Charlotte Rampling, 1973, nude, sits atop a wooden table at the Grand Hotel Nord-Pinus in Arles in the room in which matadors once dressed for battle. Legs ajar, wine in hand, body turned away, she squares her unsmiling eyes with the camera (and Helmut Newton behind it), as if to say: “This is not for you.”

To Sofia Coppola, this is what it means to be a woman. As a girl raised in Napa on a rambling ranch, her world-famous father travelling the planet, her mother alongside him,11“Why can’t we just be normal?” Sofia asked. this girl, the one who has always been defined by her style before anything else, considered fashion magazines her “link to the rest of the world.”22Vogue, 2003 She covered her walls in their images—mostly thin, mostly beautiful, mostly rich white women. The photo of Rampling came from a 1974 issue of Vogue. Sofia wrote about it for the magazine in 2003 and kept it into her 30s; deep into womanhood, she was still reminding herself who she wanted to be. Even today, more than a decade later—with six films behind her and two children in front—we still sense that photo watching over her, still sense her incipience. “Is she an eternal adolescent because she’s always primarily read as her father’s daughter?” asks Fiona Handyside, author of Sofia Coppola: A Cinema of Girlhood. If she is, her heroines come by it naturally. The Virgin Suicides, Lost in Translation, Marie Antoinette, Somewhere, The Bling Ring and her most recent film, the Cannes-lauded Beguiled, are all coming of age tales featuring young, privileged white women—pre-adolescents, actual adolescents, delayed adolescents—none of whom ever really come of age. To Coppola, the image of Rampling is, after all, just that, an image, the ideal that can never square with reality. “Girls are seen as really special and exciting and full of potential,” Handyside says of Sofia’s cinema, “womanhood is this thing that closes that down. So why would you want to grow up?”

*

To hear Eleanor Coppola tell it, her daughter was a typical adolescent who denigrated her mother and deified her friends. Sofia has said herself that she was “a little too cool to be a teenager,” that she wanted to grow up, felt more suited to adulthood. When she wasn’t traveling with her family, her youth was occasionally caught on film. In her first pubescent role—Tim Burton’s 1984 monochromatic short Frankenweenie—she is a gangly pseudo-teen credited as “Domino,”33She also used the pseudonym for her father’s film The Cotton Club that same year but has never explained why. who wears a long, blond obvious wig, a bow and a gingham dress—the platonic ideal of the American girl. She is also the only girl, a Dorothy type surrounded by munchkin boys, who exercises side by side with her Barbie doll (Barbie, naturally, being her one female friend). Two years later, 15-year-old Coppola acted through braces in Peggy Sue Got Married as the girl scout sister of Kathleen Turner. “Teenagers are weird and you’re the weirdest,” she says, her lackadaisical delivery already secured in place.

Around this time, according to her mother, Sofia became a fixture at her friends’ homes, claiming her own no “fun.” This teenage rebellion culminated in her flying off to Paris at 15 to intern at Chanel over two summers. “Every inch of her wants to break out of an ordinary routine,” Eleanor wrote in her diary. And she did. That same year, Sofia abruptly stopped being a teenager, though not of her own volition. Twelve days after her birthday, her oldest brother, Gian-Carlo (“Gio”), died unexpectedly at the age of 22 in a boating accident. “[W]hen my brother died, my teenage years got interrupted,” Sofia told The Hollywood Reporter. Later, when the family was organizing Gio’s things, Sofia slid into his white silk jacket. “It smells like him,” she said.

