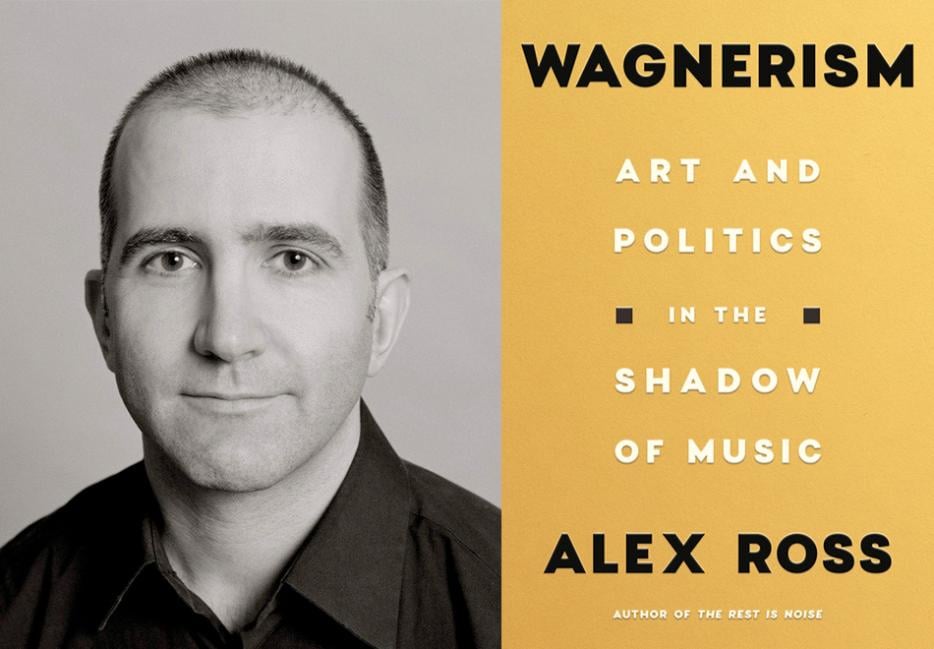

Alex Ross’s new book Wagnerism (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) opens with the death of its subject, clutching his heart in a Venetian palazzo. When Wagner’s erstwhile acolyte Friedrich Nietzsche heard the news, he fell to bed ill, overwhelmed. That malady proved incurable for Nietzsche, who still agonized over the idol-turned-rival until his mental breakdown years later, and it lingered down through the century he helped usher in. A longtime music critic at The New Yorker, Ross purposefully ignores Wagner’s own peers, focusing on how his grandly ambivalent ideas blasted through every other medium. “The composer came to represent the cultural-political unconscious of modernity,” he writes, “an aesthetic war zone in which the Western world struggled with its raging contradictions, its longings for creation and destruction, its inclinations toward beauty and violence.”

Wagnerism reaches monumental proportions. One gets the impression that Ross read everything ever published by or about Wagner, then wandered through the appendices. There are chapters on literary admirers like Willa Cather and W. E. B. Du Bois, on the ways cinema has absorbed or mimicked his music, and necessarily on Nazi Germany. Hitler adored both the deathless melodies and their creator’s grotesque anti-Semitism. Wagner told his patron Ludwig II that “I consider the Jewish race the born enemy of pure humanity”; his 1850 essay “Jewishness in Music” describes German Jews as the worms feasting on a corpse. Studies of cursed art often amount to glib apologetics, as if the author were hovering cross-legged over a prayer mat, serenely undisturbed by politics. Wagnerism climbs towards a reckoning instead, following the inferno into Valhalla.

Chris Randle: I didn't realize this until actually reading the book, but I was amazed that you eschewed any mention of Wagner's musical influence, and I'm wondering if you were always working under that restraint. Was the book in its present form from the beginning?

