The day I found out I had a brain tumour, I tripped and fell. It was, as the kids say, an epic fall. I was wearing a rather tight dress and heels, so there was no possible graceful recovery. It happened just inside the door of the building my office is in, in front of the registrar and all the people coming and going. A crowd gathered around me, and I laughed it off, blaming the ring of plastic trash wrapped around my feet.

When I got to my office upstairs, I told my friend about the fall, and we explored the end result of ripped tights and skinned knees, joking as you do in the commiseration of daily annoyances.

“And I have a brain tumour,” I told him, as the end to my story.

I told almost nobody else the news, internalizing the stress and anxiety, pretending whenever I could that I was fine and life was continuing on as usual. Six months later, my knee still hasn’t healed, one of the possible side effects of the little lesion growing in my head. Maybe it’s time to tell my secret before my body tells it for me.

*

Getting sick in your thirties means you’re not following the narrative correctly. I figured I’d done enough of that already; in what the Dixie Chicks called “taking the long way around,” I’d spent most of my adult life in school, avoiding long-term commitments such as a steady job, buying a house, and having kids in favour of aiming for one of my ever-shifting professional goals. I’d racked up substantial student loan debt and did contract work four months at a time, spending many of my leisure hours at bars reviewing new country bands. I was struggling through the aftermath of getting divorced, trying to figure out how to start over, which meant I had to move into a tiny apartment that could barely contain my collection of books and instruments. A successful week for me meant I had vacuumed up the cat hair and prepared all of my lunches before going to bed on Sunday.

When I was diagnosed, I was teaching three university courses, researching for a PBS documentary, filing at an artist tax office, copyediting a journal, and booking a music venue. And those were just the paying jobs—I also worked for free as the editor of a quarterly publication on folk music, wrote regular reviews for a music website, and was starting a festival. I had three books in progress, and I was just starting to take lessons on pedal steel guitar. I went to ballet classes and my book club; I tried to keep up with House of Cards and Downton Abbey. My friends dropped by with their babies and accused me of living the “single” girl’s life, not knowing that I was in pyjamas at 10 a.m. because I hadn’t torn myself away from the computer for hours in order to accomplish the simple task of getting dressed.

So I and many others attributed my encroaching health oddities to stress. In the fall, I lost my vision at some point every day for three weeks straight, and suffered debilitating migraines. “Probably too much computer time,” came my friends’ sage advice. Then my period stopped. “Must be because your hormones are shifting,” said my doctor. “You are 36 after all.”

*

Historically, women have had a tough time getting anyone to believe they’re sick. In The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, author Rebecca Skloot documents the brief but serious ordeal of Lacks, a poor black woman whose cancer cells, known as HeLa, were the first to reproduce outside the human body and became the basis of modern medical research: “Henrietta told her doctors several times that she thought the cancer was spreading, that she could feel it moving through her, but they found nothing wrong with her.” By the time she insisted on being admitted to the hospital, Henrietta appeared to be producing new tumours “daily,” on her lymph nodes, hip bones, and labia.

Things haven’t changed much since then. I’d go into my appointments wanting to say “I’m a doctor too!” while conveniently leaving out the fact that I’m a doctor of country music, but hoping nonetheless that they might take the title as an opportunity to give me a little more time or information. I also hoped that they might believe me when I said I knew better than they when something was wrong with my body.

A “feeling” that something is wrong isn’t good enough, and that’s compounded by test results that might confirm a doctor’s suspicions. I went through a series of blood tests in the fall that came back “pristine” (my doctor’s word), reinforcing the belief she probably had that I was overreacting to my constantly itchy legs and sudden intolerance for the cold. I’m from Alberta, I wanted to tell her. Winter is my jam.

*

So it wasn’t until a bleak day in January, when I took some books back to the library and could barely walk the block home that I decided maybe it was time to really take action. I started down that scary tunnel of Googling symptoms, discovering that I might have MS, Parkinson’s, or something worse.

I decided not to tell anyone what was going on. My family was across the country; why worry them with potentially serious possibilities that may never manifest? My partner was concerned, but going through his own set of problems that distracted him and distanced us from each other. We didn’t live together, so he didn’t see it on a daily basis, never mind that at the best of times, our work schedules left us collapsed in exhaustion at the end of every week.

I got to know the quickest public transit routes to the hospitals around town. I got to know myself pretty well, too. I worked on copyedits in hospital waiting rooms, answered student emails during ultrasounds.

But those emails were piling up. “Gillian, have you sent the proofs to the guest editors yet?”

What proofs? I would wonder blankly.

“Gillian, we need a profile on Trisha Yearwood now. She is showing up to the Garth Brooks interview in 45 minutes.” That one arrived as I was downtown just coming out of an appointment.

