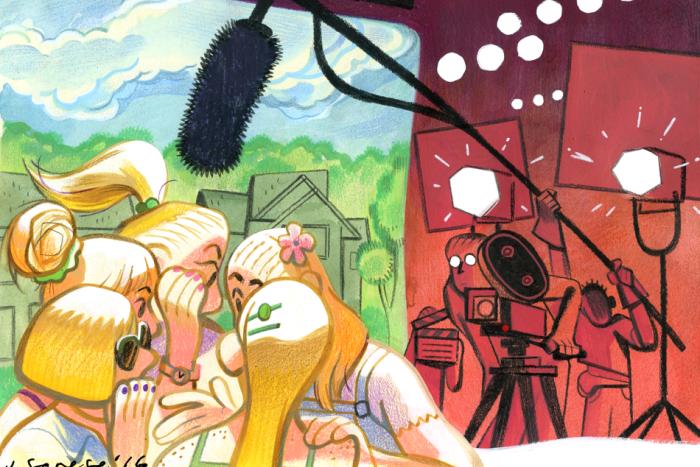

The beautiful man playing the piano wears a sequined jacket, a high-collared and ruffled blouse, eyeshadow, kohl, mascara, some sort of brocaded turban, and a look of intent distraction. This club gig is a sideline to his gigolo career, so when a wealthy older woman takes the nearest seat he starts vamping, mouth agape, as if to vacuum that cherry off her cocktail stick. “Once upon a time in France,” the voiceover says, “there lived a bad boy named Christopher Tracy.” But the Art Deco opening credits introduce him by another title: Starring Prince. Music by Prince & The Revolution. Under the Cherry Moon, a film by Prince. The 1986 romance was his directorial debut—he took over from Mary Lambert a week into production. Prince is pantomiming a seduction for himself.

Under the Cherry Moon almost seems calculated to frustrate the fans who bought Purple Rain tickets weekend after weekend. It’s a tragicomedy shot in languid black and white by Fassbinder’s cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, its French Riviera socialites idling through a circus of perpetual decadence. The only other cast member returning from Purple Rain is Morris Day henchman Jerome Benton, now playing Christopher’s fellow hustler Tricky. Prince withholds one of the two musical numbers until the final credits. The rest of Cherry Moon’s soundtrack, which saw release as Parade, bursts past the images in snippets: Prince reduces psychedelia to miniatures of dynamic stasis. Even Christopher and Tricky coming from Miami, not Minneapolis, feels like an arch geographical joke at the previous movie’s expense.

When Prince meets the patrician heiress Mary Sharon—Kristin Scott Thomas’s first film role—he starts scheming to inherit her inheritance, but the conman falls in love with the mark. (Mary’s father disapproves, and secondary Octopussy villain Steven Berkoff plays him with the sleek hairline and insinuated menace of an eel skimming its reef.) That antique premise recalls Trouble in Paradise, the 1932 Ernst Lubitsch comedy, where a flirtatious perfume magnate complicates the romance between two thieves swindling her. The sophistication governing Lubitsch’s films was a system of desire confided through repartee, euphemism, ellipsis and silhouettes. His characters would lean nonchalantly over a volcano.

In Under the Cherry Moon, all these angled mirrors spin out of place. The tone leaps around breathlessly from scene to scene, and often within one. People recite quips they wish they’d thought of last night, then flit to a new non-sequitur. After Mary protests that Christopher doesn’t really love her, he says, “Okay, I hate you.” When she first spots him at a party, everyone else scampers out of the frame, and the camera zooms slowly towards Prince, wearing a cropped bolero shirt, fingering his lips, and standing next to a toy clown. The glamour here is a spell gathering together flimsy translucencies.

If white supremacy in America is sanctified by evil fables, stylish old Hollywood movies among them, at least Prince could play his own kind of trickster figure.