Alex Ross: Yeah, I decided right at the outset I wasn't going to talk about the musical influence, because it's such a huge topic in itself. There's thousands of composers who've been influenced by Wagner in one way or another—it would've added hugely to the scope of what was already a huge book. I actually don't think that the topic of Wagner's influence on music is as interesting, because there's nothing too surprising about it. He was this powerful figure in musical history, and he introduced a new musical language to some extent, especially in Tristan and Isolde, but he's not more influential than a bunch of composers who came before him, or even after him, from Monteverdi, Bach, Beethoven to Stravinsky or the Beatles or whoever. Whereas this phenomenon in the other art forms—literature, architecture, dance, film—it is kind of unique. I don't think anything quite like it had happened in cultural history.

I didn't know how prolific Wagner was outside of music, often arguably in a bad way—even outside of the anti-Semitic writing. His politics especially, I got this sense that they were never quite coherent, constantly shifting in a way that many distinct people latched onto. There's just a gigantic amount of research involved with going through that material, how did you go about all that and keep track of it?

Yeah, he wasn't just a composer, and an important fact about the work is that he also wrote the texts. There are a lot of aspects to his non-musical activity which are...distracting at best, and malignant at worst [laughs], but in terms of the dramas, he was kind of a brilliant dramatist. He wasn't an acclaimed master of the German language in terms of his literary output, and a lot of German people, when they look at the librettos in isolation, it's very difficult, this strange, mangled, pseudo-archaic version of the German language, and it's just not conventionally beautiful. But when that libretto is sung, and the singing is placed in this dramatic situation that he creates, it becomes really compelling. Wagner was actually really good at structuring acts of an opera and building tension, undertaking these ambitious stories filled with so many interesting psychological details while pursuing grand themes—power in the Ring cycle, the lust for gold and the opposite force of love, all the philosophical underpinnings.

He was a great psychologist, and all these characters are really rich; like, Wotan is so fascinating because he's this man of power who wants more power and ends up destroying himself in his need to always have more and more. He ends up plunging into this state of psychotic despair and self-pity, which is one of my favorite moments in all of Wagner. So there's a lot there, but there is also thousands of pages of the prose writings, a lot of which is just very difficult to make sense of, and yes, his politics were all over the place. If only he had simply written the music and written the texts and worked as a conductor, as a theatrical director; if only he hadn't felt the need to spew verbiage on every subject under the sun. But that was who he was, a completely irrepressible and verbose and monomaniacal figure who had to have an opinion about everything.

The research was pretty huge. I started out by going through all the operas very carefully, the scores and the librettos. I didn't read or reread all of the prose writing, but I went through the main ones. And then I just started absorbing the material needed for each chapter, so many novels, plays, poems, I don't know how many hundreds—including some big-league works of literature, like Proust and Finnegans Wake and The Waste Land and several big novels by Virginia Woolf. None of which was a chore [laughs]. Part of why the book took so long, I think, was that it was so enriching for me to revisit all this literature. Some of it I was reading for the first time, some of it I had read back in college and hadn't understood very well, and it was great to come at these classic works from a fresh angle, looking through this curious lens of how they reacted to Wagner. A lot of the book is about them, it's about this period in art and literature, and not so much about Wagner himself.

Wagner is sort of this thread that I follow through one of my favorite historical and cultural periods, the fin-de-siecle, decadent, somewhat insane, endlessly fascinating period from around 1880 to 1914. I've always been maybe unhealthily attracted to it, since I was a teenager. This fantasy-land when art reigned supreme. It just seemed like in Vienna and Berlin and other cities, artists, composers and writers were the superstars, the celebrities, and everyone in the streets was aware of their work. The cab driver would recognize Gustav Mahler on the way to the Court Opera. For me as a kid, who grew up worshipping art in all these forms, it feels like Disneyland [laughs]. But at the same time there were a lot of ominous currents underneath that world, so I'm also very mindful of how anti-Semitism was spreading, how hyper-nationalism was spreading, so it's a tale with an unhappy ending in a lot of ways.

