One spring day, a woman living in a Canadian city emailed a couple she’d never met, who lived in another Canadian city, and told them she might be interested in carrying a baby for them. She’d seen their ad on Surrogate Mothers Online, a site that connects women who are willing to gestate other people’s children with people who need that kind of help.

She told the couple a bit about herself. She was in her early thirties and had just finished up a master’s. She was not a Canadian citizen, but was hoping to become a permanent resident. She did not smoke, drink or do drugs; she ate carefully and was into fitness. She gave them her name, and would like me to use it here, but for various reasons, including the fact that she signed away her right to ever tell this story, I’ll just call her Sophie Gil.

Gil had first thought about surrogacy when she’d been approached years earlier by a couple in her birth country, but her family had dissuaded her. She’d always kept it in the back of her mind, though. She was pretty sure she didn’t ever want to have children of her own, but she was intrigued by the idea of pregnancy. “I would love to give back the joy and love that I have felt in my life ... that some only feel they can have through a child,” she wrote to the couple. She meant it. “Please let me know if you are at all interested.”

They were interested. The woman wrote right back. (The couple has declined to participate in this article.) She told Gil about her struggles with infertility. She and her husband had been trying to have kids for several years. She was in her late thirties before doctors realized she had a medical condition that was getting in the way; they corrected it. A number of times she became pregnant and miscarried. A subsequent time she’d used a donor egg and in vitro fertilization but she had lost that baby fairly late in the pregnancy.

After that scare, the couple had found a surrogate. They had some frozen embryos left over from their donor egg cycle, but those embryos didn’t thaw well, and it didn’t work out. They were all set to do a second egg donation and fresh embryo transfer when the woman who’d promised to carry their child found out she was pregnant with her own.

The mom-to-be warned Gil that being a gestational carrier would be a lot of work. Even before the pregnancy itself, she said, there were forms to fill out, tests to be done, a contract to be signed. She wrote that she wanted Gil to know these things in advance, so she could make an informed decision.

The two women exchanged several more emails that first day, to get to know each other better. Both women had pets they doted on and they shared photos of the animals. They also shared photos of themselves. In hers, Gil looked elegant but strong, with long, dark hair and a broad, bright smile. The mom shared a happy holiday pic of herself and her husband.

Just one day after first meeting online, the intended mom sent over a draft contract, left over from the previous surrogacy arrangement, for Gil to look over. She told her they would pay $20,000, plus an additional $3,500 if there were twins.

Gil had been sincere about her desire to help the couple, but she also needed the money. She had just graduated and was making ends meet by looking after children and doing some housecleaning. She mentioned to the would-be mom that she was in Canada on a student visa that would expire in a few months, but that she hoped to get a work visa by then, which she assumed would give her access to healthcare. She learned a few weeks later that she was not eligible for provincial healthcare.

Fifteen days after their first email exchange, the couple travelled to where Gil lived and met her for dinner. Gil found them a little stiff, and a tad overbearing. When she ordered seafood, the mom reminded her that she wouldn’t be able to eat sushi when she was pregnant. But mostly they were straightforward and businesslike, which Gil liked. They seemed the kind of people you could count on not to back out halfway through a pregnancy, something that had worried her.

“I think they came to the meeting prepared to offer me a deal,” recalls Gil. But she still wasn’t ready to commit. She knew pregnancy was not trivial, and, because she had struggled with negative body image for years, and had had an eating disorder, she was worried about how weight gain would affect her psychologically.

But just two months after first contact, all parties were on board. The would-be mother emailed to say that she’d be sending over a revised version of the contract. It had been drawn up by a fertility lawyer representing the couple. Surrogates are advised to get their own lawyers to read over contracts before they sign on, a service the commissioning parents usually pay for. Gil was part of an online surrogacy community, and other members were urging her to get her own representation.

But instead, the mother made a proposal. “In an attempt to try to keep costs down,” she wrote, “we were wondering if you really did want to use a lawyer.” It would cost about $1,000 just to have Gil go in and sign the contract, and since their lawyer was so good anyway, there was no need for a second opinion. Gil had some travel planned, and the mother wrote, “It would be nice if we can get the contract done and out of the way before you go away…. If you use a lawyer, this may not be possible.” Then, she offered a small inducement: “We thought, maybe we can both benefit, and split the savings ($500 for each of us).”

Gil was not sure what to do. She had a few concerns, for instance, about what bed rest would mean for her financially. Would she really not be able to work during the pregnancy? If she couldn’t work, would she only collect part of her pay? If so, how would she survive? The mom reassured her they would take care of her financially. Gil also worried about the number of embryos. She didn’t want to be pregnant with twins.

Finally, Gil wrote back to the mother. “...[B]ecause I trust you guys a lot, I think I am ok to not use a lawyer. In truth, if it were free, I would for sure meet with her. But I too am frugle [sic] and want to help save you money. Everyone has advised me to get a lawyer up till now. But…I am ok going without.... IF there is something in the contract that bothers me I trust you enough to explain and clarify.”

Gil had not even read the final contract yet—just a draft. But six days after seeing the final version, and without the benefit of legal advice, she signed it. One week after that, aware that their surrogate had no provincial health coverage and would require private insurance, both would-be parents put their names on it too. The surrogacy was a go.

*

Having a signed legal document mapping out how their arrangement was going to work was comforting to both sides. It put into words their central intention: that Gil would carry a child genetically unrelated to herself, but related to the dad, and she would give it to the parents immediately upon its birth. In return, she would get $20,000.

