In the back corner of Sandwich First Baptist Church, 70-year-old Lana Talbot lifts up a loose piece of burgundy-stained wood, exposing a four-foot drop to the dirt floor basement. It’s a trap door, built for slaves who escaped from across the border and onto free Canadian soil. In the past, the church’s bells would ring to warn those inside that U.S. bounty hunters were about to storm the service and drag escaped slaves back to their masters. The targeted slaves would lift open the piece of wood and jump into a tunnel leading to the river’s edge.

Today, a dusty black ragdoll still lays abandoned in the tunnel. At the front of the church, 82-year-old Charlotte Watkins plays beautiful piano melodies on the small stage where her father once gave sermons. In the back, a draft of cold, damp air is freed from the exposed escape, accompanied by an eerie stillness.

“This is history,” Talbot says, looking down into the drop. “This is people’s souls.”

Talbot and Watkins have been giving tours at Sandwich First Baptist Church for over a decade. Located in Windsor, Ontario, it’s Canada’s oldest Black church. With a population of over 600 Black people, the city was a refuge and shelter for escaped American slaves arriving on the Underground Railroad. Built in 1851 by free Blacks and refugee slaves who made its bricks using mud from the Detroit River, today, the church stands tall, a dull orange with worn wooden doors, against the small residential houses. It’s still used for mass and social gatherings that are attended by descendants of slaves, and has become an essential site of Canada’s Black history for people across the world.

Talbot and Watkins both have rich connections to the church. Watkins is one of the last remaining descendants of the original congregation. She is the great-great-granddaughter of Caroline Quarlls, the first person to escape slavery through the Wisconsin Underground Railroad. Watkins’s father, Homer, was a musician and senior deacon of the Church, and she lives on Watkins Street (formerly Lot Street), which was renamed after her father in 1963.

Talbot grew up in Sandwich before its amalgamation as a township of Windsor in 1935. Her father attended the church regularly. He worked long hours tapping steel and came home with burns all over his body. The hot liquid steel would sometimes drip onto his shoes, sizzling as it broke through the fabric. “This was a man who got up every day with burns all over his skin and listen to his boss call him 'Black bastard' and 'nigger,'” she says. “He did that for his family. These are the things that Black people did in this city just to live.”

