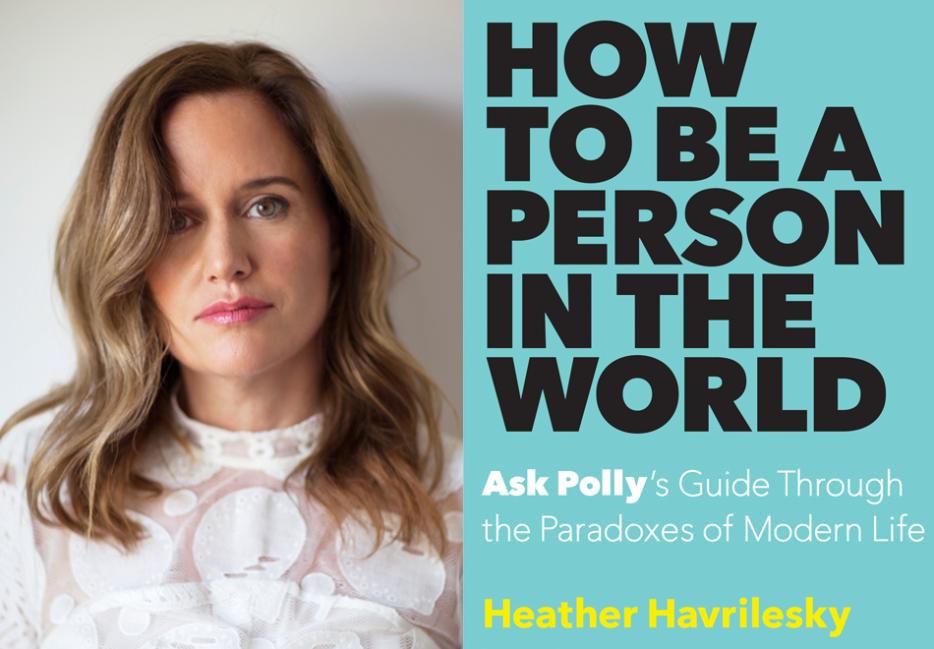

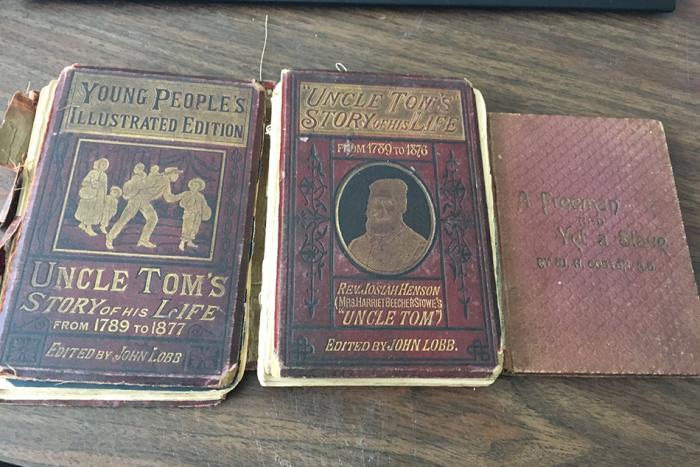

Answering a letter titled “My Mind Likes Imagining Boys,” writer and advice-giver Heather Havrilesky (whose column, Ask Polly, began in 2012 at The Awl, moved to New York magazine and is, as of this week, now a book, How to Be A Person in the World), describes the self we imagine when we’re conjuring a far-fetched seduction scenario. That self is at once better than the real thing (“demure yet straight-talking, slightly more hygienic”) and bound by reality (a “surly, hormonal muse”). This is, I think, exactly what makes a great advice columnist—a surly, hormonal muse whose wisdom is both aspirational and grounded firmly in the reality of our worst selves.