Actually, the “confidential agreement” was not quite that straightforward about the money. It couldn’t be, because it’s illegal in Canada to pay someone outright to carry a child for you. According to the 2004 Assisted Human Reproduction Act, doing so is a criminal offense, and could bring penalties of up to ten years in prison and $500,000 in fines to the commissioning parents, or anyone knowingly involved in arranging such a commercial transaction. (Surrogates do not commit an offense by accepting money for carrying a baby.) So, the parents used a ruse not uncommon in Canada, which involves pretending that the surrogate is carrying the child without pay, and exchanging the money under the guise of expenses, called “expenditures” in the act, which are allowed. Conveniently for those using this scheme, Canadian lawmakers have never said which expenses are legitimate and which aren’t. No regulations have been proclaimed, but Health Canada's website now provides guidelines, though these have not been made law.

Page one of Gil’s agreement contained the statement that “The Gestational Carrier has offered to carry the Child on an altruistic basis, and only those out of pocket expenses related to the surrogacy shall be reimbursed to her”; all three parties initialed it. They also initialed a page on which those expenses were spelled out in some detail, and were said to include things such as travel costs related to the surrogacy and prenatal vitamins and supplements, but also all food consumed by Gil from two weeks before the embryo transfer to seventeen weeks after the birth, and all internet and cell phone fees incurred during this time. On another page, all signed on to the idea that only expenses with receipts would be reimbursed.

On the second-last page of the more than thirty-page document was a grid laying out maximum amounts that would be used to cover expenses during certain timeframes. Specifically, up to $1,600 could be claimed prior to the pregnancy, $1,000 during the first trimester, $1,000 for each of months four through eight, $2,400 during the ninth month and $10,000 following the birth. But although in the agreement these are presented as caps for expenses, the parties understood that it was in fact a payment schedule, and that all these sums would be transferred, receipts or no receipts. If challenged by authorities, the parents would say it was to cover the expenses listed in the agreement. The mother agreed to make the payments by e-transfer.

It was a leap of faith for Gil, who was trusting the word of the parents over what she’d actually signed. But it was also risky for the parents. Not only were they committing to making those so-called “expense” payments, they had also given their word that they would pay the real expenses, like travel, medical costs and lost wages. And of course, if found out, they could be convicted of a crime.

Minimizing that risk—of anyone finding out the parents were paying their surrogate—the agreement contains an extensive confidentiality clause. It says that Gil could only tell “immediate” family and her “closest” friends that she was a surrogate at all, and even then, it instructed her to describe the intended mother as “a friend” and that “no further detail of any nature may be given.” In particular, it warns Gil away from providing any information about “activities contemplated or carried out.”

Despite the faith both parties placed in their agreement, which typically costs a few thousand dollars to prepare, it’s not clear that such agreements are even binding. Gil and the family referred to it as a “contract,” but, notably, in an email at least, the lawyer didn’t. Anyone who knows the basics of contract law, says Ubaka Ogbogu, a health law professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, knows that in order for a contract to be binding, something called “consideration” must change hands. Typically, that is money.

Legal experts disagree about whether some other kind of exchange might count as "consideration" in a surrogacy—maybe a gift or even something intangible—but to Ogbogu it seems straightforward. The Assisted Human Reproduction Act expressly forbids paying consideration between a commissioning parent and a surrogate. So, either the contract contains no consideration and is therefore not binding, or the contract contains consideration, is therefore unlawful, and so is not binding. “Under Canadian law, you cannot have a surrogacy contract,” says Ogbogu. “The contract is unenforceable.”

*

Regardless of its possible impotence in a courtroom, as far as Gil and the commissioning couple were concerned, the agreement was sacred, and both sides were committed to following it as closely as possible. For her part, Gil worried that if she contravened even the finest detail of the agreement—the prohibitions on consuming aspartame, for instance, or having unprotected sex—she would not get the pay or would be left with a child she didn’t want.

Things got underway quickly. Just weeks after signing, Gil had a medical assessment with the IVF doctor. One of the many things stipulated in the agreement was that a particular physician, based in the United States, would be the one handling the embryo transfer. Gil was comfortable with the idea of going to that clinic, because, among other reasons, one of her brothers was living nearby at the time. The couple had an anonymous egg donor lined up there, and, unlike in Canada, in the US it was legal to pay the donor for her help.

Some of the women in Gil’s surrogate community told her that American clinics were willing to transfer more embryos than Canadian clinics. In two places, the agreement Gil signed mentions as many as four embryos being transferred. Gil was a little nervous about the prospect of carrying more than one baby. She’d raised that concern in an email sent to the prospective parents the month after they’d met online. “I would like to talk more about twins...that specifically makes me a bit nervous. What are the chances?” They’d assured her that probably only one embryo would take.

But the surrogates in Gil’s online support network were advising her not to do it. They said that if the embryos were made from young eggs and then put into a healthy surrogate like her, there was too high a risk of multiples. As the day of the actual transfer approached, the idea of four embryos started to weigh on Gil. She emailed the mom. “Who decides how many embryos to transfer? … I know you are the expert...but I just want to get super informed. Four seems a lot. Am I being wimpy?” The mom replied, “I know you’re worried about how many to put in, but [we] really need this to work out. They will at least put in 3. That’s usually the norm. As for the fourth, we would have to see based on the quality. It will be the doctor and I that will decide.”