A little while after that a dude named Dave Markey became a sort of surrogate older brother to Sofia. Three years before he became known as the director of The Year Punk Broke, Markey was an underground filmmaker. When they met through mutual friends in the late '80s, Sofia was a fan of his low budget teen-girl-runaway-rock-band extravaganza Lovedolls Superstar, which featured early-days Sonic Youth. “She had already seen some of my work and was really into it so it was very flattering for me at the time,” says Markey, whose band stayed at the Coppola ranch. Sofia looked up to Markey, who was in his mid-20s, and he turned her onto “psychotropic cinema,” escorting her to Laemmle’s Monica Premiere Showcase (as it was then known) in Los Angeles to see Carnival of Souls. Herk Harvey’s only film, a goth-cult horror from 1962, is about a beautiful blond organist who exists in a sort of post-car-accident limbo—“I had no place in the world, no part of the life around me,” she says—and is drawn to an abandoned amusement park. “I remember that left a really big impression on her,” says Markey. “She was really blown away by that film.”

But several months later Sofia had no time for rep cinema. At that point, she was handed the biggest responsibility of her life so far: taking Winona Ryder’s place. Her father, Francis Ford Coppola, by then a well established New Hollywood force having helmed the mobstalgic Godfather franchise, had based the role of Mary—mafia alum Michael Corleone’s (Al Pacino) daughter—on Sofia. So when Ryder, who had already headlined several films, fell ill, Sofia was the obvious understudy, despite having never actually studied acting. In her first scene in The Godfather Part III, sitting in a pew with a scarf on her head, an enigmatic smile on her face, Sofia looks every drop the Virgin Mary. But internally she suffered from a severe case of impostor syndrome and overworked herself to the point of tears. Sofia knew she was not welcome. A Paramount executive disputed her casting, the other actors did too, and people advised Eleanor she was abusing her child. Mary folded under the pressure. In the film, Sofia’s delivery is flat, almost bored, her lines overlapping those of others, her weak presence only underscored by the power of Pacino’s. After Mary is fatally shot, she falls to her knees and says, “Dad?”44This is the second time Francis killed off his daughter on screen—the first was when she was gunned down as a street urchin in The Cotton Club. It ended up being a metaphor—she trusted her father and the critics killed her for it.

That same year, 1990, Sofia appeared in Markey’s music video for Sonic Youth’s “Mildred Pierce.” He shot her on Super 8 in front of Hollywood’s Max Factor building one afternoon after she designed her own costume and applied her own makeup—thick brows, black lips, Chanel—her exaggerated wide-eyed sneer reminiscent of Cry Baby’s Hatchet-Face. “I just had the concept to dress up Sofia as Joan Crawford in Mommie Dearest,” Markey says. “So she’s actually channelling Faye Dunaway.” Around that time Sofia also befriended Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon, whose fashion label, X-Girl, she would soon join. “Kim inspired me because she tried all the things that interested her,” she told Elle. “She just did what she was into.” As for herself, Sofia wasn’t sure what she was into. It was an embarrassment of riches. Fashion, maybe? She was in charge of the outfits on a film called The Spirit of ‘7655She had previously designed the Chanel jr. costumes for “Life Without Zoe,” her father’s maligned Eloise-like segment in the 1989 film New York Stories, which Sofia also helped write. and at one point considered studying costume design. “She was really into that,” says Markey. But a year later Sofia was onto a third college and other interests. “I want to take photography and painting and learn more skills,” she told her mother. So she studied art history and co-founded a clothing company, Milk Fed, in Japan. “I became a dilettante,” she told The New York Times. “I wanted to do something creative, but I didn’t know what it would be.”

Sofia’s Beguiled excises the shrewdest character in Cullinan’s story—the school’s slave, Mattie (played arrestingly by blues singer Mae Mercer as Hallie in the 1971 adaptation)—with the film’s only nod to the Civil War’s racial foundation reduced to “the slaves left.” Coppola has said in several interviews that her focus was specifically on the power dynamics between men and women. She told The Hollywood Reporter that she wrote Mattie out, “because I didn’t want to treat that subject lightly,” adding more recently to BuzzFeed that Mattie’s was “a really interesting story, but it’s a whole other story.”9

