By the time I signed up for Ashley Madison in 2003, I had spiraled into a deep depression. I had recently hurt some people with my callousness and selfishness—first a woman with whom I was involved, then some friends—and with the image of myself as a good person shattered, I slid into a pit of self-destruction. I cut myself off from the world: slept all day, played video games all night, lost a quarter of my body weight.

I don't think it registered to me at the time that Ashley Madison was supposed to be a site people visited to cheat. It just seemed salacious—enough of a promise that something there could explode my crumbling life. I put up a photo of my newly skinny self and got two responses, both of which came in the form of photos of improbably attractive women, naked, either bent over or with legs spread apart. I was too naive then to know that they were almost certainly sent by bots or men trying to mess with me. I didn't respond anyway. I might have been, in many ways, a different person then, but in other significant ways, I was very much the same.

*

The Ashley Madison leak has become a stark example of how privacy online is far more fraught and complex than most realized or wanted to believe, to make no mention of the swirl of questions raised around cheating, monogamy, hacking, and publicizing information. Yet, we also now have a sense that Ashley Madison itself was essentially a years-long grift. Based on data from the hack, it seems likely that only a hair over zero percent of the messages sent on the site were from women. Given that it never really billed itself as a site for men seeking men, it’s unlikely to have facilitated much actual interaction at all, let alone illicit romance. It was, in essence, a site dedicated to fantasy.

But in publicizing all that yearning for fantasy—the names of those who searched for an unknown something in vain—the leak has nonetheless forced people to comb back through their pasts and past transgressions. It is an effect of how the web and digitality often collapse the distance between past and present: The archive of who we are in the collection of tweets, status updates, blog posts, and photographs scattered online looms like some peat bog of personality, always about to gurgle up some perfectly preserved act from our personal history.

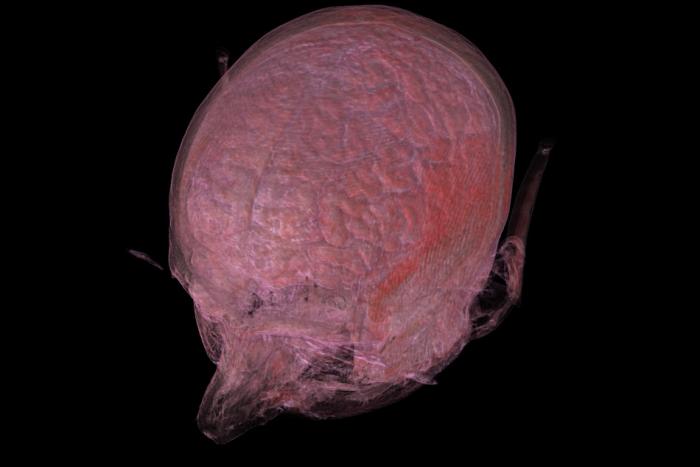

The digitally inflected individual is often not quite an individual, not quite alone. Our past selves seem to be suspended around us like ghostly, shimmering holograms, versions of who we were lingering like memories made manifest in digital, diaphanous bodies. For me, many of those past selves are people I would like to put behind me—that same person who idly signed up for Ashley Madison is someone who hurt others by being careless and self-involved. Now, over a decade on, I'm left wondering to what extent that avatar of my past still stands for or defines me—of the statute of limitations on past wrongs. Though we've always been an accumulation of our past acts, now that digital can splay out our many, often contradictory selves in such an obvious fashion, judging who we are has become more fraught and complicated than ever. How, I wonder, do we ethically evaluate ourselves when the conflation of past and present has made things so murky?

*

Sometimes, I aimlessly trawl through old and present email accounts, and it turns out I am often inadvertently mining for awfulness. In one instance—in a Hotmail account I named after my love for The Simpsons—I find myself angrily and thoughtlessly shoving off a woman's renewed affection because I am, I tell her, "sick of this." I reassure myself that I am not that person anymore—that I now have the awareness and the humility to not react that way. Most days, looking at how I've grown since then, I almost believe this is true.

Yet, to be human is to constantly make mistakes and, as a result, we often hurt others, if not through our acts then certainly our inaction. There is for each of us, if we are honest, a steady stream of things we could have done differently or better: could have stopped to offer a hand; could have asked why that person on the subway was crying; could have been kinder, better, could have taken that leap. But, we say, we are only who we are.

We joke about the horror of having our Google searches publicized, or our Twitter DMs revealed, but in truth, we know the mere existence of such a digital database makes it likely that something will emerge from the murky space in which digital functions as a canvas for our fantasies or guilt.

That is how we justify ourselves. Our sense of who we are is subject to a kind of recency bias, and a confirmation bias, too—a selection of memories from the recent past that conform to the fantasy of the self as we wish it to be. Yet the slow accretion of selective acts that forms our self-image is also largely an illusion—a convenient curation of happenings that flatters our ego, our desire to believe we are slowly getting better. As it turns out, grace and forgiveness aren't the purview of some supernatural being, but temporality—the simple erasure of thought and feeling that comes from the forward passage of time.

