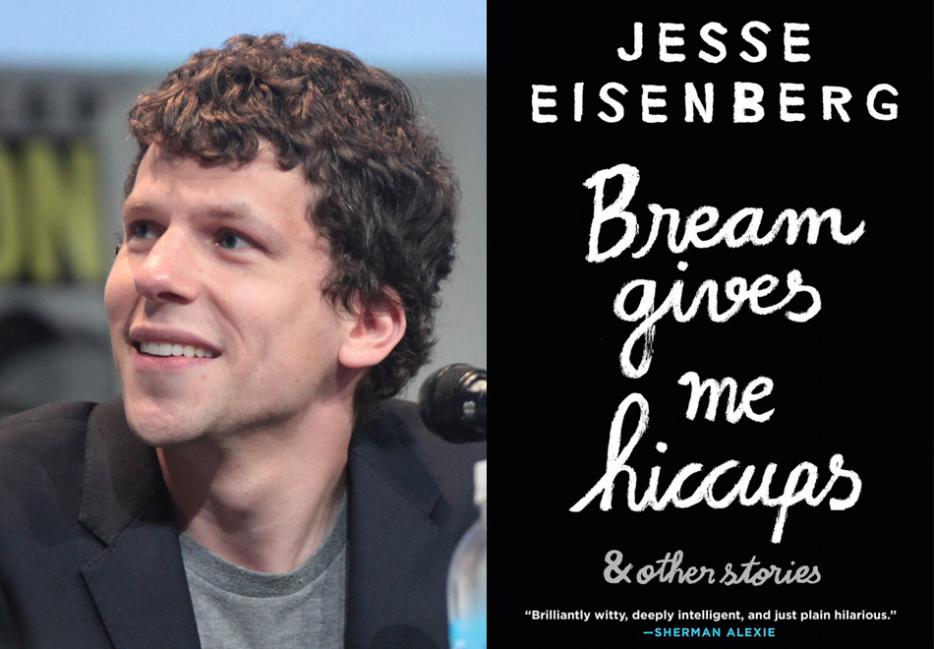

Jesse Eisenberg has starred in 36 movies, acted in six plays, written three, and voiced (in his estimation) “five or seven books on tape."11“Exclusively Young Adult,” he says, “I don’t know why. My best friend’s a teacher in Brooklyn, so in her case they listen to them, and then I go in and read to the kids in the voice that I use for the books, which is my voice.” And now he’s written one book, Bream Gives Me Hiccups, a collection of humorous short fiction published by Penguin Random House this past fall. The title story, structured as a series of restaurant reviews written by a nine-year-old boy, rivals The Curious Incident of the Dog In Nighttime in terms of its emotional heft.

He’s a busy guy. To reach him I call the landline of his Great Aunt Doris, who will be turning 104 this February. She’s given permission for us to talk during one of his weekly visits while she eats her applesauce.

*

So you visit Doris every week?

Since I was seventeen. I used to go every Thursday but my schedule is so erratic that I now go whenever I possibly can.

Has she read your book [Bream Gives Me Hiccups]?

I’ve told her about it but no—no, she doesn’t have the patience.

Does she follow your work in general?

I mean, yes, but only from what people tell her. [Laughs]

You sound relieved.

She has been a wonderful sort of refuge for me. I’m in an industry where people irrationally laud people who don’t do much work, and she’s from a generation that thinks my productivity is lazy.

In what sense?

[Laughs] Uh … Okay, so:

‘Why didn’t you write anything today?” …

“Oh, if you’re an actor, why are you not acting in anything right now?”

I say, “Well all the stuff they sent me was stupid.”

She goes, “What do you mean it’s stupid?”

And I say, you know, “It’s cliché, trite characters—there’s nothing really to dig into.”

She goes, “So you’re just going to sit at home?”

“Well, I’m going to wait for something good to come along”—and to her, that doesn’t make any sense. I mean could you imagine any other civilization or world where someone would just sit at home waiting for something better to come along? No, you go and live things.

What did she do for a living?

She worked in business, forever. She was a bookkeeper for the same man for seventy years. And she walked to work every day. And she worked up until she was ninety-three—for the same guy. She only stopped working when he died.

And she’s in Manhattan?

Yeah, I bike up here [from Brooklyn] and before I got a CitiBike membership, she would insist that I take the bike inside, which I never did because I know that if she saw it inside her house and on her carpeting she would be disgusted. But she was convinced it would get stolen outside.

I've had several bikes stolen, but never outside her house. She lives in Murray Hill and at 103, she's the median age, so there are not a lot of bikes, or bike thieves.

You grew up in New York City, for a while, right?

We lived in Queens until I was five and then New Jersey. New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Do you remember Queens?