Havrilesky has a gift for situating her advice in our selfish impulses and the culture that creates them, perhaps owing to her decades as a culture writer. It’s our fault, Havrilesky isn’t afraid to tell us, but it’s not our fault that it’s our fault, which, to someone who resists authority, is the perfect motivational package. In Havrilesky’s second book, resisting the urge to fall prey to the shittiness we’ve been coded to accept and enact is a revolutionary act. “The world will tell you lies about how small you are,” Havrilesky writes. She gives us answers, but she also gives us questions (“How secretly furious are you?”) and in doing so, she offers us the space to acknowledge our power to change.

As I turn 30, I feel grateful for the things I’ve figured out and the happiness I’ve found and the luck I’ve had (I’ve also grown extremely fond of soft things, something Havrilesky writes about in a column on the perils of consumerism). That said, I spend an alarming amount of my day employing the title of Havrilesky’s book as a very real query. I’m so often convinced I’m doing everything wrong. I know I’m not alone in this. When I read Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? years ago, I was grateful that a book made space for that question. Now, I’m equally grateful for Havrilesky’s latest, which makes space for some answers. Here, even more advice from the Internet’s favourite surly, hormonal muse.

*

Haley Cullingham: You have a line at the end of the intro to the book about the magic that comes from reaching out. You started writing on the Internet in 1995, and you very much use it as a connective tool, but in the book, you have these moments when you’re answering letters and you describe times in your life when you’ve been very isolated, and so I was wondering if you could talk about the Internet and its power as either a connector or an isolator, or both.

Heather Havrilesky: At this exact moment, I’m very conflicted about the incendiary power of the internet, because of what’s happening in the U.S. and elsewhere. It’s strange because no matter what your particular profile, demographic, and nature might be, you can find people with like-minded desires and goals online, and so I think at the very beginning of the Internet, when I was writing for Suck.com, and I was twentysomething, and young, in some ways I was concerned most with drawing lines between myself and other people. The focus of Suck was in some ways a little bit harsh, and in some ways kind of honourable for its time, calling out the kind of stupidity that was running rampant in the early days of the Internet. There was a lot of money being thrown at crazy, glorified advertisements, essentially. And so there was kind of this sense that this tool, that had all of this amazing potential, was going to be turned into a giant shopping mall. When you’re young, when you’re in your twenties, a lot of what you’re focused on is forming a clear identity, and finding your courage of conviction, finding what things you feel should define you and figuring out what things are apart from you, and separate from you, and different from you.

And then I was a critic for years, a TV critic, and then a book critic, and then a cultural critic, and again, a lot of my energy was focused on separating the really crappy TV and lame cultural artifacts from the good stuff, and defining what makes something good and what makes something worthwhile. I think that my advice column kind of started out along the same lines. And certainly I still write about culture in the advice column. Many times I write about it as this force of evil, toxic information that tells you bad things about yourself, particularly—I don’t even want to say particularly women because I think that our culture reduces us to our lowest common denominator. It’s easy to get the impression and to tell yourself that you’re nothing until you prove to the world that you’re something, especially against a backdrop of social media. It’s really interesting and gratifying for me to do something that is sort of more about describing human potential, and capturing an individual’s potential and expressing it in ways that will actually inspire the person to reach that potential. It’s a little bit unfamiliar to me, and I think that’s why I love it so much. It’s very challenging, but it makes me stretch and grow as a person to try to do it.

As you’re answering the questions or thinking about writing the answers to the questions, does that help you work out your own stuff? Or is it more isolated than that?

Oh yeah, absolutely. I think it’s hard to have a practice that keeps you in touch with what’s important in your life. I’ve never been good at meditating, I am not dedicated to yoga—I prefer running to yoga. And I’m not religious, I’ve never completely bought into many spiritual ideas—at least, spiritual ideas that came at me from someone else never felt compelling.

Was your family religious growing up?