My favorite discovery from that era might've been Joséphin Péladan, the Catholic occultist writer. He really comes off like a Ronald Firbank character, this ludicrous—

I loved writing about him. It was so much fun, he was just such a madman. You're never sure whether it was just a massive put-on, a way of seeking attention—setting himself up as the magus of this Rosicrucian order that was basically just him and putting on these wild art exhibitions, holding rituals and ceremonies. I think he was a performance artist to some extent, but also a serious, if extremely eccentric, literary figure. He wrote this 21-volume novel cycle, La Decadence latine, of which I absolutely did not read 21 volumes. I made my way through maybe four or five of them, and it's crazy stuff.

When I did my audiobook, there was one moment where I just burst out laughing while reading it, about his novel Le Gynander—the androgynous and magical figure whose mission is to convert lesbians to heterosexuality, and generates all these replicas of himself, each of whom seduces and marries a lesbian, and they all worship a giant phallus. And Wagner is playing [laughs]. It's just so crazy. But it's also part of the fabric of the time, this was a period when artists were seen to be social figures, very much in the vanguard. It was thought that art really could help bring about a revolution in society or great spiritual transformation.

You also go through a series of counter-readings: Black Wagnerites, Jewish Wagnerites, queer Wagnerites. Was there anything especially revelatory in that for you?

Yeah, at the outset I was aware of some of that material, and I definitely wanted to uncover these counter-narratives. The issue is that so many people equate Wagner completely with anti-Semitism and Hitler and Nazism, and they kind of erase everything else that went along with the phenomenon of Wagnerism. So what I was trying to do, without at all marginalizing that other narrative, that line of succession from Wagner to Hitler, which is extremely important and very real—it becomes more and more central to the book as it goes along. Without concealing that at all, I just wanted to add to the picture, to complicate it, with all these other ways in which Wagner affected people; from the far left to the far right, all these different social groups and minority groups who identified with Wagner and found him inspiring as they looked to ennoble their own traditions.

So I was aware of W. E. B. Du Bois and his love for Wagner, and I was aware of the fact that for a lot of early gay-rights activists, as gay culture emerged into the open at the end of the 19th century, Wagner was a sort of icon, seen as an ally figure or even "one of us." Some people thought that he was gay based on the very romantic letters back and forth between him and King Ludwig II, when in fact they were just these flowery letters.

And there are wonderful descriptions of Wagner's fashion sense.

Yeah, there was this androgynous side to him, he liked to wrap himself in these soft, silky fabrics, so there was this cultivation of a feminine mode of dress—which he was conscious of, and he talked about androgyny as an ideal in his work. His whole attitude towards gender and sexuality is really complicated. I mean, sometimes he can sound like a total misogynist when he talks about women, but there was something unconventional about his gender identity—it was not just standard masculinity. And that emerged into the public eye in an uncomfortable way for him when these letters to his designer-milliner about his favorite satin fabrics were exposed and published. He was widely mocked. But then somewhat later [the sexologist] Magnus Hirschfeld reviewed that episode and said, no, this is part of why Wagner is so interesting as an artist, because of this gender identity that he possessed ... There was more of that than I realized there would be.

I knew about Du Bois, but I discovered this singer Luranah Aldridge who almost sang at Bayreuth in 1896, and who was the daughter of the great Black actor Ira Aldridge. Some of that Hirschfeld stuff, I just found out more about Wagner and Hirschfeld than I realized there would be. Those sections of the book kind of grew in importance, just because I ended up feeling like it wasn't just one or two eccentric cases, this was actually a deeper phenomenon. Even the case of African American intellectuals identifying with Wagner, that was more widespread than I thought at the end of the 19th century, early 20th century.

It shows you how a figure like Wagner can be inspiring and useful to audiences and spectators who might otherwise be hostile to him—you would think, by contemporary standards, that they would've rejected him, and of course this goes for the Jewish Wagnerians as well. But in fact they felt the right to take the work and make it their own, and ignore whatever aspects of Wagner were inimical or even directly hostile to them. People in this era worshipped art to an extreme degree, but they also felt free to take it and manipulate it however they wished, and I think today we tend to feel more bound to the original intentions behind a work and the biography of the artist, the context, so some of that freewheeling approach has ebbed away. I found that relationship between spectator and artwork really interesting.

