My dad only uses blue pens, the type that come in packs of twelve and have nibs a little too big so that the ink runs together if you don’t write in blocky capitals like he does, especially if the pen has overheated in the afternoon sun. He’d have them in the front pocket of his shirt when we’d scramble out of the car with our gloves and our snacks. Tickets in hand, we’d weave through the crowds into the Rangers’ Ballpark in Arlington that my dad called the Temple and find a spot in the blistering hot stands to watch batting practice.

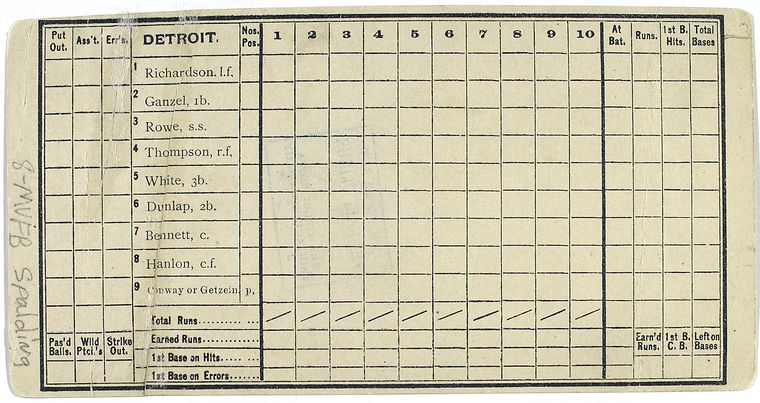

The pen would come out when the screen in center field showed the names of that afternoon’s lineup. Together, we would build the box. He would draw the lines for the innings, write the names on the left hand side of the yellow legal pad, sing the national anthem. The box score, when finished, looked like a cluster of small squares, one per batter per at bat. At the top, inning numbers labeled the vertical columns. The horizontal columns showed each batter’s performance. In the printed versions that come with the five-dollar game program, each box would have a diamond printed to represent the field. But I don’t remember using those. We always drew ours.

Once the box was drawn, we would wait. In the shoeboxes full of keepsakes I’ve moved from apartment to apartment, from where I grew up in Texas to a big coastal city, there are dozens of these yellow pieces of paper. The ink has faded now, but it was smudged to begin with—the running blue lines falling into each other in my uncertain childhood hand.

Baseball is a slow game. Unlike football and basketball, there’s no ticking time bomb to race against. There are no scheduled halves or quarters. A half-inning ends when one team gets three outs. It can take ten minutes and three batters wildly swinging or an hour of base hits and runs scored. The fastest baseball game ever was played in 1919. It took fifty-one minutes. The longest lasted eight and a half hours, in 1984. When you sit down to watch a game, you have to settle in. And the best way to settle in is to score it yourself, to mark every play, every base advancement, every wild pitch.

Besides biting my nails, there is no habit I’ve kept in my life for as long as the box score. Once, when I was seven, a small boy about my age sat behind my family in the outfield. It was a brutal day, as most summer games are in the Texas heat, and around the fourth inning he started to whine. He was too hot, there wasn’t enough food, the game was too boring. My dad leaned over to me and jokingly muttered “baseball is dull to dull minds,” before tapping the yellow pad with his pen. “Pay attention.”

In the most basic version of a box score, every player’s turn at the plate is marked inside a square next to their name. Every defensive position is assigned a number, and every potential play assigned a letter. Let’s say the hitter pops the ball up high into the sky, and after it plummets back to earth the second baseman catches it. Our hitter is out. F is for fly out and the second baseman is always number 4. So inside the box, we write F-4. If he strikes out, we put a K in his box. If he strikes out without swinging his bat, we draw the K backwards. If a box score is kept fastidiously, it can tell you what happened in every single at-bat of a game.

In practice, everyone keeps a box score differently, but there’s always a method to the madness. Some people print out mock scorecards to write on top of. Some people use the ones that come with their programs. Some people, like my dad, just draw the lines themselves. L. L. Bean (yes, that one) developed his own format for keeping score. My dad colors in the inside of his diamond whenever a player scores a run. Somewhere along the line, I stopped doing this and started circling the bases a player reached. For any given game, our scorecards would say the same thing in different ways.

