Weird Sister is a column about Shakespeare, and marks the first time the author has used her Master's Degree in Shakespearean Studies since its acquisition in 2011.

Long before Wattpad or Twilight or 50 Shades, Margaret Atwood was a fan of fan fiction. So, she says, was any lover of classical literature, whether they realized it or not.

“It’s been going on since ancient Greek times,” she says. “There were a number of different versions of the Odyssey stories. We happen to have the one that was written down and presented to us as Homer’s, but there were a lot of other variants at the time. When Don Quixote was published, people started immediately ripping it off. This is just something that happens with successful fictions.”

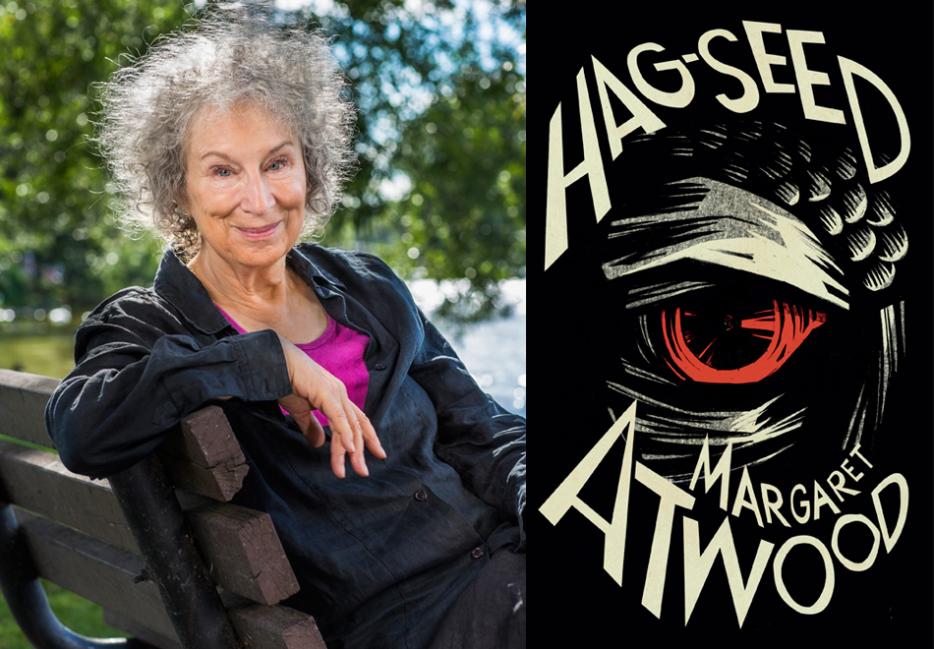

Hag-Seed, Atwood’s newest novel—a re-telling of The Tempest set mostly in a Canadian prison—is a kind of fan fiction, and the joy she takes in the source material is evident. Released this week,it is the fourth title in the Hogarth Shakespeare series, which has best-selling authors crafting novels inspired by the Bard’s thirty-seven extant plays.

Atwood says adaptations like these require both a reverence for and willingness to desecrate their source material, and is quick to point out that Shakespeare himself based many of his plays on preexisting myths or folk stories: “What does fan mean?” she asks. “It’s from the word fanatic, someone with a passionate interest.”

The author herself is interested in Shakespeare to the point that she seems somewhat incredulous when I ask what his appeal is to her, personally. “Oh come on, what a question. His multiplicity, his ability to understand human beings… his theatricality,” she says. “Quite often with Shakespeare you read it on the page and think, this will never work. But with few exceptions the plays are extremely performable.”

*

Hag-Seed occupies itself with this performability, following Felix Philips, the former artistic director of the Stratford-esque Makeshewig Festival as he stages a production of The Tempest at the Fletcher County Correctional Institute. The Tempest is not a play known for its stageability—it opens with a shipwreck and features densely rhetorical speeches, a magically vanishing banquet as well as the shapeshifting and sometimes invisible Ariel—but Felix, we learn, is famous for adventurous reimaginings of Shakespeare’s classics. Casting himself in the lead role and filling in the rest of the cast with an ensemble of convicted felons, Felix both plays the part of Prospero and borrows from his story, using the prison play as an excuse to enact revenge on a duplicitous colleague who ousted him from his festival.

The Tempest is often considered something of a challenge: there’s magic, for one; added to this, the prevalence of songs, special effects, and an overarching moral ambiguity that makes it difficult to know who to root for. In Atwood’s telling, Felix allows the prisoners to rewrite the songs, magic is provided through illegally-procured hallucinogens, and modern technology creates some rudimentary special effects, though the ambiguity remains.