My dad was Catholic and his family was Catholic so I was raised Catholic, I went to Catholic elementary school and then I went to public school. My mom was an atheist, or agnostic, basically, and made it very clear that she was agnostic throughout my childhood, so it was sort of like, if I asked about heaven, my mom would say, “Well, some people think that people go to heaven.” She was sort of willing to give me that comforting illusion but it was pretty obvious where she stood. So I always have a little bit of confusion and skepticism around religion, and having been raised Catholic also, it’s very easy to turn against the Catholic faith because there’s a lot of suffering, there’s a lot of kneeling on hard wooden benches, hard wooden little kneeling stools, and there’s a lot of sitting in church and listening to people together confirm their faith as a group, which, as a natural skeptic, forces you to question whether these things are true. I always found the “We believe this, we believe that” … it always struck me as incredibly freaky and scary that everyone was agreeing. I was definitely raised by two people who were in some ways beyond reproach and completely formed their own ideas about what was important and what wasn’t, so that informed a lot of my natural non-joiner instincts. I am the definition of not a team player.

What you said earlier, that idea of culture forming us to have sometimes terrible perceptions of ourselves, do you ever find it challenging to balance your own politics and ideals with things that you observe in human behavior to be shitty but true? Do you ever, almost, want to present the world as better than it is? That idea of, “Maybe if I pretend you have a bit more agency in this situation, that will actually come true, because a lot of people read my column, and maybe I can change the way that people think!”

Believing you have agency is, I think, the only way. My belief in each individual’s agency is pretty strong. Obviously it’s hard to completely process all these letters from people who feel very strongly that they don’t have any agency in their lives and still come out with this idea that anyone can change their circumstances. Not everyone can change their circumstances, obviously. I don’t answer letters from people who are imprisoned in a foreign country. Once, I got a letter from a guy who had chronic back pain, and I wrote to him, and I asked him all the things he’d done and he’d tried all these things. I mean, talking to someone with chronic pain is really intense. Talking to someone who’s dying is really intense. There’s some acceptance that has to go on there, but it’s, you know. In some ways, people who are in situations that are torturous and never-ending, it’s a really hard thing to even fit that into the shape of the column. I don’t really take that stuff on, for a reason. It doesn’t really fit. So obviously not every problem is 100 percent solvable using only the powers of your imagination and your brain.

But, that said, I am definitely a firm believer in individual agency and also in human potential. Even if you can’t actively change your circumstances in the moment, so much of our experience is dictated by how we perceive and how we feel about the world and about ourselves, and that’s something that—you asked if the column helps me, yeah, it is kind of my practice now. There aren’t that many great ways for me to remind myself what’s important, and the column serves that goal very clearly. My experience of myself and the world has shifted dramatically since I started writing the column, actually. If I had to talk about this advice column four years ago, or three years ago, two years ago, I would have struggled to do it with any kind of clarity. My whole experience of my own happiness and the way I move through the world has shifted hugely. My circumstances haven’t changed that much. I had everything I ever wanted, really, when I started writing the column. My work was a little bit sporadic—I was very successful, I had very good gigs, but I wasn’t working enough, and I felt that. I was a little too under-occupied. I could have gone out and gotten a gig; I knew that I didn’t want to write about TV anymore, so I wasn’t sure what I was going to do, and I was driven a little crazy by my work patterns. I had a three-year-old and an almost-six-year-old—there’s a certain kind of weird crucible that happens when your kids are around those ages, and I was a freelance writer, and a lot of things felt up in the air. But I had everything I wanted. I had a husband that I loved like crazy, I had kids that I was crazy about, I had a stepson who I was crazy about, everything in my life was right, but I didn’t feel that good. I was finally forced to ask myself, why can’t I enjoy what I have? And I feel like since then, I’ve learned to enjoy what I have. Because I have to write about happiness, I’m not allowed off the hook. I’ve got to live it or it’s all bullshit. So I feel like I’ve been crawling towards a new kind of happiness that I haven’t really experienced before in my life. And I feel like the things that I’ve discovered have been kind of amazing and important and incredible, and now I talk in ways that I wouldn’t have recognized four years ago. As someone who used to be led primarily by my intellect, I’ve become someone who talks about feelings as the most important thing.

