and you’re allowed to create your own sense of what’s happening during that storm, just as you’re asked to participate in a lot of what else goes on during the film. The movie functions as a kind of Rorschach test.

SOOK-YIN: There’s a line where Mettler says something like, “we all see our own unique rainbows.” He reminds me of a more relaxed, less didactic, and less uptight Edward Burtynsky. There’s something about his nasally, low voice that evokes a surfer dude. There was a psychedelia at the film’s heart. I’ve never been able to see lava flow so freakin’ closely. I never even think about lava. This movie forced me to confront the fact that we’re standing on top of the earth’s molten core. Seeing all that slow-moving lava is beautiful yet horrifying—like seeing zombies devouring everything alive in their path—a curious existential situation to be put in.

Most of the people we visit are fringe dwellers, like a hermit living near the lava. They don’t quite fit in but are trying to find their place in the world, and in doing so refute the notion of time. It felt like you were toking with them.

ADAM: It was like the best Burning Man conversation I never got to have.

SOOK-YIN: You’ve never been to Burning Man. It was probably past its prime before you were born...

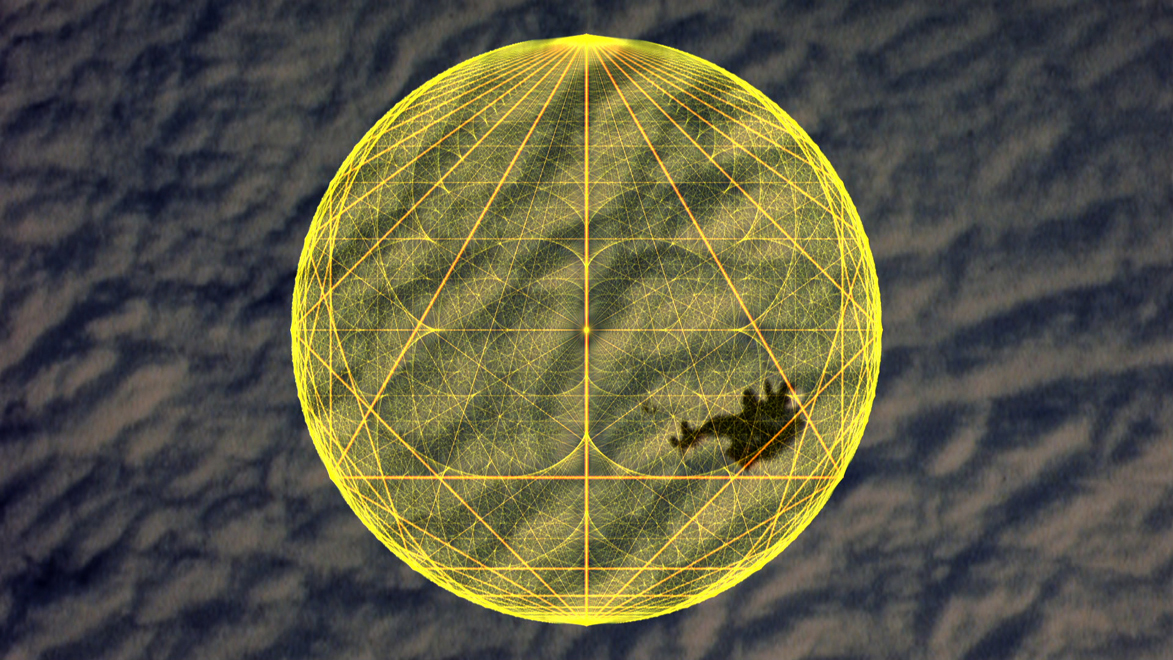

Watching End of Time I was reminded of 2001: A Space Odyssey—with its non-linear, weird, circular examination of time through startling images of our natural world and outer space—crossed with the Pink Floyd Laser Light Show I went to at the blobular Vancouver Planetarium. It’s like a time capsule. That experience was very dated and kind of kitschy. I brought my parents there, and I looked over at two Chinese seniors with laser-light glasses on. They were wearing earplugs and fell asleep during the show. But I found the projections of the celestial universe juxtaposed with “Money” fun. Mettler continues to return to a motif of the mandala. There’s a stunning, psychedelic, wordless passage, that’s maybe fifteen minutes long, of mandalas infinitesimally transforming. That’s when I thought: “we are going somewhere really fucking cool now.”