I don't know if you saw, but when Florian Schneider [a founding member of Kraftwerk] died earlier this year, people were sending around this amazing clip from 1990 or so, Detroit clubgoers on some local TV dance show just losing it to Kraftwerk's "Numbers." Obviously Kraftwerk don't have the racist baggage of Wagner, but they're easy to caricature as these impossibly white German guys, and yet they were closely intertwined with so much techno music. It is easy to reduce these things in that way.

Yeah. The side of the relationship that I've always found so interesting is—I go through a whole series of examples of people being overwhelmed by Wagner, to a degree where they're losing control, they're put under a spell. It has this narcotic effect on them, they feel drugged by the music. There's this almost sexual vocabulary of being penetrated by the music—Baudelaire says that. And yet the spectator doesn't end up being passive and powerless. At the end of the process they emerge, having reinvented Wagner for their own purposes. That's what the Baudelaire relationship is all about. At the end, despite seemingly prostrating himself before the god Wagner, his Wagner is almost unrecognizable next to the original. He's just converted Wagner into this proto-avant-garde French bohemian figure.

And that happens again and again. I'm fascinated by the doubleness of that, that you lose control, lose yourself, in the music and the work, but you emerge owning it in this very dramatic way, taking possession of it ... It's this pronounced pattern that you see over and over with a lot of these figures. The music has a strong visceral, sensual effect, but it's also extremely vague in terms of what it's actually conveying, and the spectator ends up projecting themselves into the work rather than receiving some clear message of meaning.

I really like that one detail you mention, the Jewish music fan who was a contemporary of Wagner, who had the bust of him crowned with both a laurel and a noose.

I love that. It's such a great visual encapsulation of the relationship that a lot of people had with Wagner, which is kind of my own. I meet so many people today who don't worship the man at all—they're fascinated by him and the work, but there's this adversarial, critical aspect to it too. They're constantly fighting with Wagner ... I think it's a healthy relationship to have with a work of art, to always be a little on guard and skeptical and aware, and not naively trusting the work to give you a pure and innocent and positive and uplifting message. I like that dimension of wariness [laughs] listening to Wagner. I always feel very awake and alert listening to Wagner and wondering what exactly is going on while I'm swept up in the music.

Until very recently, the prize for the World Fantasy Award was a bust of H. P. Lovecraft, and I've seen multiple essays from people who won it saying, "I turned mine to face the wall," or turned it to face a Samuel Delany book.

At another talk I was doing, during the question period, someone drew that connection between Wagner and Lovecraft. I was actually talking about African-American Wagernism, and they pointed out that the new show Lovecraft Country—I've only seen a couple episodes of it, but it feels like it has some of that same dynamic as the older Jewish engagement with Wagnerism had, or African-American Wagnerism. Du Bois was actually pretty much straightforwardly worshipful of Wagner; he objected to the anti-Semitism but he never sensed any kind of anti-Black racist threat from Wagner, so far as I know. Jews were Wagner's fixation. He didn't have very much to say about Black people.

I feel like they're similar in that they've both had this vast influence beyond their fields, Lovecraft more than he did within his own medium, but different in the sense that, if you read a random Lovecraft story, the racial paranoia really is inescapable, even when it's transposed to cosmic horror. Whereas Wagner I don't think is reducible in the same way.

Yeah, it's not blatant with Wagner. There is this recurring debate over whether there are anti-Semitic stereotypes present in the works, the dwarves in the Ring cycle or Kundry in Parsifal or Beckmesser in Meistersinger. And people have plausibly said that they do match up with anti-Semitic stereotypes. The problem is that Wagner never gave any indication that he intended such a thing, and a lot of people actually didn't pick up on it at first. It's only really in more recent decades that people have concentrated on this strain of Wagner, it wasn't widely noticed at first. It's not blatant in that way. I absolutely feel there's something there, but it's quite hard to pin it down.