One of the things I felt, after reading the book, was very grateful for the things I had—it gave me that feeling.

That’s so great, because that’s a huge part of what I’ve learned to do, and what I feel it’s important for me to preach in my column. Our culture teaches you that you have to get somewhere, and then once you’re there, you’ll feel it all. But you won’t feel much, you’ll just feel the struggle, until you get there. And what you learn, when you start to get somewhere, is that there is not there. Simply passing one finish line or another doesn’t do much for you, actually. What led to this, one of the pieces of it, was I published my first book and I wanted to feel some satisfaction in having done that, and it was very hard for me to feel the accomplishments around that. I couldn’t let them in. I wasn’t accustomed to standing back and appreciating things. That wasn’t part of my daily habit. And now it’s part of my daily habit to appreciate weird little things. Because if you can’t appreciate the small things, the big things come and you feel terrible, actually, because you feel like a robot that can’t even process this big thing that’s happening to you. A feeling of visceral understanding that this moment is all you have, and you have to recognize the beauty in the imperfection of this moment—that’s really at the centre of what I feel every day and believe in and what I’ve learned to savour, and it’s what I’m trying to communicate in almost every column.

The book has 24 original columns that weren’t online before. Was there a difference in choosing those letters, and answering them, when you knew they were for the book, versus strictly for your column?

I actually just wrote a lot. I would sometimes be writing a column for the website and I would say, "You know what? I really love this one. This one should be in the book." When I was writing for the book, I would just answer a lot of letters. I probably answered three or four a week around that time, and then one of them would go to the column. And the column actually got short-changed a little bit, for a few months there, honestly. It was still pretty good, it’s just, the very best stuff, I was selecting out, and saying, “This deserves to be in print FOREVER.” I set out with this vision of very deliberately writing this so one column would build on the next column and it was all kind like a crescendo at the end of the book. But instead, it was very hard to do that, and when I found myself saying, “This one’s going to build on the last one,” I couldn’t quite pull it off—it was like, “I don’t even know how to make this chapter on sexual harassment build on the one about the girl who doesn’t want her sexy sister and boyfriend to come to the wedding.” So really it was much more haphazard than that. And so in the organization, we tried to do the same thing, the organization of the book works really well, I think. It does kind of feel like this descent into serious heaviness, but also the epiphany kind of builds as the book goes on.

It sneaks up on you, and when it starts getting heavy you’re almost ready for it, you’re primed.

Yeah, you’re prepared, right? Because you've kind of been through the whole therapy already. It’s weird.

Is there a form of writing that’s most comfortable for you?

There are different comfort zones that I get into. I know how to write a critical piece—I’ve been doing that for years, so I can sit down and write a catchy lede and jump right into an analysis of a book pretty quickly, and I enjoy it a lot. Easy is a weird word, but nothing flows more for me than writing the Ask Polly column. I just think it pulls together a lot of my strengths as a writer, and as a thinker. As a feeler. That sounds fucking terrible. I think that I’ve always wanted to write about the human condition and big themes, and I’ve always sort of forced that onto my analysis of The Real Housewives of New York, for example. So if you look back at my TV column for Salon, I was always trying to push it towards things I was more interested in. Most of my approach for writing criticism is in fact, like, start with an idea big enough that it captures my interest, and then I could write the rest of the piece. If I started too micro, if I started in the little details of the artifact itself, I would feel like an academic, almost. I just get bored quickly. So I’d start with a grandiose lede so that I felt like I was taking on something big. I think I always wanted to write directly about love, and trying to find meaning in your life, and trying to understand yourself, and trying to be understood by other people, and the frustrations of being alive. But as a writer, I’m sure you know, it’s hard to get to the things that you really want to write about sometimes, because you can’t just send your 5,000-word essay on love to an editor and get it published. Unless it’s love as reflected in Beyoncé’s Lemonade. So I feel very lucky to have a platform to write the things I’ve always wanted to write.