*

The digital archive of the self makes that smoothing effect of time harder to maintain. Those confounded "Memories" or "Flashback" functions in services such as Facebook or Dropbox vomit up images and words from the past at inopportune times—some picture of another ghost to whom you could have been kinder. Meanwhile, Google and Twitter searches dredge up unwanted shards of the self—whether by you or, worse, others with ill intent. If the passing of the years slowly sands down those splinters of cruelty and embarrassment, the digital self as a collection of floating holograms pushes them up again, past selves puncturing through the veneer of a coherent identity to reveal not just our own wounds, but the injuries we have inflicted on others.

If, however, it was once easier to maintain a self through the suppression of what we wished not to remember, the Ashley Madison hack reminds us that, eventually, some secrets will spill out. We joke about the horror of having our Google searches publicized, or our Twitter DMs revealed, but in truth, we know the mere existence of such a digital database makes it likely that something will emerge from the murky space in which digital functions as a canvas for our fantasies or guilt. Collapsed into the same experiential space, the past and present colliding, our digital selves are archives of our identities. This is the holographic self—not a timeline of identity, or a steady accumulation of wisdom, but the criss-crossed network of being a person, mapped out onto screens. To be a digital human is to be many, and in more than one place at once. Am I a good person? Depends on where on the timeless web of self you stand in order to look and judge.

*

If digital collapses the y-axis of time on the graph of identity, squeezing the past and present into an uncomfortable closeness, then it also expands the spatial x-axis outward. Instead of a single self existing in one place, we have an identity spinning out into a number of different sites. We express various aspects of ourselves in different locations, putting fractured facets of our identity on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and elsewhere. We curate and perform, it's true, but we often revel in the distance between not only our bodily self and online personas, but between those personas, too—solemn posts on Facebook and thirst traps on Instagram.

Splitting out parts of the self in this way can be done for a variety of reasons, but often it’s to control or supersede some particular aspect of the self. What we once did with time, letting parts of who we are recede into the enveloping dark of the past, we now do with digital, scattering seeds of experience across a range of places to gain mastery over them—to gain mastery over our sense of self.

Yet, I am reminded of Julius, the protagonist in Teju Cole's novel Open City. In that ambulatory text, Julius mostly wanders around New York City engaged in introspection, strolling past sites of historical trauma. Near the end of the novel, though, Cole reveals that Julius himself has inflicted trauma on another person—a revelation the text responds to by continuing in its ambivalent, sympathetic wandering. If throughout most of the novel's see-sawing between past and present Julius is a collection of holograms—aspects of his self that merge into some virtual amalgam—he uses that scattered detachment to distance himself from his crime. It is deeply unsettling—a kind of metaphorical warning of how the holographic self can be deployed to evade ethics and consequence. Past and present may merge, but multiple selves allow us to compartmentalize our acts.

I wonder how many other men, despite having been duped, are now attempting to compartmentalize their own past actions on Ashley Madison—of how, now faced with the past, they are attempting, both honestly and not, to say that they are no longer those people who sought solace or fantasy in the arms of people who weren’t there. Yet, strangely, even in the face of the melancholy emptiness of the Ashley Madison leak, we all are faced with the abstract possibility of that reckoning: not just in the text and images of the web, but in the systems of surveillance on the streets, in the symbiotic, mutually constitutive relationship between databases and hackers, the link between a secure archive and, inevitably, its easily searchable public mirror. Our fantasies may yet be made public.

What will we then make of the breezy, binary moralizing that accompanied the Ashley Madison hack—the kind that says those who have to confront their shadows deserve whatever they get? When we are all holographic—all a set of competing avatars meant to obscure that our digitized selves are always our past, present, and future—will we then also say that we are always to be judged as just one person, one accumulation of things?

It’s as if in our righteous moral judgment, what we are expressing is not a sentence, but a desire to fix what is actually always in flux.

The line between evasiveness and forgiveness, cowardice and grace, is thin, often difficult to locate, but absolutely vital. It seems, though, that our ethical structures may slowly be slipping out of step with our subjectivities. If we have abandoned the clean but totalitarian simplicity of Kant’s categorical imperative, instead embracing that postmodern cliché of a fluid morality, we still cling to the idea that the self being morally judged is a singular ethical entity, either good or bad. It's common on social media, for example, for someone to be dismissed permanently for one transgression—some comedian or actor who is good at race but bad at gender (or vice versa) to be moved from the accepted pile to the trash heap. If our concept of morality is fluid, our idea of moral judgment is not similarly so.

