In a world where superfluous information is increasingly torrential, what could possibly be of less interest to more people than the bestseller list? Weekly, monthly or annually, this is a list of statistics that really can’t be significant to very many people.

Generally speaking I manage to ignore the huge amount of space wasted printing the lists (and there are a ridiculous number of them, with ever more sketchy permutations), but last week my beautiful wife pointed out with a certain amount of glee that The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien, appeared on both the fiction and the non-fiction lists.

In the old days authors and publishers, and editors and agents, used The List as a measuring stick, or a club; authors to beat the publishers into paying more for future projects, publishers to convince authors to stay with the house that so effectively promoted them.

Nowadays, with effective point-of sale capture mechanisms, the bluff is part of the past. All of the interested parties can see just how well, or how not-so-well, a particular book has succeeded at actually making its way into the possession of what we poetically call the end user.

It isn’t always pretty, but it’s excruciatingly accurate, especially in comparison to the way things used to be.

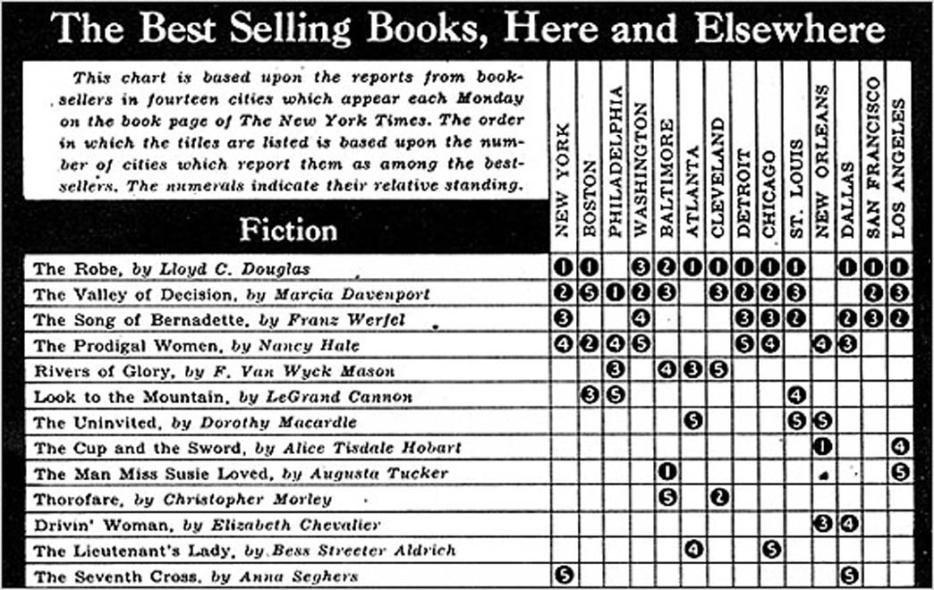

The actual reporting in those days was less scientific. Someone would be employed to call up designated bookstores and ask them what they had sold the most of in a week, and then tabulate the results and put them into some reasonable form.

Booksellers have a rather unusual relationship to many things, and time is no exception. We all have a much better idea of how long a week is that hasn’t happened yet (i.e. the week coming up) than we do of the week that has already happened (that vague, nebulous epoch known as the recent past).

And we’re prone to deny the concrete. If you had 20 and you sold 10 of one title, does that mean you sold more than you did of the title of which you had five but sold all five? Of such existential agonies were the old bestseller lists crafted.

And your eye might be drawn to that pile of a certain title that stood as a monument to your optimistic folly. Perhaps you sold a copy or two of that little barker in the not too recent past.

Occasionally an author with a lot of money would send his minions in to buy up all the copies of his book in order to get it on the bestseller list, providing booksellers with an unexpected boost. These days publishers can report sales directly, bypassing those unreliable booksellers entirely.

Accuracy was a relative notion.

But accuracy, my friends, is not the issue. Accurate or not, bestseller lists are a complete waste of space. Who cares what books are selling, or what books make the bestsellers lists (statistics, you may have heard, are prone to misinterpretation)? The people who do care can see the real numbers. Do you care what books are on the list?

And if, by chance, you do care, do you care any more or less after the book has been on for eight weeks? Is this information that has any value to you whatsoever?

Get rid of the whole idea, I say. Replace those meaningless statistical representations with a list of recently released books that your publication has no space, time nor inclination to actually review.

It’s not as though there’s much information attached to the books on those lists.

“I didn’t think it was a true story,” said my wife about The Hobbit.

“Maybe it’s like evolution,” I suggested. “There’s some difference of opinion and they’re trying to keep the bases covered. Do you think anyone else noticed?”