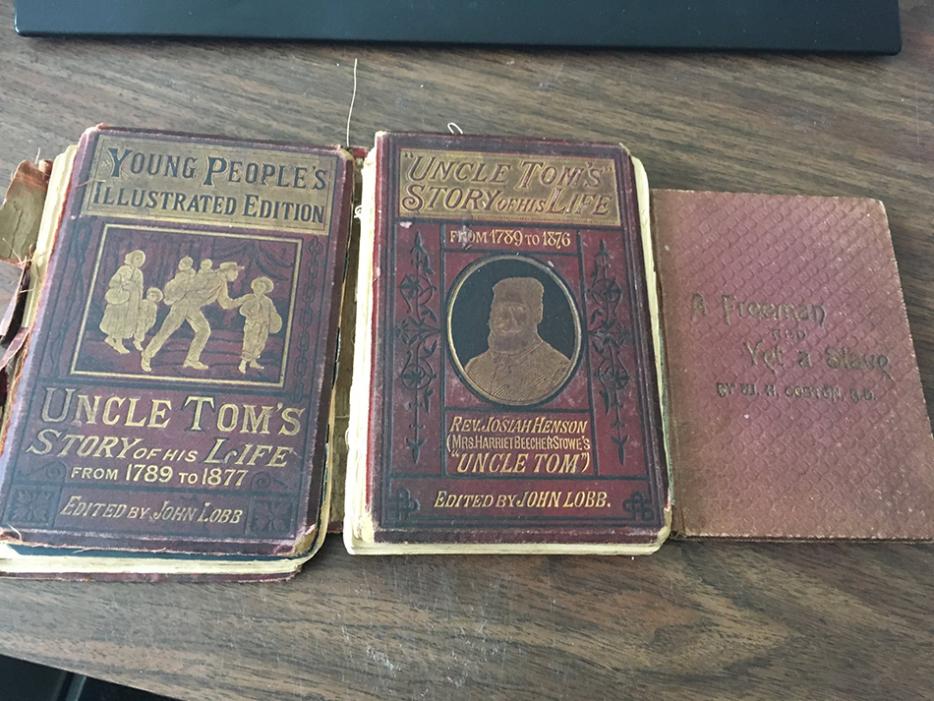

Watkins remembers her own father being insulted and harassed by white hecklers on the street. As a young woman, she argued with him about being an "Uncle Tom" because he told her that she had to be smart and strategic—to live and be successful in this post-Jim Crow world, she would have to act subservient towards white people. However, the church was the one place everyone could be themselves. “The only time I saw another Black face was on Sunday in this church,” Watkins says.

Sandwich First Baptist is one of a group of buildings in Ontario that have been turned into abolitionist museums and historical sites. The museums are operated by direct slave descendants, most of whom are now of retirement age or older. These progenies have spent decades keeping the museums open, educating local residents and tourists across the globe about their families’ involvement in the Canadian abolitionist movement.

These southern Ontario museums are small and as such, they don’t receive even a quarter of the financial support that larger museums do. They must secure numerous grants and donations to pay for expenses. Though by default of their size and location they serve a smaller population, abolitionist museums are valuable resources in the province. At Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum, one of the largest museums in North America, there are exhibits and events such as Of Africa (which required a revamp 27 years ago after it drew criticism for being racist) and this year’s 10-month installation, Worn: Shaping Black Feminine Identity by Karin Jones. The Oakville Museum has an exhibit until the end of the year called Freedom, Opportunity and Family: Oakville’s Black History, but few museums in the province focus on the contributions of African-Canadians.

The United States has over 100 museums dedicated to African-American history in over 37 states (and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture recently opened, now the largest African-American museum in the country). While Nova Scotia, which has a large Black community, has museums including Black Loyalist Heritage Centre and Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, and Saskatchewan has the African Canadian Heritage Museum, most of Ontario’s museums focus on the 19th-century life of white and indigenous people, period homes, natural history, sports and military history. This leaves it to small abolitionist sites in the province to keep Canadian Black history alive.

The descendants, often alongside another family member or spouse, take on multiple roles including curator, director, public relations officer, administrator and tour guide. They are overwhelmed and underpaid, but love the work they do. However, they are getting older and the future of these museums is dependent on finding new successors to curate.

Ontario has about only 20 Black historical museums and sites remaining. They include the Fugitive Slave Chapel in London, the Amherstburg Freedom Museum, Griffin House in Hamilton, Salem Chapel in St. Catharines, Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Dresden, Buxton National Historic Museum and the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society. With limited Black history taught in Ontario schools, finding interested successors from the next generation is difficult.

*

Lana Talbot’s great-grandmother, who was born free, told her stories of the escaped slaves she knew. The most haunting was about slave owners who inserted cork surrounded with glass, razors or pins into the vaginas of slaves to cut their insides when they raped them. “When I see these kids who don’t even know who Martin Luther King is, it gets me so mad,” Charlotte Watkins says, shaking her head. “How are we gonna teach the kids if they don’t know anything?” she asks. “[We] paved the way for you guys. If it weren’t for us, there would be no university, no jobs…we know prejudice first-hand—we lived it so that you guys wouldn’t have to.”

Labeled “Canada’s best kept secret, locked within the national closet” by Black activist and author Afua Cooper, historian Marcel Trudel estimates that 1,132 Black slaves were forcibly brought to Canada by 1759 or shipped through the transatlantic slave trade from other British colonies. Even though John Graves Simcoe, Upper Canada's first lieutenant governor, wanted to outright abolish slavery, the Legislative Assembly disagreed. As a compromise, Simcoe passed the Anti-Slavery Act of 1793, stating that no new slaves could be brought into Upper Canada and that children born to female slaves would be freed at the age of 25. The act was the first to abolish slavery in the British Empire and remained until 1833 when the Emancipation Act finally abolished slavery in all British colonies, including Ontario. By 1844, over 40,000 former American slaves settled in Canada, mostly through the Underground Railroad. Many headed to Upper Canada, (southern Ontario) settling in Chatham-Kent, Windsor, Amherstburg, London and Niagara. They created settlements in these cities, building homes and churches, forging resilient communities and taking in the newly escaped.