I’ve always been, at heart, a non-fiction writer. I wrote essays when I was really young, when I was in college. The form of the essay has always come naturally for me, against my struggling with fiction and my struggling with poetry and my struggling with other forms. So, this feels like a natural extension of that affinity, and also a natural extension of my focus in life. I’m that friend who’s seriously fucking heavy in person, and just wants to hear about the heavy shit that’s going on in your life. I’m also the one who, if you call me and say, “I feel like everything is falling apart,” I’m like, “Oh! Tell me more! Fascinating! Wonderful!” I’m the opposite of the friend who hears that and says, “Jesus Christ, I’ve gotta go.” This feels like a natural extension of what I’ve been doing forever, in my free time, unpaid.

Is being an advice columnist like being a doctor, in that once you start doing it, everyone calls you and asks you for advice? Or are people now less likely to ask?

People ask me for advice. It’s really great, actually, because no one took my advice before. No one wanted to know my opinion of anything, honestly. Except TV. And I never wanted to talk about TV, so it was hard. People would stop me at parties and say, “What are the good TV shows?” and I’d be like, “Ugh, go read my column, I don’t know, I don’t want to talk about that.” But now, it’s hard to have a conversation with someone who’s read the column who doesn’t tell me everything about themselves at some point, which is my version of heaven. I love that. If you’re someone who is always craving that kind of interaction but you don’t get enough of it, it’s always glorious to stumble into a world where people tell you things. AND take your advice seriously! That, in and of itself, is like, what? Why do you want to know what I think about this? This is amazing!

It does feel like there’s a natural relationship—maybe this is my twisted brain—between reviewing reality TV, and giving advice. And even reviewing narrative TV. Here’s how we think humans behave, here’s how they actually behave, and you’ve been in both those spaces and written about it. Is there a connection between those things for you?

Definitely! When I watched a ton of reality TV it was always just to psychoanalyze everyone on the screen and parse their motivations, and also see how they took these raw emotional states and translated them into blame and incendiary rhetoric and insanity. My husband and I used to love that stuff. We would watch a lot of it. I mean, I did have the excuse of being paid to comment on things like that, but in earnest, I loved it like crazy. Loved that stuff. And also, since The Sopranos and Six Feet Under were starting to delve into the psychological, and in Mad Men, they were explicitly about the psychology of these characters. I had been shoving my dime-store psychoanalysis into almost everything I’d written for at least a decade, so it didn’t feel that unfamiliar to branch into this.

I think that any good writer brings everything, the full force of their personality, to the page. The memorable writers you read are writers who really show themselves. They find ways to show themselves. They don’t need to talk about themselves in order to bring something new to the picture. Thanks to some really interesting, great, brave Internet publications, people like me have been able to find a voice online that we probably wouldn’t find in print that quickly. There’s less freedom in print, I think. So I feel grateful that I was allowed to be a freak online at a very young age. After my experiences at Suck.com where I was allowed to just be completely mad, crazy, and funny and strange and smart and harsh, I really had a certain confidence that I could bring a lot of different things to anything I was writing. That I could infuse anything I was writing with a lot of fun and madness to keep me interested. I think that the best writers are people who are bored by a lot of stuff. I wouldn’t be a writer if I just had to write really rote—I’d rather write press releases than write just a rote reaction to something that is just the expected take. And I think TV criticism for me started to feel that way. The field was so flooded that I didn’t really see what kind of value add I was bringing to the table at some point. There are a lot of brilliant people writing about TV now and I don’t think I’m adding much to this picture.

I don’t think I’ll ever feel that way about advice. I do think that probably there’ll be ten times as many advice columns in a few years as there are now—people are really interested in this kind of subject matter and I think part of it is just that vulnerability is becoming more mainstream, and things that were once seen as soft or feminine are becoming more socially acceptable for everyone, thank god. Emotions are acceptable to express in some strange corridors of our culture finally. But Ask Polly feels special to me: it doesn’t feel like something that will ever feel like an average or rote writing experience. I believe very fervently in the notion that I have something to offer in this realm.