But it's still the same problem. You can't look away from any of this with Wagner, you can't pretend it's not there, because he was so influential as an anti-Semite with that horrible essay he wrote in 1850, which was widely distributed. It definitely played a role in the expansion and intensification of anti-Semitism in German-speaking countries, because he was such a revered figure, and he put his weight behind anti-Semitism in a very dangerous way.

There's a running joke in the book that I love, where you're discussing people like Nietzsche or Thomas Mann who have endlessly tortured relationships with Wagner, but now and then you mention figures like Marx or Brecht who were either indifferent or disdainful towards him. Do you feel like you learned anything from those reactions as well?

Yeah, I mean, they're just fun, because there's a lot of over-the-top Wagner worship going on in the book, hopefully not from me. So it's refreshing to have someone come in and say, "This is just total repulsive nonsense." Marx was totally scornful of the whole Bayreuth operation and the commercialism of the festival. Brecht was quite dismissive. Mark Twain had some great put-downs of Wagner. So it breaks the spell a little bit, but those voices were also part of the conversation around Wagner. There was so much mockery and bitter, vicious, but funny criticism thrown his way, like the critic Eduard Hanslick, who said that the prelude to Tristan and Isolde reminded him of "the old Italian painting in which a martyr's intestines are slowly unwound from his body on a reel." [laughs] There was such a fury around Wagner right from the start, people were deeply, viscerally put off by him, just as there were people who were swept away by him.

I think some part of Wagner actually—he got very upset by all this criticism, but he was canny enough to know that it ultimately didn't do him any harm in terms of spreading his fame. There's some part of him that always had to have controversy around him, he always had to be causing a stink somewhere. He just couldn't leave it alone and have a peaceful, slowly expanding career. There always had to be this turmoil, that was just his personality.

I wanted to ask you about the way Wagner was treated under Nazi Germany—I was struck by that detail about how performances of his music actually declined during that era. You distinguish between the Nazi high command, which loved him, and his uneasy place in the popular culture of fascism, which was mostly evil kitsch. Or, like, pop songs from America.

I read about Nazi culture trying to figure out, well, just how much Wagner really was there saturating the landscape in Nazi Germany? And I came away feeling that there wasn't as much of it as people assumed, and one clear piece of evidence for that is the declining number of Wagner performances. I came to realize that the Nazis, and especially Joseph Goebbels, used a kind of American-style, technologically driven, mass-distributed culture as a way of controlling and distracting the populace. They ultimately found it much more useful to use movies and pop songs and outdoor entertainments to have that adhesive effect, more useful than so-called high culture.

There's individual bits of Wagner which are very famous, the "Ride of the Valkyries" and Siegfried's theme, but the operas themselves are huge and complicated and unwieldy, and a lot of people found them very boring, including all of these Nazi underlings who were herded to performances of Meistersinger at the annual Nuremberg party rallies, basically under Hitler's orders. And they would fall asleep, they would sell their tickets to other people, they just wouldn't show up at all, so people would be herded in from a hotel area [laughs], forced to sit through Meistersinger. This was all Hitler's maniacal idea: He loved Wagner and had grown up with Wagner, and he assumed that everyone else could have and should have the same experience, so he sort of forced it on the masses. And there was tension between that attitude of his and Goebbels's more pragmatic approach, that popular culture was much more useful in terms of keeping the populace entertained and distracted. I mean, Hitler also enjoyed Hollywood movies, so he was aware of the strong effect of that.

And the other interesting thing about Wagner in Nazi Germany is, there were some Nazis who simply didn't like Wagner, not because they weren't interested in the music or found it boring but actually because they found Wagner kind of suspect. There was just something off about Wagner. He was decadent, he was bohemian, there was something sexually off about him. There was a rumor that Wagner himself was Jewish. These sort of stories spread around, and Hitler Youth groups would be discouraged from going to Bayreuth, because it was deemed unhealthy for robust young German youths [laughs] to be exposed to this dubious, decadent composer.