Canadian celebration of our abolitionist movement is rarely discussed. School curricula provide brief lessons on Black history, focusing on American historical figures such as Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., or avoid the subject altogether. Growing up, Talbot’s fourth grade teacher put on a minstrel shows in blackface while reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Black students were made to read paragraphs that included the word “Nigger.” “At five years old,” she says, “that does things to a child.”

Since the ‘90s, studies on the exclusion of Africentric topics from school curricula have suggested that it contributes to poor educational performance and low self-esteem among Black students. George J. Sefa Dei, a professor of social justice education at the University of Toronto, wrote a 1996 journal article, The Role of Afrocentricity in the Inclusive Curriculum in Canadian Schools, arguing that a more Africentric curriculum can transform educational structures in Canada by teaching all students about multiculturalism as well as make Black students feel proud of their history. Without this education, the negative racial stereotypes and traumatic history associated with being Black can overshadow the positive. Over a decade later, his opinions and research became instrumental in the creation of Africentric schools in Toronto.

In May 2015, Turner Consulting Group surveyed 148 Black educators across 12 Ontario school boards to understand their experiences with racism on the job. Only 14 percent agreed that their board placed enough emphasis on hiring racialized teachers. Many had negative interactions with other educators, including one teacher who was asked by a colleague to stop focusing so much on Black history since no students in the course were Black.

The study also suggested that the underachievement and dropout rates of Black students in Ontario schools were directly related to the lack of Black teachers. In 2011, visible minorities represented 26 percent of Ontario’s population, but only made up 13 percent of the province’s teachers. There’s no specific information on how many teachers in Ontario schools are black. In the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) alone, 12.7 percent of students are Black, but according to the most recent data from the board, they make up 23 percent of dropouts, while the overall percentage of youth not graduating is only 9 percent. “It is absolutely my opinion that a lack of a Black presence in the curriculum definitely contributes to student disengagement in their learning,” says Natasha Henry, a historian and teacher in the Halton Hills District School Board (in the northwestern end of the Greater Toronto Area). She also says that when Black students don’t see themselves reflected in the curriculum, they fail to see the positive contributions Black people have made in history and society and the barriers they’ve overcome.

A newly revised Ontario curriculum for Grades 9 to 12 for social sciences, geography and history allows teachers more lenience to address broader topics in order to help their students make connections to the mandatory topics already in the curriculum. However, if the teacher doesn’t choose to cover Black history, then students won’t learn it. Since 2007, Henry has developed courses and taught workshops for teachers looking to include more African-Canadian history in their classrooms, including African enslavement in Canada. She has taught over 500 teachers and educators to make their classrooms more inclusive. Henry says teachers want to incorporate more Black history into their classes, but they have several concerns—the main issue is they don’t know what to do with the material and how to incorporate it into an already jammed mandatory curriculum. “Teachers don’t feel like they have enough background,” she says. “We’re talking about incorporating African-Canadian history into classrooms but these are teachers who themselves weren’t exposed to this history as a student.” Language around terms like African-American, African-Canadian and Black is also a major barrier. “They say, ‘Well, if I’m not sure how to talk about it in the classroom, then I won’t because I don’t want to approach it in the wrong way,” Henry says. “They don’t want to say or do the wrong thing.”

“It would be good to know our background and make us proud of who we are as individuals, and proud of what our ancestors have been through knowing they were strong and survivors.”

Rosalie Griffith is a teacher at Westview Centennial Secondary school in North York, Ontario. She runs the Africentric pilot program at the high school and has been teaching for 17 years. She currently runs a Grade 12 standard English class but integrates postcolonial texts, finding that all her students, regardless of ethnicity, are engaged with the Africentric material she incorporates. Instead of choosing a common core text like Lord of the Flies or Of Mice and Men, she chose Things Fall Apart by the late Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe. “It’s important to me and I believe it’s important to my students, but if a student was taking this course with a different teacher, I don’t know if there’d be this focus,” she says. “I think it has to do with the teachers that you have. I build it into whatever I’m teaching, but I don’t think that 100 percent of the teachers are doing that.”