Something that you spoke about on the Longform podcast is the idea of negotiating. I wanted to ask you about it because it’s one of the things that writers ask me about most often. I’m wondering if you have any advice on how to talk about money professionally?

In the Longform podcast did I talk about how bad I was at negotiating? Oh, I talk about how I was good at it when I was younger and then I got really bad at it.

But then you talk about how you did it successfully when the column moved to New York magazine.

Yeah, I did, when they approached me. Well, they wanted the column, and I actually didn’t really want to leave The Awl, so that helped. This is a good starting point for my answer because when you’re young, one of the liabilities of not having enough experience is, you want every opportunity you can take and you feel like you don’t have any leverage because you don’t have a lot of options, or you feel like you don’t have enough options. I think the people that I see who are the best at negotiating are the people who understand that they have lots of options. And part of that is just doing work that you’re really proud of. Do work that you know is ten shoulders above a lot of the work in your field, and part of that is informing yourself and having a lot of knowledge of what’s out there, and also taking in and understanding the different kinds of styles and voices that exist, and understanding your market, and understanding, this is the kind of thing that I can write, these are the basic requirements of this form. If you’re writing for a print magazine, if you’re writing for certain places as a young writer or as a less-experienced writer, if you approach and you say, “I just want to write about shame,” or, “I just want to write about something kind generic,” as a young writer you have to say, “I’m going to tie this to this cultural artifact, or I’m going to tie this to this event.” Knowing the basic requirements of any given publication before you approach them is important. That sounds super basic, but if you’ve ever been an editor you know that that’s the first obstacle you have to clear, or the first hurdle. It’s not a given that people know that a piece can’t start out with, I’ve been thinking a lot lately about nuh-nuh-nuh. David Sedaris can write that piece but no one else can. It will get read and published if David Sedaris turns it in, but anyone else, including me, will not get that published.

But also, I think, the people I know who make a lot of money from their writing, a lot of what they do is they tirelessly approach every place on earth, and they approach with their best work, that’s been edited a million times, and they get all these people interested, and then they have options. If you’re really a workhorse, and you’re writing for a ton of different places, you know that you have options. And each time you get paid more, it’s easier to lop off the bottom rung of payers. I mean, just two years ago, I was making completely different kinds of money than I am now, and part of it was just, at some point—and I loved writing for certain places that didn’t pay well, I just loved the place—but at some point I just had to say, what am I really doing? Do I want people to read my stuff? Do I want to get paid? Do I want to work my ass off around the clock for half the money? Because there is such a wide range that people pay these days. And then there’s also the competing thing—people sometimes treat the really high-paying gigs, like feature writing, as the ultimate goal, and you have to know yourself and know what you actually want to write. I don’t personally want to fly around the country writing features. I’ve never wanted to be a reporter, that’s not really who I am. But there have been times when I’ve been tempted to walk down that path simply because those pieces pay incredibly well, and anything that’s kind of seen as the elite tier of what you do, it’s easy to get tempted to fall into that stuff. But you need to know what you particularly have to offer, and you need to know what you want to write when you wake up in the morning. Knowing what you really love to write is half the battle, and then when you know that you’re one of the best at writing a certain kind of thing, it’s easy to ask for what you deserve because you know that what you have is worth something to a lot of different places.