Gil made the drive across the border and down to the clinic and showed up at the appointed time. Gil remembers that the mom had reassured her that they’d discuss the number of embryos with the doctor, in advance, and that she knew the idea of four made Gil uncomfortable. But instead, Gil says the decision was made in a split second, as she was lying half-naked on the transfer room table, covered only by a sheet, legs in stirrups. The doctor, sitting in front of her vagina, gloving up, asked if they’d decided on four. The parents said yes. The doctor slipped one end of a thin plastic tube into Gil’s body, on the other end of which was a small plunger, which he pressed gently, releasing four embryos into Gil’s womb.

The mom, standing at Gil’s left shoulder and holding her hand, was so happy she was crying. But Gil was in shock. “There was a complete moment of disbelief. It was like the air was sucked out of the room for a second,” she recalls.

Had Gil had independent counsel, she might have learned that what the mom had told her was wrong: it was Gil alone who had the final say about how many embryos could be placed inside her body, and she had until the moment before the procedure began to make up her mind. “You cannot contract out your consent to medical treatment,” says Ogbogu. What’s more, he says, consent has to be procured without duress, or it’s not consent. Giving final consent while lying half-naked on a table with the commissioning parents in the room doesn’t seem, to him, to meet that standard.

If she’d had a lawyer acting on her behalf, that lawyer might have underscored that it was Gil’s decision. Her fellow surrogates were telling her four embryos were too many. Any doctor with Gil’s wellbeing front of mind would have told her the same. According to Neal Mahutte, a fertility doctor at the Montreal Fertility Centre and past president of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society, professional guidelines in both the US and Canada recommend transferring only one embryo, or at most two, when donors and surrogates are both young and healthy. “[U]nless I am missing something about this case,” he told me in an email, “this transfer went well beyond those guidelines.” Research has shown that transferring that many embryos doesn’t improve the chance of live birth, he added. All it does is increase the risk of multiple fetuses and complications.

*

Three days after the transfer, Gil went home. She wrote in one of her almost daily email exchanges with the mom that she wished she could tell if it worked.

The two women weren’t best friends, by any means, but they had, through circumstance, become intimates. Gil shared details about her man troubles and her shaky finances. The mom talked about pressures at work. At times, they chatted like girlfriends about eyeliner and TV shows. The mom had been through the fertility mill herself, so they could joke together about hormone injections and uterine linings. The older woman was attentive, and told Gil to call, day or night, if she needed support. She told her how grateful she was to have found her. Gil responded in kind: “Thanks for always being there.”

A blood test about ten days later revealed that Gil was indeed pregnant. “OMG I have so much to tell you!!!!!” the mom typed. “I just got off the phone....you are for sure pregnant!” Gil replied: “ARE YOU SERIOUS! ARE THEY SURE?...CONGRATS TO YOU!!” Gil was told to book an ultrasound for two weeks later.

On that day, Gil learned that, not only was she pregnant, she was carrying quadruplets. Gil remembers being alone in the ultrasound room with the local doctor, and she recalls that he stared at the screen for a long time before speaking. He was visibly upset. When he’d met Gil before the transfer, to check her lining, he’d warned her that if they put in four embryos, four would grow. He was against even a twin pregnancy, and he had told her so. Now, after breaking the news, and seeing her in shock, he said, “I can’t believe you let them do this to you.” She was horrified, but also embarrassed. “I felt like an ass,” she says.

The parents took the news well when they heard it. The mom told Gil not to worry, that a few of them probably wouldn’t survive anyway. But two weeks after that first ultrasound, a second scan revealed what everyone had dreaded: all four were still there, and all four were thriving.

No one thought four babies was a good idea, so talk turned immediately to what’s known in the industry as “selective reduction.” This is a procedure to terminate excess fetuses. The possibility had been discussed in advance of the agreement, and written into it, and both sides had signed on; they remained in complete agreement that it was now necessary.

Halfway through the twelfth week of gestation, Gil and the parents went to a hospital for the reduction. According to hospital records, fetus one and fetus four were selected for what they called “foeticide”: each was injected with two millilitres of potassium chloride to the heart. It took fifteen minutes. The procedure may have been quick, but it was extremely painful, and the mom held Gil’s hand to comfort her. Gil would now carry the dead fetuses alongside their two live siblings until the end of the pregnancy.

*

It was in a dialogue over morning sickness that the first signs of tension between Gil and the intended parents began to appear. In emails to the couple just a few weeks after the pregnancy was confirmed, Gil had described her “severe all day nausea” and said that “no matter if I eat, walk, work...sleep....I feel sick to my stomach.” She started taking a morning sickness drug, Diclectin, but it didn’t help. Gil’s sister, who was a nurse-practitioner and herself pregnant at the time, told her it hadn’t worked for her either, and suggested something that had: a combination of two anti-nausea drugs, Zofran and Reglan.

When Gil proposed Zofran to the parents, though, they bristled. It was partly the cost: “Wow, $20 a pill is really a lot for us to swallow on top of everything else...,” the mom wrote when Gil first brought it up. But the couple was also concerned about their babies being exposed to drugs. “Popping too many pills is never a good idea when pregnant,” wrote the mom. She included some websites about how to manage morning sickness with foods, and she suggested eating crackers.

What followed were some testy exchanges about money. “...I just want to make sure that you know that I know that taking me on as a surrogate has been extra expense for you. This affects all the decisions I make...” Gil wrote. She was living from paycheque to paycheque, and in the lag between paying out of pocket for the high-priced fertility drugs and doctors’ visits and being reimbursed for them, she found herself completely broke. “I think it is best for me not to know just how stretched your budget is cause it really really stresses me out...I promise not to ask for anything outrageous unless I feel it really is needed...”