And there was this gay atmosphere at Bayreuth for a long time—it was known to be a gay mecca, where you could express yourself more openly, and that went back to Wagner himself, who was welcoming to gay people in his circle. And then his son Siegfried turned out to be gay, so he always had the entourage around him, and Cosima [Wagner's widow] seemed not to mind having gay people around. So gay men and lesbians would congregate in Bayreuth. That sort of atmosphere was persisting in the 1930s, and it was felt to be problematic in the Nazi period.

But I don't want to exaggerate this. Wagner was a big propaganda figure in Nazi Germany, and Hitler did absolutely love his music. I was just trying to introduce some nuance and complexity and just point out the ways in which Wagner—there's a lot of aspects of Wagner that have nothing to do with Nazi ideology, the totalitarian ideology. When you set his anti-Semitism aside, a lot of Wagner's other political ideas are contrary to the all-powerful central state, the huge military. Wagner was always something of an anarchist when it came to political organization.

It's interesting to compare him to Richard Strauss, who I imagine was the most revered living German composer—it seems like the Nazis both admired and resented him, maybe because they sensed that he despised them. I'm always chilled by that diary entry where Goebbels wrote: "Unfortunately we still need him, but one day we shall have our own music and then we shall have no further need of this decadent neurotic."

I think that sorry tale of Richard Strauss in Nazi Germany may give you an idea of what it would've been like if Wagner himself had confronted such a state—which he couldn't possibly have done, because Wagner was a 19th-century figure and this kind of totalitarian state in its modern form didn't exist, they couldn't have imagined it. But yeah, Strauss also had these anarchistic leanings and unconventional political ideas. Music mattered to him above everything else but he thought the Nazis would be useful for advancing the cause of his own works and classical music in general, in the same way that Wagner thought the Kaiser would be able to take up his cause, and that he would become the official composer of the new German Empire, which did not happen at all.

Strauss's disdain for the Nazis—he was somewhat anti-Semitic himself, or had been when he was younger, but he absolutely rejected the idea of Jewish composers being banned and resisted various aspects of Nazi policy, and eventually it became quite uncomfortable for him because his son married a Jewish woman and his grandchildren were considered non-Aryan. Signals were sent to keep him in line, that something bad could happen to his family, so he ended up in this private misery during the later stages of Nazi Germany, emerged intact, and ended up writing his beautiful final pieces. But that gives you an idea of what happens when an independent-minded post-Wagnerian composer collides with totalitarianism, which has no patience for the eccentric, self-willed artist.

You did this whole investigation of Wagner in film; obviously there's the endless recursion of "Ride of the Valkyries," but I loved what you suggested about the use of leitmotif in cinema, and I was wondering if you could elaborate on that.

Right from the start of movie history, there was this idea that Wagner could be used as a model for how music goes together with film images. Already in the silent era, Wagner was being held up as a guide for how you identify characters and situations onscreen by tagging them with these brief motifs, and people write, "Do what Wagner did." And Wagner's own music would be part of that library of motifs, that the movie-house pianist would have at their fingertips: Horses, play "Ride of the Valkyries"; a storm, play Flying Dutchman music. So at that basic level, Wagner was integral to the development of film music.

Then when sound came in and you have these big professional orchestras recording symphonic scores by composers like Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, many of whom were emigres, who came out of this late-Romantic musical tradition, and Wagner was just inescapable in that tradition. Richard Strauss was also a huge influence, especially on Korngold, but there's Wagner all over how those scores are constructed and the orchestration. Film music is Wagnerian from the outset. In that chapter I was actually breaking my rule a little bit, not writing about Wagner's effect on composers, because I do talk about Steiner and Korngold and Bernard Hermann, but then I sort of expand it beyond what's on the soundtrack, what the composed score is doing—I'm also talking about Wagnerian motifs in the stories, versions of these classic mythic situations from Wagner's operas.