We’re in a little bit of a bubble right now so it’s not that hard, if you’re writing great stuff, to get what you want. I think that’s going to change, it always does change. It always constricts, there are contractions, and then you don’t make any money again and you’re like, “Oh my god how am I going to pay the bills now?” I’ve been through so many of those ups and downs since 1995, when I started. But when there is a bubble, you’ve gotta take advantage of it. There’s a big content bubble right now and you’ve gotta hop on that, hop on it. And ask for what you know you deserve. And obviously part of it is knowing what other people make, which is really hard to find out. You can just skip all that bullshit, because I just rambled for ten hours, but here’s a really good anecdote: I’m writing for this place, I know they value my work, and a friend of mine sends them a similar piece, and they offer her twice as much money as they offered me. This friend of mine has arguably fewer clips—very talented, arguably less experience—and I had a relationship with this place and she didn’t. What I learned was, walking in the door, this person is being offered twice as much as me, so I’ve done something to signal that I will take whatever they give me, which as a woman I think it’s just so easy to let your guard down and do that. And I didn’t change my relationship with the place, I went to them and it was just a transparency situation where I said—luckily my friend wasn’t against me doing this—but I said, look, I just found out that you offered my friend double what you offered me for the same exact piece, we were writing similar things for some issue or something, and I was like, I just need you to know that I have this information, and I need it to be understood that I don’t want to be taken for granted. And you know, if you just make it really clear, you can’t get angry, you just have to be very clear: this is the information at my disposal, I present this without commentary, I just want you to understand that I need to feel taken care of in this situation, and the response was extremely understanding and I got paid a little more, and a little more care was taken in how I was treated from that point forward. Being honest without being incendiary is pretty important.

Now, when it comes to negotiating, when I was younger I would just say, “I want twice as much as I’ve ever heard of anyone making,” and then I’d get half as much. People would laugh in my face, and then they’d still give me a lot of money, because I’d asked for an obscene amount of money. I think that’s pretty risky—I don’t think that always works. It depends on who you’re dealing with. But certainly, when someone offers you a laughable amount—unless you absolutely need the experience, unless you really don’t have any experience at all, in which case there are times when it pays to get experience, having published clips is important, if you don’t have any published clips at all, you take whatever a few times, and you keep writing great things, and you keep working really hard, and you understand that you’ll get paid more—but when people offer you a laughable amount and you’re an established writer, you can’t even go to the table. When people offer you a stupid amount, you don’t show up at the table and say, “Okay I’ll take a hundred dollars more than that,” or whatever, you just say, “I’m not really working for that.” I’m not picking up the pencil, so to speak, for that kind of money. One thing I do do is, when people approach me, I say, “How many words and how much are you paying?” immediately. I’m not going to get into a protracted negotiation about what I’m writing until I know exactly what’s on the table. If people come back to me and say, “We’re paying $150,” it’s like, you should know that I don’t really make $150 for a piece. I can’t really do that. And it feels good. It feels good to flat-out know. And it’s not very good for small publications that want good writers, but you know what? There are a lot of good writers out there. They can find them. It doesn’t help anyone when people take less than they’re worth. It’s good for people to take what they’re worth, especially really good writers. When a publication won’t pay you what you’re worth, when you read things on the site that aren’t good, that are shittily written, that tells you something. There was a point where I was writing for a place, and I looked at everything on the site and it was all shit, and I said, these people don’t value quality, so why the fuck am I writing for them?

Conversely, there are elite publications that don’t pay well, but you love everything on the site, and you think, I want my work to be in there, so I’m going to take a little less, because I want to be in this crowd of good people.

The value of being a part of that ends up making up for the money you’re not making.

It is worth something. It’s good to be associated with great places, with people who have a lot of ideas. I’m not saying take shit for money over and over again, but where you’re published does matter, especially when you’re starting out, and making a name for yourself in the right places does matter a lot. The other thing is, being in places that aren’t afraid of strong voices is really helpful because it helps you to form your voice. You can take risks without feeling like you’re just conforming to some kind of overarching we that’s not quite appropriate. When I wrote for Salon, there were a lot of good writers there, but my voice was not completely in line with the voice of Salon, it was a little different, and in some ways I think that served me well, but starting the advice column, starting Ask Polly at The Awl, really formed what Ask Polly is. If I hadn’t written Ask Polly for The Awl straight out of the gate, if Ask Polly started on a woman’s magazine, for example, a monthly print magazine—Elle has a great advice columnist, E. Jean Carroll—if Ask Polly were written for a woman’s magazine, it would not have become what it is. It would not have had the strong, strange, weird voice that it has. The early Ask Polly columns were just madness—jokes and anger and rambling insanity. So that’s part of its DNA, and it evolved into something great from a half-mermaid, half-wooly mammoth, to whatever it is today. Something that’s a bit evolved from that I guess.