Then she mentioned that almost everyone she knew who’d carried twins needed bed rest toward the end of their pregnancies, and she worried in an email that the couple would not be able to afford to pay for her lost wages if that happened to her. “Thank you for your concern, but we can manage with our finances,” the mom shot back. She reminded Gil that it was her and her husband’s decision how many children they could afford.

The real costs of the surrogacy were not insignificant. The parents were paying for drugs, medical procedures, travel, health insurance—all on top of the fees that they were disbursing according to the fictitious expense payment plan. Despite that, the parents were quick to reimburse and respectful about doing so. When a big insurance installment was automatically charged to Gil’s credit card one month, for instance, the dad volunteered to transfer the money well in advance of the statement’s due date, so she wouldn’t be left short.

Most of their emails were still friendly and supportive, but the strain of their complex relationship occasionally broke through. There were disagreements about travel: Gil packed in a lot and the mom urged her to take it easy. And about exercise; the mom thought she overdid things. As for a question about whether or not she’d be attending key medical appointments, the mom wrote: “Of course, I will be there for the tests and procedures. Why wouldn’t I be? I am the mother of the babies and I am doing my best to do everything I can to be there for them and for you.”

Around the sixth month, Gil mentioned that she’d called an acupuncturist to help her deal with her left leg, which was so swollen that she could no longer bend her knee or wear her usual pants. “[A]s much as I really am a cheap-ass and don’t want the extra expense....I think that if it does help...it can only make for a healthier me, a better third trimester and and and....keep me off bed rest or something horrible like that. So I think that trying this preventative action is well worth it.”

Gil says she mentioned the idea not because she was asking them to pay, but because she knew the mom had strong views about interventions. She’d already vetoed aspartame, the anti-nausea med and a flu vaccine. But the mom appeared to regard it as a bid for yet more money: “About the acupuncturist...How much does it cost?... I think floating in the pool is a better option...Sorry, but I really don’t want to spen [sic] hundreds of dollars on something that won’t work.” But eventually, the mom relented on acupuncture.

*

From the outset, the plan was that Gil would move to the city and province where the parents lived towards the end of the pregnancy. She would live with or near the parents, and give birth in a local hospital. Laws vary by province but at the time, in both provinces, the dad would be the legal dad from the start, and the legal mom would be the woman who gave birth—Gil. Where the parents lived, though, the intended mother could become a legal parent through what’s known as a “declaration of parentage,” which involves their lawyer going before a judge with evidence that this was everyone’s intention. If the babies were born where Gil lived, though, surrogacy was not legally recognized at all and the mom would probably have to adopt.

In anticipation of this, Gil travelled to where the parents lived in week twenty-six of her pregnancy, to meet and be checked over by the doctor who would be overseeing the birth. She and the couple attended the appointment together. According to the medical record, the doctor checked her weight, blood pressure, hemoglobin and a few other things, all of which seemed fine. “She is feeling well,” he noted, “apart from some edema [water retention].”

In fact, Gil was not feeling particularly well. Just traveling to the appointment was difficult, she recalls. She could hardly bend her knees and was worried she would not be able to sit all crunched up for the journey. She remembers having trouble getting up onto the examination table. In an email sent the day before, Gil had written to the mom: “My left eye is still mostly swollen shut right now... I look like a pirate!” The day before that, she’d mentioned buying some maternity clothes and that one leg was much more swollen than the other: “I had to buy an entire size up in the pants to get it to fit my left leg. The difference in leg size is crazy!” About her acupuncture treatment the day before that, she wrote: “I actually leaked lymph fluid out of the needle holes when she was done.”

Gil was still working a patchwork of jobs, which sometimes kept her busy from early morning until late at night. She was also spending a lot of time booking and attending medical appointments, chasing down medical records and faxing them to the various doctors responsible for her pregnancy care, and was now, along with the parents, looking for a place to live when she moved nearby. The parents had originally thought she’d live in an upstairs room, but they decided it would be too hard for a woman pregnant with twins. They were also worried that their various animals might not get along. Now that they were looking at apartments, though, the couple was worrying about cost, and wondering whether Gil could stay in their study.

Everything changed just eleven days after Gil returned home from that appointment, when she woke with her left eye swollen completely shut. For weeks, her face, hands and legs had been swelling, but now she could barely walk. Even her lower back was puffy, she told her online surrogate friends. She was particularly distraught about it because she was supposed to travel to a university in another city for a meeting that would determine whether or not she was accepted into a program the following year. Instead, she was stuck in bed.

She emailed the mom to tell her what had happened. Gil made it clear she wasn’t well enough to work. She wanted to know if they would pay her lost wages until she recovered. According to the agreement, she could only be paid lost wages if she had a doctor’s note calling for bed rest, but it was a Saturday, so she couldn’t get one. She had a regular appointment scheduled for five days later, but she couldn’t get by without being paid during that time. She mentioned she was thinking of going to the emergency room.

In an online post to her surrogate friends that day, Gil wrote about the phone conversation that followed. According to Gil, the mom told her she was just like “every other surrogate”—going after the parents for money so she could sit on her ass and collect. Gil wrote, “She said who was *I* to put myself on bedrest...I told her I CAN’T WALK. My BP is up and I feel terrible... And then she launched into the fact that she has been upset all along that I have been prioritizing my [career] over her babies and that I was a bad surrogate and she could never forgive me if something happened to the babies... She just went on and on. That she really had misread me and had thought I was different and not a money hungry surro but in the end I am like them all. She said that she is already paying tons of money for these babies and won’t do a penny more....that I should be ashamed. I just shut up and let her talk.”