It’s just east of Manhattan.

Okay, come on.

I grew up in Bayside, which is nominally inaccurate.

So, pretty suburban, in general.

Queens? —No, it was urban, it just wasn’t by the bay, and so that’s why it’s nominally inaccurate—oh! Sorry. In New Jersey—yes. It was suburban. I had a suburban upbringing.

Me too. Were you bored?

Yes—no, I was miserable. I was absolutely miserable. Not because it was bad. Just because it was bad for me. I’m sure it was great for other people. Most people. Most people in the suburbs…

You write a lot about Manhattan—urban places. Is that because you can’t bring yourself to revisit the suburbs?

My last play [The Spoils] was about a guy who grew up in the suburbs and was coming to terms with a weird suburban past that he’d hidden. So I don’t avoid [having grown up there]. I just think in humor writing the suburbs are more difficult to characterize. They’re slower-paced. The people aren’t as neurotic. It’s easier to find those people in New York—and it’s easier to make fun of people who are, well, frankly, rich.

If you’re living in an urban society like Manhattan, chances are you’re rich, and your struggles are based on the uncomfortable interactions you have with other rich people—struggles of luxury. They’re status struggles. In the suburbs struggles are more real, and therefore they’re less funny.

In “Bream Gives Me Hiccups,” the narrator reviews restaurants that he goes to with his mother in Manhattan. What places would he have reviewed in New Jersey?

Well, where I grew up, we went to two places: we went to Chi-Chi's, which was a Mexican restaurant, and we went to Denny’s, which was not a Mexican restaurant. And Chi-Chi's was the place we went for birthdays and Denny’s was the place we went when my grandparents came to visit. And those were the two holidays: birthdays and visits.

When I was young, I think somebody told me that “Chi-Chis” means breasts, and then I used to go, I was mortified that I was eating at a place called “Breasts” on my birthday. So, not only the mortification of having a birthday and having attention paid to you in a disproportionate way, but also eating at a place named after breasts, which is something I hadn’t yet come to terms with.

Is that what it means?

I don’t know.22Writers note: a Google search for: “chichi spanish to english” later revealed that “Chichi” means “fanny” in the United Kingdom, “beaver” in the United States and “tit” in Mexico. Further investigation showed that the Chi-Chi's restaurant chain went bankrupt in 2004, following what one site calls “one of the worst hepatitis A outbreaks in American restaurant history in November 2003 at a Chi-Chi’s in the Pittsburgh area.” “Four died, and 660 others contracted the illness eventually traced to green onions at the Chi-Chi’s at Beaver Valley Mall in Monaca, Pa.” Conclusion: Never go to Chi-Chi's. You can't. It would be strange that they’d name a suburban restaurant place—

But that would be the perfect place to hide it—you know, to hide like, a joke like that.

Yeah, no one would know.

It’s like giving the reverend or whatever he is in The Little Mermaid a boner. Like, you have to have fun where you can.

You think that really was … not his knee?

I talked to an animator about it once and he said it was definitely intentional.

Oh my god. I can’t believe they can get away with that.

I don’t think it looks like a boner. But it’s like a small shift that apparently they would have had to do intentionally.

Wow, fascinating. That’s so interesting.

You know what’s funny is growing up I used to eat at a restaurant called Boners.

No.

No, I didn’t. I’m just kidding.

Hello?

[Ten minutes later]

Sorry, the cordless died. Hopefully it’s the only thing here that does.

Are you the only one there with Doris?

I always visit her alone.

What’s the typical visit like?

After an update on Hillary Clinton's campaign, we discuss personal matters for a few hours. Then she tells me to stand up straight and I leave.

I play cards sometimes with my—

We don't play cards or do anything that's fun.

Oh.

[General silence]

Is she small?

Who?

It’s just my husband’s great aunt is Doris’s age, and she’s very small. I think she started adulthood a little taller than five feet, but now she reaches only to my elbow. Is Doris shrinking?

She is. But her personality looms large.

So, I feel like your short humor pieces are all love stories—high stakes, too, because often there’s a lot to overcome, character-wise. For instance, in “Bream Gives Me Hiccups,” the mom can be mean and biting toward the narrator, and in general she’s kind of a drunk homophobe.

I tried to push that as far as I could go—having a character that really says the worst possible things and seems like the worst mother on earth.

I mean, “liking” is sort of the simplest goal. But if you can come to the point of understanding and sympathizing with a character, it’s that much more engaging, and that much more of an accomplishment for the story, because you’ve kind of asked for the impossible.

How do you go about finding the knowable parts of an unlikable character?