“Miss, have you posted the essay assignment yet?” “What’s the cover charge for tonight’s show?” “Do you know where the T4 for Ronald Smith’s 2013 file is?” “Why haven’t you called home in a week? Are you okay?”

*

There was a reason I was working five jobs.

As a sessional instructor in a small university music department, I was always aware that my job could disappear in a flash. At times, it nearly did, as upper-level politics and course migration threatened to shut down our whole program. The end always hovered at the fringes of my mind, though, so I took extra courses, and applied for any job I was remotely qualified to do. It meant that some years were pretty lean, while others, like this one, seemed to burst with opportunity. I didn’t turn anything down on the assumption that it could lead somewhere better, or that I might be without my teaching job very soon.

My fear wasn’t misplaced: the number of tenure-track positions at universities across North America has shrunk. Figures differ depending on the type of institution, but anywhere from 25 to 70 percent of instructors are part-time adjuncts. In my field, there was only one tenure-track job posted in Canada last year. Pay typically ranges from $2,000 to $7,000 per course, again depending on the institution. If that isn’t precarious enough, most instructors have to wait until just a few weeks before the term begins to find out which courses, if any, they are teaching, what their schedule is, and how many students they have. And at any time, a tenured professor can take away or be assigned a course that once belonged to an adjunct.

Between paying off the debt from taking on joint expenses after my divorce and intermittent health benefits, a sick leave left me in vulnerable territory. While my seniority would technically remain intact if I left for a semester, a new instructor could come in, teach my classes, build her own seniority, and leave no place for me to return. I wouldn’t have much ground as a contract employee to demand my job back.

My prognosis terrified me mainly because I thought I would have to leave work mid-semester. My savings are paltry, and a three-to-four-week recovery from brain surgery might be all I could manage without income. What if there were complications? I hoped the surgery might be scheduled for the summer, when there was no work available to me and I wouldn’t have to pay a substitute,11While I don’t know for sure if the department would provide and pay for a substitute for a longer-term leave, usually if we have to miss classes for a week or two, my fellow instructors and I cover for substitutes out of our own paycheques. but that meant I would also have no health benefits—a “perk” I was lucky to attain over the last few years any time I was bestowed a four-month, three-course package.

I had not planned for this at all. Not now.

*

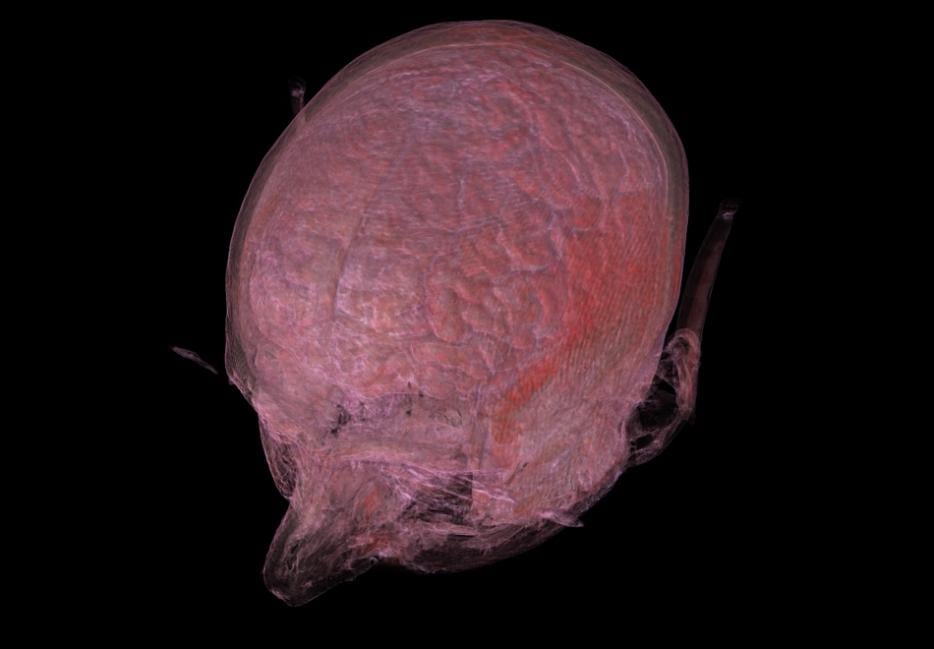

I discovered that MRIs are like 20th-century avant-garde music, wondering as I laid in the narrow tube with instructions not to move and nothing to do but keep a finger poised over the panic button if anyone had composed a piece from the sounds they emit. I dug those sounds. You can find the positive in these experiences.