The mother told her in no uncertain terms, Gil wrote to the group, not to go to emergency. As a non-citizen who wasn’t yet a permanent resident, Gil was not covered by provincial health care, and according to Gil, the mother argued that a visit to the ER would be too expensive. In the end, Gil promised to just go to her doctor’s office on Monday, even though she didn’t have an appointment, and see if he would look her over. “Then I hung up,” she continued in her post to the other surrogates, “and I have not stopped crying.... I just feel so crushed and hurt....It so ruins the whole connection I thought we had. I guess I really was dumb and in the end no one really really really is happy to pay you for ANYTHING even if it means helping the[m] have children that they always wanted....I have no idea where to go from here to patch things up.”

The surrogates on the message board were livid. One said she had to pace for five minutes before she could steady her hands enough to type. Others pointed out that Gil’s symptoms were worrisome. One replied: “My immediate thought when you said you don’t know where to go from here was GO TO THE HOSPITAL!!”

So Gil did.

*

Gil had been mistaken to think at the very beginning that she would have coverage under the province’s public health insurance plan, but she had been upfront about this with the parents before the agreement was signed. She had said she understood if they wanted to find somebody else. Instead, they opted to purchase private coverage.

Even before signing the surrogacy agreement, they bought a policy in Gil’s name that would cover the costs of pregnancy and a hospital birth. But it would not kick in until ten months after signing—which turned out to be only three and half weeks shy of the due date. The couple purchased another medical insurance policy to specifically cover pregnancy complications, but it would only cover the first and second trimesters. That meant that for weeks twenty-six through thirty-six of the pregnancy, Gil was uninsured.

It was during this coverage gap that she found herself so swollen she could barely move. Sunday morning, when her blood pressure measured 163/104, she called a cab and headed to the emergency room of the only hospital she knew—the place where she’d had the reduction. She walked into the ER and said, “I think I’m very sick.” The looks on the nurses’ faces suggested they thought so too, and Gil was quickly triaged and admitted. She figured they would keep her in for a day or two to stabilize her then send her home.

Around noon, however, a doctor came in to discuss the plan. The first thing they would do, he said, was give her a steroid shot to help the babies’ lungs develop. Gil was startled: she knew that was something doctors did to get a preemie ready for birth. “You’re going to deliver the babies?” she asked. He told her they had to, or she wouldn’t survive.

She was suffering from preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication. Doctors started scrawling the word “HELLP” in her notes, indicating that she was suffering from what’s considered by some to be an extreme variant of the condition, known as HELLP syndrome: H for hemolysis, the destruction of red blood cells, EL for elevated liver enzymes, indicating liver damage, and LP for low platelet count. According to hospital notes, her condition was “severe,” the water retention so significant that when her skin was pressed with a finger, it made an eight-millimetre indentation. Her blood pressure was high. Her lab tests were worrisome. Doctors were concerned about a blood clot or organ failure. The only cure, they said, was to get the babies out.

Gil reminded the doctors that these were not her babies, that the parents had to be notified. They promised to do that, but also made it clear that her health came first. “They said, ‘We’re not going to save the babies at risk of losing you. That just doesn’t happen.’”

Doctors began inducing labour with Pitocin just after midnight, and they continued to infuse her at intervals throughout the night. But one of the babies wasn’t doing so well, so in the morning they told her she had to have an emergency C-section—right away. The doctor prepared her for what was about to happen: within forty-five seconds, he said, she would be surrounded by people—a separate neonatal team for each twin, multiple doctors, about twenty people in total—but, he assured her, she would be in good hands. “It was like they kicked the door open,” she recalls, “and I was swarmed with people shouting orders and yelling...I was scared.”

Minutes later, the two babies were born, small but alive. They were just twenty-eight weeks and five days old, not quite three-quarters of the way through a full gestation. The parents did not arrive in time to witness the births—hospital notes suggest they weren’t informed until early that morning—but they stayed that day and the next.

Gil believed the worst was over. “I thought, ‘The babies are alive and I’m alive and now I just have to heal.’” But she was still in danger. Her blood pressure was still very high, she was still extremely swollen, and tests revealed that her liver was struggling. She was transferred to the intensive care unit, where she stayed for three days while they stabilized her. Her brother, who had travelled the very first night to be with her, now stayed by her side.

Three days after the birth, she was finally well enough to be moved from the ICU to a regular hospital room. She was also able to take a few steps, so, at the suggestion of the parents, she went up to see the babies. She was surprised at how beautifully formed they were, despite being so little. “I didn’t know how I would feel,” she says. “And maybe if I hadn’t almost died I would have had room in my mind to think, ‘Oh, I carried those babies.’ But there was no connection at all, no longing to nestle them or hold them or hang out with them or anything.”

After returning to her hospital room, Gil and her brother say, she received a text from the mom, imploring Gil to ask doctors if she could be discharged, because her stay was costing too much money. Gil’s brother, who’d stepped out for to get some food, now found her in her room “sobbing,” saying she had to leave. “If she’d had the choice, she might have tried to do that,” he says.

He was furious. He told her not to reply—not to communicate with the parents at all for a while. He took over, and in an email to the parents, he acknowledged that things hadn’t turned out the way they’d planned, but the focus had to be on his sister’s health, not their costs. The dad wrote back and apologized. But he emphasized again how expensive the hospital was—$6,000 per day, he said—and wondered whether she couldn’t be an outpatient.