99“I would love to have a more racially diverse cast whenever I can,” Sofia told the site. “It didn’t work for this story, but of course I’m very open to stories about many different experiences and points of view.” Presumably that is also why she turned the book’s biracial teacher, Edwina, into Kirsten Dunst. But Edwina’s whitewashing is particularly puzzling considering her background would have been perfectly positioned within Coppola's oeuvre-wide theme of identity. In Cullinan’s novel, Mattie surmises that the reason Edwina is so isolated from the rest of the school is “because she don’t know who she is—she don’t know what she is.” In the film, we are meant to believe that it is simply Edwina’s oppressive timidity that has separated her from the faces that look exactly like hers. But you can’t help hearing the strains of Beyonce’s “Sorry” when you see Fanning on Instagram recreating a scene from Lemonade—The Beguiled shot on the same Louisiana plantation1010“I didn’t see Lemonade, but I saw the chair and it was explained to me,” Sofia told The Los Angeles Times.—casting herself as Beyonce and Dunst as Serena Williams, both of these white actresses clothed in antebellum cotton.

*

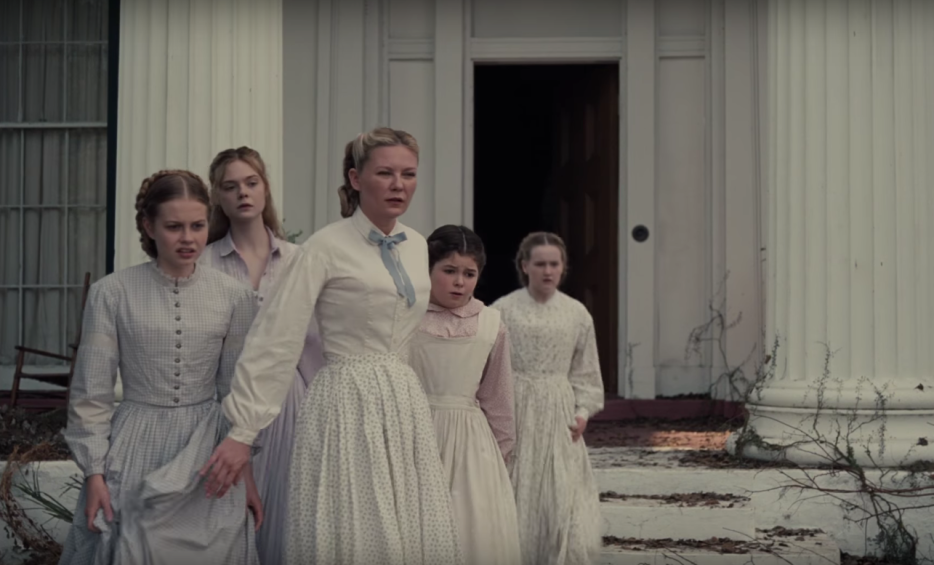

Sofia Coppola, 2017, sits on a winding staircase surrounded by femininity, pre-pubescent to middle aged. Drenched in light, dressed in pale ruffled ankle-length frocks, frozen in place, the seven girls and women around her gaze out from their cramped quarters with various conflicting expressions. The director, 45, is in the middle, white shirt, black pants, white runners, androgynous, the contemporary center of control around which all these females orbit.

Coppola is as quiet in this photo as she is in real life. She is so soft spoken that her mother regularly had to strain to hear her when she was a teenager. And when her father commanded her to speak up on set, she did not. Neither do her heroines. Even Marie Antoinette, as loud as she is in dress, often holds up a fan to obscure her mouth. “There’s a sense in which they are saying, ‘You know what? You don’t have to shout,’” says Handyside. Sofia pushes silence, privileging imagery over dialogue, her scripts sparse, her visuals abundant. When I interviewed her at the end of 2010, her sentences would trail off, dissipating into the ether, often unsatisfying—too brief, too superficial. I described her then as “disconnected,” and there continues to be a sense that she keeps herself disengaged from the world (even outside the media). “I think it’s a survival strategy,” says Handyside. “I think sometimes she gives people enough rope to hang themselves with just by not responding.”