After heated debates on whether the Toronto District School Board should open an Africentric school, the The Africentric Alternative School (within Sheppard Public School in northern Toronto), opened in September 2009 with almost 200 students ranging from junior kindergarten to Grade 8. In 2013, the Leonard Braithwaite Program launched in Winston Churchill Collegiate Institute in Scarborough in eastern Toronto, making it the first Africentric high school in Ontario. Africentric schools teach English, French, geography and math with an African focus while working with the mandatory curriculum.

One of the main criticisms of the Africentric school is that it promotes “modern segregation,” even though students of all races can attend the school and take the rest of their courses with the other students. Carl James, director of the York Centre for Education and Community (YCEC) and a lead researcher on the Africentric Alternative School Research Project, a three-year project with the Africentric Alternative School, TDSB and YCEC, sees it as a way to uplift Black students who felt marginalized and underrepresented in their schools. James cites these issues as contributing to Black students’ dropout rates and poor performance. “They’re not engaged. The school system in which they go to has been alienating to them,” he says. “But it’s also the course material, the curriculum, who’s teaching, the ways the school helps them feel like they’re part of the school—there’s no one factor.”

While the schools have been criticized for having an unfocused curriculum (some parents have complained that it’s not Africentric enough) and low test scores, it’s also said that children have more confidence and self-esteem and are thriving—meeting the outcomes the Toronto District School Board hoped to achieve with the programs. Griffith says it’s essential for Black students to see themselves represented in the curriculum. She remembers sitting in her own Grade 8 history class with a group of white students during their only lesson on slavery. She still recalls her teacher, nervous and red in the face, trying to get through the material while occasionally looking over at Griffith. “That was the only experience I had with anything that brought someone who looked like me into the classroom,” she says.

Kadiatu Barrie, who is in Grade 12, is one of Griffith’s students. She enjoys the diverse material she’s learning in Griffith’s English course. However, she says most of the Black history students at her school learn is American-based and those lessons happen only during Black History Month. While some of her friends are indifferent towards learning more about their heritage, Barrie thinks it can help black students know themselves better. “It would be good to know our background and make us proud of who we are as individuals, and proud of what our ancestors have been through knowing they were strong and survivors,” Barrie says. During a class trip to Windsor in Grade 8, Barrie got to see some abolitionist sites—and it gave her an experience she’s still grateful for. “It was actually mind-changing,” she says. “It wasn’t like when you look for pictures online or a teacher tells you about it. It was so real and we saw it with our own eyes.”

That confidence and Africentric knowledge is what can help Black students take an interest in keeping the history alive. But Nastassia Subban, another teacher at Westview Centennial Secondary, doesn’t think there’s a great enough appreciation yet for students to preserve abolitionist sites. “We have some amazing Grade 12s right now who would be interested in preserving it, but I don’t know if they’d actively go out and do that,” she says. Subban blames the urgency and pressure for students to go into money-making fields like law or medicine, which in turn discourages them from finding their own passions.

Even with Africentric schools teaching black history and a more inclusive curriculum, there’s still a huge gap in terms of teaching it in other schools—and Black youth aren’t subjected to the same Jim Crow racism as Watkins’s and Talbot’s generation, perhaps a reason they see no urgency in preserving the history and sites that established long before they were born. Subban says that teens prioritize taking photos, using social media and playing with their phone above learning about their history and ancestors. “It’s like they don’t know about themselves, but it’s all about themselves,” she says. Henry says this problem is worsened by the failure of schools to acknowledge the importance of belonging and pride for Black students, an already marginalized group. “They think, ‘What does this have to do with me?’” Henry says. “Because if they’re not able to establish this historical context then they don’t know what these sites are. And if they don’t even get an understanding of the significance of the sites and the people connected to the sites then they’ll think, well, what is there to preserve?”

*

Shannon Prince has been the curator of Buxton National Historic Museum, located north of Lake Erie, since 1999. At 62 years old, she is still youthful and lively, dressed in a bright coral blouse, skinny jeans and work boots. Her pixie haircut is stylishly streaked with gray. Born in the house across from the museum, she married Bryan Prince, a farmer and researcher on Buxton’s Black history, in 1979. She was accepted to university for nursing, but soon became pregnant, so she took part-time courses while working on the farm with her husband.