*

The box score was invented by Henry Chadwick, a British man who fell in love with baseball as a sportswriter for The New York Clipper. He ran the first box score in the paper in 1859. There was limited photography in 1859, certainly no televisions to watch the games on, and definitely no gifs. If a fan wanted to know what happened in the game, all they had was the score printed in the paper.

Baseball is a game with holiness in its bones. It’s traditional, and in that tradition grows superstition.

But the box score is more than a way to find out what happened during a game. To keep a box score is to become a participant in a century-old art form. While the goal of a baseball game is simple—win by scoring more runs than your opponent—the drama and the skill of the game are often more subtle than other team sports. Sure, there are homeruns and the occasional jaw-dropping outfield catch, but there are 162 games in a baseball season. Highlight-reel plays alone won’t get you to the playoffs; consistently mastering the little things—the double plays, the routine grounders, the perfectly placed bunts—makes a championship team.

It’s hard to enjoy baseball if you don’t know what you’re looking for. And the box score teaches you how to do just that—to look. Every pitch becomes important. Every play becomes yours. Each club has an “official scorekeeper” who decides if a play is a hit or an error when the third baseman kicks the ball, but you don’t have to listen to him. The box score is yours from the minute you write down the team names.

*

Baseball is a game with holiness in its bones. It’s traditional, and in that tradition grows superstition. There’s reverence in keeping a box score that asks you to take this game seriously, to appreciate the movement of the ball and the athleticism of the players. And it’s an art practiced and loved by women just as often as men. In seats in stadiums around the country, little old ladies color in squares in whatever way they think is best. At a Nationals’ game I attended in July, I watched as an usher escorted two old women down the stairs to their seats. Holding their elbows, he helped them to their folding chairs and, once sitting, the one nearest the aisle dug through her bag to pull out a spiral-bound book of box scores. Throughout the game, they kept the score together, passing the pages back and forth between them each inning, shaking their heads when they disagreed on how to mark something.

But, like any place where women exist in male-dominated spaces, sexism runs rampant. At one game I attended with my dad during high school, a group of men behind me leaned forward over the seat making comments about how hot it was that a girl could know the game with the intimacy I did, as if the keeping of a box score wasn’t for my own enjoyment of the game but for theirs. “Fellas, she’s fifteen,” my dad threw over his shoulder, and they backed off.

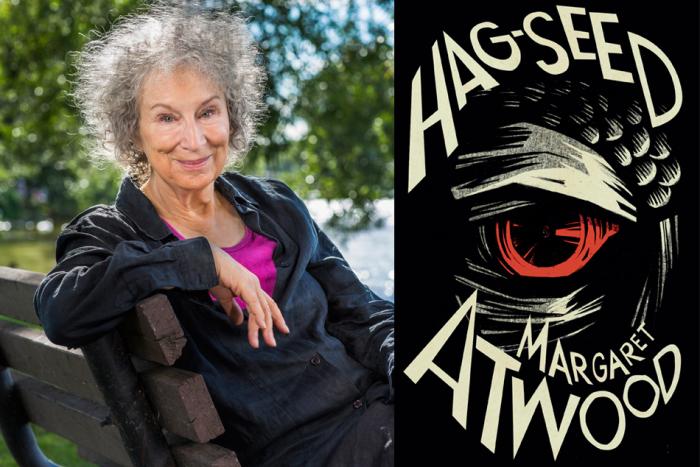

Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Archives.

For the most part, though, there’s community among the box score keepers. Baseball has the oldest viewers of any sport: fifty percent are over the age of fifty-five. Enrollment in little league baseball has dropped rapidly in the last ten years. Though revenue is at an all-time high, Rob Manfred, the commissioner of Major League Baseball told the Washington Post in 2015 that baseball struggles to hook the younger generation. I rarely see kids keeping score at the Washington Nationals games I attend now, but maybe kids never really kept score. I remember people asking how old I was, in awe when they saw me keeping score as a child.

Like baseball’s graying fan base, the box score is dying out steadily. They rarely make the paper anymore. Like baseball, the box score is a slow art, one that asks you to watch carefully what’s happening in front of you and tune out a world whose distractions seem to conspire against just that.

The last time I kept score at a Nationals game, there was a man a few seats over who kept his in dark black ink. Eventually we got to talking about the pitcher's hanging curveball and Bryce Harper's arm. Near the end of the game, I asked him about a mark on his board I'd never seen before, a "WW" that occupied several squares.

"Oh," he told me, "that's the saddest mark of all. It means I wasn't watching."