Warner Bros. allowed their star to take over the shoot because Purple Rain made $70 million on a budget one-tenth the size. Prince only ostensibly went in front of the camera that time, but cinema fascinated him—an earlier project called The Second Coming fell apart after his perfectionist demands exasperated the director—and he influenced every aspect of the production, limiting every musical performance to three takes (it worked) and insisting that his personal designer Marie France would provide all the outfits. Prince’s old protégé Jill Jones told the journalist Alan Light: “We used to watch so many old films. A lot of Italian films—he loved Swept Away—old Cary Grant. He got into David Lynch at one point, so he really started looking at, like, Eraserhead; I remember screaming at that little worm-baby or whatever it was. He was looking at European directors, trying to pull all of that in. He was really into the old studio system, too, Louis B. Mayer, he had books on those, looking at how that was structured.”

Prince finished Under the Cherry Moon under budget and ahead of schedule. He also gave it the kind of casually surreal images his songs parade: Animals strike curious poses. Bats roost inside a seaside bistro; a conga line pauses watching breaths of fire; boys with pomaded hair and demonic eyeshadow bark, “We have Porsche, we have cable. How about it, baby?” Even Prince’s most elaborate metaphors, like “Little Red Corvette,” seldom constrict themselves to fill a verse; the lyrics collapse perspectives into a single fluid image. His camera keeps swooping around the parties that Christopher and Tricky crash, enamoured for a moment with the panicking servants and jaded sybarites, the piano lounging on a cliff, the petals falling from the sky. A sheen glows luminously from Prince’s hair. Curtains quiver with fluorescence.

Aside from the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman, who deemed Prince “the wittiest heterosexual clown since Mae West,” most critics reacted to all this with appalled glee. Walter Goodman of the New York Times sounded like Mary’s father; to him, Christopher was “a self-caressing twerp of dubious provenance.” That primly coded gibe should embarrass anyone calling Prince “post-racial.” But if white supremacy in America is sanctified by evil fables, stylish old Hollywood movies among them, at least he could play his own kind of trickster figure. Midway through Under the Cherry Moon, Christopher infuriates Mary and delights himself by asking what a “wrecka stow” is. (“If you wanted to buy a Sam Cooke album, where would you go?”) Her voice just stiffens helplessly, with all its ornaments of race and class, while Prince giggles into the tablecloth. Later on, he jokes about making her “get black,” squealing: “Oh, Christopher! Oh shit!”

The gigolo doesn’t only caress himself. He spares some affections for Tricky as well, calling him “honey,” playfully wrestling, saying things like: “Do you love me? Come on, you know what I’m talking about.” Tricky later declares: “I’m my own man. Like Liberace.” Their outfits say high-femme, but the banter is low camp. (Christopher Isherwood described the latter register as “a swishy boy with peroxided hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich,” which sounds like one of Prince’s early notices.) Christopher and Tricky remind me of the carousing sailors in Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers: “They spent their time doing nothing … They let intimacy fuse them.” Genet writes that “a man who fucks a man is twice a man,” leaving a riddle: What does this alchemy make of the man getting fucked?

A few friends recently sent around an interview in which Prince’s old bandmates Wendy & Lisa describe him as a “fancy lesbian.” They weren’t so close anymore, spurned first by a lack of recognition and then his deepening religious conservatism, but just before all that the trio co-wrote “Mountains,” my favourite Prince song. The lyrics are some of his simplest and most elusive: “It’s only mountains, and the sea / There’s nothing greater, you and me.” The whole band plays it over Under the Cherry Moon’s end credits, Wendy resting her guitar on her knees like an ancient lyre. No longer the martyr for love, and now onto his third crop top, Prince gyrates a tambourine. The background behind them keeps shifting, from the peaks to the waves, fading into a sky foamy with clouds.

Hundreds of miles away from the French Riviera, under the delirious blossoms of the Commune, an artist named Eugène Pottier coined the slogan “communal luxury”—that each person, no matter their status, has the right to beauty. Prince’s vanity always seemed curiously inclusive to me. Most of his protégés looked kind of like him, but anyone can look kind of like Prince. Is it merely self-absorbed to yearn for a twin, if that also demands yielding to another? I want to be all of the things you are to me, Prince sang on “If I Was Your Girlfriend.” When Christopher gazes at Mary in the dark, searching and longing, their inky eyes blur together. You can’t tell who’s seducing whom. The beads of his blouse shine against her sequins, bodies improvising a constellation.