It is also a way of performing femininity. Coppola will play the submissive, placating her male actors in particular, but inevitably obtaining from them what she wants, sometimes to the point of objectification. “It’s just like my fantasy to get him to sit there and dress him exactly how I want him to be and do everything just exactly how I want,” she said of Bill Murray on the set of Lost in Translation (he nicknamed her The Velvet Hammer). She quietly inverts the male gaze, in Lost turning John Kacere’s painted portrait of a woman’s rear into a moving image that barely moves, laying it across the screen a spell too long, prompting us to question our own gaze. In Somewhere a bed-sprawled Johnny Marco is surrounded by naked gyrating women but sees none of them. In The Virgin Suicides, a muscular demigod floats in a pool of electric blue, in The Bling Ring it is the un-sculpted boy who is self conscious. In The Beguiled too, we see McBurney’s body—caressed by the light, like a Roman statue—immobile, entirely under the power of the women around him.1111“Colin was a really good sport about being our token male,” Sofia told Vanity Fair. “He knew that he was the object.“

Like so many of her heroines, Sofia Coppola seduces to control. She learned this, no doubt, being surrounded by men—father, brothers, cousins—ensconced in an industry guided by their sex. She says she was indulged growing up but it was an indulgence stemming from a stereotypical notion of femininity. Her father, his physical presence almost as overbearing as his psychological girth, is ubiquitous in behind-the-scenes footage of her first three films, manspreading on set, making suggestions even after his daughter has already secured an Oscar. Even filmmaker Wes Anderson, an old friend of Sofia’s, told The New York Times, “You want to look out for her. She turns everyone into her big brother.” Of the more than 20 people I contacted about Sofia Coppola, less than a handful agreed to speak with me. In the wake of The Godfather Part III, this is how she likes it. This is her own story, why would she not want to direct it?

Her own story, the way she tells it, repeatedly returns to adolescence, those years which were abruptly taken from her, which she continuously reclaims on screen. To Coppola, womanhood is imprisonment, girlhood is freedom, and her feminism lies in her refusal to compromise the latter. She will not, for instance, adopt the “feminist” label, despite her constant devotion— albeit a devotion that is blind to intersectionality—to female identity. When she became the second woman in the history of Cannes to win best director for The Beguiled (a film with a set in which, according to Variety, women outnumbered men), she thanked another feminist icon, Jane Campion, the only woman to win the Palme d’Or, for “being a role model and supporting women filmmakers.” But her inspiration was Jo Ann Callis, specifically her 1977 image “Woman with Blue Bow.” The photo shows an angelic blond with curly hair, her head thrown back, only her neck and nose visible. Around her throat sits an aquamarine satin bow which connects to her lacy white strapless dress. Look closer and it seems the ribbon is forming a groove in her neck, as though it is a fraction too tight. Behind her is water coloured wallpaper of blue leaves, three golden birds flying around her as though she is some kind of S&M Cinderella. “It reminded me of the feeling of femininity and frustration I wanted to achieve in The Beguiled,” Sofia said.

“Nous sommes des filles”—“We are girls”—say the students in the film as they conjugate the French verb but do little more to project their gender. Sofia chose to re-adapt The Beguiled in order to express “the women’s point of view,” but the story does not really change. The women remain pale specters cut off from the dark war raging outside. In their decrepit estate they have become arrested in time with only McBurney to remind them of the outside world, one which promises excitement, but also brutality. To preserve their innocence, they must destroy this man, though in so doing they destroy their own prospects. Like a caged beast, McBurney trashes his bedroom after losing his leg at the hands of the women. In protest, he screams, “I’m not even a man anymore!” but it is a mere storm in a teacup, the same one that brews inside these women. To little effect. The film ends where it starts, with a girl searching for sustenance, with the women dragging a man in and then out of their coven. Sofia’s heroines have tried to get out and tried to get in, but this is the first time they simply choose to stay put, a sort of cynical acceptance of their lot. The last scene of The Beguiled shows the body of McBurney outside the closed gates, behind which the women watch from the steps of their crumbling institution, ashen and still, in a sense as dead as he is; yet, even then, nowhere near as free.