By virtue of having a background as an actor you’re required to sympathize with even the worst characters. I like playing characters that are troubled or even cruel because you have to find something sympathetic or understandable or even benevolent in the context of an otherwise horrible person. The trick is to think of someone from the inside out rather than the outside in. So if someone appears violent, you try to come up with a series of reasons for why.

In The Social Network, Zuckerberg wasn’t written as likable, but you made him lovable. How did you do it?

In that movie, the character appears vengeful or self-centered, but I had to think that he was defending his child, which let’s say in that case is a website. But if someone is defending a child, all of their actions, regardless of their actions, are justified.

So, in the case of the mom [in “Bream Gives Me Hiccups”], she thinks she’s been fucked over with this divorce. That’s her justification.

I hadn’t thought of that, but yes. If you feel like you’ve been cosmically jilted then anything you say or do is justifiable, because you’re powerless. She feels like she’s been cosmically jilted because she’s a woman who’s been left, which isn’t uncommon and is horrible in a society where men have disproportionate power. In business, too: she hasn’t had a job. And therefore everything she says and does is justifiable because she’s totally powerless.

I imagine when her life was going well and she was married and had a lot of money by virtue of her husband having money, she would never say anything horrible, because she had to be on, so to speak. She was representing an important group. But now she’s powerless, and when you’re powerless your anger goes into a vacuum. You can say all the things you’ve been harboring.

I love every part in the story where she orders dessert and talks about how she’s earned it.

[Laughs]

What is that about adults? We say stuff like “UGH, it’s so rich,” or “No, no, I shouldn’t,” with this terrible gleam in our eye. I’ve never seen anyone so excited and conflicted as an adult presented with dessert at a restaurant.

I remember living in New York City after high school and realizing I could get a cookie whenever I wanted. It could be 4 p.m. and I could get a cookie if I wanted to, and I didn’t, usually, but the thought made me very excited.

There’s another great, really moving moment where the nine-year-old protagonist is empathizing with the social pressures faced by dinosaurs. You write:

“The one who was the nicest was the Apatosaurus because he was really big but he had a tiny little head and he never ate any other dinosaurs. And I thought it must have been scary to be an Apatosaurus because he just wanted to be nice but there was probably a lot of pressure to be mean because he was a dinosaur.”

That’s such a beautiful, universal statement. Does it hit home for you at all in terms of what you were saying before about Doris and the vacuum of the film industry—like, how might it apply to Hollywood in particular?

I hadn’t ever thought about it, but of course [it’s personal], because you feel like—yeah, it’s strange—I think a lot people in the entertainment industry, especially in popular culture entertainment, feel pressure to be a little more cutting than they naturally would be. For a lot of people in the arts, you initially get interested in the arts because it allows you to express yourself, it allows you to maybe have an emotional catharsis, and then it gets kind of commodified by people who are interested only in what is only, let’s say, financially viable from it—and you end up, maybe, getting tempted into, I don’t know, certain feelings, that you would otherwise detest or avoid.

And yeah, I suppose I felt that way. You know, you do something very personal, and then a year later you’re looking at the box office receipts and are feeling either buoyed by them, or disappointed by them, but placing value on them nonetheless. And I think your A Year Ago Self—the one that was making the personal thing, or doing the personal thing, or writing a personal play, or acting in a personal movie—would be very disappointed.

Speaking of commodification, Amazon just optioned your book!

[Laughs]

Did it come naturally to adapt it [for the pilot]?

I spent three years trying to do it. The kid writes a series of restaurant reviews but they don’t actually exist in the world. So I had to figure out a way that he could still write restaurant reviews, which meant figuring out how he could be writing that, and flashing back, and flashing forward. I have a sense of what actors like to do, so I also wanted to write a role for an actress [his mother] that wasn’t just a foil to a comedic foil.

That relationship—an overbearing mom, a beleaguered, neurotic boy—it repeats itself throughout your stories.

My parents are married and have a stable relationship, but I guess I, in a way, envied struggle, I guess out of guilt. So maybe I try to write about broken families or emotionally distant parents, so I can feel like I don’t have something better than a lot of people.

Growing up, your mom worked as a birthday clown, right?

Yes, my mom was birthday party clown until I was about twelve. She was self-taught. She came out of the socialist hippie movement. So the taglines of her games was you have to lose to win, which was a direct line of Marx.

Did she ever birthday clown (is that a verb?) any of your parties?

No, she never did my parties; she said that was like a conflict of interest. So she bartered with the local magician, who did my birthday parties, in exchange for her doing parties for his friends.

So, I had this great magician do my birthday parties for free, and I always thought he was an older man—turns out he was like, 16 at the time.

[Laughs]

I found out he fell down a flight of stairs a few years ago and died.