That notion of self assumes morality is accretive and cumulative: that we can get better over time, but nevertheless remain a sum of the things we’ve done. Obviously, for the Bill Cosbys or Jian Ghomeshis or Jared Fogles of the world, this is fine. In those cases, it is the repetition of heinous, predatory behaviour over time that makes forgiveness almost impossible—the fact that there is no distance between past and present is precisely the point. For most of us, though, that simple idea of identity assumes that selves are singular, totalized things, coherent entities with neat boundaries and linear histories that arrived here in the present as complete. Even if that ever were true, what digitality helps lay bare is that who we are is actually a multiplicity, a conglomeration of acts, often contradictory, that slips backward and forward and sideways through time incessantly.

Some obvious things—rape, murder, abuse, pedophilia—are unforgivable. About most of the mistakes and transgressions that make us who we are, however, I am less sure—uncertain of not only what is right and what is wrong, but that being human can ever be pinned down so neatly. It’s as if in our righteous moral judgment, what we are expressing is not a sentence, but a desire to fix what is actually always in flux.

*

People are deleting their tweets. As The Awl’s John Hermann puts it, Time is a Privacy Setting. To obscure the past self and the contexts that produced it is a way to suppress the difficulty that comes from appearing to be more than one person.

It makes sense. Recently, a Canadian political candidate, Ala Buzreba, was forced to bow out of the federal election race because of tweets she wrote four years ago when she was 17. Particularly as someone in the public eye, the past self that bubbled up was taken as a reflection of her current self, despite the fact that there were many reasons not to: age, the developmental importance of one’s early twenties, or the simple fact that people change.

One might say, “oh, it’s just politics,” and one would be right. Politics is often where deeply rooted bias spills out. We may talk of forgiveness and fluidity, but the pressure, circularity, and scrutiny of political races is like a distilling process for deep-seeded ideology. We may claim looks don't matter, but when taller political candidates consistently win nominations and elections, we know that isn't exactly true. In the case of Ala Buzreba, a strong idea of the relation between personal history and current identity was revealed.

This is no small matter, one in which we might easily say, “listen, we all contain multitudes, let’s just cut everyone a little slack.” The consistency of self is at the core of our idea of ethics or justice. Even to think of extreme, obvious examples—Nazi war criminals in hiding, say—already reveals that the notion that our past selves are not our current selves is altogether too glib a reaction, too simplistic to actually grapple with the difficulty of how we apply rightness to correct past wrongs.

But in something as comparatively innocuous as the Ashley Madison hack, it bears remembering that few people, if any, were actually cheating. Instead, they were all—well, I suppose we were all—performing fantasy, projecting a vision of a potential future self onto a digital canvas in order to toy with it: to let that image sit in the light and be allowed to work its cathartic effect even though it wasn’t real.

The terror of the personal, digital archive is not that it reveals some awful act from the past, some old self that no longer stands for us, but that it reminds us that who we are is in fact a repetition, a cycle, a circular relation of multiple selves to multiple injuries.

Acts that hurt, acts that have material and emotional consequence, cannot be so easily erased by the idea of a multiple self. Yet, the strange thing about the Ashley Madison hack is that in formalizing the search for fantasy—in making a digital record of desire—we have produced a database of the self, and like all databases, it may one day be exposed. Perhaps, then, the effect of digitality on identity is less about the plurality of self than it is the materialization of the subconscious—the fact that our inner desires not only have a place in which they can be expressed and explored, but have a record of such as well.

Is the difficulty of digitality for our ethics, then, not the multiplicity of the person judged, but our Janus-faced relation to the icebergs of our psyches—the fact that our various avatars are actually interfaces for our subconscious, exploratory mechanisms for what we cannot admit to others or ourselves?

Freud said that we endlessly repeat past hurts, forever re-enacting the same patterns in a futile attempt to patch the un-healable wound. This, more than anything, is the terror of the personal, digital archive: not that it reveals some awful act from the past, some old self that no longer stands for us, but that it reminds us that who we are is in fact a repetition, a cycle, a circular relation of multiple selves to multiple injuries. It’s the self as a bundle of trauma, forever acting out the same tropes in the hopes that we might one day change.

What I would like to tell you is that I am a better man now than when, years ago, I tried my best to hide from the world and myself. In many ways that is true. Yet, all those years ago, what dragged me out of my depressive spiral was meeting someone—a beautiful, kind, warm person with whom, a decade later, I would repeat similar mistakes. I was callous again: took her for granted, pushed her away when I wanted to, and couldn’t take responsibility for either my or her emotions. Now, when a piece of the past pushes its way through the ether to remind me of who I was or am, I can try to push it down—but in a quiet moment, I might be struck by the terror that some darker, more cowardly part of me is still too close for comfort, still there inside me. The hologram of my past self, its face a distorted, shadowy reflection of me with large, dark eyes, is my mirror, my muse. And any judgment of my character depends not on whether I, in some simple sense, am still that person, but whether I—whether we, multiple and overlapped—can reckon with, can meet and return the gaze of the ghosts of our past.