Shannon volunteered at the museum when her cousin, Alice Newby, was the curator. When Newby fell ill and retired, Bryan suggested that Shannon apply. “My first response was ‘I have no museum background. I have no idea how they operate,” she says. “I only know some of the history and that’s about it.”

To her surprise, she got the job.

The museum was built in 1967 by community members to archive the Buxton settlement. In 1849, former slave owner, the Reverend William King, created a 9,000-acre settlement known as North Buxton for free and refugee Blacks. Buxton became the largest and most successful Black settlement in Canada. At its peak, 2,000 people lived here. The population of North Buxton now is only 200 people, mostly Black descendants. Many of its original buildings are long gone, but the history remains in and around the museum. Replicas of slave bunkers, whips, a human branding iron and original iron ankle shackles are on display for visitors. Up the bumpy two-way road, the run-down remains of Papa Prince’s Pleasure Parlour (a neighbourhood bar once owned by Bryan) lays abandoned, as do the only post office and general store in town, painted lavender with windows covered in newspaper. Near the museum is the S.S.#13 Raleigh, the third school to be built in the settlement by refugee slaves and free Blacks in 1861. Though the school closed in 1986, its original sign and pastel blue and yellow exterior remain the brightest sight on the street.

Shannon Prince is a descendant of Buxton settlers and abolitionist journalist Mary Ann Shadd Cary. “It’s that personal connection that we have and can give to visitors. We can talk about our family and their role in the abolitionist movement,” she says. But being a community museum means more pressure. Along with assistant curator and Buxton descendant Spencer Alexander, Prince gives tours and presentations, travels internationally to speak about Buxton’s history and conducts individual genealogy research. They also answer phones and do data entry. “Larger museums hire someone for different departments,” Prince says. “But Spencer and I wear all of those hats.”

Workload aside, there’s the pressing issue of who will make a suitable successor. “We’ve talked about succession planning and we need to include younger voices,” Prince says, adding that the Buxton’s Next Generation committee, a small group of supporters in their late twenties and thirties including the Princes’ own children, teach Black history around the community in creative and engaging ways. The group goes to schools and dresses up in period costumes to re-enact murder mysteries and crucial moments in Southern Ontario’s history including the 1950 string of discrimination cases in Dresden. They host Easter egg hunts and meetings with Santa during holidays. Now that many of them are having children of their own, keeping the stories alive is crucial.

“My mother taught me that if you know your history, you know your greatness.”

Blair Newby, 32, was a member of the BNG before becoming the executive director of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society museum in 2010. Chatham drew in Black people from across North America who heard about how Blacks in the area were thriving in business, education, cultural arts, sports and medicine. Known as “Black Mecca,” the museum was founded by Gwen Robinson in 1996. Located in a community centre, the museum is a small room comprised of a few panels of glass-encased artifacts. An old, boxy TV with a video tape player sits in the middle. Viewers can turn it on and watch on their own. It’s a “self-guided” tour, which may take no more than half an hour to see, but a hidden gem showcasing relics of Canada’s slave past. On the far left, behind the last glass panels, is a door to the office.

It’s clear that no one comes in the office often—the bookshelf is crammed and dusty with binders containing family trees, photos, memories of homecomings, and property ownership. The museum staff help people trace their ancestry and find out if they are a descendant of freed slaves that came to the area, but even the copies of family trees stored in a binder look stained with age.

For 17 years, the museum has hosted the John Brown Festival that honours abolitionist history in Chatham with speakers, music and entertainment. But in 2013, only 20 people showed up. That same year, Black Mecca was left off the list to receive a municipal core grant of $35,000 after getting one each year since 2009, which would have forced the small staff to resort back to volunteer-only positions.

However, in the past two years, the museum has made significant strides. At this year’s John Brown festival, over 100 tickets were sold. They fought to prove that the museum was an integral service for the municipality and tourism, and were once again awarded the municipal core grant. Since then, Newby has gained numerous grants to supplement the museum’s budget, obtained the Museums and Technology Fund from the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport to digitize artifacts and documents, and gained official museum status for the site.