[General silence]

That’s not a bit?

No! I guess it almost seems like one.

That’s terrible, I’m so sorry. I only asked whether it was a joke because I realized recently that I’ve been taking comedy writers seriously when they’ve been doing bits around me.

Oh, oh.

Like, I ask all these earnest questions while they’re telling me a story about how so-and-so fucked someone without a condom and is so angry about it and I’m like, “Oh my God, are they okay, I don’t understand?” And then someone will nudge me and be like, “That was a bit,” and I’ll feel really stupid.

Well, bits should be funny as well. That sounds like more of a lie than a bit.

Yeah—actually, a friend’s kid asked me this the other day: “How do you tell the difference between a lie and a story?”

Well, a story has to be entertaining in some way, and a lie is just misleading.

I wish you’d been there to explain.

A lie is for some selfish reason and a story is for some benevolent one.

Is your mom still a clown?

No, she went back to school and now teaches compassion in medicine.

That’s so noble.

I know.

When you come up with an idea for a story, at what point do you know whether it’s going to be a short story or a play?

I feel unqualified to answer this. But I guess things seem pretty clear to me at the outset. If there’s a pretty funny, high concept idea that would make for a thousand word humor piece, chances are that same thing would not work for a scenario where three where people are emoting onstage for three hours. And conversely, by way of better example, something that works as a sixty page novella and involves character development …

[A small cry on Jesse’s end, in the background]

Hold on, one second, I have to call you back—[to Doris] yes! Hello! Hello!

*

[One hour later]

Hi! Is Doris okay?

Sorry, I should have called to say, “My aunt’s not dead.”

She just sort of fell—

I thought she was eating applesauce—

—and then she was pissed at me for being on the phone so—

She fell eating applesauce?

It was just a sort of keel. She was eating applesauce and keeled forward very slowly until her face was on the table. And then I guess she decided to take a nap, and after sleeping for a while she called out, “Jesse, I’m uncomfortable.”

Is she okay?

Yeah, yeah! Sometimes it’s a big deal and sometimes it’s not and this time it wasn’t. She’s asleep on the couch now.

I’m going to let you go. But can I say one more thing about your book?

It’s fine—she’s fine. I’m walking now, actually. The night nurse comes at seven.

Oh, all right. I’m so glad Doris is okay! I was worried—also, I emailed you about Chi-Chi’s.33See previous footnote.

Does it mean “Breasts”?

Well, yes, but also the food was poisonous. So you’re really lucky.

Anyway, you’re just so great at dramatic irony—that part in [“Bream Gives Me Hiccups”] where the narrator and his friend run into an Internet predator without knowing it. It’s a very high stakes moment for the reader, because we know but they don’t, but for the narrator, it’s this simple moment where he’s just feeling very close to his friend, and a man happens to be getting arrested in the parking lot.

That’s why a nine-year-old boy is a good narrator. He can be hyper-aware of the hypocrisies in the adult world, and also totally naïve to hidden meaning that adults would be able to pick up on. It’s that innocence and insight that children have.

In that moment, he’s sitting there with Matthew waiting for Matthew’s Internet friend, and he’s feeling a mix of jealousy about that friend, and love for Matthew’s even though Matthew makes weird mouth noises. And he has this great conclusion that I love:

He goes, “It’s easy to like someone on the Internet. When you’re with someone in person you have to see all of their weird things.”

Yeah, Internet versions of people are like the edited highlight reels of them—their best pictures from the best angles—and when you’re with somebody in person, you have to confront all the odd parts of them—the smells, the bad angles of their face—and that’s healthy. We should experience all the parts of the people we’re living with, because it’s real, and the Internet edits all that out very cleanly.

Is that why you’re not on social media?

Well, it probably has less to do with my aversion to that stuff and more to do with the fact that I am already a very public person. I think if I had no public outlet and I was not in the public eye, I would be very interested in having a Twitter account because it’s a fun way to express your thoughts to a lot of people. But I do interviews like this one. And then movies where people not only scrutinize me but scrutinize the most personal parts of me—not only my acting job but my face, and my behavior and my mannerisms. So I have an aversion to putting anything else out about myself. As a result of my profession, I try to keep the rest of me private—which I know seems hypocritical. But I guess you have to draw your own line between what is for you public versus private.

Do you ever get used to that kind of scrutiny? (People talking about your face?)

You know, I don’t get used to it, but I feel—no—but the more I enjoy what I do (and I increasingly do) the more I worry less, the more I’m governed less by the public reaction to it—because if you like what you do, then that’s really the thing that matters most.

Did you enjoy writing this book?

Oh yes—well, I loved every part of it. Otherwise I had no incentive to do it.