It is precisely this ambiguity that attracted Atwood. “I didn’t think of it as a problem play,” she said. “I thought of it as a play with some unanswered questions. When you go back through various stage productions, they’ve been extremely varied in terms of where they put the emphasis, and the play allows that. People have always edited the play to make it fit the production that they were putting on.”

Prospero, an aged conjurer, closes Act V by retiring the costume, props, and book of incantations that have given him his powers of creation.

The breadth of Atwood’s research is obvious (she includes a lengthy bibliography and a helpful plot summary for the less-researched reader), and results in a pointillistic work full of small, artful nods to its source. Fletcher’s inmates, for instance, are forbidden to use curse words except those found within the play, a conceit Atwood exploits with glee (“Red plague rid thee,” she says, is a favourite), and which peppers the novel with the early modern period’s inventive swears; the minor role “Auspicious Star” in the original morphs cleverly into Estelle, Felix’s ally and a supporter of drama programs in prisons; the Fletcher Institute itself winks at John Fletcher, a playwright with whom Shakespeare collaborated on at least two plays after writing The Tempest.

For her collaboration, Atwood began at the end: “I started with the epilogue, which is one of the most peculiar epilogues in Shakespeare,” she says. “It ends with three words: ‘Set me free,’ spoken by Prospero, who is in effect asking the audience to free him from the play in which he is a character. Get your head around that one! So it’s about prisons, partly, and about how we free ourselves or how we are freed. You know, how do you get out of this place you don’t want to be?”

Imprisonments both literal and metaphorical are frequent themes of Atwood’s, and Hag-Seed focuses on both, presenting literature as a step, if not towards freedom, then towards a redemptive humanity in either case. “Shakespeare rehabilitates in a different way,” Atwood says. “You don’t necessarily get a message of hope at the end of Hamlet, do you? But I think because he understands the multiplicity of human character so well, people can see their own conflicts and their own ambiguities in the characters. […] Everybody in The Tempest either has been imprisoned or is put in prison or is threatened with being imprisoned, in the entire play. Everybody.” Inspired at least in part by Montaigne’s “On Cannibals,” the conditions required for an “ideal commonwealth” are a central concern of the characters in The Tempest. Meditations on justice, punishment, and retribution run through Hag-Seed, although Atwood insists her work does not forward a vision of own her ideal Commonwealth. (What would her utopia include? “Probably more Shakespeare.”)

Hag-Seed also shows the reader something its source material does not: what happens to its characters after Prospero’s epilogue and the end of the play. As elsewhere in the novel, this revelation is performed on textual and meta-textual levels, with the prisoner-actors composing potential afterlives for their characters as a closing assignment in Felix’s program.

*

The Tempest is often mistakenly called Shakespeare’s final play. This bit of false trivia has given the play its reputation as Shakespeare’s farewell to the theatre, with Prospero standing in for the playwright himself. While Shakespeare co-authored at least two plays—The Two Noble Kinsmen and Henry VIII, as well as, possibly, the now-lost Cardenio—after The Tempest’s first staging at Whitehall Palace in 1611, it is easy to see why this reading has been so tempting: Prospero, an aged conjurer, closes Act V by retiring the costume, props, and book of incantations that have given him his powers of creation. Despite his daughter’s new home in Naples, he will retire to Milan, where, he says, “every third thought shall be my grave.”

Hag-Seed, too, explores the idea of an elderly creator considering his next move after a successful adaptation. Though the novel ultimately restores its Prospero to his position within the Makeshewig Theatre Festival, it is a restoration in name only: “He’ll work behind the scenes. He’ll break his staff, he’ll drown his book, because it’s time for the younger people to take over.” The figures of Prospero, Felix, and (maybe) Shakespeare are united through The Tempest in a looking back, a surveying of the art they’ve made. Looking ahead, for them, is bleak, their creative powers apparently fading with their youths.

As for Atwood, the second instalment of her graphic novel series #AngelCatbird is out in February, and she has recently filmed cameos in TV adaptations of Alias Grace (for Netflix) and The Handmaid’s Tale (Hulu). There’s been a series order for The Heart Goes Last, as well. Her website says that after book tour season she’ll be hunkering down to spend time with “all those unpublished poems that have accumulated.” I ask Atwood about her relationship to her own artistic legacy, and she shrugs: “Not dead yet.”