There's a whole bunch of movie scenes where people are listening to Wagner—with the rise of Nazi Germany there's this instant cliche of identifying Nazis onscreen by playing some Wagner, or they're listening to Wagner. And then more eccentric strains, Luis Bunuel with the surrealist use of Wagner, and later Fellini, Ken Russell—Lisztomania is such an incredible film [laughs], it's such a bonanza for anyone who'd been immersed in all this for years as I was. There's so many careful little inside jokes in that movie. That chapter ends with Apocalypse Now, which is kind of the masterpiece, the most amazing Wagner scene in movies.

And also maybe encapsulates the political contradictions.

Yeah, that's why it's so great, I think. It's not just incredibly viscerally effective, how it's filmed and the helicopters and the synchronization of the music to the shots, but also there's this huge irony at work where the kind of music that was so often associated with Nazi aggression in movies and newsreels is now being used to portray American military aggression. With this racist edge to it, because Robert Duvall's character has these racist insults that he throws out as the assault is underway. It's basically America beginning to take on the role of global villain, there's this transference or inversion with the Wagner music there, it's tremendously effective.

And then it sort of undermines itself, because it's so thrilling that you lose track of the ironic, subversive message, it becomes this glorious macho spectacle with Wagner playing. You have this absurd situation where soldiers are playing the music in real-life combat, just because they've seen the movie or seen the scene on YouTube or whatever, and feel like it's the right thing to do. That was not the message that the movie was supposed to be, I think [laughs], at least from Coppola. John Milius [the screenwriter] had a different political orientation. And that turnaround is also some Wagnerian irony, the scene from the movie being misappropriated and politicized in a new way.

I'm curious, why did you choose to do that abruptly memoiristic turn at the end? I thought that was fascinating, it just stands out so much from the rest of the book.

That was funny, because I'd been working on this book for 10 years, and I was finishing the draft in January of 2018—of course it had to be edited, that whole process before publication, but that was the moment where I was finally finishing the rough draft. My 50th birthday was coming up, and I told myself that I have to finish at least a semblance of a rough draft before my 50th birthday. Over Christmas I was maniacally working away. Then a couple days before my birthday I was flying back from New York to L.A., and I wrote a rough draft of that epilogue just on the plane, and I was saying, "I'm going to change all this, I'm not actually going to put all this in the book." I was sort of telling myself that I was finished by writing this stuff down, and I could claim at my birthday party, "I finished the book!" And then I left it all in the book [laughs], and never took it out.

It is much more—obviously the book isn't personal at all, it's a work of cultural history. But I thought, I don't know, I just sort of used myself as an illustration of the same kind of process that I'd been depicting with all these other figures, where they have these personal experiences with Wagner and these unexpected associations come into play. They find this new relationship between the music and their own world. I realized that that had been happening to me, and I'd been replicating this familiar mechanism of relating to Wagner. Struggling with Wagner too, because I wrote about how I hated Wagner when I first heard him, I saw him as this huge historical problem when I was studying European history and culture in college, and then I developed this deeper appreciation for him. So that was...experimental.

I guess usually with a huge book like this, on a topic that's maybe a little bit obscure, the author would usually put that kind of personal introduction at the beginning, to create relatability or something [laughs], and I guess I was being a little perverse by putting it all the way at the end and making people suffer through [laughs]. My own take on all this just didn't matter so much, that's not what the book is about, but I thought it would be—just confess my own personal stake at the end. It was this funny story, or funny in retrospect, of how I got dumped immediately after a performance of Die Walküre at the San Francisco Opera, and then proceeded to sit through the remaining two operas with my now-ex-boyfriend, because I didn't want to seem to be too destroyed by this, even though I was [laughs].