Last April, Newby received her Masters in museum studies at the University of Toronto. While she’s no longer the executive director of Black Mecca (Samantha Meredith, a young history graduate from Lakehead University, has taken her place) she wants to continue working in museums and is currently working in Toronto as an outreach officer at the Multicultural History Society of Ontario and a special events assistant at Black Creek Pioneer Village. Curating runs in her family; Shannon Prince is her cousin and Newby’s late mother Alice curated at Buxton Museum in the ‘90s. “It was watching her that instilled within me a pride in our heritage and a conviction that it’s our job to safeguard it for our future generations,” she says. “If we don’t do it, who else will?”

*

Not everyone comes to curation through family history and many students who are interested in curatorial professions want to go to larger museums in major cities. There are few job opportunities for youth in Buxton and Chatham-Kent, and Prince says that smaller museums are a turn-off to young curators, even for internships. “I’ve put in requests to have students come do an internship,” she says. “But they want to go someplace like the ROM where the job opportunities are better, even though they’d get better hands-on experience here.”

With bigger museums come bigger paychecks. Municipal funding for Buxton and Black Mecca only covers their small staff’s salaries. According to the 2014 Buxton Museum annual report, the total cost allocated to staff wages was $69,600, just enough for Prince and Alexander to divide and scrape by on, and much less than the curator average: according to the Canadian Museums Association’s national compensation survey of 2011, the national annual average salary for a museum curator was $68,559, while a junior curator earned roughly $42,243. Every year Prince goes before city council to ask them to keep funding the museum. “We basically have to prove our existence,” Prince says. “But they’re starting to realize that the museum is an economic driver for the community so they do really want to invest.” This year, Buxton, Black Mecca and Uncle Tom’s Cabin were finally identified as an essential part of Chatham-Kent’s tourism plan.

Young curators may not be willing to take over small abolitionist sites, but there are some candidates much closer to home. Like Newby, children of curators are viable solutions to succession planning. Prince’s four children, all grown, are part of the BNG and help with the museum. “I’m leaving it up to my children to continue my legacy. They will all ensure that they will be here with their families when it comes time,” she says.

The Mackenzie House in Toronto is trying to spark that interest in children. Program director Danielle Urquhart has hosted a successful Black history program for 12 years. The program teaches students of all ages about William Lyon Mackenzie King’s role in Canada’s abolitionist history. They also learn about Shadd Cary and reproduce copies of her abolitionist paper, the Provincial Freeman, using an original 1840 printing press. “They seem to be coming in better prepared for the subject than they used to,” Urquhart says. “Teachers are starting to recognize just how compelling this subject matter is to kids.” Urquhart says the majority of students enjoy learning about Black history, which is good news in the city with Ontario’s largest Black population.

But Newby doesn’t think that’s always the case. “Within walking distance of our museum, there are three public schools and they’ve never come to our sites,” she says, adding that Black Mecca and Buxton get most of their visits from across the border. Newby, who never learned Black history when she was in school, hopes to launch programs to teach students how to preserve museums and inspire Black children to learn and take pride in their heritage. “My mother taught me that if you know your history, you know your greatness,” she says. “I feel that if Black students have the opportunity to learn about their history, they’ll see that they can accomplish more.”

On a February day, a group of Grade 8 students from an Etobicoke public school came to the Mackenzie House, listening to heritage interpreter Bruce Beaton talk about William Lyon Mackenzie’s role in the Toronto abolitionist movement. The TD Bicentennial Education Fund sponsored the visit with the aim of increasing youth accessibility to Toronto's historic sites. Some students got to play hooky because the weather was bad, but others looked forward to the free trip. Sitting cross-legged on an old, patterned rug in Mackenzie’s living room, an iPhone sticks out of a girl’s back pocket and a Samsung phone beeps. But the phones stay put, the kids are attentive and engaged. Even though the burning question is if Mackenzie died in the house, they are just as interested in the tales of escaped slaves and political defiance.

The kids sit quietly for almost an hour. As Beaton wraps up, he asks one final question: “What does education give you?”

A girl’s hand shoots up immediately before her peers even get the chance to think about the question. Beaton points at her to answer. “Power,” she says.

Listen to Eternity Martis speak about this piece on our Cavern of Secrets podcast.