“It was troubling to me that her health and well-being was not top priority,” says Gil’s brother. “This was very upsetting to her. I think it delayed her recovery.” According to hospital records, doctors were concerned about a sudden rise in blood pressure that day, up from 130/80 in the morning to 160/100 at 5 p.m. They noted the following day that she’d been crying a lot and her blood pressure was unimproved at 170/100.

Seven days after showing up at the hospital, Gil was discharged. Her blood pressure was still higher than normal, and doctors had scheduled follow-up appointments to check on her liver and incision. She was glad to be out, but she felt strange. Amid the larger medical crisis over saving her life, the fact that she’d been pregnant and given birth had mostly been forgotten. Little was said about what to expect of post-partum life—the bleeding, the hair loss, the moodiness—and as she moved back into the world, among people who had no idea what she’d just been through, it was as though none of this had happened. As though she’d never had babies at all.

*

The couple’s response to her illness marked a turning point for Gil. “Had it not been for that phone call... I would have SO trusted them,” she wrote to another surrogate a few days after she got out of hospital. Then, being asked if she could check herself out of the hospital because they couldn’t afford it just added fuel to the fire. Gil began to worry that the parents might actually try to stiff her. Some members of her surrogate community worried about this too.

There was a lot owing—not just the bulk of the pay, but also the hospital charges and fees for follow-up care, all of which would be billed directly to her. Her only leverage—and she knew it—was that the babies were considered hers under the law until she signed them over. She decided she wouldn’t do that until she was at least paid the full sum promised in the agreement. More than three-quarters was still outstanding.

The day after getting out of the hospital, Gil had contacted the dad to settle accounts. He’d been friendly and matter-of-fact, describing the surrogacy relationship as “wonderful for the most part” and the blow-outs at the end as “rough spots.” He agreed with Gil’s calculations—that all the payments, even for months eight and nine, which didn’t end up happening, were owing—and he even pointed out that she hadn’t received the seventh month payment, so he added that in. He committed to paying all the hospital and medical costs as the bills came in, as he’d always done in the past. But he asked that the paperwork required to transfer legal parentage be signed first.

Gil wanted to be paid first. But, still weak, she didn’t have the strength for a fight. So, she turned over the negotiations to a fellow surrogate, who I’ll call Jenny Lee, who had successfully managed two of her own surrogacies, was active on the message board in support of others and had followed Gil’s surrogacy closely. “She was a kick-ass advocate for me,” Gil recalls.

Lee contacted the family, introduced herself and gave very specific instructions for how she wanted things to go down: they were to reimburse for a doctor’s bill “TODAY” by e-transfer, for the seventh month payment “TOMORROW” by e-transfer, and the balance was to be sent to a lawyer, who would hand it over precisely when the paperwork was signed. Bank draft only, she specified; no personal cheques.

“We feel your proposal is fair,” the dad wrote back amicably. But according to Jenny Lee’s emails from the time, the lawyer told the parents that she wouldn’t do that. So, the father reiterated that the surrogate should just sign the papers and the parents would send the money. Gil refused to budge: “No go,” she wrote Lee. “I want an even deal.”

Lee honoured that position, and negotiated hard. A few days later, she posted on the surrogate message board: “I have gotten them to send the bank draft to the lawyer....So [Gil] will get the bank draft first, then sign the papers.” (The lawyer vehemently denies that this ever happened.) Two weeks later, Gil received the bank draft for $17,900 and signed the documents required to give up legal parentage.

*

A central purpose of Canada’s 2004 law, the Assisted Human Reproduction Act, was to protect people such as Gil. Lawmakers feared exploitation of surrogates. But they fixated on one type of exploitation over all others—coercion through money—and they failed to fully anticipate the many other perils faced by people like Gil and the commissioning family in what is inevitably a delicate arrangement.

The law’s architects were primarily concerned that if wombs and gametes were allowed to be traded openly in the marketplace, vulnerable people would be enticed to monetize them. As a result, lawmakers decided that only individuals offering these things for free, out of the goodness of their hearts, could be trusted to be doing it without coercion.

They had in mind, where surrogacy was concerned, mostly sisters or cousins or nieces offering help within their own families. The idea of a stranger being contracted to carry a baby seemed to arouse a certain discomfort, not unlike what people often feel about paid sex work. A pregnancy was too intimate—too sacred—to sell. They couldn’t fathom that a sane woman would grow a child in her uterus only to relinquish it, let alone take money for doing so.

But the reasoning that underpins these ideas comes from a different time in medical and social history. The Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies was launched almost thirty years ago, in 1989, and most surrogacies at the time involved a woman gestating a fetus made from her own egg. Mary Beth Whitehead, a New Jersey surrogate who in 1986 decided to keep the baby, was at the front of everyone’s mind. The discovery that it was even possible for a woman to gestate someone else’s embryo had only been made in 1983 and the practice was not yet widespread.

When Canada’s law actually came into force years later in 2004, after a number of false starts, it still reflected that earlier view—that women would be contracting to give up their own genetic babies for money, and that surrogacies with strangers were morally questionable. Consequently, payment was outlawed, and anyone looking to lure a hapless woman into the baby trade through offers of money could be thrown into prison for up to ten years, fined up to half a million dollars, or both.

The Assisted Human Reproduction Act has been a spectacular failure.

A big part of the reason for that failure is that while the debates dragged on, science advanced rapidly. Increasingly, surrogacies involved babies not genetically related to the surrogate, as with Gil. Many people (though not all) have an easier time accepting contract gestation when there are no genetic ties between the woman carrying the baby and the child itself. During those same years, society had also advanced: parenthood for gay men, for instance, was becoming ever more commonplace and, therefore, so was surrogacy. Eggs and sperm were more readily available. The reality even in 2004, and much more so today, is that many people do accept the idea that a woman can carry a baby for someone else and hand it over to them, without being “unnatural” to start with or psychologically harmed by the very process.