My doctor called. “Your CT scan came back,” she said. I was standing at a streetcar stop waiting to go to a kidney ultrasound. “You have swelling in your pituitary area, so I’m going to order another MRI.”

In between tests, I would stop in to see her. The first MRI showed no signs of MS. The leg ultrasound came back clear. A lump in my kidney had gotten smaller. These were good things.

The day I found out, my doctor telephoned early in the morning.

“Well, I looked at your MRI results,” she said, “And really, you seem fine. Are you still having problems?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“Okay. You do indeed have a tumour on your pituitary gland.” That was the news I was expecting to hear. “It’s likely not cancer. We call it a micro adenoma.” I could barely keep up with her pace, even though I could tell from her voice that she was nervous. “So I’m going to send you to the specialist, and they’ll probably just put you on some medication. I don’t think we’ll need to do radiation or surgery at this point, but it’s not for me to decide. I’m sure you’ll be fine on the medicine. So does that sound good? Do you have any questions?” I found myself in the position of trying to reassure her, so I didn’t ask anything. Even though I’d expected the news, I was spinning. It was the weirdest call I’d ever received.

When I hung up, I saw it had only lasted two minutes.

*

Being sick often feels all the more awful because of the work of telling everyone you feel fine. There’s no room to worry yourself, even if you wanted to. It also means you have to talk a lot. I’m not a big talker—I’m quite happy to spend much social time off to the side observing, or to have my one-on-ones permeated by comfortable silence—but I’m not getting those opportunities anymore.

There was no way I could tell anyone at work. I worried that I’d find myself squeezed out by people who were “healthier”—no great feat at the adjunct level, regardless of how strong the instructors’ union may be. Worse, as a woman, I already found myself constantly under scrutiny for what I wore or how I spoke. Student evaluations were always some variation on, “She has a nice smile, and is so understanding!” while peer evaluations described the colour of my clothes and my hairstyle rather than the lectures I’d spent hours preparing. I could not show any sign of weakness. I became adept at smiling cheerfully and brushing away concerns about my health.

At this particular moment, I was up for a temporary promotion to a one-year full-time position, and I was helping to propose a minor for our department, which meant gathering and refining the necessary materials and creating new courses. My workload increased; my pay did not. That was okay, I reasoned, because it was work towards a greater goal. Should I get the promotion, it would have all been worth it. I was as agreeable as could be, and it was largely genuine: the prospect of investing my time in a place and program I really believed in was exciting. The brain tumour would have to take a backseat.

*

I got on a cancellation list for the specialist and saw her three months in advance of my original appointment. She spent about 15 minutes with me, told me not to worry, and dismissed my suggestions that the tumour was causing the symptoms that wouldn’t let up. I left the office reeling; I’d assumed that I would get some form of solution from her, and I didn’t know what to do next. I became defiant, telling everyone “If the doctors don’t care, then neither do I.” Three days later, I got word that approval for my promotion had been rejected by the university’s administration. I cheerfully told my colleagues that I understood, but I had finally collapsed inside; so much of my self-worth is wrapped up in my professional achievements that I was fighting for reasons to keep getting up in the morning.

My partner did not let me slide. He had been gently insisting on cooking me dinner and was accompanying me to appointments. That weekend, we escaped for a brief trip to Niagara Falls, feeling dizzy from the temporary release from the stress. Through the summer, he has coached me through my depression, an ever-present hopelessness threatening to drown me, and he’s encouraged me to channel my anger and energy into my creative output rather than my teaching work. We still don’t live together, but there is some comfort knowing that he won’t let me go more than a few hours without getting in touch.

I’d wrongly assumed systems I’d come to trust would always be in place. I have no hope for the education system: as long as universities funnel available resources into bloated administrative departments at the expense of secure positions for professors, they will suffer from reduced quality in instruction. The healthcare system, I’ve learned, can be managed with persistence and, often, a bit of luck: I happened to mention the tumour at my book club, and luckily my friend, who manages the Brain Tumour Research Centre at Sick Kids Hospital, put me in touch with additional specialists. I’ll get their second opinions at appointments in the fall.

And I’ll continue on as a precarious employee, hoping that at the ten-year mark this January, I’ll at least get a new course to teach as a sort of anniversary gift. But I can’t let it determine my self-worth. It will take a lot of work, but I’m getting there. Funny how hearing the words “brain tumour” makes you realign your priorities; I left town for the summer and spent long stretches ignoring my work emails. I now go for long walks and read books beside my partner with pure enjoyment and zero guilt, something I’ve never been able to do before.

Also, it’s still taking me longer than it should to answer emails. Hopefully I’ve reserved the right.