ADAM: That’s what fractals do. Some of the images were familiar from other exploratory documentaries, like ritualized dance from the films of Chris Marker or Maya Deren, or the intense focus on an observatory, which we saw in last year’s Chilean documentary Nostalgia for the Light. There’s something in the zeitgeist of these essayist seekers that inspires them to look at the natural choreography of the universe, as if to suggest that if we merely attune ourselves to it, we can reinvigorate communal understanding for the betterment of mankind. There’s a humanist searching.

SOOK-YIN: There was a similar quest in Gambling, Gods and LSD. How do we extricate ourselves from the workaday world to find meaning? Towards the end of this movie, I was submerged in an outer space/natural world collision. It brought to mind the work of Tarkovsky, and organic science-fiction movies like Solaris. It’s the combination of that low rumbling score and the rippling water.

ADAM: I was reminded of Solaris, too, in the use of surveillance footage. End of Time was coupling its meditative open spirit with intimations of apocalypse and a paranoid distrust of technology that Mettler eventually forwards in the Detroit section, when he says that technology actually robs us of time. It’s not a far step away from capitalist industrialization that Detroit emblemizes for him, with the idea of Ford’s production line. The movie also puts forward the idea that long relationships in nature are more stable. It’s the idea of cultivating our relationship with nature over time, so we’re not subjecting it to industrial shocks. I was thinking about this idea in terms of monogamy, and what it means to sustain a long-term relationship. How can we differentiate between the length of one relationship and another if, as Mettler suggests, all is continuous and overlapping?

SOOK-YIN: His theory was that there’s more stability in ecosystems that have been around for eons. When an invasive life form is introduced, it can wreak havoc. I don’t necessarily agree with him. When I think of mercurial things, like the jazz of John Zorn, which hurls shards of chaotic, confronting bits, or my favourite art that can be dizzying, it’s no less substantial an experience. Long-term monogamy is not the only meaningful relationship. Something equally sexually powerful can happen between two strangers glancing at one another through a window. It’s not only long, languorous processes that undo time. But that’s Mettler’s preference, because he’s a medium-slow tempo man.

ADAM: There’s that part where he says unequivocally that industrial technologies steal time from us, rupturing our sense of a continuous, long relationship with nature, but there are many ways that medical science, for instance, has prolonged lives. It’s questionable. There are ways in which industrialization might be said to give us time. It’s all about different types of time, never the wholehearted abolition or acceptance of time, but about what time we as a society agree to abide by, or we as individuals experience phenomenologically. It’s a project of rectifying those two things: time as we experience it, and time as is dictated and imposed on us.

SOOK-YIN: He both critiques technology and embraces it. Mettler’s movies are technological but not flashy. They’re the brainchild of an old-fashioned, hand-processed filmmaker. He’s very much an artisan. We’re in a beautiful field with a cat falling asleep in the grass, but as the camera pulls back we realize we’re actually in an editing studio, with the image on a monitor. We realize what we’re seeing isn’t what we think we’re seeing. He’s playing with time.

ADAM: The moment with a group of ants overtaking a dead grasshopper, dragging it into a crevasse, was like a National Geographic take on Dali’s surrealism.

SOOK-YIN: The narration informs us that all of life depends on the devouring of the dead—that time marches on and relies on our ability to exploit and consume the dead. It’s a Joseph Campbell notion. The images themselves are powerful without disparate bits of voice-over guiding us. It felt like he didn’t completely trust us to succumb to the experience.

ADAM: There’s a perilously fine line between something suggestively meditative and utterly adrift. This wasn’t at the point of being entirely out in space. I enjoyed the experience. I can’t return to the feeling of every movie positively the next day. In a climate where so many movies attempt to take your time from you, with simplistic storytelling, at least this tries to remind us about how it’s in our power to re-appropriate time, and to give each other time.

SOOK-YIN: There’s an expansiveness to it. It allows for reflection, though it could have used more internal tension. I was very much taken by a poignancy at the end, where you understand his quest for transcendence. Mettler’s still struggling with the notion of time, and that’s why he continues to make his strange movies. We see a full-circle return to Toronto and his very aged mom on Mother’s Day. She doesn’t quite understand her son, because English is her second language, and because of her age. I felt a fondness from him towards her, being inside his family home where he grew up. There’s a pathos in the passage of time and having to let go of people we love. It was a poetic and tender moment where it became clear what the meandering, years-long quest was about: how to be okay with time and its impact on the body and with death.

ADAM: That’s why the film turned “personal,” so to speak, for the first time at the end, removing itself from that travelogue sensibility, bringing it home.

SOOK-YIN: The movie tries to stave away time. Or, he’s pondering whether it can be screwed with. There’s a spell cast. He’s trying to fuck with time.

ADAM: Or to alleviate our tension, which all meditations do.

--

Illustration by Chester Brown