This change in attitude has made prosecuting difficult, especially when, as is often the case, both sides are happy with the arrangement. This was the dilemma faced by the Crown during the one and only prosecution under the Assisted Human Reproduction Act. Leia Picard, now Leia Swanberg, a fertility broker whose business involves bringing together surrogates, egg donors and parents (she is careful about the wording, because taking money for matching is also a criminal offense under the law), was convicted in 2013 of paying surrogates and egg donors outright. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police found that, although Picard’s agency, Canadian Fertility Consulting, had collected envelopes full of receipts, in many instances these envelopes had never been opened, did not add up to the amounts disbursed, and often pertained to expenses not directly related to surrogacy, like car insurance or household purchases. But even as the judge read out the $60,000 fine, he made a point of conceding that her clients appreciated the work that she did.

Ironically, despite its central goal, not only has the law failed to curb the commercial trade in wombs domestically, it has contributed to turning Canada into a magnet for international clients. Several of the country’s top doctors, lawyers and brokers actively solicit international clients at trade fairs and conferences around the world. The fiction of altruism combined with the threat of prosecution has kept surrogacy prices low. Typically, Canadian surrogates earn in the low $20,000s, whereas Americans take home the Canadian dollar equivalent of $40,000 to $50,000. (It’s worth noting that some women really do offer surrogacy without pay.) Add to that the fact that all Canadians (Gil was not one) enjoy publicly funded medical care, even when they go through high-risk pregnancies-for-hire for foreigners, and it’s not hard to see why Canada has become an appealing surrogacy destination.

*

A regulatory regime that really had everyone’s best interests at heart would have committed to studying how surrogacies played out in real life. Had lawmakers made genuine efforts to understand surrogacy, they might have devised a different strategy for managing the risks.

They might have understood that the real dangers were less about coercion to participate and more a matter of how the arrangement was carried out. Gil is clear that the money the couple offered didn’t coerce her into anything—any more than the money she earns at her current job coerces her. Surrogacy, she maintains, was something that she was curious about and wanted to try. Prostitution, on the other hand, was something she had never wanted to be involved in, and when someone once half-seriously suggested she become an escort, she turned the offer down flat, even though, as she points out, the money would have been significantly better than what she got for surrogacy.

What’s undeniable about Gil’s experience is that both parties were comfortable, and remained comfortable throughout, with the central transaction: the couple wanted a baby or babies, and Gil was happy to carry them, for a fee. The fact of one woman gestating babies for another and relinquishing them upon birth never in itself became a point of tension between them. Neither did the fact of money being paid for that service. According to Karen Busby, a law professor at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, who published a systematic review of forty research studies on surrogacy, satisfaction with the arrangement is not uncommon.

Nonetheless, Gil’s surrogacy highlights serious problems. One was that she didn’t know her rights as a patient. Gil had four embryos transferred into her uterus, even though she voiced concern about the prospect of even two. Part of the reason she didn’t know her rights as a patient is that she did not get, and was not required to get, independent legal advice. Some lawyers, Busby among them, think it should be mandatory for surrogates to get this advice.

Another risk to Gil was that the physician who carried out the transfer did not follow professional guidelines on the number of embryos to put in. According to research by Pamela White, a specialist associate lecturer at Kent Law School in the United Kingdom, Canadian fertility doctors are also more likely to transfer more than the recommended number of embryos when the patient is a surrogate, as compared to patients going through IVF for themselves.

White looked at data available through the Canadian Assisted Reproductive Technologies Register, owned by IVF clinic medical directors and which collects, voluntarily, data on assisted reproduction, including number of embryos transferred and whether the woman was acting as a surrogate, and the Better Outcomes Registry and Network. The difference was especially pronounced if, as in Gil’s case, donor eggs had been used. In 2012, for instance, 85 percent of surrogates had two or more embryos transferred, compared to only 57 percent of non-surrogates. If Canadian guidelines had been followed, White calculates, more than 50 percent of gestational surrogates would have had only a single embryo transferred, yet just 15 percent did.

Why aren’t Canadian fertility doctors following their own guidelines? White says her findings raise the issue of whether protections should be in place to limit the risks that surrogates are allowed to take. Surrogates, who undergo medical procedures for the benefit of other people, are patients who deserve extra protection, not diminished protection, says White.

Agreements should not be made that involve the parents trying to tell women what they can eat and how much they can exercise, Ogbogu argues, as these stipulations are unenforceable and thus misleading. “A surrogate cannot agree to anything I cannot force my wife to do,” he says. In other words, a surrogate has every bit as much agency as any other pregnant woman, and commissioning parents should be reminded of that, not led to believe otherwise.

Ironically, one of the things that made Gil’s surrogacy especially precarious was the very federal law that had been designed to protect her. Because at the time no one had been prosecuted for breaking it, people assumed it was okay to do so. It appeared to Gil that the lawyers and doctors were all in on the sham. Like paying in cash to avoid HST, paying a fee and pretending it was expenses had become normal practice.

Yet both sides knew that they were engaged in something murky. They had signed an agreement they knew to be partly fiction. The deceit made it difficult to talk through honestly what was happening, or could happen. While the parents knew, for instance, that they had agreed to pay a fee plus expenses, they were somehow caught off guard when unanticipated expenses arose. Did no one counsel them about what actual expenses could amount to, on top of the fictional ones? Did no one tell them about the chance of multiples being born early, and what that could cost, given their uninsured surrogate?