Five or six hours of Wagner operas with this guy, it was a disaster. That kind of personal misery and humiliation, all this dark emotional stuff, I just saw that in the opera. Wagner loved to depict that kind of emotional state in his work, so that was jumping out at me as I was watching the opera, and I realized how amazingly piercing his psychological insights are.

Do you have a sense of how the Wagnerian is shifting or mutating in our own time?

I don't know, it's so complicated. He's still so controversial—people love him or hate him or can't make up their minds about him. A lot of what I describe in terms of Wagnerism in arts and literature, having these deep relationships with Wagner, a lot of that has ebbed away, but it's still going on, and you still find Wagnerian references in literature and there's still Wagner all over the movies. But there's also this philosophical conversation around Wagner, and I talk about contemporary philosophers like Alain Badiou and Slavoj Žižek who've written about Wagner. I feel like there have been these waves with him: After World War II, there was consciousness of his dark political legacy, and some people tried to respond by emphasizing his connection with leftist politics, and other people really wanted to focus on the anti-Semitism and emphasize what had been covered up previously about Wagner's racism.

I feel like maybe in the past 10 or 15 years, just in terms of the books that have come out—I talk about this wonderful book by Laurence Dreyfus about Wagner and sexuality, and that's been a revelatory book for a lot of people. People are still talking about the leftist angle of Wagner and trying to find that balance, in terms of figuring out Wagner's politics. And the way Wagner is staged is so wildly diverse as well, especially in Europe. You have no idea what you're ever going to get when you walk into a Wagner production, and that's good. Some of these productions are a little nonsensical at times, but the project is a really serious one, and sometimes those productions are revelatory, because they rip the operas away from the traditional situations and context; it can reveal powerful new layers in the works themselves and make you think very differently about them.

I actually resent when people call some random superhero movie "Wagnerian," because I think they're all terrible and I hate them. Like, Jack Kirby is Wagnerian. Those things are not Wagnerian [laughs].

The word Wagnerian just gets thrown around a lot [laughs]. When people say "Wagnerian," they always mean grandiose and bombastic and bulked-up superheroes wielding weapons, and that's only part of what Wagner is about. So often all that grandiosity is a background, and what really matters is the psychology of these intimate interactions. The grandiosity is a foil. And it's why those psychological, intimate moments have such an effect against this huge landscape, to suddenly be so close with the emotional nitty-gritty of people's lives. It's startling when you zoom in on the individual in that way, like a wide shot and a close-up. At the end of the book I give some examples of the gross overuse of the word "Wagnerian" [laughs]. I was getting a Google alert, actually, and every week it'd just be crazier and crazier. I had to shut it off eventually, because it was too much. If nothing else, maybe the book will make people think twice about using the word "Wagnerian."

Is there anything else you want to say about the book?

I do hope that it makes people rethink whatever assumptions they might have about Wagner—I do think these are tremendous works of art, and they're absolutely worth getting to know despite the huge problems attendant on them. I think you can be aware of all that and still have this very personal relationship with the work. If you're not thinking about the bigger historical questions all the time I think that's okay, you don't always need to be focused on that. You can lose yourself in the work and then step back and regain that larger perspective, with all its troubling aspects. And I think we can do that with any artwork. There's some kind of evil, there's something foul, behind every great work of art in history. Nothing has ever come from some place of innocence and purity.

What's that Adorno line...?

"Every work of art is an uncommitted crime." Or Walter Benjamin, "Every document of civilization is at the same time a document of barbarism." And those are sort of typically over-the-top, club-you-over-the-head Frankfurt School proclamations [laughs], but there's also a deep truth there, I think. I feel like sometimes with Wagner they just want to shove him to the side, like, this artist was so awful that we just can't deal with him. But the problematic assumption with that can be, if we just get rid of this figure and a few other bad apples, then everything that's left will be okay, when it's not. Systemically, in terms of racism and misogyny and homophobia, our whole cultural history is scattered with that, so it doesn't do any good to get rid of Wagner, because he's just an extreme representation of these omnipresent wounds, that we have to be aware of and come to terms with.