The last thing I want to ask you about is kind of general. I wondered if you could talk a bit about empathy. Do you think most people are empathetic and capable of empathy?

Yes, they have the capacity for empathy. But I think empathy is an underdeveloped muscle for most people. Empathy for others begins with empathy for the self, and one of the biggest afflictions that I see that’s common to most of the people who write to me is they don’t have compassion for themselves and they don’t give themselves credit, and they don’t let themselves off the hook, and they don’t rest. They’re caught in a loop of intellectualizing everything that happens to them, and trying to solve their emotional problems through more mind puzzles, and through more intellectual punishment. It’s a trap of being an intelligent person, that you think that you can control reality by thinking your way to some intellectual solution. And that DNA is also built into my column. There’s some intellectualizing, obviously, it’s on the page. I am quite clearly someone who has overthought every single thing that happened to me for decades. But when you beat yourself up with your own thoughts instead of giving yourself some space to feel the things you feel and to be where you are, it’s really hard not to beat other people up for the choices they make. When you give yourself space, to be who you are and to have flaws and to make mistakes and to crawl slowly to some kind of understanding and solution, and when you recognize yourself as someone who is blind to many things, when you realize that you’re just this humble soul that’s struggling to understand the world, and you allow yourself to be that without judgement, without paying a price for it over and over again, then you naturally look at other people and you can accept them for who they are. Until you fully accept your own flaws, though, you won’t accept flaws in other people, you won’t empathize with where they’re coming from. Instead of seeing how they’re feeling and the struggles they’re going through, you’ll only see how they’re getting it wrong. And we’re sitting in this moment in history where there’s a lot of finger pointing, and a lot of people calling out other people for the ways they’re doing it wrong, and it all looks like a war of a lot of self-hating parties to me, from a distance.

It’s not a groundbreaking idea, having compassion for yourself. It’s actually the basis for a lot of religions. It’s an ordinary thing, it’s a mundane art. But once you start practicing the art of compassion for yourself, it really transforms the way that you encounter other people and the way that you proceed forward. It’s a way of feeling your feelings. It’s a way of savouring what you have from minute to minute and from day to day. It makes space for that experience. So instead of being locked in this neurotic cycle of, “Oh my god, the world’s gone mad, what do I do, what do I do, what do I do, I’m fucking up again, I woke up late, I didn’t do enough, I just handled that the wrong way”—instead of being trapped in that self-conscious, self-hating prison, you sort of open up to yourself as you are. And I don’t want to say give yourself love, because that sounds like a little bit much. “Love? I don’t know that I deserve to give myself love.” You don’t need to celebrate, necessarily—it’s just space. I’m worthy, I deserve space. These are humble aims. But they change everything, I think. So it’s not a muscle that most people exercise very often, but if they did, it would really change the world, I think.

This is a drum I’m beating right now—compassion for the self. I used to be much more about, in the column even, find your people, fuck the people that don’t back you up and have your back. Having compassion for yourself includes, don’t torture yourself with the wrong kinds of people, especially in your twenties, when you’re just so prone to, “Oh my god, why do I feel so terrible all the time? Maybe it’s because everyone around me doesn’t make sense to me.” But so much of the start of finding your way in the world begins with resolving to treat yourself with care, and resolving to protect yourself, and just deciding, once and for all, that it’s less like, “I’m a princess and I deserve to be adored,” and it’s more like, “I deserve to respect myself, and consider my own feelings, and care for myself first in order to care for other people second. I don’t have to come last all the time to be a good person. I actually need to consider myself and give myself some space in order to put other people before me.”