Allowing fees to masquerade as expenses made the experience much more dangerous for both sides. This sort of fiction continues today.

The agency that was set up as a result of the 2004 law, Assisted Human Reproduction Canada, could have played a key role in alleviating many of these problems. It could have provided clear and accurate information to surrogates and families alike about informed consent, medical rights and the dangers of multiple births. It could have been the central repository for data on assisted reproduction—everything from numbers of surrogates and numbers of embryos transferred, to live births and birth outcomes. (To the extent that any data are collected in this country today, it is voluntary, not very extensive and owned by a group of private fertility doctors. Both the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority have some mandated data-gathering capacity for assisted reproduction.) It could have also spearheaded qualitative research about the relationships between surrogates, would-be families, fertility brokers and society at large, and used it to advise government on policy. A federal agency could also have worked with provinces to resolve issues around legal parentage, vital statistics and even medical standards. Instead, after a few years of blundering, in 2012, the Canadian agency was simply scrapped.

*

After getting the bank draft in hand, Gil thought: “They have the babies. I have the money. It’s done.” But there would be one last chapter in their shared story.

About a week later, Gil received a letter from the provincial government alerting her to the fact that she could apply for child benefits. She imagined how great it would be to collect the money—she had a surrogate friend who did that, with the family’s blessing—but she didn’t want to have any further entanglements. She emailed the family and asked what she should do, and they referred her to their lawyer. It did not occur to Gil that the letter signaled anything more significant.

Further correspondence arrived about two months later, however. This was from the provincial court. At first, Gil didn’t know what it meant. She emailed the parents again: “I am just not really clear...It says the petitioners request was not granted and therefore dismissed. Is this just lawyer speak that all is well?”

In fact, it was a copy of a court judgment informing her that the parents’ effort to make the intended mother the legal mother had failed. Gil, the document said, remained the twins’ legal mother. That meant, according to the document, she not only had authority over the babies, but she also had a duty to provide for them. The ruling also said that since the children were now residing outside the province, her home province had no jurisdiction to resolve the matter. It would have to be dealt with where the children lived.

Gil was angry that neither the family nor their lawyer had informed her about any of this directly. She demanded to know what was going on and what would happen next. The lawyer assured Gil that the parents would try again in their own province and that everyone was working hard to resolve this. “Try to relax,” she wrote.

After all she’d been through, Gil just wanted everything to be settled so she could move on. She also happened to be in the middle of applying for permanent resident status in Canada. She was terrified that appearing to be the mother of two babies—or, worse, a miscreant involved in a reproductive crime—could ruin her bid.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada was asking her to submit not only the babies’ birth certificates, which she had copies of, but photos, which she did not. Reluctantly, she contacted the parents yet again, brusquely explaining the problem, and demanding electronic photos: one headshot and one body shot each, against a white background. She threatened to “exercise [her] parental authority” and come get the photos herself if they didn’t comply.

Luckily, not long after, the surrogacy case was brought before a judge in the parents’ home province. Their lawyer had to present evidence that the mom had always intended to be a legal parent, that Gil had never intended to be one and that only money for expenses had changed hands. Not quite five months after the babies were born, the judge declared that the intended parents were the children’s only legal parents. Gil, who finally became a permanent resident the following year, was scrubbed from the record.

And they all lived happily ever after.

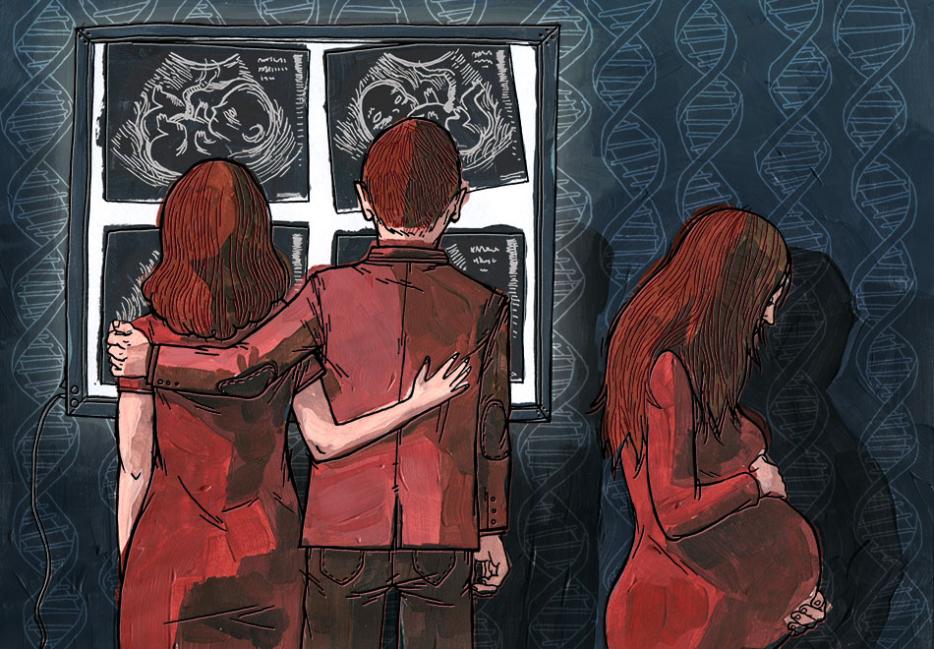

Artwork is not meant to be an accurate representation of any subjects featured in the article. Any likeness similarity in the above illustration is purely coincidental.